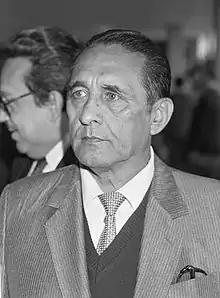

José Napoleón Duarte

José Napoleón Duarte Fuentes (23 November 1925 – 23 February 1990) was a Salvadoran politician who served as President of El Salvador from 1 June 1984 to 1 June 1989. He was mayor of San Salvador before running for president in 1972. He lost, but the election is widely viewed as fraudulent.[1] Following a coup d'état in 1979, Duarte led the subsequent civil-military Junta from 1980 to 1982. He was then elected president in 1984, defeating ARENA party leader Roberto D'Aubuisson.

José Napoleón Duarte | |

|---|---|

| |

| 36th President of El Salvador | |

| In office 1 June 1984 – 1 June 1989 | |

| Vice President | Rodolfo Castillo |

| Preceded by | Álvaro Magaña |

| Succeeded by | Alfredo Cristiani |

| President of the Revolutionary Government Junta | |

| In office 13 December 1980 – 2 May 1982 | |

| Vice President | Jaime Abdul Gutiérrez |

| Preceded by | Position established (Jaime Abdul Gutiérrez as chairman) |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished (Álvaro Magaña as president of El Salvador) |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 3 March 1980 – 1982 | |

| Preceded by | Héctor Miguel Hirezi |

| Succeeded by | Fidel Chávez Mena |

| Mayor of San Salvador | |

| In office March 1964 – 1970 | |

| Succeeded by | Carlos Rebollo |

| Personal details | |

| Born | José Napoléon Duarte Fuentes 23 November 1925 Santa Ana, El Salvador |

| Died | 23 February 1990 (aged 64) San Salvador, El Salvador |

| Cause of death | Stomach cancer |

| Resting place | Cementerio Jardines del Recuerdo San Salvador, El Salvador |

| Political party | Christian Democratic Party |

| Spouse | Inés Durán de Duarte (died 2011) |

| Education | Liceo Salvadoreño |

| Alma mater | |

| Signature |  |

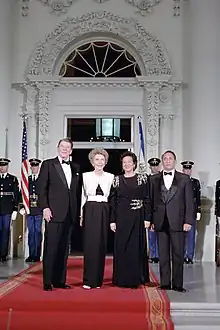

Supported by the Reagan Administration and the Central Intelligence Agency, his time in office occurred during the worst years of the Salvadoran Civil War which saw numerous abuses and massacres of the civilian population by the Salvadoran security forces and the death squads linked to them.[2][3][4]

Early life

Duarte was born in Santa Ana in the department of the same name. While he was studying at Liceo Salvadoreño in May 1944, he took part in the protests that brought down the twelve-year-old regime of then-President General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez. Other military regimes followed, and in 1945 he crossed the border into Guatemala to join the opposition in exile. Although he spoke no English at the time, his father enrolled him in the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, United States. In 1948, having worked doing dishes and laundry in order to support himself through his studies, he graduated with a degree in engineering before returning to an El Salvador uncomfortably transitioning to a democracy. He married his childhood sweetheart, Maria Inés Durán, with whom he had 6 children: Inés Guadalupe, Alejandro, Napoleón, María Eugenia, María Elena, and Ana Lorena. Duarte got a job in his father-in-law's construction firm and, at the same time, began teaching.

Political career

Mayor of San Salvador

In 1960, he became a founding member and Secretary General of the Christian Democratic Party (PDC), which searched for a middle ground between the extreme right and the extreme left. Even as part of the United Democratic Party (PUD), the PDC failed to gain a seat in that year's National Congress elections. After boycotting the 1962 presidential elections, Duarte became Mayor of San Salvador in March 1964. He initiated the Adult Evening Schools helping a lot of adult workers to become technicians and also get high school diplomas. He supported emerging sectors of the economy and some redistribution of wealth. Duarte easily won the next two elections for mayor in March 1966 and March 1968.

After leaving office in 1970, he set up his own estate agency until he ran in the February 20, 1972 presidential election under a political grouping called the United National Opposition (UNO). He lost to Arturo Armando Molina in an election that was widely viewed as fraudulent, with Molina declared the winner even though Duarte was said to have received a majority of the votes; poll watchers claimed the real vote tally was 327,000 for Duarte and 318,000 for Molina.[5][1][6]

On 25 March 1972, a coup d'état was attempted by left-wing military officers who supported Duarte. The coup was suppressed and Duarte was arrested. He was subjected to torture. He was condemned to death for high treason, but international pressure forced Molina to grant him exile, which he obtained in Venezuela. Duarte got a job as an engineering advisor and became involved as a private investor in various construction projects. He was also given posts in the international Christian Democratic movement. In 1974, he returned to El Salvador, where he was promptly arrested and returned to Venezuela.

Junta leader

On 15 October 1979, a Revolutionary Government Junta (JRG) took control of El Salvador, deposing President Carlos Humberto Romero. This is the start of the beginning of a full scale civil war. Duarte returned to El Salvador on March 3, 1980 and joined the Junta, becoming El Salvador's foreign minister.

Just weeks after joining the government, Duarte came to the attention of the U.S. public as spokesperson for the Junta following the assassination of Archbishop Romero on 24 March 1980. As an official source, he promoted a "blame on both sides" apologetic to explain the government's lack of resolve to investigate the assassination.[7]

On 22 December 1980, he became the head of state and of the Junta. The Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) responded by launching an all out attack on the government on January 10, 1981, which resulted in the regime receiving immediate military aid and advisors from the United States of America.

With the arrival of the new US government of Ronald Reagan, Duarte became a symbol for "anti-communist" resistance in Central America although support for the FMLN from the Soviet Union has been questioned by Noam Chomsky.[2]

On 28 March 1982, elections were held to the National Congress in which Duarte's Christian Democratic Party (PDC) party gained 24 of the 60 seats, putting them in opposition against the combined strength of the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) party, which gained 19 seats, and the National Conciliation Party (PNC), which gained 14. On 2 May, he handed over power to Álvaro Magaña, who had been chosen President by the National Congress. During his time at the head of the JRG, Duarte initiated land reform and nationalized certain industries such as sugar as well as denouncing human rights violations by the military and the FMLN alike. However, members of the military and affiliated death squad paramilitaries continued to carry out atrocities against the civilian population during his rule as the head of JRG, under the pretext of eliminating terrorists. The Salvadoran army received financial and material support throughout this period from the CIA, which also trained many of the squads, and arranged for arms supplies from Israel when Congress terminated direct CIA support.[2]

President (1984–1989)

On 25 March 1984, in the 1984 presidential elections, Duarte (running as the PDC candidate), running along with Rodolfo Antonio Castillo Claramount, came in first with 43.4% of the vote. In the second round, on 6 May, he won with 53.6% of the vote against the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) candidate, Roberto D'Aubuisson. The elections were marred by violence between the FMLN and Salvadoran military at and near the polling stations. As both candidates were known to have close links with wartime undemocratic factions, the US government spent approximately US$2 million to support the democratic process and prevent violence at the voting polls. However, some scholars of Central American history have suggested that the CIA was merely ensuring that Duarte, the candidate favored by the US, was elected.[2]

Duarte became president on 1 June. He was determined to end the civil war by "dialogue without arms," and on 15 October 1984, in La Palma, Chalatenango, he met FMLN leaders face to face, which marked the beginning of the end of the civil war. His basic goal, he claimed, was to see the guerrillas disarm and then to demobilize so that their members could be reincorporated into society. He argued that the issues that had caused them to rise up in armed struggle had been or were being resolved.

The FMLN demanded for ARENA to be banned from participating in the political life of the country, which made the dialogue between the two sides difficult. During 1985, Duarte tried to improve the image of the state by banning the Salvadoran Air Force from bombing civilian areas without presidential permission, creating an Investigative Commission to investigate political assassinations, and prosecuting the right-wing death squads that were alleged to be embedded in the state security services. However, that attempt largely failed to influence the excesses of the death squads.

On 31 March, in the 1985 congressional elections, the PDC gained a majority with 33 seats. ARENA's loss of control in the Congress enabled Duarte to achieve his goals more easily. On 10 September 1985, his daughter, Inés Guadalupe Duarte Durán, and her friend, Ana Cecilia Villeda, arrived by car at the gates of a private university in San Salvador. They were followed in a van by two bodyguards assigned to protect them. As the two vehicles came to a stop, other vehicles positioned themselves to block traffic while a number of armed individuals killed the bodyguards and forced the two women into a truck. The two women were taken to a guerrilla camp.

Four days after the incident, the self-styled Pedro Pablo Castillo commando of the FMLN publicly announced that it had been responsible for the abduction of the women. In spite of angering the military, Duarte's family was sent to the United States for its safety, and he began the negotiations for the release of Inés Duarte and Ana Cecilia Villeda.

On 24 October, after several weeks of negotiations in which the Salvadoran church and diplomats from the region acted as mediators in secret talks, Inés Duarte and her friend were released in exchange for 22 political prisoners. The operation also included the release of 25 mayors and local officials abducted by FMLN in exchange for 101 war wounded guerrillas, whom the government allowed to leave the country. The entire process of exchanging prisoners, which took place in various parts of the country, was carried out through the International Committee of the Red Cross.

In a communiqué from the FMLN General Command broadcast by Radio Venceremos on the day Inés Duarte was released, the General Command assumed full responsibility for the operation and described the actions of the commando, including the killing of the bodyguards, as "impeccable". The abduction of Inés Duarte and Ana Cecilia Villeda was widely denounced as a violation of international law.

In 1986, Duarte's tax reform plans, bitterly opposed by ARENA, were judged unconstitutional. In August, he participated in the historic Esquipulas II agreement with other leaders to lay the groundwork for a firm and lasting peace in Central America by outlining the demobilization of the guerrilla groups in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua. On 5 October 1987, a third dialogue began between the government and the FMLN, and on 28 October, Congress passed an amnesty law, just two days after Herbert Anaya, the president of the special United Nations Human Rights Commission for El Salvador, had been assassinated. Anaya's assassination was interpreted by some as a sign of disapproval of the peace process.

Duarte was criticized by the Organization of American States, which demanded a full investigation into Anaya's death. As a result, Duarte offered a reward of $10,000 and asked the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to investigate. The National police arrested a suspect Jorge Alberto Miranda Arevalo, who confessed that he had acted as a lookout for the gang. He said that he was a member of one of the guerrillas groups, "the ERP." He was judged and sentenced to 30 years in prison.

Duarte was increasingly seen as powerless not only between the two opposing forces of left and right but also in terms of the US anticommunist political influence in the region. With corruption scandals, an economy in tatters, rumors of a right-wing coup, and a civil war that did not appear to have a solution, the government became ineffective, unstable, and unable to stop the indiscriminate violence and brutality. In the 20 March 1988 elections, the PDC were soundly beaten by ARENA in a fair election.

In June 1988, Duarte was rushed to a military hospital in Washington, DC, where he was diagnosed with advanced stomach cancer and given between 6 months to a year to live. Both the diagnosis and the prognosis became public knowledge. In spite of having to stay in the United States for surgery and chemotherapy, he refused to resign as president, and he handed power over constitutionally to Alfredo Cristiani in June 1989. He died at 64 in San Salvador on 23 February 1990.

Duarte: My Story

In his autobiography, Duarte wrote: "When the structures and values of Salvadoran society exemplify a democratic system, then the revolution I have worked for will have taken place. This is my dream".[8]

References

- Pace, Eric (24 February 1990). "Jose Napoleon Duarte, Salvadoran Leader In Decade of War and Anguish, Dies at 64". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- Chomsky, Noam (1985). Turning the Tide. Boston, Massachusetts: South End Press. pp. 16–28, 109–27. ISBN 9780896082663.

- Grandin & Joseph, Greg & Gilbert (2010). A century of Revolution. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 3–4, 391.

- Wood, Elizabeth (2003). Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- "El Salvador". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- "CNN Cold War – Profile: Jose Napoleon Duarte Fuentes". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- New York Times, "5,000 in San Salvador Take Part in a March for Murdered Prelate", 27 March 1980.

- Duarte: My Story, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1986 ISBN 0-399-13202-3.

External links

- Biography by CIDOB (in Spanish)

- "Central America Still Gunning for Peace"—Time article about Herbert Sanabria's murder in 1987.