Jorge Newbery

Jorge Alejandro Newbery Malagarie (27 May 1875 – 1 March 1914) was an Argentine aviator, civil servant, engineer and scientist.

Jorge Newbery | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 27 May 1875 |

| Died | 1 March 1914 (aged 38) Mendoza Province, Argentina |

| Occupation(s) | Aviator Engineer |

| Relatives | Eduardo Newbery |

Early and personal life

His father, Ralph Lamartine Newbery Purcell (born 1848) was a dentist who emigrated from Long Island, New York, and settled in Argentina after the American Civil War, in which he fought on the Union side of the Battle of Gettysburg and was recognized for his courage.[1][2]

Historical context

Newbery was in the public eye between the 1890s and the first fifteen years of the 20th century, a very important time for Argentina which was characterised by an enormous immigration of Europeans which multiplied the country's demographic importance by a factor of five. The population of Argentina, which represented 0.12% of the global population in 1869, would come to make up 0.57% of mankind in 1930. and the expansion of an economy of agricultural export which increased the GDP per capita from $334 in 1875 to $1,151 in 1913.[3]

The Newbery years were years of unshakeable faith in the possibilities of Argentina, when Rubén Darío wrote in his famous Canto a la Argentina y otros poemas: "Argentina, your day has come!"[4] These years saw the appearance of tango, Vaslav Nijinsky dancing in the Teatro Colón, the opening of the Buenos Aires Metro, the arrival of Guglielmo Marconi in Argentina in order to carry out the first radio-telephonic communication with Ireland and Canada.

Biography

Son of American-born dentist Ralph Newbery, Jorge was born 27 May 1875[5] in the family home on Florida Street, Buenos Aires. At the age of eight he visited the United States alone. Later, back in Argentina, he studied at Saint Andrew's Scots School, graduating from secondary school in 1890, and subsequently traveled to the United States to study engineering at Cornell University. In 1893 he continued his studies at the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia, where he was a student of Thomas Edison, and in 1895 earned a degree in electrical engineering.

On returning to his home country he began working as the head of the "Rio de la Plata Light and Traction Company". In 1897 he joined the Argentine Navy as electrical engineer during the border conflicts with Chile. He worked as a swimming teacher at the Naval School, and in 1899 he was sent to London to acquire electrical materials. His naval career lasted until 1900, when he was named Director General of Electrical, Mechanical and Lighting Installations of the Municipality of Buenos Aires City, a public role which he would hold until his death.

In 1904 he became Professor of Electrical Engineering at the National Industrial School (later the Otto Krause Technical School), which was founded and directed by the engineer Otto Krause in 1893. In the same year he travelled to the United States once more to attend the International Electricity Congress which took place in the city of Saint Louis, where he was vice president of the section on "Power and Light Transmission" and at which he presented an eighty-page work entitled "General considerations on the transfer of lighting services to municipal ownership", which would be included in the Annals of the Argentine Scientific Society.[6]

Aerostatics and balloons

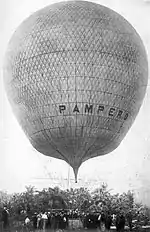

Jorge Newbery began wanting to rule the skies when he met the Brazilian aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont (1873–1932). On 25 December 1907, Jorge Newbery and Aarón Anchorena crossed the Río de la Plata in the balloon El Pampero before landing in Conchillas, Uruguay. Although there had been a few previous balloon flights in Argentina, the crossing of the Río de la Plata became a popular event. El Pampero set out from the Sociedad Sportiva Argentina, located in Palermo, on the same land where Campo Argentino de Polo is located nowadays.

A few days later, on 13 January 1908, the Aero Club Argentino was created, with Aarón Anchorena as president and Jorge Newbery as second vicepresident. The ACA was located on the Villa Los Ombúes estate of local business tycoon Ernesto Tornquist, in Barrancas de Belgrano, Buenos Aires (since torn down and now the location of the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany).[7] On 17 October his brother Eduardo (also an ACA member), together with Seargent Romero, went missing in El Pampero and their bodies were never found. These were the first two casualties in the history of flight in Argentina. Despite the tragedy and public opinion starting to consider balloon-flight to be excessively dangerous, Newbery prepared a new balloon, El Patriota, and revitalised aerostatics with the help of socialist representative Alfredo Palacios. One month after the death of his brother, on 24 November, Jorge married Sara Escalante.

On 9 April 1909, Newbery wrote the first newspaper article on aviation in Argentina. Entitled "Aeronáutica", the article was featured in the Buenos Aires El Nacional. By that time, Newbery was already a seasoned aerostat pilot, having flown these balloons four times over the Argentine landscape. He had not, however, been in or even seen a heavier-than-air craft before he wrote the article. While Newbery had promised both his mother and his wife that he would not attempt to fly again after his brother's aerial death, the article showed his family that he had broken that promise, resulting in his divorce from Escalante, with whom he had at least one child.

Newbery flew an aerostat round-trip for the first time on 24 January 1909, making his second round-trip flight on 2 April. On 27 April, just eighteen days after publication of the aforementioned article, he was elected president of the same Aero Club Argentino which he had previously served as second vice-president. Newbery accepted, with the hope of turning around the club's dire financial situation, and continued as president until his death in 1914.

He soon acquired another balloon, El Huracán, with which on 28 December 1909 he broke the South American record for duration and distance by travelling 550 km in 13 hours, linking Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil, and reaching fourth place worldwide in terms of flight time and sixth place in distance. This balloon gave its name to one of the most popular football clubs in Buenos Aires, the Club Atlético Huracán, founded on 1 November 1908 and nicknamed "globo" (balloon). On 5 November 1912 he broke the South American altitude record, reaching 5,100 m in the balloon Buenos Aires.

He took part in the Exposición Internacional del Centenario (1910) in Buenos Aires by making balloon ascents over the exhibition so that visitors could view the surrounding area of Palermo and the river.

Newbery made 40 balloon flights in three years. There were other Argentine aviators at this time, such as Eduardo Bradley, Lieutenant Angel María Zuloaga, Aníbal Brihuega and Pedro Zanni. Later, in memory of his brother, he had a 2,200 cubic meter balloon called Eduardo Newbery built, the largest that had ever been built in Argentina. In 1916, Bradley and Zuloaga crossed the Andes for the first time in this balloon.[8]

Aviation

In 1910, Newbery obtained his (provisional) pilot's licence, but continued to make balloon flights until 1912. As a direct result of Newbery and the Aero Club Argentino's offer to make their park freely available to the Ministry of War, on 10 August 1912 the President Roque Sáenz Peña created the Military Aviation School, the first Latin American air force. Jorge Newbery as a civilian, and Lieutenant Colonels Enrique Mosconi, later the director of YPF, and M. J. López were the first directors of the School, established in Palomar de Caseros.

The ACA organised a public collection with which the first aircraft were acquired. On 25 May 1913 they had their first parade: 4 monoplanes piloted by two civilians, Newbery and Macías, and two soldiers, Goubay and Agneta. A few months later the Army issued special insignia for the two military pilots. When choosing between monoplanes and biplanes, Newbery preferred the former.

On 24 November 1912, Newbery crossed the Río de la Plata in the monoplane "Centenario", a 50 HP Gnome powered Bleriot XI. He was the first to cross the river and return in the same day. Influenced by Newbery, the young Teodoro Fels, took an aeroplane from the Military Aviation School without permission and reached Montevideo, breaking the world record for flight over water. On his return, President Roque Sáenz Peña had him arrested and promoted to corporal for the feat.

On 10 February 1914, Newbery broke the world altitude record by 65 m, reaching 6,225 m in a Morane-Saulnier monoplane but the record was not ratified by the international commission because the previous record had not been exceeded by at least 150 m.[9]

Jorge Newbery arrived in Mendoza to attempt the first crossing of the Andes by aircraft. At the request of a woman who had seen him fly, he borrowed an aircraft from his friend Teodoro Fels, who warned him of a problem with the monoplane's wing. Jorge Newbery took off with Jiménez Lastra and did some aerobatics until 18:40, the monoplane fell violently. Jorge Newbery died in the Estancia "Los Tamarindos" in Mendoza (now Governor Francisco Gabrielli International Airport), on 1 March 1914, aged 38.[10][11]

The Aeroparque Jorge Newbery in Buenos Aires commemorates his pioneering work in the promotion of aviation in Argentina.[12] Villa Lugano in Buenos Aires claims the title of cradle of Argentine aviation, a claim also made by the district of El Palomar, seat of the First Aerial Brigade and previously the Military Aviation School. Newbery made his first flights in Villa Lugano, for which a monument was erected on the Avenida Teniente General Luis J. Dellepiane, close to Avenida Gral. Paz.

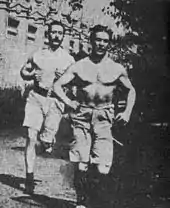

The sportsman

Newbery also excelled in boxing, swimming, motor racing, fencing and rowing, among other sports. In 1895 he took part in a historic fight to determine the superiority of boxing (defended by Newbery) or savate (defended by Carlos Delcasse), which established boxing as a popular sport in Argentina. He won important boxing titles in 1899, 1902 and 1903. On 8 July 1903 he decisively beat professional boxer Clark.

In October 1901 he won first prize for fencing with foils in the South American tournament organised by the Gymnastics and Fencing Club. In 1905 and 1906 he won the foil fencing contests organised by the Buenos Aires Jockey Club, where he also defeated the French swordfighting champion Berger.

On 16 March 1908, representing the Buenos Aires Rowing Club, he won the 1000 m race against the champion Müller brothers. In 1910 he joined the team which established the speed record for a boat with four long oars.

In 1902 he won the first prize in long-distance diving in the Luján river, covering 100 m. He was one of the personalities who most encouraged the practice of the sport in Argentina, although he is not well-remembered for this.[13]

In 1980 the Konex Foundation posthumously granted him the Konex Award for his supporting role in Argentine sporting history.

He also played football for National Foot–Ball Club, and in 1934 they changed their name to his.

The civil servant

Jorge Newbery was Director of the Lighting Service of the Municipality of Buenos Aires City until his death. As a civil servant, Newbery supported municipal control of lighting, contrary to the situation at the time in which the service was conceded to private companies.[14]

In 1903/1904 a great debate took place in Buenos Aires over the benefits of the public system versus the system of private concession. Newbery took an active role in the debate and wrote an extensive report entitled "General considerations on the transfer of lighting services to municipal ownership", which was published in the Annals of the Argentine Scientific Society, April–June 1904.

Among other arguments to support his position, Newbery wrote:

The necessity of such a defensive intervention is a direct consequence of the means by which capital is now used to maximise benefits, while these powerful groups have now found monopoly or union to be a safer or more productive basis for obtaining greater interest than previously offered by competition with each other.[15]

Newbery also dedicated himself to researching solutions for transportation and traffic in the city of Buenos Aires, suggesting in 1908 the elimination of trams and promoting new technologies of mass transport.[16]

The man of science

Newbery habitually wrote for the Annals of the Argentine Scientific Society. In 1906 he published a series of articles on the growing artificial graphite industry. In 1908 he published a study on the manufacture of "The electric incandescent light bulb called zirconium and other metallic filaments", based on his own laboratory tests, with the aims of implementing their use in Argentina.[17]

In 1910, in collaboration with the chemist Justino Thierry, he wrote a scientific-industrial book entitled "Petroleum" in which they argues for the necessity of keeping oil zones for the state.[16]

The popular figure

Newbery has been considered to be the first popular non-political Argentine idol.[18] Before his time, only political idols had existed. Crowds gathered to watch his aerial feats and the news media defined his as a "sportsman". In his promotion of sports, Jorge Newbery anticipated a still-embryonic lifestyle which focused on the development of the body and its potential, exercising self-control and training.

One characteristic of Newbery's personality was the absence of fear: he was known as "Mr Courage". Newbery's "feats" had enormous popular impact. For example, on breaking the South American record in the balloon "Huracán" in 1909, the Club Atlético Huracán asked Newbery if they could use the balloon's image as their club's emblem. In one paragraph of his response, the aviator said:

In response to your eloquent and courteous letter, in which you asked my agreement for your Club using the distinctive shape of the Huracán balloon, I give my complete agreement and hope that the "team" will wear it on their chests, which will give it the honour due to a sphere which in a single flight crossed three republics.[19]

The Club Atlético Huracán then adopted it as the symbol on their shirts, and after achieving two consecutive promotions (passing from the third division to the second, and thence to the first) the directorial commission sent Newbery a letter saying:

Huracán has done it. It played in three categories, just as your balloon crossed three republics, and thus we have fulfilled your wish.[19]

Jorge Newbery in popular culture

|

Corrientes y Esmeralda (excerpt) Amainaron guapos junto a tus ochavas

|

Jorge Newbery has been one of the most frequently mentioned people and one of the people to whom the most tangos have been dedicated. Among these must be mentioned the reference made by Celedonio Flores in the song Corrientes y Esmeralda, which mentions how "el cajetilla" (slang: a young, rich and refined man) hit the "guapos" (men fighting with knives) who "stopped" there at the beginning of the 20th century.

Other tangos dedicated to Newbery are "Jorge Newbery", by Aquiles Barbieri, "Prendete del Aeroplano", by José Escurra, "De Pura Cepa", by Roberto Firpo, "Newbery", by Luciano Ríos, "Un recuerdo a Newbery", by José Arturo Severino, "Tu Sueño", by Eduardo Arolas and "El Pampero", by Luis Sanmartino.[20]

A film was also made about his life: Más allá del sol (Beyond the sun, 1975), by Hugo Fregonese, with Germán Kraus in the leading role. The government of Buenos Aires annually awards the Jorge Newbery Prize to the most prominent sportspeople of the year.

The tragic death of Newbery helped to fix his position as an idol of Argentina, as later happened with Carlos Gardel. His funeral at Recoleta Cemetery was on a scale never seen before for a person unrelated to political activity. A mausoleum financed by public donations was built in 1937 at La Chacarita Cemetery.[21]

Airports

- The Aeroparque Jorge Newbery airport in Buenos Aires is named after him.

Schools

- School of technical aeronautics education number 8 "Jorge Newbery".

Football clubs

- Club Atlético Jorge Newbery[22] (Laprida, Buenos Aires, Argentina), founded 1 May 1917.

- Club Atlético Jorge Newbery (Aguilares, Tucumán Province, Argentina), founded 8 April 1917.

- Club Atlético Jorge Newbery (Venado Tuerto, Santa Fe Province, Argentina), founded 11 July 1917.

- Club Football Jorge Newbery (Junín, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina), founded 13 January 1913.

- Club Atlético Jorge Newbery (Rufino, Santa Fe, Argentina), founded 12 October 1917.

- Club Jorge Newbery Mutual Social y Deportiva, Ucacha, Córdoba Province, Argentina, founded 25 May 1910. https://web.archive.org/web/20090226194412/http://www.eam.iua.edu.ar/hist_newbery.asp

- Club Jorge Newbery de Versailles , Villa Real district, Buenos Aires City, Argentina founded 12 October 1942.

Streets

- Calle Jorge Newbery (Junín, Buenos Aires Province). The municipality renamed the street, previously named "Junín", on 12 March 1914, 11 days after Newbery's death.

- Calle Jorge Newbery (Venado Tuerto, Santa Fe Province). The Club Atlético Jorge Newbery is situated on this street.

- Calle Jorge Newbery (Viedma (Rio Negro)). This street is the main route of entry to this provincial capital.

- Calle Jorge Newbery (Rosario, Santa Fe). On this avenue is located the Rosario International Airport.

- Calle Jorge Newbery (Ucacha). This street is the main access to the premises of the Club Jorge Newbery, and was named on the club's centenary on 25 May 2010.

Train stations

- Jorge Newbery station (Hurlingham, Buenos Aires)

See also

- Aerostat

- History of aviation

- página de Wikipedia sobre Jorge Newbery (Español)

Notes

- "The Bradleys of Essex County Revisited" by Saul Montes-Bradley, 2004

- "Más liviano que el aire" by Nelson Montes-Bradley

- Cortés Conde, Roberto (1997). La economía argentina en el largo plazo (Siglos XIX y XX). Buenos Aires, Sudamericana y Universidad de San Andrés, pag. 29. ISBN 950-07-1231-8.

- Darío, Rubén. "Canto a la Argentina". Revista Versoados. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- "Día del Ingeniero Electricista".

- Larra, Raúl (1975). Jorge Newbery. Buenos Aires: Schapire, p. 29-41.

- "Castillo Villa Ombúes". Arcón de Buenos AIres. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- Larra, p. 55-93

- Larra, 172–175

- "redargentina.com". redargentina.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015.

- Los Andes. "Verdades del último vuelo de Newbery". Los Andes. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- Larra, p. 139-159

- Larra, p. 43-55

- Corbière, Emilio J. "Perfiles: Jorge Newbery". Club del Progreso. Archived from the original on 10 December 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- Larra, 115

- Larra, p. 109-139

- Houssay, Bernardo. "El ingeniero Jorge Newbery". Club del Progreso. Archived from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- Larra, p. 93

- Locos por el Globo. "Historia de Huracán". Club Atlético Huracán, Locos por el Globo. Archived from the original on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- Bruno Cespi. "Tango and daily events, Todotango.com". Todo Tango. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Lazzari, Eduardo (28 November 2018). "Jorge Alejandro Newbery pionero de la aeronavegación argentina (2ª parte)". www.nuevospapeles.com/. Nuevos Papeles. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- http://newberylaprida.blogspot.com.

Bibliography

- Larra, Raúl (1975). Jorge Newbery. Buenos Aires: Schapire.

- Historia del Club Huracán, Amigos de Huracán, archived from the original on 9 March 2007

External links

- Escuela de Aviación Militar: Homenaje a Jorge Newbery at the Wayback Machine (archived 26 February 2009) (in Spanish)

- Perfiles: Jorge Newbery, by Emilio Corbiere at the Wayback Machine (archived 10 December 2011) (in Spanish)

- Jorge Newbery in tango lyrics at the Wayback Machine (archived 29 March 2014) (in Spanish)

- Argentine newsreel with images of Jorge Newbery (video) (in Spanish)

- El Ingeniero Jorge Newbery at the Wayback Machine (archived 4 July 2010) (in Spanish)

- Jorge Newbery at the Wayback Machine (archived 29 March 2015) (in Spanish)

- Jorge Newbery, Promotor de la ciencia y la cultura at the Wayback Machine (archived 8 August 2007) (in Spanish)

- Jorge Newbery (Portal educativo Universidad de Mendoza) at the Wayback Machine (archived 10 July 2010) (in Spanish)

- Jorge Newbery, "el dueño del cielo" at the Wayback Machine (archived 15 December 2007) (in Spanish)

- Verdades del último vuelo de Newbery at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 September 2007) (in Spanish)

- Some information on Newbery's life Archived 23 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)