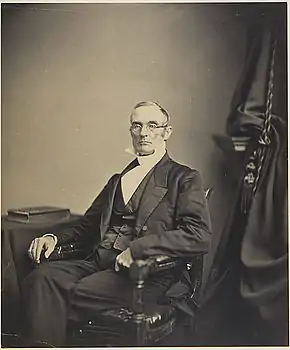

Joshua Leavitt

Rev. Joshua Leavitt (September 8, 1794, Heath, Massachusetts – January 16, 1873, Brooklyn, New York) was an American Congregationalist minister and former lawyer who became a prominent writer, editor and publisher of abolitionist literature. He was also a spokesman for the Liberty Party and a prominent campaigner for cheap postage. Leavitt served as editor of The Emancipator, The New York Independent, The New York Evangelist, and other periodicals. He was the first secretary of the American Temperance Society and co-founder of the New York City Anti-Slavery Society.[1]

Biography

Born in Heath, Massachusetts, in the Berkshires, Leavitt attended Yale College, where he graduated at age twenty. He subsequently studied law and practiced for a time in Putney, Vermont, before matriculating at the Yale Theological Seminary for a three-year course of study. He was subsequently ordained as a Congregational clergyman at Stratford, Connecticut. After four years in Stratford, Rev. Leavitt decamped for New York City, where he first became secretary of the American Seamens' Friend Society, and began his 44-year career as editor of Sailors' Magazine. Thus was Leavitt launched on his career as social reformer, temperance spokesman, editor, abolitionist and religious proselytizer.[2]

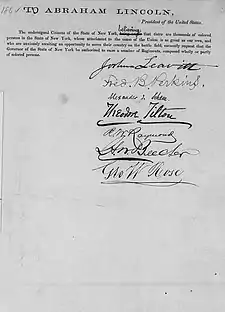

Leavitt was heavily involved in a series of high-profile anti-slavery cases, including the escape of the slave Basil Dorsey from Maryland into Massachusetts (Leavitt aided Dorsey's passage northward, and members of the extended Leavitt family helped shelter Dorsey in Massachusetts), as well as the La Amistad case, in which enslaved Africans on a Spanish ship rebelled and took control.[3] Leavitt played a pivotal role in the Amistad events, when on September 4, 1839, he, Lewis Tappan, and Simeon Jocelyn formed the Amistad Committee to raise funds for the defense of the Amistad captives.[4]

One of Leavitt's major accomplishments was helping to provide the intellectual underpinnings of the abolitionist argument through his writing and publishing. In 1841, for instance, Leavitt published his "Financial Power of Slavery", a compelling document which argued that the South was draining the national economy through its reliance on slavery.

The Christian Lyre

Leavitt published The Christian Lyre in 1830,[5] the "first American tunebook to take the form of a modern hymnal, with music for every hymn (melody and bass only) and the multistanza hymns printed in full, under or beside the music". It later became one of the standard tunebooks used in the 1830s New England Revivalism movement.[6]

Family

Rev. Joshua Leavitt came from a long line of religious figures.[7] His father was Col. Roger Leavitt, a wealthy landowner and Massachusetts legislator, and his mother Chloe (Maxwell) Leavitt. His grandfather was the Congregational minister Rev. Jonathan Leavitt, a 1758 graduate of Yale and pastor of Charlemont, Massachusetts.[8][9] The Leavitt family had ties to religious institutions since Joshua Leavitt's ancestor John Leavitt served as founding deacon of Old Ship Church in Hingham, Massachusetts, and his ancestor Rev. Thomas Hooker had left the Massachusetts Bay Colony to found the state of Connecticut.[10]

Rev. Joshua Leavitt's son William was a Congregational minister in Hudson, New York. Aside from Rev. Joshua Leavitt, other members of the Leavitt family were prominent abolitionists. The National Park service lists two Leavitt family properties in upstate Massachusetts – the Hart and Mary Leavitt House,[11] as well as the Roger Hooker and Keziah Leavitt House – on its National Underground Railroad historic sites tour.[12] The entire extended family of Rev. Joshua Leavitt can be considered ardent – and active – abolitionist sympathizers.[13]

Notes

- "Leavitt, Joshua". Archived from the original on 2006-09-07. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- A History of the Churches and Ministers, and of Franklin Association, Theophilus Packard, Boston, 1854

- The Amistad Case (1839–1840), American History told by Contemporaries, Joshua Leavitt, The Macmillan Company, New York, 1901

- Amistad, Timeline of Events, National Park Service, nps.org

- Scan at https://archive.org/details/christianlyre00leav/

- Crawford, p. 169

- Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College, Franklin Bowditch Dexter, Vol. II, Henry Holt & Co., New York, 1896

- Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College, Vol. VI, Yale University Press, New Haven, Ct., 1912

- Roger Hooker Leavitt is interred at the Leavitt cemetery in Charlemont, Massachusetts

- The Descendants of Rev. Thomas Hooker, Hartford, Connecticut, Edward Hooker, Margaret Huntington Hooker, 1909

- Hart and Mary Leavitt House, Charlemont, Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, National Park Service, nps.gov Archived 2011-05-24 at the Wayback Machine

- National Underground Railroad Network, The National Park Service, nps.gov

- Roger Hooker and Keziah Leavitt House, Charlemont, Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, National Park Service, nps.gov Archived 2011-03-05 at the Wayback Machine

References

- Crawford, Richard (2001). America's Musical Life: A History. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04810-1.

- Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

Further reading

- The Road to Freedom: Anti-Slavery Activity in Greenfield, Greenfield Human Rights Commission, the Greenfield Historical Commission, starrcenter.washcoll.edu

- The Amistad Case, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

- Joshua Leavitt, Evangelical Abolitionist, Hugh Davis, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, La., 1990, ISBN 0-8071-1521-5

External links

- Portrait of Joshua Leavitt, Massachusetts Historical Society

- Works by Joshua Leavitt at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Joshua Leavitt at Internet Archive

- Finance of Cheap Postage, Joshua Leavitt, Secretary of the Boston Cheap Postage Association, Boston, 1849

- The Christian Lyre, Joshua Leavitt, New York, 1833

- The Monroe Doctrine, Joshua Leavitt, New York, 1863

- Easy Lessons in Reading for the Use of the Younger Classes, Joshua Leavitt, Keene, New Hampshire, 1830

- The Amistad Case, The National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.