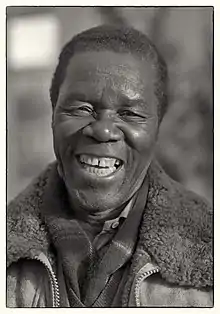

Joram Mariga

Joram Mariga has been called (and believed himself to be) the “Father of Zimbabwean Sculpture” because of his influence on the local artistic community starting in the 1950s and continuing until his death in 2000. The sculptural movement of which he was part is usually referred to as “Shona sculpture”, although some of its recognised members are not ethnically Shona.

Joram Mariga | |

|---|---|

Joram Mariga | |

| Born | Joram Mariga 1927 |

| Died | December 2000 Bonda Mission Hospital, Zimbabwe |

| Nationality | Zimbabwean |

| Education | Informal |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Movement | Shona sculpture |

| Awards | Highly Commended, Zimbabwe Heritage Exhibition, 1989 |

Joram Mariga died in December 2000 soon after arrival at Bonda Mission Hospital, following a car accident.[1]

Early life and education

Born near Chinhoyi, (formerly called Sinoia) in what in 1927 was Southern Rhodesia, Joram Mariga was ethnically Shona and spoke Zezuru, a local dialect. He was the son of a sangoma, and both of his parents were artistic. His father and elder brothers (Copper and Douglas) were expert woodcarvers, while his mother made pottery. All of them sold their work to members of the community.[2] Aged eight or nine, he started to carve wood, and at school he joined wood working classes. As a herdboy, his first subject-matter was cattle. Joram attended secondary school in Goromonzi and studied at the Waddilove Institute. He qualified as an agriculturist and was employed by Agritex.[3] His career as a sculptor in stone began in 1957 when he discovered long sought-after caches of green Inyanga (Moon) soapstone while leading a roadbuilding crew in eastern Rhodesia. Unaware of the importance of his find, he started to use it to produce utensils and small figures.[4] He also began teaching members of his road building crew to carve the stone using woodcarving tools.

Development of Zimbabwean stone sculpture

Central Zimbabwe contains the "Great Dyke" – a source of serpentine rocks of many types including a hard variety locally called springstone. An early pre-colonial culture of Shona peoples settled the high plateau around 900 AD and "Great Zimbabwe", which dates from about 1250–1450 AD, was a stone-walled town showing evidence in its archaeology of skilled stone working. The walls were made of a local granite and no mortar was used in their construction.[5] When excavated, six soapstone birds and a soapstone bowl were found in the eastern enclosure of the monument, so art forms in soapstone were part of that early culture. However, stone carving as art had no direct lineage to the present day and it was only in 1954 that its modern renaissance began. This was when Frank McEwen became advisor to the new Rhodes National Gallery to be built in Harare and from 1955 to 1973 was its founding director (it opened in 1957). The Gallery had been intended to bring non-African art to Harare but when McEwen created the Workshop School to encourage new work in painting and sculpture, the local community of artists re-discovered latent talents for stone sculpture. Joram was introduced to McEwen and soon they were in regular contact: Mariga exhibited at the Gallery extensively from 1962 but always worked on his own in his spare time and later at his studio in Greendale, Harare.[1]

Later, McEwen would remember him thus:

The sculptural expansion developed in only 34 years. To give a true example, among others arriving from different parts of the country came Joram Mariga. He was not the first to come to the workshop, but one of the best...He brought me a little milk jug carved in soft stone. I realised this was an English milk jug for an Englishman who loved his tea! I asked if he could make a head. The head came, made also for an Englishman, in the style of airport art as acquired by tourists. "If you made a figure for your own family or your ancestors?" I asked. "Oh, that would be different." The figure came, this time of pure African concept - the enlarged head, seat of the spirit, a frontal static pose, a visage staring into eternity with formally posed arms and clenched fists. It was pre-Columbian in nature, as if a spirit image applied to stone could create similar results in spite of a difference of race, place and time.[6]

The milk jug and two of Joram's early stone sculptures were part of McEwen's bequest to the British Museum.[7][8]

After 1962 Mariga abandoned the use of soft soapstone and began to use larger, harder blocks of serpentine that he found in the course of his work.[9] He also began working with new tools. As his technique developed, he taught numerous others what he had discovered. These other artists included his former roadbuilders, as well as artists such as Joseph Ndandarika who were sent to train with him by McEwen.[10]

By 1967, Joram was arguably the leading Zimbabwean sculptor, and his compatriots followed working in newer stones such as serpentine and springstone that he pioneered. One of his sculptures was depicted on a Rhodesian postage stamp, part of a set issued on 12 July 1967 to commemorate the Tenth Anniversary of the opening of the Rhodes National Gallery. Other stamps in the set illustrated works by Auguste Rodin, Roberto Crippa and M. Tossini. In 1966, the first Tengenenge serpentine springstone deposit was discovered by Crispin Chakanyuka, a former apprentice of Mariga's who was working for Tom Blomefield.

1969 was an important year for the new sculpture movement, because it was the time when McEwen took a group of works to the Museum of Modern Art in New York and elsewhere in the US, to critical acclaim. It was also the year that his wife Mary (née McFadden) established Vukutu, a sculptural farm near Inyanga, which the artists could work. Mariga found the location for the McEwens and was promised by them that he would lead the artistic commune. After he was suspected of harboring ZANU insurgents and transferred to a distant region, McEwen refused to have Mariga at Vukutu and installed Sylvester Mubayi as the leader.[11]

The list of names of Vukutu sculptors who would become internationally well-known grew to include Bernard Matemera, Sylvester Mubayi, Henry Mukarobgwa, Thomas Mukarobgwa, Nicholas Mukomberanwa, Henry Munyaradzi, Joseph Ndandarika, Bernard Takawira and his brother John: together with Joram Mariga himself they formed the “first generation” of new Shona sculptors. All contributed work to an exhibition called Arte de Vukutu shown in 1971 at the Musée National d'Art Moderne and in 1972 at the Musée Rodin, arranged by McEwen, who had lived and worked in Paris prior to his appointment in Harare. Mariga was a member of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe's Board of Trustees from 1982 till 1993.[1]

He participated in the 1989 Pachipamwe II Workshop held at Cyrene Mission outside Bulawayo, Zimbabwe alongside sculptors including Adam Madebe, Bernard Matemera, Bill Ainslie, Voti Thebe and Sokari Douglas Camp.[12]

While many of these artists went on to successful careers, Mariga's career suffered after his transfer to Chipinga. In this region he quickly ran out of stone, and found nothing available locally to sculpt with. Depressed after his betrayal by the McEwens, his artistic output largely consisted of elaborate woodcarvings made for his own household. He would not resume stone carving until a triumphal return in the late 1980s.[13]

Later life and exhibitions

Mariga was married four times. With his first wife, Doreen, he had a daughter, Mary. His second wife was Philipa, the mother of Owen, Richard and Robin. Anne was his third wife who was the mother of Walter, Daniel, Aaron and Jay. In 1976 Joram married Maud but they had no children.[1]

As Jonathan Zilberg has pointed out,[14][15] the nascent Shona sculpture movement was slow to gain momentum, partly because of the generally negative attitude in the 1960s and 1970s of local Europeans toward Frank McEwen and the sculptors he encouraged, in what was still a country ruled by a white minority government whose Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965 was seen by the United Nations as racist. According to Aeneas Chigwedere, a Zimbabwean historian and politician, there were at that time very few educated black Africans who saw any value in what Joram Mariga and others were doing and they did not buy art that reflected their own culture, owing to indoctrination by the white ruling class. The importance of individual artists and their patrons in drawing the new sculpture movement to the attention of a worldwide audience has been discussed by Pat Pearce (a sculptor who lived in Nyanga and who first introduced Mariga to McEwen) [16] and by Sidney Littlefield Kasfir.[17]

Much of Mariga's work includes themes drawn from the culture of the Shona people, and incorporates subject matter taken from nature. He believed that "One should avoid realism, create a large place for the brain and large eyes, because sculptures are beings who must be able to think and see for themselves for eternity".[18] Many of his sculptures were carved in springstone but Joram also used more unusual stones such as leopard rock (a serpentine with green and yellow inclusions), and lepidolite, in the lilac purple colour available to him. One of the lepidolite sculptures, “Spirit of Zimbabwe” (1989) was displayed at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in 1990 and the catalogue for the exhibition [4] includes both a picture (p. 28) and extracts from an interview with Mariga (p. 42-43) when he worked there from 22 to 30 July 1990. It also includes (p. 44) a picture of his large work “Communicating with the Earth Spirit” (1990). In 1989, two of Mariga's works were Highly Commended in the Zimbabwe Heritage Exhibition at the Natitional Gallery, where his solo exhibition "Whispering the Gospel of Stone" had taken place. One of these, called "Calabash Man", is illustrated in Celia Winter-Irving's book on Stone Sculpture (see Further Reading) which also contains much additional material on Joram in his artistic context.

The catalogue “Chapungu: Culture and Legend – A Culture in Stone” for the exhibition at Kew Gardens in 2000 depicts Joram's sculpture “Chief Chirorodziwa” (Lepidolite, 1991) on p. 100-101.[19]

Besides being a sculptor, Mariga was a teacher, counting among his students John and Bernard Takawira and Crispen Chakanyuka, (all his nephews), Bernard Manyadure, Kingsley Sambo, and Moses Masaya. He would also take students from further afield, generally while travelling.[1]

In 2000, Mariga gave a filmed interview with Jonathan Zilberg, in which he gave an account of his life and work.[20]

Selected solo or group exhibitions

- 1962 New African Talent, National Gallery of Zimbabwe

- 1963 New Art from Rhodesia, Commonwealth Arts Festival, Royal Festival Hall, London

- 1972 Shona sculptures of Rhodesia, ICA Gallery, London

- 1989 Whispering the Gospel of Sculpture, National Gallery of Zimbabwe

- 1989 Zimbabwe op de Berg, Foundation Beelden op de Berg, Wageningen, The Netherlands

- 1990 Zimbabwe Heritage (National Gallery of Zimbabwe), Auckland, New Zealand

- 1990 Contemporary Stone Carving from Zimbabwe, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, UK

- 1991 The Thirty Five Years, Chapungu Sculpture Park, Zimbabwe

- 1993 Talking Stones II, The Contemporary Fine Art Gallery Eton, Berkshire, UK

- 1994 Joram Mariga: An Exhibition of Recent Sculpture, Chapungu Sculpture Park, Zimbabwe [21]

- 2000 Chapungu: Custom and Legend – A Culture in Stone, Kew Gardens, UK

- 2001 Tengenenge Art, Celia Winter-Irving, World Art Foundation, The Netherlands

Further reading

- Winter-Irving C. “Stone Sculpture in Zimbabwe”, Roblaw Publishers (A division of Modus Publications Pvt. Ltd), 1991, ISBN 0-908309-14-7 (Paperback) ISBN 0-908309-11-2 (Cloth bound)

- Winter-Irving C. “Pieces of Time: An anthology of articles on Zimbabwe’s stone sculpture published in The Herald and Zimbabwe Mirror 1999-2000”. Mambo Press, Zimbabwe, 2004, ISBN 0-86922-781-5

References

- "Biography from National Gallery of Zimbabwe". Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- Elizabeth Morton, "Frank McEwen and Joram Mariga: Patron and Artist in the Rhodesian Workshop School Setting." In S. Kasfir and T. Forster, eds., African Art and Agency in the Workshop (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013), 278.

- Winter-Irving C. "Stone Sculpture in Zimbabwe" p95-97, Roblaw Publishers (A division of Modus Publications Pvt. Ltd), 1991, ISBN 0-908309-14-7 (Paperback)

- Contemporary Stone Carving from Zimbabwe, 1990, ISBN 1-871480-04-3

- Needham D.E., Mashingaidze E.K, Bhebe N. 1984 "From Iron Age to Independence, A History of Central Africa", p17. Longman, England. ISBN 0-582-65111-5

- "Quote from africansuccess.org". Archived from the original on 2010-11-19. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- "McEwen Collection". britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- Zilberg, J. (2006). "The Frank McEwen Collection of Shona Sculpture in the British Museum" (PDF). National Gallery of Zimbabwe. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- Morton, "Frank McEwen and Joram Mariga," 280.

- Morton, "Frank McEwen and Joram Mariga," 280-2.

- Morton, "Frank McEwen and Joram Mariga," 285-8.

- Elsbeth, Court. "Pachipamwe II: The Avant Garde in Africa?". African Arts. 25 (1). ISSN 0001-9933.

- Morton, "Frank McEwen and Joram Mariga," 288.

- Zilberg, J. 1995. "Shona Sculpture's Struggle for Authenticity and Value," Museum Anthropology 19, 1:3-24

- Zilberg, J. 2001. "The Radical Within the Museum: Frank McEwen and the Rhodesian Philistines," in Kunst aus Zimbabwe -- Kunst in Zimbabwe, eds. Till Forster, Marina Von Assel. Ein Ausstellungsprojekt. Iwalewa-Haus. Bayreuth: Afrikazentrum der Universitat Bayreuth

- Pearce P. 1993. "The Myth of Shona Sculpture," Zambezia 20, 2:85-107

- Kasfir, S. L. 2007. "African Art and the Colonial Encounter: Inventing a Global Commodity". Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-21922-1

- Sultan, O. “Life in Stone: Zimbabwean Sculpture – Birth of a Contemporary Art Form”, 1994, ISBN 978-1-77909-023-2

- Catalogue published by Chapungu Sculpture Park, 2000, 136pp printed in full colour, with photographs by Jerry Hardman-Jones and text by Roy Guthrie (no ISBN)

- Zilberg, Jonathan (2001). "Joram Mariga. (film/video)". African Arts. 34 (3): 80. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- Mawdsley J. 1994. "Joram Mariga", Catalogue published by Chapungu Sculpture Park (no ISBN)

External links

Media related to Joram Mariga at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Joram Mariga at Wikimedia Commons