Napster

Napster was a peer-to-peer file sharing application that originally launched on June 1, 1999 with an emphasis on digital audio file distribution. Audio songs shared on the service were typically encoded in the MP3 format. It was founded by Shawn Fanning, Sean Parker. As the software became popular, the company ran into legal difficulties over copyright infringement. It ceased operations in 2001 after losing a wave of lawsuits and filed for bankruptcy in June 2002.

Variation of the Napster Logo | |

.png.webp) Napster running under Mac OS 9 in March 2001. | |

| Developer(s) | |

|---|---|

| Initial release | June 1, 1999 |

| Final release | September 3, 2002

|

| Operating system | cross-platform |

| Available in | Multilingual |

| Type | Media player |

| Website | www |

Later, more decentralized projects followed Napster's P2P file-sharing example, such as Gnutella, Freenet, FastTrack, and Soulseek. Some services and software, like AudioGalaxy, LimeWire, Scour, Kazaa / Grokster, Madster, and eDonkey2000, were also brought down or changed due to copyright issues.

Napster's assets were eventually acquired by Roxio, and it re-emerged as an online music store. Best Buy later purchased the service and merged it with its Rhapsody service on December 1, 2011,[1] rebranding back to Napster.

Origin

Napster was founded by Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker.[2] Initially, Napster was envisioned by Fanning as an independent peer-to-peer file sharing service. The service operated between June 1999 and July 2001.[3] Its technology enabled people to easily share their MP3 files with other participants.[4] Although the original service was shut down by court order, the Napster brand survived after the company's assets were liquidated and purchased by other companies through bankruptcy proceedings.[5]

History

Although there were already networks that facilitated the distribution of files across the Internet, such as IRC, Hotline, and Usenet, Napster specialized in MP3 files of music and a user-friendly interface. At its peak, the Napster service had about 80 million registered users.[6] Napster made it relatively easy for music enthusiasts to download copies of songs that were otherwise difficult to obtain, such as older songs, unreleased recordings, studio recordings, and songs from concert bootleg recordings. Napster paved the way for streaming media services and transformed music into a public good for a brief time.

High-speed networks in college dormitories became overloaded, with as much as 61% of external network traffic consisting of MP3 file transfers.[7] Many colleges blocked its use for this reason,[8] even before concerns about liability for facilitating copyright violations on campus.

Macintosh version

The service and software program began as Windows-only. However, in 2000, Black Hole Media wrote a Macintosh client called Macster. Macster was later bought by Napster and designated the official Mac Napster client ("Napster for the Mac"), at which point the Macster name was discontinued.[9] Even before the acquisition of Macster, the Macintosh community had a variety of independently developed Napster clients. The most notable was the open source client called MacStar, released by Squirrel Software in early 2000, and Rapster, released by Overcaster Family in Brazil.[10] The release of MacStar's source code paved the way for third-party Napster clients across all computing platforms, giving users advertisement-free music distribution options.

Legal challenges

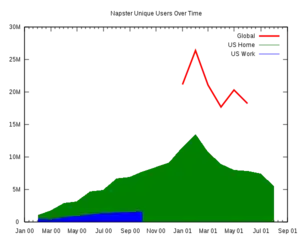

Heavy metal band Metallica discovered a demo of their song "I Disappear" had been circulating across the network before it was released. This led to it being played on several radio stations across the United States, which alerted Metallica to the fact that their entire back catalogue of studio material was also available. On March 13, 2000, they filed a lawsuit against Napster. A month later, rapper and producer Dr. Dre, who shared a litigator and legal firm with Metallica, filed a similar lawsuit after Napster refused his written request to remove his works from its service. Separately, Metallica and Dr. Dre later delivered to Napster thousands of usernames of people who they believed were pirating their songs. In March 2001, Napster settled both suits, after being shut down by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in a separate lawsuit from several major record labels (see below).[11] In 2000, Madonna's single "Music" was leaked out onto the web and Napster prior to its commercial release, causing widespread media coverage.[12] Verified Napster use peaked with 26.4 million users worldwide in February 2001.[13]

In 2000, the American musical recording company A&M Records along with several other recording companies, through the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), sued Napster (A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc.) on grounds of contributory and vicarious copyright infringement under the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA).[14] Napster was faced with the following allegations from the music industry:

- That its users were directly violating the plaintiffs' copyrights.

- That Napster was responsible for contributory infringement of the plaintiff's copyrights.

- That Napster was responsible for the vicarious infringement of the plaintiff's copyrights.

Napster lost the case in the District Court but then appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Although it was clear that Napster could have commercially significant non-infringing uses, the Ninth Circuit upheld the District Court's decision. Immediately after, the District Court commanded Napster to keep track of the activities of its network and to restrict access to infringing material when informed of that material's location. Napster wasn't able to comply and thus had to close down its service in July 2001. In 2002, Napster announced that it had filed for bankruptcy and sold its assets to a third party.[15] In a 2018 Rolling Stone article, Kirk Hammett of Metallica upheld the band's opinion that suing Napster was the "right" thing to do.[16]

Promotional power

Along with the accusations that Napster was hurting the sales of the record industry, some felt just the opposite, that file trading on Napster stimulated, rather than hurt, sales. Some evidence may have come in July 2000 when tracks from English rock band Radiohead's album Kid A found their way to Napster three months before the album's release. Unlike Madonna, Dr. Dre, or Metallica, Radiohead had never hit the top 20 in the US. Furthermore, Kid A was an album without any singles released, and received relatively little radio airplay. By the time of the album's release, the album was estimated to have been downloaded for free by millions of people worldwide, and in October 2000 Kid A captured the number one spot on the Billboard 200 sales chart in its debut week. According to Richard Menta of MP3 Newswire,[17] the effect of Napster in this instance was isolated from other elements that could be credited for driving sales, and the album's unexpected success suggested that Napster was a good promotional tool for music.

Since 2000, many musical artists, particularly those not signed to major labels and without access to traditional mass media outlets such as radio and television, have said that Napster and successive Internet file-sharing networks have helped get their music heard, spread word of mouth, and may have improved their sales in the long term. One such musician to publicly defend Napster as a promotional tool for independent artists was DJ Xealot, who became directly involved in the 2000 A&M Records Lawsuit.[18] Chuck D from Public Enemy also came out and publicly supported Napster.[19]

Lawsuit

Napster's facilitation of the transfer of copyrighted material raised the ire of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), which almost immediately—on December 6, 1999—filed a lawsuit against the popular service.[20] The service would only get bigger as the trial, meant to shut down Napster, also gave it a great deal of publicity. Soon millions of users, many of whom were college students, flocked to it. After a failed appeal to the Ninth Circuit Court, an injunction was issued on March 5, 2001 ordering Napster to prevent the trading of copyrighted music on its network.[21]

Lawrence Lessig[22] claimed, however, that this decision made little sense from the perspective of copyright protection: "When Napster told the district court that it had developed a technology to block the transfer of 99.4 percent of identified infringing material, the district court told counsel for Napster 99.4 percent was not good enough. Napster had to push the infringements 'down to zero.' If 99.4 percent is not good enough," Lessig concluded, "then this is a war on file-sharing technologies, not a war on copyright infringement."

Shutdown

On July 11, 2001, Napster shut down its entire network to comply with the injunction. On September 24, 2001, the case was partially settled. Napster agreed to pay music creators and copyright owners a $26 million settlement for past, unauthorized uses of music, and as an advance against future licensing royalties of $10 million. To pay those fees, Napster attempted to convert its free service into a subscription system, and thus traffic to Napster was reduced. A prototype solution was tested in 2002: the Napster 3.0 Alpha, using the ".nap" secure file format from PlayMedia Systems[23] and audio fingerprinting technology licensed from Relatable. Napster 3.0 was, according to many former Napster employees, ready to deploy, but it had significant trouble obtaining licenses to distribute major-label music. On May 17, 2002, Napster announced that its assets would be acquired by German media firm Bertelsmann for $85 million to transform Napster into an online music subscription service. The two companies had been collaborating since the middle of 2000[24] where Bertelsmann became the first major label to drop its copyright lawsuit against Napster.[25] Pursuant to the terms of the acquisition agreement, on June 3 Napster filed for Chapter 11 protection under United States bankruptcy laws. On September 3, 2002, an American bankruptcy judge blocked the sale to Bertelsmann and forced Napster to liquidate its assets.[5]

Reuse of name

Napster's brand and logos were acquired at a bankruptcy auction by Roxio which used them to re-brand the Pressplay music service as Napster 2.0. In September 2008, Napster was purchased by US electronics retailer Best Buy for the US $121 million.[26] On December 1, 2011, pursuant to a deal with Best Buy, Napster merged with Rhapsody, with Best Buy receiving a minority stake in Rhapsody.[27] On July 14, 2016, Rhapsody phased out the Rhapsody brand in favor of Napster and has since branded its service internationally as Napster[28] and expanded toward other markets by providing music on-demand as a service to other brands[29] like the iHeartRadio app and their All Access music subscription service that provides subscribers with an on-demand music experience as well as premium radio.[30]

On August 25, 2020, Napster was sold to virtual reality concerts company MelodyVR.[31]

On May 10, 2022, Napster was sold to Hivemind and Algorand. The investor consortium also includes ATC Management, BH Digital, G20 Ventures, SkyBridge, RSE Ventures, Arrington Capital, Borderless Capital, and others.[32][33]

Media

- There have been several books that document the experiences of people working at Napster, including:

- The 2003 film The Italian Job features Napster co-founder Shawn Fanning as a cameo of himself. This gave credence to one of the characters fictional back-story as the original "Napster".[37]

- The 2010 film The Social Network features Napster co-founder Sean Parker (played by Justin Timberlake) in the rise of the popular website Facebook.[38]

- The 2013 film Downloaded is a documentary about sharing media on the Internet and includes the history of Napster.

Further reading

- Carlsson, Bengt; Gustavsson, Rune (2001). "The Rise and Fall of Napster – An Evolutionary Approach". Proceedings of the 6th International Computer Science Conference on Active Media Technology.

- Giesler, Markus; Pohlmann, Mali (2003). "The Social Form of Napster: Cultivating the Paradox of Consumer Emancipation". Advances in Consumer Research.

- Giesler, Markus; Pohlmann, Mali (2003). "The Anthropology of File Sharing: Consuming Napster as a Gift". Advances in Consumer Research.

- Giesler, Markus (2006). "Consumer Gift Systems". Journal of Consumer Research. 33 (2): 283–290. doi:10.1086/506309. S2CID 144952559.

- Green, Matthew (2002). "Napster Opens Pandora's Box: Examining How File-Sharing Services Threaten the Enforcement of Copyright on the Internet". Ohio State Law Journal. 63: 799.

- InsightExpress. 2000. Napster and its Users Not violating Copyright Infringement Laws, According to a Survey of the Online Community.

- Ku, Raymond Shih Ray (2001). "The Creative Destruction of Copyright: Napster and the New Economics of Digital Technology". University of Chicago Law Review. doi:10.2139/ssrn.266964. SSRN 266964.

- McCourt, Tom; Burkart, Patrick (2003). "When Creators, Corporations and Consumers Collide: Napster and the Development of On-line Music Distribution". Media, Culture & Society. 25 (3): 333–350. doi:10.1177/0163443703025003003. S2CID 153739320.

- Orbach, Barak (2008). "Indirect Free Riding on the Wheels of Commerce: Dual-Use Technologies and Copyright Liability". Emory Law Journal. 57: 409–461. SSRN 965720.

- Abramson, Bruce (2005). Digital Phoenix; Why the Information Economy Collapsed and How it Will Rise Again. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-51196-4.

- Judge criticises both parties in Napster case

- "The File Sharing Movement" in Jack Goldsmith and Tim Wu, Who Controls the Internet: Illusions of a Borderless World Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 105–125. ISBN 978-0-19-515266-1

References

- Sisario, Ben (2011-10-03). "Rhapsody to Acquire Napster in Deal With Best Buy". Mediadecoder.blogs.nytimes.com. United States. Archived from the original on 2013-04-27. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- Name inspired by Shawn's high school nickname "Nappy" for his signature Afro.

- Pollack, Neal (December 27, 2010). "Spotify Is the Coolest Music Service You Can't Use". Wired. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2019.

- Simon, Dan. Internet pioneer Sean Parker: 'I'm blazing a new path' Archived May 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. CNN. September 27, 2011.

- Menn, Joseph (2003). All the Rave: The Rise and Fall of Shawn Fanning's Napster. Crown Business. ISBN 978-0-609-61093-0.

- Schonfeld, Erick. Shawn Fanning And Sean Parker Talk About Airtime And "Smashing People Together" Archived 2017-07-08 at the Wayback Machine. TechCrunch. October 6, 2011.

- Rosen, Ellen (May 26, 2005). "Student's Start-Up Draws Attention and $13 Million". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2005. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- Bradshaw, Tim. Spotify-MOG battle heats up Archived 2012-10-18 at the Wayback Machine. Financial Times. February 28, 2010.

- Emerson, Ramona. Sean Parker At Web 2.0 Summit Defends 'Creepy' Facebook Archived 2016-03-06 at the Wayback Machine. The Huffington Post. October 18, 2011.

- Kirkpatrick, David (October 2010). "With a Little Help From His Friends". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- "Napster's High and Low Notes". Businessweek. August 14, 2000. Archived from the original on 2019-12-07. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

-

- Giesler, Markus (2006). "Consumer Gift Systems". Journal of Consumer Research. 33 (2): 283–290. doi:10.1086/506309. S2CID 144952559.

- Evangelista, Benny (September 4, 2002). "Napster runs out of lives – judge rules against sale". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- Gowan, Michael (2002-05-18). "Requiem for Napster". Pcworld.com. Archived from the original on 2014-04-26. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- Fusco, Patricia (March 13, 2000). "The Napster Nightmare". ISP-Planet. Archived from the original on 2011-10-19.

- Anderson, Kevin (September 26, 2000). "Napster expelled by universities". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2007-10-21.

- "Official Napster Client For Mac OS, OS X -- The Mac Observer". macobserver.com. Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- Moore, Charles W. "Eight MP3 Players For The Macintosh". Applelinks. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- Giesler, Markus (2008). "Conflict and Compromise: Drama in Marketplace Evolution" (PDF). Journal of Consumer Research. 34 (6): 739–753. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.564.7146. doi:10.1086/522098. S2CID 145796529. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-24. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- Borland, John (June 1, 2000). "Unreleased Madonna Single Slips On To Net". CNET News.com. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012.

- "Global Napster Usage Plummets, But new File-Sharing Alternatives Gaining Ground, Reports Jupiter Media Metrix" (Press release). comScore. 2001-07-20. Archived from the original on 2008-04-13. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- 17 U.S.C. A&M Records. Inc. v. Napster. Inc. 114 F. Supp. 2d 896 (N. D. Cal. 2000).

- .A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc., 239 F.3d 1004 (9th Cir. 2001). For a summary and analysis, see Guy Douglas, Copyright and Peer-To-Peer Music File Sharing: The Napster Case and the Argument Against Legislative Reform Archived 2010-07-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "Metallica's Kirk Hammett: 'We're Still Right' About Suing Napster". Rolling Stone. 2018-05-14. Archived from the original on 2019-10-16. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Menta, Richard (October 28, 2000). "Did Napster Take Radiohead's New Album to Number 1?". MP3 Newswire. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2005.

- "Case Nos. C 99-5183 and C 00-0074 MHP (ADR)" (PDF). FindLaw.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 14, 2006. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- "Rapper Chuck D throws weight behind Napster". Cnet News. May 1, 2000. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

-

- A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc., 114 F. Supp. 2d 896 (N.D. Cal. 2000) Archived 2019-12-04 at the Wayback Machine, aff'd in part, rev'd in part, 239 F.3d 1004 (9th Cir. 2001)

- Menta, Richard (December 9, 1999). "RIAA Sues Music Startup Napster for $20 Billion". MP3 Newswire. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2005.

- 2001 US Dist. LEXIS 2186 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 5, 2001), aff’d, 284 F. 3d 1091 (9th Cir. 2002).

- Lessig, Lawrence (2004). Free Culture: The Nature and Future of Creativity. Penguin. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-0-14-303465-0.

- "Napster to ditch MP3 for proprietary format". theregister.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2017-08-10.

- "Bertelsmann to buy Napster for a song". CNET. Archived from the original on 2016-03-10. Retrieved 2016-02-29.

- Teather, David (2000-11-01). "Napster wins a new friend". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-02-29.

- Skillings (September 15, 2008). "Best Buy nabs Napster for $121 million". cnet.com. CNET. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- "Today is Napster's last day of existence". CNN. November 30, 2011. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- "We Are Napster". Napster Team. July 14, 2016. Archived from the original on July 17, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- "Services | Napster". Napster. Archived from the original on 2018-03-27. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- "Press Releases". www.iheartmedia.com. Archived from the original on 2018-03-27. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- "Napster Sold to Virtual Reality Concert App MelodyVR for $70 Million". Billboard. 2020-08-25. Archived from the original on 2020-08-26. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- "Hivemind and Algorand today announced the acquisition of Napster, to once again revolutionize the music industry by bringing blockchain and Web3 to artists and fans". Linkedin. 2022-05-10. Archived from the original on 2022-05-28. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- "Breaking: @HivemindCap and @Algorand today announced the acquisition of @Napster , to once again revolutionize the music industry by bringing blockchain and Web3 to artists and fans. Music industry veteran Emmy Lovell has been named interim CEO". Twitter. 2022-05-10. Archived from the original on 2022-05-10. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- Menn, Joseph (2003). "All the Rave: The Rise and Fall of Shawn Fanning's Napster". Crown Business. ISBN 0609610937.

- John Alderman (August 8, 2001). Sonic boom: Napster, MP3, and the new pioneers of music. Perseus Pub. ISBN 978-0-7382-0405-5. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- Napster wounds the giant : Music Archived 2009-06-01 at the Wayback Machine. The Rocky Mountain News (January 5, 2009). Retrieved on January 29, 2011.

- "Information Security News: Napster founder has cameo role in 'Italian Job'". seclists.org. Archived from the original on 2018-03-27. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- Kirkpatrick, David. With a Little Help From His Friends Archived 2015-01-21 at the Wayback Machine. Vanity Fair. October 2010.