José Ángel Zubiaur Alegre

José Ángel Zubiaur Alegre (1918–2012) was a Spanish right-wing politician. Throughout most of his life he remained active as a Carlist militant and held some positions in the regional Navarrese party executive. In the 1970s he left the movement and contributed to birth of a Navarrista party, Unión del Pueblo Navarro. His career climaxed during the Cortes term in 1967–1971, when he strove to liberalize the regime and gained nationwide recognition. In 1948–1951 and 1983–1987 he served also in the regional Navarrese self-government.

José Ángel Zubiaur Alegre | |

|---|---|

| Born | José Ángel Zubiaur Alegre 1918 Bilbao, Spain |

| Died | 2012 Pamplona, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | lawyer |

| Known for | politician |

| Political party | Carlism, UPN |

Family and youth

The Basque Zubiaur family has been traditionally related to sea fare; its members appear in medieval records of the Biscay Consulate of the Sea and already in the mid-16th century Zubiaur was considered a very distinguished name.[1] Some of the family members grew to well known Spanish naval commanders[2] and in the early modern era the Zubiaurs were among 10 families most represented in the Bilbao town hall;[3] some held also official positions in the Señorío de Vizcaya.[4] The family got very branched;[5] in the early 19th century one arm emerged within ranks of the Basque petty bourgeoisie. Its descendant was José Ángel's grandfather, Vicente Zubiaur Unzaga, married in Bilbao to María Salazar Gochi. The couple had 7 children;[6] the second oldest one and the oldest son was José Ángel's father, Juan José Zubiaur Salazar (1888–1943).[7] He went on with trading business and set up companies on his own; one specialized in sales and maintenance of various tools, accessories and machinery,[8] another was dealing in import and repair of English automobiles.[9] In 1920–1922 he served as member of the Bilbao ayuntamiento.[10]

In 1890 Zubiaur Salazar married Teresa Alegre Navascués (1893–1975);[11] little is known about her family except that she originated from a Navarrese town of San Martín de Unx.[12] The couple settled in the very centre of Bilbao;[13] they had only one child. At unspecified time, though probably in the late 1920s, Zubiaur Salazar was interned in the psychiatric hospital in Bermeo; in 1926 his wife and son left Bilbao for San Martin de Unx,[14] where Jose Ángel passed most of his childhood;[15] though a Vizcaino by birth, he developed a strong Navarrese identity. In the late 1920s he entered a Marist school in Pamplona,[16] where he obtained bachillerato during the Republic era.[17] In 1934 Zubiaur enrolled at philosophy and letters at the University of Zaragoza. Outbreak of the Civil War interrupted his academic career; he resumed law studies after the war in Madrid and graduated in philosophy and letters and in law.[18]

In 1947 Zubiaur married María Josefa Carreño Cima (1918–2015).[19] The couple settled in Pamplona[20] though they used to spend much time in Leitza;[21] they had 7 children, the first one born in 1948. Their marriage endured 65 years; when passing away, Zubiaur had 23 grandchildren.[22] Two of Zubiaur's sons became public figures. The oldest one, José Ángel Zubiaur Carreño, held high administrative and economic offices in the Navarrese self-government and represented Navarre in various central EU bodies;[23] a longtime UPN politician, he left the party in 2013[24] and assumed more right-wing positions.[25] Francisco Javier Zubiaur Carreño held high jobs related to Navarrese culture and is professor in history of art, author of books related to painting, film and museology;[26] politically he tends to a more progressist stand.[27] Among other notable relatives,[28] Zubiaur's paternal uncle Román Zubiaur Salazar was a fairly popular comic actor, in the early 1920s known as a Basque stage character "Martinchú Perugorría".[29]

Republic and Civil War

_-_Fondo_Mar%C3%ADn-Kutxa_Fototeka.jpg.webp)

Zubiaur was born to a Carlist family;[30] his father knew personally the claimant Don Jaime and in the early 1910s he was involved in the Miguelist plot in Portugal.[31] José Ángel adopted the Carlist outlook as a natural way of life,[32] especially that also San Martín de Unx was part of the Carlist Navarrese heartland.[33] Already during his early schooling years the boy he was active in Juventudes Jaimistas, a Carlist youth organization;[34] during the Republican period he grew to executive positions within the organization, though information available is confusing.[35] Later Zubiaur admitted having taking part in Traditionalist Pamplonese feasts, though he remained silent on any organizational commitments of the early 1930s.[36] Following the coup of July 1936 he volunteered to the Carlist militia, the requeté,[37] and spent almost 3 years on the front;[38] he served mostly in one of field companies of Radio Requeté,[39] first in Tercio de Navarra and then in Tercio de Lácar.[40] He survived the Biscay, Santander and Asturias campaigns unharmed, until during the Battle of Teruél he suffered frostbites and had to be treated in the Pamplona hospital[41] He finished the wartime career as a sergeant.[42]

According to some sources already in early 1937 Zubiaur was engaged in Carlist propaganda activities in the Navarrese rearguard.[43] He apparently complied with the Unification Decree and was incorporated into the new Francoist state party, Falange Española Tradicionalista. In late 1938 he was nominated the provincial Navarrese head of the FET propaganda section[44] and at this role he remained active at least until 1939. Some historians consider him a representative of "carlismo colaboracionista",[45] According to some sources he entered Junta Consultiva Nacional of SEU, the new academic organisation set up by the regime.[46]

Though the member of FET, Zubiaur kept considering Manuel Fal Conde his political leader[47] and protested against the exaltation of Falangism at the expense of Traditionalism.[48] He also took advantage of his position in the emerging Francoist structures to cultivate and promote the Carlist outlook. He presided over local feasts to honor the Traditionalist fallen,[49] called for the Carlist kings to be buried at Escorial[50] and at the Navarrese border officially welcomed remnants of general Sanjurjo, to be laid to grave during a solemn funeral ceremony in Pamplona.[51] His most lasting initiative, however, was setting up Hermandad de Caballeros Voluntarios de la Cruz, a hardly veiled Carlist ex-combatant organisation; it was intended as counter-proposal to the official Delegación Nacional de Excombatientes and was to group former requetés only.[52] In 1939 Hermandad helped to launch two periodical Navarrese feasts, formatted as homages to the Traditionalist fallen and demonstrations of Traditionalist principles: a female pilgrimage to the top of Montejurra[53] and a male pilgrimage to the castle of Javier.[54] Supposed to embody "the spirit of July 18",[55] according to later accounts they were intended as dissident manifestations of genuine patriotism, opposed to Francoist distortion of "espíritu de la Cruzada".[56]

Early Francoism

There is little information on Zubiaur's activity in the early 1940s. It seems that he left the FET propaganda structures; it is not clear whether he spent the years completing his university education in Madrid or remained in Navarre.[57] According to imprecise and enigmatic accounts he was active in the Carlist academic organisation AET,[58] re-organized Juventud Carlista in Pamplona[59] or worked to re-build the entire Carlist Navarrese structures.[60] According to his own later accounts Zubiaur remained loyal to the Carlist regent Don Javier[61] and indeed in 1946 he was recorded as touring rural Navarre, busy reviving the semi-clandestine Javierista organisation.[62] Prior to first local elections staged in the Francoist Spain Zubiaur engaged in the open Carlist propaganda campaign and was soon appointed as a candidate to the Pamplona city council himself. As a semi-official Carlist contender he stood in a pool named Tercio Familiar and was elected in 1948.[63] As Carlist contingent in the ayuntamiento gained strength, the council delegated him to Diputación Foral, a 7-member Navarrese self-government.[64]

Politically Zubiaur's term as city counselor and provincial deputy is marked mostly by confrontation between the Falangist civil governor, Luis Valero Bermejo, and the Traditionalist municipal and provincial delegates.[65] Some sources note him and Jesús Larrainzar as key opponents of FET in both bodies,[66] others do not mention his name when reconstructing the Carlist-Falangist struggle for power.[67] At Diputación Zubiaur was responsible for culture and education; he took advantage of his position to promote Traditionalism and worked to turn Institución Príncipe de Viana, a provincial cultural and educational centre, into a Carlist outpost.[68] He was also responsible for classes of Basque, sponsored by Diputación[69] and launched despite obstruction mounted by Valero;[70] the courses went on until 1970. Zubiaur's term in the city council expired in 1951; according to some sources he tried to renew the ticket, but failed.[71] However, fellow Carlists in local structures ensured that in 1952 he was appointed Subdirector de Hacienda de Navarra, deputy head of the self-governmental economic department; at later date he would grow to director of the unit.[72]

In the early 1950s Zubiaur counted among the most anti-regime Navarrese Carlists;[73] some name him "leader of anti-Francoist sector".[74] He was noted delivering intransigent harangues at Montejurra rallies[75] and in 1954 was engaged in launch of a clandestine party bulletin, El Fuerista;[76] according to some authors he was its "redactor principal".[77] The initiative did not go unnoticed by the authorities;[78] despite his professional standing as a lawyer[79] the same year he was repeatedly briefly detained by the security.[80] He emerged as one of key provincial party activists, already in touch with the regent;[81] given the local executive was in hands of older politicians, some proposed that he forms part of Secretariado, a 4-member auxiliary body which would lead buildup of the party structures.[82] In 1956 he was first noted as taking part in Madrid sittings of Consejo Nacional, the nationwide executive of the Carlist organization Comunión Tradicionalista, and came to know his king personally.[83]

Mid-Francoism

In the mid-1950s the intransigent Carlist policy gave way to a conciliatory course, engineered by the new political leader José María Valiente. Zubiaur was initially counted among the "guipuzcoanos",[84] a hardline faction opposing the new strategy. In 1956 he took part in works of Junta de las Regiones, a somewhat rebellious body contesting the collaborationist policy. Some scholars consider him the leader of the group[85] who challenged Valiente over his firm grip on leadership, denounced as centralizing and anti-fuerista style.[86] When the aging Navarrese jefé Joaquín Baleztena was about to resign, in 1957 the hardliners mounted a scheme to get him replaced by Zubiaur,[87] yet the job eventually went to Valiente's man of confidence, Francisco Javier Astraín. Zubiaur welcomed arrival of prince Carlos Hugo on the Spanish political scene.[88] In 1958 he called to join ranks behind Don Javier and the Borbón-Parmas against any temptations of reconciliation with the Juanistas;[89] speaking at Montejurra in 1959 he demanded unreserved support for Carlos Hugo.[90] In the early 1960s Zubiaur was one of the best recognized Navarrese Carlists;[91] at increasingly massive Montejurra rallies he was the second most frequent speaker after Valiente[92] and in absence of the prince used to read manifestos on his behalf,[93] occasionally delivering addresses also beyond Navarre.[94]

When faced with growing conflict between the Traditionalists and the Hugocarlistas he sided with the latter. Impressed by dynamics of the young prince and his sisters, he believed that they were "renewing the pact" between the Carlist people and the Carlist royal family.[95] He did not join skeptics who started to leave the Comunión, kept bombarding Valiente with letters urging re-organisation of the party,[96] published articles demanding total loyalty to the Borbón-Parmas,[97] welcomed the new model of Catholicism forged at Vaticanum II,[98] supported the new policy of consulting the Carlist rank-and-file about the party course[99] and saturated his own public addresses with new phraseology focused on "liberties" and "human personality".[100]

In 1961 Zubiaur was considered a candidate for a new, vasco-navarrese Carlist junta;[101] in 1964 he was confirmed as secretary to the Navarrese executive, still headed by Astraín.[102] Eventually, when Astraín resigned in 1966 he was replaced with a 5-member committee, headed by Zubiaur;[103] the latter was to rebuild the regional organisation that he had been criticizing for years as ineffective.[104] He fully endorsed changes in the Comunión introduced in 1966 as doing away with centralized structure and infusing the fuerista spirit into the organization; in fact, they were intended to fragment power and facilitate Hugocarlista takeover of the party.[105] However, the prince and his entourage did not trust Zubiaur; though they thought him "more modern" than Valiente and the likes,[106] in the mid-1960s they still considered it necessary to manipulate written versions of his public addresses to make them appear more progressive.[107] Zubiaur was not appointed to the new nationwide bodies like a 36-member Consejo Asesor, set up in 1966.[108]

Late Francoism

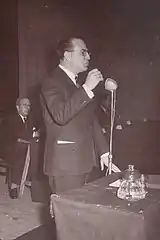

In 1967 the Francoist legislation introduced partial and semi-free elections to the Cortes; less than 20% of all deputies, a so-called tercio familiar, were to be chosen by direct vote of heads of families and married women. In Navarre Zubiaur[109] and Auxilio Goñi stood as unofficial Carlist candidates[110] and decisively defeated contenders supported by the administration;[111] they have eventually formed a 4-member informal Traditionalist minority in the chamber.[112] The following 4 years turned to be the period of their hectic parliamentarian activity; it was aimed at dismantling at least some dictatorial features of the regime, opposing new syndicalist designs and promoting more democratic legislation. The initiatives gained attention of nationwide media and were extensively reported in the press, posing more problems for the regime than it might have initially appeared.

Zaubiaur's bid for entry into Comisión Permanente of the diet failed,[113] but he and other Carlist deputies[114] immediately launched public campaign to change the role of the Cortes from "producción de leyes" – i.e. rubber-stamping drafts prepared by administration – into a platform of "effective dialogue" between the people and the government.[115] He then proceeded to suggest a number of changes in internal Cortes rules,[116] almost openly denounced current representation scheme as fictitious, condemned excessive centralism[117] and demanded more weight for tercio familiar.[118] Unable to get adequate hearing,[119] Zubiaur and a handful of other MPs started to stage rump sessions in various locations,[120] the practice which became known as "Cortes transhumantes".[121] It caused great irritation of the administration and was eventually prohibited by minister of interior in 1968,[122] though Zubiaur tried to revive the sessions as late as in 1970.[123]

In 1968 Zubiaur and few other deputies campaigned against the draft law on state secrets;[124] outvoted, they opposed the launch of constitutional process for Equatorial Guinea claiming that access to information related was severely restricted.[125] The same year the Carlists demanded re-introduction of separate provincial establishments for Gipuzkoa and Biscay, scrapped in 1937; isolated, during the vote they left the chamber in protest.[126] In 1969 Zubiaur a number of times protested against expulsion of prince Carlos Hugo from Spain[127] and afterwards in presence of Franco cast his vote against designation of prince Juan Carlos as the future king of Spain;[128] the same year he opposed the new "gobierno monocolor".[129] In 1970 he tried to relax the draft of education law[130] to ensure "pluralismo y subsidiaredad"[131] and mounted opposition against the proposed Ley Sindical.[132] In a public debate which took months[133] he stood in defense of syndicalist "pluralismo asociativo a ultranza".[134] Perfectly aware of his minoritarian position Zubiaur – dubbed "el viejo zorro carlista"[135] – approached the legislative exercise as means of stirring public opposition and using the rules of the regime to dismantle it from within.[136] In 1970 and 1971 he mounted another fierce campaign against the draft Ley de Orden Público[137] and in favor of new electoral legislation.[138] When his Cortes term expired in 1971 Zubiaur was recognized far beyond Navarre and far beyond the Carlist realm.

Breakup

In the late 1960s Zubiaur seemed fully aligned with the Hugocarlistas.[139] He got appointed to a 4-member Consejo Real,[140] was hailed by Hugocarlista press as embodiment of a "spirit of dialogue",[141] toured Carlist princes across Spain,[142] remained in the Navarrese party executive[143] and saw off expulsed Don Javier to the French border.[144] His 1969 address at Montejurra was particularly belligerent; it was branded subversive by the security[145] and earned him a massive, 50,000 ptas fine.[146] In 1970 he was among the party heavyweights invited to Lignières, where Carlos Hugo presented his newly born son.[147] The same year Zubiaur was appointed to Gabinete Ideológico, a body set up to preside over modernization of Carlism, and joined its foral commission;[148] moreover, he suggested that Pedro José Zabala, the party champion of progressism, gets appointed as head of the Gabinete.[149] He opposed the Traditionalist re-claim of El Pensamiento Navarro.[150] At the time when Hugocarlistas were increasingly embracing socialist rhetoric, in 1971 Zubiaur tried to mediate during strike at the Pamplona Eaton Ibérica plant and accepted by the workers, was rejected by the management.[151] As member of Carlist Junta de Gobierno he co-signed a lengthy manifiesto which demanded political liberties and vaguely pointed to "Federación de las Repúblicas Sociales".[152] Some scholars claim that Zubiaur significantly contributed to modernization of Carlism.[153]

Nothing is known about Zubiaur's unease about increasingly left-wing stand of Carlos Hugo,[154] though the prince did not trust him and some Hugocarlista ideologues tried to instruct Zubiaur on principles of the new Carlism.[155] In course of the 1971 electoral campaign to the Cortes he and Goñi seemed obvious party candidates, yet at one point the Borbón-Parmas asked them to sign an undated resignation letter, to be filed in the Cortes in case they lose trust of the claimant.[156] Enraged and humiliated both Goñi and Zubiaur refused, though they agreed to endorse their replacements.[157] This did not amount to total breakup; in 1972 Zubiaur defended in court the Hugocarlista youth from the terrorist GAC organisation, charged with attempt to sabotage Franco's radio address.[158] However, he did not take part in massive rallies staged in Southern France as "congresses of Carlist people", which led to transformation of Comunión Tradicionalista into Partido Carlista. In 1973 he openly complained about totalitarian schemes ruling within the new party.[159] In 1974 together with some other ex-MPs he was already working to set up a quasi-party as permitted by new Francoist legislation on political associations; it was rumored to be flavored with Carlism and regionalism.[160]

In early 1975 the senile Don Javier abdicated in favor of Don Carlos Hugo; this prompted many Traditionalists to challenge the latter with an ultimative letter, demanding confirmation of orthodox Carlist principles. Zubiaur is not listed among the signatories; however, as they had received no reply, he co-signed a second letter. Pointing to the so-called "double legitimacy theory" the document denied Don Carlos Hugo any Carlist credentials and marked Zubiaur's ultimate political breakup with the Borbón-Parmas.[161]

Transición

Zubiaur did not join efforts of Traditionalists like Zamanillo or Valiente, who tried to set up a Carlist political association.[162] Following the death of Franco he contributed to the series of lectures named "conferencias de Larraona" which in turn gave birth to Frente Navarro Independiente.[163] The party comprised various heterogeneous groupings including the local socialists; Zubiaur and the Carlists he tried to place in the organisation[164] formed its right wing.[165] FNI formally emerged in 1977.[166] He was initially considered a candidate for the Cortes campaign but resigned over internal differences and soon left FNI altogether.[167] He toured the country evaluating opportunities to build a new formation and later described himself as "a widower of Carlism, who tries to find a mother for his children".[168]

The new constitution opened path for incorporation of Navarre into a future autonomous Basque region. Zubiaur suggested to PNV leaders that Navarre is united with Vascongadas in one autonomous unit[169] given ikurriña is not adopted as its standard and "Euskadi" is not adopted as its name.[170] Once the proposal was rejected he felt compelled to defend regional identity against the Basque designs,[171] the task he was well positioned to undertake as recognized expert on Navarrese foral regulations,[172] author of numerous booklets,[173] more systematic works[174] and since 1977 as member of Consejo de Estudios de Derecho Navarro.[175] In 1979 together with other centre-right politicians[176] Zubiaur set up Unión del Pueblo Navarro, a party focused on protection of Navarrese self against the Basque nationalism and on loyalty to Christian values against the secularization tide. He entered the 8-member Comité Ejecutivo of UPN[177] and turned to be one of its most active militants. He was touring Navarrese towns and villages during the electoral campaign,[178] though his own bid for Senate failed.[179] Zubiaur was also among key men forging the electoral strategy, which included rejection of alliances with other parties; with some 15% of votes[180] UPN emerged as the third political force in Navarre.

In the early 1980s UPN overtook UCD and with some 25% of votes cast in Navarre it was second only to PSOE. At that time Zubiaur, whose term in the party executive expired in 1981,[181] was engaged mostly in debate on reform of formal regulations[182] and remained among the key party pundits,[183] actively speaking in public e.g. when denouncing the ETA campaign of violence.[184] In 1983 he was elected to the Navarrese parliament[185] and soon he became the protagonist of a legal debate which because of its potentially grave constitutional impact kept occupying the Spanish media for months. He was 4 times rejected by PSOE deputies as candidate for premiership of the Navarrese self-government, yet the socialists were unable to field their own competitor.[186] As a way out of the deadlock the parliament president submitted Zubiaur's candidature for approval to Madrid anyway.[187] The government directed the case to the Constitutional Tribunal,[188] which in 1984 declared Zubiaur's appointment invalid[189] and opened path for election of a socialist counter-candidate, Gabriel Urralburu.[190]

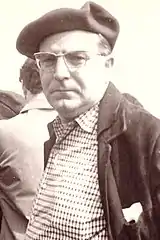

Last years

From 1983 till 1987[191] Zubiaur served as the UPN deputy in the Navarrese parliament, active in Comision de Regimen Foral, Comisión de Educación y Cultura, Comisión de Industria, Comercio y Turismo and Comisión de Control Parliamentario de Ente Publico Radio Television Navarra.[192] During his terms he kept standing for centre-right Navarrismo, still fiercely pitted against the Basque nationalism. One of his most lasting initiatives is foundation of Universidad Pública de Navarra,[193] which as member of the Education Committee he promoted and formatted as a publicly funded school.[194] He was also active in a number of regional bodies, e.g. serving as president of Junta Superior de Educación, and in commercial companies controlled by the self-government, e.g. as member of consejo de administración of Caja de Ahorros de Navarra.[195]

In the late 1980s Zubiaur turned 70 and was already a political retiree. However, occasionally he was rumored to be appointed as a Navarrese deputy to the Senate,[196] especially that in the late 1980s UPN overtook PSOE and became the first political power in Navarre. His position within the party was this of a prestigious patriarch, though at times he got involved in an increasingly visible confrontation between the intransigent Jesús Aizpún Tuero and the more conciliatory Juan Cruz Alli Aranguren;[197] Zubiaur supported the latter and he was counted among members of "plataforma renovadora".[198] Prior to the anticipated deadlock at the IV UPN Congress of 1993 he unexpectedly declared himself ready to run for the party leadership, greeted by the press as "histórico Zubiaur";[199] he ran indeed, but his 339 votes gained proved no match for 1,444 votes of Aizpún and he did not even make it to the party Comité Ejecutivo.[200]

Since the mid-1990s Zubiaur withdrew from politics, though not entirely from public life; profoundly religious, he remained active in various Catholic organizations like Hermandad de la Pasión[201] and voiced out in favor of Christian values and Christian family;[202] he also kept working on his memoirs.[203] He retained Traditionalist outlook and sentiment for Carlism, presented as a romantic, gallant and idealistic commitment from the past; however, in 2001 he considered the movement already dead. All he could have wished for was that Carlism be "at least remembered",[204] the stance by some described as "extreme pessimism".[205] According to few accounts he remained "integrista irreconcilable" who neared the Carlist branch led by Don Sixto,[206] yet in 2010, when in wheelchair assisting in opening of Museum of Carlism in Estella, he seemed on amicable terms with Don Carlos Hugo and his son Don Carlos Javier, whom he had greeted as a newborn baby 40 years earlier in Lignières.[207] In his last interview, given some 13 months before death, he appeared a serene and cheerful man.[208]

Notes

- Manuel Gracia Rivas, En el IV Centenario del fallecimiento de Pedro de Zubiaur, un marino vasco del siglo XVI, [in:] Itsas Memoria. Revista de Estudios Marítimos del País Vasco 5 (2006), p. 158

- the best known of them was Pedro de Zubiaur, famous for his numerous victories over the English navy in the late 16th century. For details, see Francisco Javier Zubiaur Carreño, Pedro de Zubiaur. Intrépido marino, militar, corsario y espía, [in:] ZubiaurCarreno service, October 2019, available here

- Mikel Zabala Montoya, El grupo dominante de Bilbao entre los siglos XVI y XVII: bases de poder y estrategias de reproducción a la luz del capitulado de concordia, [in:] Brocar. Cuadernos de Investigacion Historica 26 (2002), p. 56

- Imanol Merino Malillos, "Verdadero descendiente de mis antiguos señores". El Señorío de Vizcaya y los miembros de la familia Haro en el siglo XVII, [in:] Studia historica. Historia moderna 38/1 (2016), p. 265

- one of its arms settled in Alava. The great-grandfather of José Angel Zubiaur Alegre, Pedro Zubiaur Galíndez (1825–1890), was a native of Llodio, see the Pedro Zubiaur Galíndez entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- see Zubiaur Salazar entries at Consulta de Registros Sacramentales (1501–1900), [in:] Archivo Histórico Eclesiástico de Bizkaia service, available here

- Juan José Zubiaur Salazar entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- Arce y Compañia was formed jointly with Martín Millán de Arce Fernández and Luis Vilasau Torra. Its business was purchase, sale, construction and installation of machinery, tools and accessories, with the capital of 100,000 ptas, La Actualidad Financiera 28.03.17, available here

- Ducros and Zubiaur was set up jointly with Jesus Ducros; its business was construction and repair of all kinds of luxury carriages and car bodies, national and foreign commissions and representation; its capital was 25,000 ptas, compare La Accion 28.07.18, available here

- Joseba Agirreazkuenaga, Gizarte arazoak eta politikagintza Bilbon 1917–1922. Coyuntura social y política, [in:] Bidebarrieta. Anuario de humanidades y ciencias sociales de Bilbao (2000), p. 198

- she spent her senile years with her only child in Pamplona, José-Ángel Zubiaur Carreño, "El Fuerista. Órgano antiborreguil" (3), [in:] Cabos sueltos y retales de la Historia reciente blog 31.03.17, available here

- she was daughter to Nicanor Alegre Lopez and Eduvigis Navascues Janices, see Agustin Alegre Navascues entry, [in:] Geneaordonez service, available here

- the family house was located in the Santos Juanos parish, Roman Zubiaur entry, [in:] Bizkaitar entzutetsuen galeria, available here Archived 2018-08-22 at the Wayback Machine; Jose Angel was baptized in the church of San Vicente de Paúl in Bilbao

- until 1922 Zubiaur Salazar was recorded as serving in the Bilbao town hall

- Jose Angel first went to school in Colegio de las Madres Carmelitas (Vedrunas) in Bilbao, but has completed education in San Martín de Unx

- since then his relationship with San Martín de Unx was intermittent; he used to spend some holidays there

- José Angel Zubiaur Alegre, Epilogo, [in:] Eusebio Ferrer Hortet, Maria Teresa Puga Garcia, Los reyes que nunca reinaron, Barcelona 2015, ISBN 9788489644601, page unavailable, see here

- Don Jose Angel Zubiaur Alegre: un político Carlista, [in:] Navarra Confidencial 25.03.12, available here

- María Josefa Carreño Cima entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here. She originated from Asturias and in the mid-1940s lived in Madrid, yet the couple met in 1943 in Pamplona during a religious feast of Los Luises, Letizia Correa Ruiz, "El secreto es quererse y nada más", [in:] Nuestro Tiempo 666 (2011), available here

- their first child was born in Pamplona, see José Ángel Zubiaur Carreño. Director General de Asuntos Europeos y Planificación CV, available here

- Zubiaur's in-laws lived in Leitza

- Correa Ruiz 2011, ABC 01.04.16, available here

- José Ángel Zubiaur Carreño. Director General de Asuntos Europeos y Planificación CV, available here

- José-Angel Zubiaur Carreño abandona UPN, [in:] Navarra confidencial 19.06.13, available here

- see e.g. Manifiesto por la historia y la libertad document that protested the Ley de Memoria Histórica praxis, available here; see also his blog Cabos sueltos y retales de la Historia reciente, available here

- Francisco Javier Zubiaur Carreño, Currículum, [in:] Zubiaurcarreno service, available here

- e.g. he supported the idea of turning what used to be the Pamplona Mausoleo a Los Caidos into a museum, Pilar Fernandez Larrea, La memoria histórica no es solo la reciente, también la de siglos pasados, [in:] Diario de Navarra 08.04.17, available here

- Zubiaur's brother-in-law, Francisco Javier Carreño Cima, gained some recognition in tourist business and education, see Fallece Fco Javier Carreño Cima, [in:] Centro Español de Nuevas Profesiones service 13.08.18, available here Archived 2018-08-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Roman Zubiaur Salazar was initially the author of costumbrista dramas, played mostly at popular Carlist feasts. However, he gained more popularity in the 1920s as an actor, playing Basque characters in Bilbao and in Madrid; he was the key protagonist in one of the first movies featuring Basque language, Martinchu Perugorría en Día de Romería (1925), Roman Zubiaur entry, [in:] Bizkaitar entzutetsuen galeria, available here Archived 2018-08-22 at the Wayback Machine, Eduardo Vasco San Miguel, Para una historia de la voz escénica en España [PhD thesis Complutense], Madrid 2017, p. 54

- In memoriam José Ángel Zubiaur Alegre, [in:] Comunión Tradicionalista service 27.03.12, available here Archived 2018-08-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Ferrer Hortet, Puga Garcia 2015

- Ferrer Hortet, Puga Garcia 2015

- San Martin de Unx was home to a Carlist general José Lerga, compare José Mari Esparza Zabalegui, Jose Mari Esparza, Abajo las quintas!: la oposición histórica de Navarra al ejército español, Tafalla 1994, ISBN 9788481369199, p. 272; Joaquín Muruzabal, considered the first requeté fallen in the Civil War, originated from San Martin; for the role of Carlism in the town in the 1970s compare also Personajes e historias de San Martin de Unx, [in:] sanmartinunx blog service, available here

- In memoriam José Ángel Zubiaur Alegre, [in:] Comunión Tradicionalista service 27.03.12, available here Archived 2018-08-22 at the Wayback Machine

- in some sources Zubiaur is referred to as "president of the jaimista youth", compare Daniel Jesús García Riol, La resistencia tradicionalista a la renovación ideológica del carlismo (1965–1973) [PhD thesis UNED], Madrid 2015, p. 231; "Jaimistas" was the term used widely until 1931, when Zubiaur was 13 years old

- Ferrer Hortet, Puga Garcia 2015

- García Riol 2015, p. 231

- Zubiaur once confessed that during the Civil War he had spent 3 years "sleeping on the ground and eating sardines ", Correa Ruiz 2011

- García Riol 2015, p. 231; see also José Javier Nagorne Yárnoz, Recuerdos, [in:] Fundación Ignacio Larramendi service, available here

- García Riol 2015, p. 231

- Don Jose Angel Zubiaur Alegre: un político Carlista, [in:] Navarra Confidencial 25.03.2012, available here

- García Riol 2015, p. 231

- Pensamiento Alaves 22.01.37, available here

- García Riol 2015, p. 231. For a sample of his endeavors as a Falangist propaganda jefe see e.g. a circular issued prior to a homage feast for José Antonio Primo de Rivera, José Andrés Gallego, Antón M. Pazos (eds.), Archivo Gomá: documentos de la Guerra Civil, vol. 12, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788400088002, pp. 293-294

- Zira Box Varela, La fundación de un régimen: la construcción simbólica del franquismo, Madrid 2008, ISBN 9788469209981, p. 153

- Imperio 04.11.39, available here

- Manuel Martorell Peréz, Navarra 1937–1939: el fiasco de la Unificación, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 69 (2008) p. 447

- in early 1939 Zubiaur protested to Minister of Interior over a propaganda film España heroica by Joaquín Reig Gozalbes; it presented the Northern campaign as almost exclusively the Falangist effort. Zubiaur dubbed some parts of the film as tendentious, to claim later that “hiriendo el espíritu imparcial del público navarro … Legítimo es el hacer resaltar la labor de Falange, pero ¿hay derecho a silenciar la otra, la Tradicionalista? Es más, ¿conviene hacerlo?”. He went on to say that Spain "no tolera que se falsifique la historia y a la que no se puede humillar, ni aún siquiera de buena fe, en sus afectos”. He alluded to unrest that had taken place during the screening in Pamplona and suggest the film is no longer screened "si se había de evitar un día de luto en Pamplona”, Rosa Álvarez Berciano, Ramón Sala Noguer, El cine en la Zona Nacional 1936-1939, Bilbao 2000, ISBN 8427123019, pp. 142-143, 240; Emeterio Díez Puertas, El montaje del franquismo. La política cinematográfica de las fuerzas sublevadas, Barcelona 2002, ISBN 8475844820, pp. 270-271; Alberto Cañada Zarranz, El cine en Pamplona durante la II República y la Guerra Civil (1931-1939), Pamplona 2005, ISBN 8423528073, p. 175

- Box Varela 2008, p. 153

- Pensamiento Alaves 04.04.39, available here

- ABC 18.10.39, available here

- Hermandad was conceived as counter-organization to Delegación Nacional de Excombatientes; it was supposed to be a strictly ex-requeté organisation. Its Consejo Supremo comprised José Ángel Zubiaur Alegre (as caballero subprior), Cesáreo Sanz Orrio, Félix Abárzuza Murillo, Jaime del Burgo Torres and Ignacio Baleztena, Fernando Mikelarena, Víctor Moreno, José Ramón Urtasun, Clemente Bernad, Txema Aranaz y Pablo Ibáñez Del Ateneo Basilio Lacort, Javierada y derecha navarra, [in:] Noticias de Navarra 18.05.18, available here Archived 2018-08-22 at the Wayback Machine. Slightly different composition of the executive is given in Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Valencia 2009, p. 191

- Montejurra was intended to be sort of a Carlist Calvary, Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo, 1962–1977, Pamplona 1997; ISBN 9788431315641, p. 40

- In memoriam José Ángel Zubiaur Alegre, [in:] Comunión Tradicionalista service 27.03.12, available here Archived 2018-08-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 285

- Mikelarena, Moreno, Urtasun, Bernad, Aranaz, Ibáñez 2018

- according to his own recollections in 1943 Zubiaur lived in Pamplona, Correa Ruiz 2011

- Manuel Martorell Pérez, Carlos Hugo frente a Juan Carlos. La solución federal para España que Franco rechazó, Madrid 2014, ISBN 9788477682653, p. 112

- Zubiaur Alegre, Jose Angel entry, [in:] Aunemendi Eusko Entziklopedia online, available here

- In memoriam José Ángel Zubiaur Alegre, [in:] Comunión Tradicionalista service 27.03.12, available here Archived 2018-08-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Ferrer Hortet, Puga Garcia 2015

- Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 341

- Don Jose Angel Zubiaur Alegre: un político Carlista, [in:] Navarra Confidencial 25.03.2012, available here

- García Riol 2015, p. 231

- for details see Maria del Mar Larazza Micheltorena, Alvaro Baraibar Etxeberria, La Navarra sotto il Franchismo: la lotta per il controllo provinciale tra i governatori civili e la Diputacion Foral (1945–1955), [in:] Nazioni e Regioni, Bari 2013, pp. 101–120

- Aurora Villanueva Martínez, Organizacion, actividad y bases del carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo [in:] Geronimo de Uztariz 19 (2003), p. 112

- this is e.g. the case of Larraza Micheltorena, Baraibar Etxeberria 2013

- José María Jimeno Jurío, La diputación de Navarra, el Euskera y Euskaltzaindia (1949–1952), [in:] Fontes linguae vasconum: Studia et documenta 28/73 (1996), p. 510

- "teniendo en cuenta lo que es y ha significado en Navarra la lengua vasca, dentro de la más fervorosa concepción españolista", Jimeno Jurío 1996, p. 511

- Jimeno Jurío 1996, p. 512

- García Riol 2015, p. 231

- Zubiaur Alegre, Jose Angel entry, [in:] Aunemendi Eusko Entziklopedia online, available here

- Martorell Pérez 2009, pp. 344-345

- Patxi Mendiburu, Martorell: ¿el Carlismo, franquista? ¡Tururú!, [in:] Patximendiburu blog service 19.01.2017, available here

- Mendiburu 2017

- García Riol 2015, p. 231; most detailed account of the El Fuerista episode in José-Ángel Zubiaur Carreño, El Fuerista. Órgano antiborreguil 1-4, [in:] Cabos sueltos y retales de la Historia reciente blog, available here

- Josep Miralles Climent, La rebeldía carlista. Memoria de una represión silenciada: Enfrentamientos, marginación y persecución durante la primera mitad del régimen franquista (1936–1955), Madrid 2018, ISBN 9788416558711, p. 351

- even though there were only 5 issues of El Fuerista published and each issue was printed in 500-3,000 copies, José-Ángel Zubiaur Carreño, "El Fuerista. Órgano antiborreguil" (2), [in:] Cabos sueltos y retales de la Historia reciente blog 31.03.17, available here

- Zubiaur practiced as a lawyer and was member of the Pamplona Colegio de Abogados, see El MICAP festeja a su patrona, [in:] MICAP service 17.12.12, available here

- Solidaridad Obrera 30.09.54, available here, Solidaridad Obrera 28.10.54, available here, Miralles Climent 2018, p. 404

- in the early 1950s Zubiaur exchanged letters with the claimant Don Javier, Villanueva Martínez 2003, p. 112

- a 1953 proposal by Astráin, who suggested that a Navarrese secretariado be composed of Zubiaur, Gambra, Ignacio Tapia and José Jaurrieta, Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El papel del carlismo navarro en el inicio de la fragmentación definitiva de la comunión tradicionalista (1957–1960), [in:] Príncipe de Viana 72 (2011), p. 395

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El final de una ilusión. Auge y declive del tradicionalismo carlista (1957–1967), Madrid 2016, ISBN 9788416558407, p. 36

- Javier Lavardín, Historia del ultimo pretendiente a la corona de España, Paris 1976 , p. 40

- Martorell Pérez 2014, p. 183

- Martorell Pérez 2014, pp. 112-113

- Vázquez de Prada 2011, p. 402

- Martorell Pérez 2014, p. 85

- Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 65

- Lavardín 1976, p. 74

- Lavardín 1976, p. 127

- Zubiaur spoke at Montejurra in the 1950s and in 1962, 63, 64, 66 and 69, Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 302; by many Montejurra attendants he was remembered as one of key speakers, Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El proceso de secularización de las fiestas carlistas, [in:] Zainak. Cuadernos de Antropología-Etnografía, 26 (2004), p. 796

- Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 134

- e.g. in Durango, Martorell Pérez 2014, p. 138, in Bilbao, Los fueros como expresión de libertades y raíz de España, [in:] Carlismo Galicia service 02.05.15, available here, or in Valencia, Martorell Pérez 2014, p. 140

- Jeremy MacClancy, The Decline of Carlism, Reno 2000, ISBN 978-0874173444, pp. 173, 305

- Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 162

- throughout the 1960s he frequently published vehemently anti-Juanista pieces in the unofficial Navarrese Carlist press outpost, El Pensamiento Navarro, see e.g. Lavardín 1976, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 471, Ramón María Rodón Guinjoan, Invierno, primavera y otoño del carlismo (1939–1976) [PhD thesis Universitat Abat Oliba CEU], Barcelona 2015, p. 265

- e.g. in 1963 Zubiaur greeted Pacem in terris as endorsement of Spanish self, which he understood as "la unidad católica y la pervivencia foral", Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 42

- e.g. in 1966 Zubiaur was enthusiastic about questionnaires distributed among the Carlists during the Congress at Valle de los Caidos; he claimed that they will "help to forge our political direction", Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 98

- "no habría programa carlista, porque ... son una manifestación de la personalidad humana y el Carlismo se esienta en lo que siempre fue fundamento del Derecho Público cristiano: en Dios y en el hombre", Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 43. In 1966 he claimed that Carlism was "afirmación rotunda de la personalidad humana", Martorell Pérez 2014, p. 221. In 1969 at Montejurra he declared that "lo fundamental del programa carlista era el respeto a la dignidad del hombre", and that "la verdadera solución que presenta el carlismo es la del equlibrio de la persona humana", Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 194

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, La reorganización del carlismo vasco en los sesenta: entre la pasividad y el "separatismo", [in:] Vasconia. Cuadernos de Historia-Geografía 38 (2012), pp. 1132, 1135

- Don Jose Angel Zubiaur Alegre: un político Carlista, [in:] Navarra Confidencial 25.03.2012, available here

- Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 278

- in 1964 Zubiaur lamented to Fal that Carlism lacked structures, that the movement existed from rally to rally, from Montejurra to Quintillo, but that there was nothing in-between. He also praised magnificent work of the princes, Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 237. In 1965 he kept complaining to Fal that about lack or operational efficiency, noting that "tenemos todo, menos eso que en el orden operativo es muy importante", Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 84

- Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 99

- Lavardín 1976, p. 157

- Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, pp. 91-92

- Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, pp. 99-100

- in 1966 he was considered "hombre emblematico del Carlismo", Rodón Guinjoan 2015, p. 322

- Diario de Burgos 17.10.67, available here

- out of 201,000 voters eligible and out of 103,000 votes, Zubiaur got 45,000 votes, see the official Cortes service, available here

- Rodón Guinjoan 2015, p. 385

- Hoja Oficial de Lunes 27.11.67, available here

- Diario de Burgos 07.01.68, available here

- Diario de Burgos 20.12.67, available here

- Diario de Burgos 24.01.68, available catahere

- Diario de Burgos 10.02.68, available here

- Diario de Burgos 20.02.68, available here, Diario de Burgos 21.02.68, available here

- according to some sources "Cortes Transhumantes" emerged as a response to bullying on part of Carrero Blanco, see Josep Miralles Climent, El carlismo militante (1965–1980). Del tradicionalismo al socialismo autogestionario [PhD thesis Universidad Jaume I], Castellón 2015, pp. 68-69

- Martorell Pérez 2014, pp. 250-251

- Mendiburu 2017

- Miralles Climent 2015, p. 70

- Diario de Burgos 18.09.70, available here

- he had no illusions about the prospects of success. When prompted by a government man Zubiaur responded that "colaborar no es decir a todo amén" Martorell Pérez 2014, p. 252, see also T.A., Colaborar no es decir a todo amén (Zubiaur), [in:] Montejurra 35 (1968), p. 14

- Hoja Oficial de La Provincia de Barcelona 08.04.68, available here

- Martorell Pérez 2014, p. 235

- Mediterraneo 01.03.69, available here, Lavardín 1976, p. 285, Angel Garrorena Morales, Autoritarismo y control parlamentario en las Cortes de Franco, Madrid 1977, ISBN 8460008355, pp. 147-150, 261, García Riol 2015, p. 231

- ABC 23.07.69, available here

- Diario de Burgos 06.12.69, available here, España Republicana 15.12.69, available here

- Miralles Climent 2015, p. 72

- Mediterraneo 09.04.70, available here

- Mediterraneo 29.10.69, available here

- Mediterraneo 26.11.70, available here

- Diario de Burgos 02.12.70, available here

- Víctor Manuel Arbeloa, Jesús María Fuente, Vida y asesinato de Tomás Caballero, Llanera 2006, ISBN 8484591425, p. 106

- Mediterraneo 21.10.70, available here; a later observer noted that Zubiar and the others "hacian también la guerra al franquismo, pero desde las instituciones", ABC 26.11.92, available here

- Mediterraneo 19.07.71, available here, Diario de Burgos 21.07.71, available here

- Diario de Burgos 10.03.71, available here

- some scholars claim even that Zubiaur was "uno de los hombres fuertes de Don Javier en Navarra y despues tambien de Carlos Hugo hasta su escision ideologica", Víctor Javier Ibáñez, Una resistencia olvidada. Tradicionalistas mártires del terrorismo, s.l. 2017, p. 201

- Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, pp. 131-132; Zubiaur got the number of votes far exceeding these collected by other appointees, Saenz-Díez, Fal Macias, and d'Ors, Rodón Guinjoan 2015, p. 394

- Miralles Climent 2015, p. 68

- be it across Navarre, see Martorell Pérez 2014, p. 254, or across Catalonia, see Hoja Oficial de la Provincia de Barcelona 08.04.68, available here

- Don Jose Angel Zubiaur Alegre: un político Carlista, [in:] Navarra Confidencial 25.03.2012, available here

- Rodón Guinjoan 2015, p. 439

- Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 193

- Mediterraneo 14.05.69, available here; Zubiaur protested, see Mediterraneo 04.07.69, available here, Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 334. Following threat of seizure of his property Zubiaur had to pay the fine, though with some anonymous aid

- José-Ángel Zubiaur Alegre, José-Ángel Zubiaur Carreño, Elecciones a Procuradores familiares en Navarra en 1971, [in:] Aportes 27/79 (2012), p. 157

- Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 204, Miralles Climent 2015, p. 265

- Miralles Climent 2015, p. 265

- in the late 1960s El Pensamiento Navarro assumed a progressist course upon nomination of its new editor-in-chief, Javier María Pascual Ibañez. In 1970 the Traditionalist Baleztena family, owners of most shares in the company which ran Pensamiento, staged a counter-offensive and fired Pascual. The Progressists mounted a propaganda counter-strike; as part of it, many prominent Carlists resigned their Pensamiento subscriptions. Zubiaur was one of them, Montejurra 53 (1970), p. 15

- Informacion Española 01.02.71, available here

- Rodón Guinjoan 2015, p. 512

- Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 472

- at least until the early 1970s; some scholars suggest that Zubiaur was up to a point following the new line of Carlos Hugo, Ibáñez 2017, p. 201. In a 1968 press interview when asked "¿Existen discrepancias políticas dentro el Carlismo?" he responded: "Si se refiera a un secesionismo, desde luego no. En lo fundamental hay unidad de criterio, total y absoluto". When asked "¿Hasta qué punto el 'neo Carlismo' ha absorbido algunas ideas del neo Liberalismo?" Zubiaur responded: "De ninguna forma. Creo, por el contrario, que hay jóvenes dentro del Carlismo que tienen ciertas ideas also avanzadas, pero, como le digo anteriormente, en lo fundamental estamos todos de acuerdo", Diario de Mallorca 11.04.68, quoted after Montejurra 36 (1968), p. 22

- when in Lignieres in 1970 María Teresa Borbón-Parma tried to explain to Zubiaur the difference between bourgeoisie parties and mass parties: in the former deputies were free to act based on false individualist principles, in the former they were expected to carry out the will of the people, Zubiaur Alegre, Zubiaur Carreño 2012, p. 157

- he was pressed also by the party secretary general, José María Zavala Castella, see Zubiaur Alegre, Zubiaur Carreño 2012, pp. 160-162

- as Zubiaur and Goñi had already endorsed some candidates and according to official electoral legislation they were not legally entitled to endorse more, they contacted friendly ex-procuradores from other parties to get necessary endorsement for Mariano Zufia Urrizalqui and Perez-Nievas Abascal, Zubiaur Alegre, Zubiaur Carreño 2012, p. 164. Both Zufia and Perez-Nievas failed to get elected

- Miralles Climent 2015, p. 233

- e.g. when speaking at Círculo Aparisi in Valencia in 1973, García Riol 2015, pp. 341-342

- Diario de Burgos 14.02.75, available here

- García Riol 2015, pp. 250, 541, Rodón Guinjoan 2015, p. 589

- Mediterraneo 02.03.75, available here

- Arbeloa, Fuente 2006, pp. 461-462

- Ibáñez 2017, p. 202

- The key personalities listed behind FNI are Víctor Manuel Arbeloa, Ignacio Irazoqui, Tomás Caballero and Zubiaur, see Don Jose Angel Zubiaur Alegre: un político Carlista, [in:] Navarra Confidencial 25.03.2012, available here, Arbeloa, Fuente 2006, p. 463

- Arbeloa, Fuente 2006, p. 466

- Arbeloa, Fuente 2006, p. 475

- "viudo del Carlismo, que trata de buscar a alguien que haga de madre de sus hijos", quoted after García Riol 2015, pp. 353-4

- in 1977 Zubiaur co-signed an FNI declaration which read: "como navarros que somos, tronco y raíz de Euskalerría, queremos vivir en sólida vinculación con el resto del País Vasco, en la forma que el pueblo navarro elija", Jose Mari Esparza, Mapas para una Nación: Euskal Herria en la cartografía y en los testimonios históricos, Tafalla 2011, ISBN 9788481366204, p. 212

- Martorell Pérez 2009, pp. 481-482, Fermín Pérez-Nievas Borderas, Contra viento y marea. Historia de la evolución ideológica del carlismo a través de dos siglos de lucha, Pamplona 1999, ISBN 9788460589327, p. 218

- Diario de Burgos 22.06.78, available here

- already in the 1940s Zubiaur kept hailing separate legal regional establishmens, see e.g. his article Concepto de tradición, [in:] El Pensamiento Navarro 28.11.43. During mid-Francoism he was already a recognized expert on fueros. In 1959 in Burgos he delivered a lecture on Iinsitutución, función y fuero, in 1960 he spoke about Los fueros como libertades concretas, Diario de Burgos 03.03.60, available here; in the same spirit he lectured in Bilbao in 1965, Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 43

- see printed version of his 1965 fuerista lecture, available here Archived 2018-08-22 at the Wayback Machine

- see especially Curso de Derecho Foral Navarro. Derecho Público (1959) and Los fueros como expresión de libertades y raíz de España (1965), García Riol 2015, p. 231

- Fernando Mikelarena Peña, Los posicionamientos de la Diputación Foral de Navarra y de la derecha navarrista entre 1976 y 1978 en relación al debate preautonómico, [in:] Iura vasconiae: revista de derecho histórico y autonómico de Vasconia 11 (2014), pp. 191-195

- the founders of UPN are listed as Jesús Aizpún, José Angel Zubiaur, María Isabel Beriáin, Ignacio Javier Gómara, Ramón Echeverría, Feliciano Aramendía and Javier Chourraut, Jaime Ignacio del Burgo, La epopeya de la foralidad vasca y navarra, Pamplona 2016, ISBN 9788494503702, p. 143

- Oscar Barberà Aresté, Los orígenes de la Unión del Pueblo Navarro (1979–1991), [in:] Papers: revista de sociología 92 (2009), p. 146

- Don Jose Angel Zubiaur Alegre: un político Carlista, [in:] Navarra Confidencial 25.03.2012, available here

- he gathered 28,000 votes, Union del Pueblo Navarro entry, [in:] Gran Enciclopedia Navarra online, available here

- in the 1979 general elections UPN obtained 11,2% of votes, in 1979 Navarrese elections the party gathered 16,1%, Barberà Aresté 2009, p. 151

- Barberà Aresté 2009, p. 149

- Don Jose Angel Zubiaur Alegre: un político Carlista, [in:] Navarra Confidencial 25.03.2012, available here

- Barberà Aresté 2009, p. 149

- Mediterraneo 29.05.83, available here

- Don Jose Angel Zubiaur Alegre: un político Carlista, [in:] Navarra Confidencial 25.03.2012, available here

- see Elecciones al Parlamento de Navarra service, available here

- Barberà Aresté 2009, p. 156

- Mediterraneo 01.09.83, available here, El País 07.02.84, available here

- full sentence of the court ruling is available at Universiad Nacional de Educación a Distancia service, available here

- Mediterraneo 07.02.84, available here

- Don Jose Angel Zubiaur Alegre: un político Carlista, [in:] Navarra Confidencial 25.03.2012, available here

- Boletin Oficial del Parlamento de Navarra, 04.03.86, available here

- Más de 600 personas participan en el acto de conmemoración del 25. aniversario de la creación de la Universidád Pública de Navarra, [in:] unavarra service 27.04.12, available here

- Román Felones Morrás, La Universidad Pública de Navarra: génesis y proceso de creación, [in:] unavarra service, available here, p. 9

- García Riol 2015, p. 231

- ABC 13.09.87, available here

- ABC 11.02.91, available here

- Union del Pueblo Navarro entry, [in:] Gran Enciclopedia Navarra online, available here

- ABC 07.02.93, available here

- ABC 08.02.93, available here

- José Fermin Garralda, Funeral por don José Ángel Zubiaur Alegre, [in:] Tradición Viva service 24.03.12, available here

- Fermin Garralda 2012

- titled Apuntes de mi vida política and completed in 1995, Zubiaur's memoirs remain unedited, José-Ángel Zubiaur Carreño, "El Fuerista. Órgano antiborreguil" (1), [in:] Cabos sueltos y retales de la Historia reciente blog 31.03.17, available here

- Ferrer Hortet, Puga Garcia 2015. Zubiaur noted that the Carlism of his youth "habia evolucionado, tanto en la mente de sus pensadores como en el de sus Reyes. Se había desarollado, y mucho, la vieja tradición, al amparo de las ideas religiosas y de la idiosincrasia del pueblo, amante de las libertades concretas", and confessed that he "deseo, ya que el carlismo nu pueda ser vivido, que con este libro, al menos, pueda ser recordado"

- Rodón Guinjoan 2015, p. 481

- Lavardín 1976, p. 289

- Zubiaur Alegre, Zubiaur Carreño 2012, p. 167

- Correa Ruiz 2011

Further reading

- Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo, 1962–1977, Pamplona 1997; ISBN 9788431315641

- Daniel Jesús García Riol, La resistencia tradicionalista a la renovación ideológica del carlismo (1965–1973) [PhD thesis UNED], Madrid 2015

- Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis UNED], Valencia 2009

- Josep Miralles Climent, El carlismo militante (1965–1980). Del tradicionalismo al socialismo autogestionario [PhD thesis Universidad Jaume I], Castellón 2015

- Josep Miralles Climent, La rebeldía carlista. Memoria de una represión silenciada: Enfrentamientos, marginación y persecución durante la primera mitad del régimen franquista (1936–1955), Madrid 2018, ISBN 9788416558711

- Ramón María Rodón Guinjoan, Invierno, primavera y otoño del carlismo (1939–1976) [PhD thesis Universitat Abat Oliba CEU], Barcelona 2015

- José-Ángel Zubiaur Alegre, José-Ángel Zubiaur Carreño, Elecciones a Procuradores familiares en Navarra en 1971, [in:] Aportes 27/79 (2012), pp. 147–167

_-_Fondo_Mar%C3%ADn-Kutxa_Fototeka.jpg.webp)