Josiah Gregg

Josiah Gregg (19 July 1806 – 25 February 1850) was an American merchant, explorer, naturalist, and author of Commerce of the Prairies, about the American Southwest and parts of northern Mexico. He collected many previously undescribed plants on his merchant trips and during the Mexican–American War, for which he has often been credited in botanical nomenclature. After the war he went to California, where he reportedly died of a fall from his mount due to starvation near Clear Lake on 25 February 1850, following a cross-country expedition which fixed the location of Humboldt Bay.

Josiah Gregg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 19, 1806 |

| Died | February 25, 1850 (aged 43) |

| Occupation(s) | Merchant, explorer, naturalist, and author |

Early years

Josiah Gregg was born on July 19, 1806, in Overton County, Tennessee, the youngest son of seven children of Harmon and Susannah (Smelser) Gregg.[1][2] Six years later his family moved to Howard County, Missouri.[2] At age 18, Gregg was a schoolteacher in Liberty, Missouri until moving again with his family to Independence a year later in 1825.[2] In Liberty, he studied law and surveying until his health declined from "consumption and chronic dyspepsia" in 1830.[2]

Because of his failing health, Gregg followed his doctor's recommendation and traveled alongside a merchant caravan to Santa Fe, New Mexico on a trail beginning at Van Buren, Arkansas, in 1831.[1] Once he arrived in what would later become the New Mexico Territory, Gregg worked as a bookkeeper for Jesse Sutton, one of the merchants of the caravan, before returning to Missouri in fall 1833, but by spring he was back on the road to Santa Fe, this time as wagonmaster of a caravan and Sutton's business partner.[2] Gregg brought the first printing press to New Mexico in 1834, selling it to Ramon Abreu in Santa Fe, where it was used to print the territory's first newspaper.[3]

By 1840, Gregg had learned Spanish, crossed the plains between Missouri and Santa Fe four times, traveled the Chihuahua Trail into Mexico, and become a successful businessman.[2] On his last trip from Santa Fe eastward, he decided to take a more southerly route across to the Mississippi River. Leaving Santa Fe on 25 February 1840, he was accompanied by 28 wagons, 47 men, 200 mules and 300 sheep and goats.[2] In March the caravan was attacked by Pawnee near Trujillo Creek in Oldham County, Texas, and a storm scattered most of his stock across the Llano Estacado, but the group continued eastward through Indian Territory to Fort Smith and Van Buren.[2] In the early 1840s, Gregg briefly lived in Shreveport, Louisiana.[4]

Only a few months later, he traveled through the Oklahoma Territory as far west as Cache Creek in the Comanche territory.[2] During 1841 and 1842, Gregg's travels took him through Texas and up the Red River valley, and on a second trip he went from Galveston to Austin and back through Nacogdoches to Arkansas.[2] Along the way he took notes of the natural history and human culture of the places he visited, and profitably sold mules to the Republic of Texas.[2] He briefly settled as partner in a general store with his brother John and George Pickett in Van Buren.[2] He began to work his travel notes into a manuscript and visited New York in the summer of 1843 to find a publisher.[2] In New York he devoted himself to working on his book while staying at the Franklin Hotel at the corner of Broadway and Cortland Streets.[5]

Commerce of the Prairies

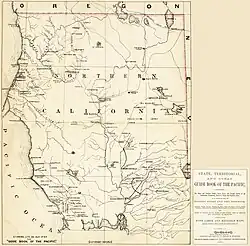

Gregg's book Commerce of the Prairies, published in two volumes in 1844, is an account of his time spent as a trader on the Santa Fe Trail from 1831 to 1840 and includes commentary on the geography, botany, geology, and culture of New Mexico.[6] Gregg wrote about local people and described Indian culture and artifacts. The book was an immediate success and established Gregg's literary reputation.[7] It went through several editions, sold a large number in England, and was translated into French and German.[2] The map he produced of the Santa Fe Trail and surrounding plains was the most detailed up to that time, and his suggestions of where the Red River headwaters might be found inspired the journey of Randolph B. Marcy and George B. McClellan in 1852.[2]

Mexican–American War

In the fall of 1845, Gregg began studying medicine at the University of Louisville School of Medicine. He graduated two semesters later on March 9, 1846.[1] By then, Gregg had learned to make daguerrotypes, and had become friends with artist and daguerrotypist John Mix Stanley,[1] who was on Samuel C. Owens' wagon train with Gregg.[8] As part of his equipment for his trip to Santa Fe with the Owens wagon train were special-sized plates for his sixth-plate camera, probably delivered to him by naturalist Friedrich Adolph Wislizenus.[1] The fate of the camera and any images he made is unknown.[1] Gregg left Owens' caravan at the outbreak of the Mexican–American War when he joined General John E. Wool's Arkansas Volunteers as an unofficial news correspondent and interpreter.[2][7][9] In this capacity, he traveled through Chihuahua.[9]

After the war

Gregg had previously planned to enter business with Susan Shelby Magoffin's husband Samuel, so he left his effects and collections in Saltillo and traveled to the east in 1847 to buy merchandise; upon arrival he received a message from Magoffin, who had changed his mind.[10] Gregg traveled to Washington, D.C., where he was unimpressed after meeting President James K. Polk, and took a series of steamships down the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico, then up the Rio Grande and back to Saltillo at the end of 1847. Through the spring of 1848 he actively practiced medicine for the first time since earning his degree.[10] He complained that his medical partner, Dr. G. M. Prevost, was disorganized and "in love" with a 13-year-old girl.[10]

Plant collector

Several plant species native to the Southwestern United States and Mexico bear the species patronym greggii to honor Gregg's contributions to botany, including Ceanothus greggii, the desert ceanothus, which he collected at the site of the Battle of Buena Vista in 1847.[7] He found and collected other plants, many of which were previously unknown, on a trip to Mexico between 1848 and 1849 with Wislizenus. He sent the specimens to his friend, botanist George Engelmann,[10] in St. Louis, Missouri, to be identified.[2][7][11]

Gold Rush and Humboldt Bay

In 1849, Gregg joined the California Gold Rush by sailing from Mazatlán to San Francisco, eating canned food for the first time and remarking in a letter that he liked it.[12] He left field notes with his former partner Jesse Sutton and gave Sutton instructions what to do with them if he did not return from what might turn out to be his last trip.[13] Shortly thereafter he visited placer mines on the Trinity River.[7]

On November 5, 1849, a party of ill-provisioned miners led by Gregg left Rich Bar, a mining camp on the Trinity River north of Helena intending to find "Trinity Bay" by crossing unknown territory and following the line of latitude westward.[14] The roster of the party was: Gregg; Thomas Seabring of Ottawa, Illinois; David A. Buck of New York; J. B. Truesdale of Oregon; Charles C. Southard of Boston; Isaac Wilson of Missouri; Lewis Keysor Wood of Kentucky; and James Van Duzen.[14][15]

They had been told by Indians that the Pacific Ocean was an eight-day journey, so they provisioned for ten days' rations.[14] A few days past the start, David A. Buck discovered the South Fork Trinity River, where the party encountered a group of Indians who fled from them.[14] The party took smoked salmon from the Indian rancheria and set up camp only a short distance away.[14] That evening eighty warriors arrived at the Gregg party camp, but only a discussion followed; the Indians warned them against following the Trinity to the sea, and said to go westward and leave the river,[14] a trail which later became part of California State Route 299.[16] The party instead followed the river until it became impassable, then went west.[16] By November 13, the provisions were gone and the party began to subsist on deer and smoked game,[14] averaging 7 miles (11 km) a day until they got to the redwood forests, after which they averaged only about 2 miles (3.2 km) a day.[16] About six weeks after they started,[17] they emerged from the redwood forests and saw the ocean at the mouth of a watercourse which they called the Little River.[14] After exploring slightly to the north, they turned south along the coast and camped at Trinidad.[14]

Leaving Trinidad, they crossed a large river, but the fed-up members of the exploring party did not wish to wait for Gregg to determine the latitude of the mouth, and so pushed off without him.[14] When he caught up with the group, his temper flared, and they named the river Mad River due to the outburst.[14]

On December 20, 1849, David A. Buck was the first to discover what this party named "Trinity Bay", which a few months later became known as Humboldt Bay.[17] The party walked around the bay and past the site of present-day Arcata, had a Christmas meal of elk meat near the Elk River,[18] and passed through present-day Eureka on 26 December.[14] They reached the bay at a point which would later be both the location of Fort Humboldt and the townsite of Bucksport, named after David A. Buck, the discoverer of the bay.[14]

Three days later, they came upon and named the Eel River, the "Eel" in the name being a misnomer for the Pacific lamprey which local Indians had caught and shared with the party at about where the Van Duzen River, named after James Van Duzen, joins the Eel.[14]

Shortly thereafter, the party argued again about the best way to get back to San Francisco.[14] About 20 miles (32 km) from the coast on the Eel River, the group split in two: Seabring, Buck, Wilson and Wood followed the Eel River, while Gregg, Van Duzen, Southard and Truesdale went to the coast.[17] L.K. Wood was permanently crippled by a grizzly bear while stuck in a snow-bound camp.[14][17] His fellow travelers packed him on a horse and traveled along the South Fork of the Eel southward. When they arrived at Santa Rosa, news of their discovery spread.[14]

Gregg's group fared badly. Wood wrote:

They attempted to follow along the mountain near the coast, but were very slow in their progress on account of the snow on the high ridges. Finding the country much broken along the coast, making it continually necessary to cross abrupt points, and deep gulches and canyons, after struggling along for several days, they concluded to abandon that route and strike easterly toward the Sacramento valley. Having very little ammunition, they all came nigh perishing from starvation, and, as Mr. Southard related to me, Dr. Gregg continued to grow weaker, from the time of our separation, until, one day, he fell from his horse and died in a few hours without speaking—died from starvation—he had had no meat for several days, had been living entirely upon acorns and herbs. They dug a hole with sticks and put him under ground, then carried rock and piled upon his grave to keep animals from digging him up. They got through to the Sacramento valley a few days later than we reached Sonoma valley. Thus ended our expedition.[19]

Southard's story of burying Gregg after his death may not be the whole truth. Other reports say he died on February 25 near Clear Lake, California, of poor health and the hardships of his journey,[20] while another casts doubt on the story that his companions buried him, instead suggesting he survived at least briefly at an Indian village.[16] In any case, his papers, instruments, and specimens were lost.[1]

Legacy

Gregg's 1849–1850 expedition has been credited with the rediscovery of Humboldt Bay by land, which resulted in its settlement.[2] The Gregg party's trip triggered an 1850 expedition by Colonel Redick McKee to create treaties with Northern California Indians, which were never ratified.[21]

About eighty plant names were originally assigned to honor Gregg; as of 2002, 47 Mexican and Southwestern plant species bear the specific patronym greggii.[7]

Gregg's portrait, painted by Herndon Davis between 1950 and 1962, is in the collection of the Palace of the Governors, a New Mexico history museum.[22]

Publications

- Josiah Gregg, Commerce of the Prairies, ed. Max I. Moorhead, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1954.

- Josiah Gregg, Diary and Letters of Josiah Gregg, 2 volumes, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1941, 1944.

- Josiah Gregg, "Commerce of the Prairies, or, The Journal of a Santa Fé trader, during eight expeditions across the great western prairies, and a residence of nearly nine years in northern Mexico", 2 vols., Moore, Philadelphia, 1849. Available at https://archive.org/details/commerceofpra01greg

See also

References

- Palmquist, Peter E., Thomas R. Kailbourn, Pioneer Photographers from the Mississippi to the Continental Divide, Stanford University Press, 2005, page 287, ISBN 9780804740579, accessdate 10 March 2013

- Anderson, H. Allen, Gregg, Josiah, Texas State Historical Association Handbook of Texas Online, accessed 17 February 2013.

- Kanellos, Nicolás, Francisco A. Lomelí, Claudio Esteva Fabregat, The Handbook of Hispanic Cultures in the United States, Arte Publico Press, 1993, page 365, accessed 10 March 2013.

- Ruffin, Thomas F. (Summer 1973). "Josiah Gregg and Shreveport during the 1840s". North Louisiana History. 4 (4): 141–148.

- Sargent, Charles Sprague, Garden and Forest, Volume 7, Garden and Forest Publishing Company, 1894, page 7, OCLC 43291639, accessed 10 March 2013, Quote: "He rarely went out, except to the store of his publishers under the Astor House; he never went to the theatre, or, indeed, to any place of amusement. He took no recreation of any kind so far as I could learn. He did not appear to visit anywhere, nor did he appear to have any acquaintances. His heart was wholly in his book; it was his joy by day and his dream by night. His stay and life in the city during its incubation was his great trial. He pined for the prairies and the free open air of the wilderness. New York to him was a prison, and his hotel a cage."

- Gregg, Josiah (1844). Commerce of the Prairies. New York: Henry G. Langley. pp. Two volumes, 320 pp. and 318 pp.

- Blakely, Larry. "Desert Ceanothus, Ceanothus greggii A. Gray var. vestitus (E. Greene) McMinn (Rhamnaceae)". Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Mechem, Kirke, Malin, James Claude, Kansas State Historical Society, Volume 20, Kansas Historical Collections 1952-1953, Topeka, Kansas, accessed 10 March 2013

- Brown, Walter Lee (Winter 1953). "The Mexican War Experiences of Albert Pike and the 'Mounted Devils' of Arkansas". Arkansas Historical Quarterly. XII.

- Horgan, Paul, Of America East and West: Selections from the Writings of Paul Horgan, Macmillan, 1 July 1985. Quote: "He unfortunately became in love—desperately so—and what was more remarkable for a man of his intellect, with a little girl (13 years old) without any special beauty or merit—and still less talent and intelligence."

- Engelmann, George, Plants of Dr. Gregg's Collection, 1846-1847, Missouri Botanical Garden, accessed 10 March 2013

- Horsman, Reginald (1 January 2008). Feast Or Famine: Food and Drink in American Westward Expansion. University of Missouri Press. p. 177. ISBN 9780826266361.

- Moorhead, Max L., ed. (1954). Josiah Gregg, Diary & Letters of Josiah Gregg. Norman, Oklahoma: Norman, University of Oklahoma Press. pp. xxvii–xxix. ISBN 9780806110592.

- Bledsoe, A.J. (1885). Indian Wars of the Northwest, A California Sketch. San Francisco: Bacon and Company. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- Wood, L.K. (1856). "Discovery of Humboldt County". California Traveler (reprint ed.). 2: 1–11.

- McNickles, John R. (March 1932). "A Bit of Trinity History: L. K. Wood's exciting narrative of eight Trinity miners and their westward odyssey to the Pacific and the San Francisco bay in 1849. Summarized by John R. McNickles". Quarterly of the Society of California Pioneers. 9 (1).

- Carr, John (1891). Pioneer Days in California. Eureka, California: Times Publishing Company. pp. 451. OCLC 657036443. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- McDonnell, Lawrence R. (1962). Rivers of California. San Francisco: Pacific Gas and Electric Company. p. 37.

- "History of Humboldt County California Chapter 4". Los Angeles, California: Historic Record Co. 1915. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- "Death of Capt. Gregg". Arkansas Gazette. 19 May 1850.

We regret to learn by the last accounts from California, of the decease of Capt. Josiah Gregg, formerly a resident of Arkansas, and well known as the author of the "Commerce of the Prairies." Capt. Gregg died on 25 Feb., at Clear Lake, California. He joined the company of Trinidad adventurers in November last, and encountered with them the hardships and perils of their fatiguing travel. So incessant and severe were the trials of the journey that his physical powers sunk under them, and an absence of medical attendance, added to general debility, caused his death.

- O'Hara, Susan J. P.; Dave Stockton (16 July 2012). Humboldt Redwoods State Park. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 127 pages. ISBN 9780738595139.

- "Josiah Gregg". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

External links

- Commerce of the Prairies, or, The journal of a Santa Fé trader: during eight expeditions across the great western prairies, and a residence of nearly nine years in northern Mexico, by Josiah Gregg, scan of original editions, H.G. Langley, 1845.

- Josiah Gregg Archived 2009-09-13 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

- Barry Evans, Mad River Lore, North Coast Journal, 12 March 2009

- Plants of Dr. Gregg's collection, scanned field and transmission notes for plants collected, Botanicus.

- Owen C. Coy, The Last Expedition of Josiah Gregg, The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Texas State Historical Association, Volume 20, Number 1, July 1916, pages 41–49.

- Josiah Gregg's 1844 A Map of the Indian Territory, Northern Texas and New Mexico Showing the Great Western Prairies, Maps of the American West, Department of Special Collections and University Archives, McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa, Oklahoma, 13 February 2011.

Further reading

- David Dary, The Santa Fe Trail: its history, legends, and lore, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2000, ISBN 9780375403613.

- Howard T. Dimick, Reconsideration of the Death of Josiah Gregg, New Mexico Historical Review, Volume 22, Number 276, July 1947, pages 315–316, OCLC 8686602.

- Maurice Garland Fulton, editor, Diary and letters of Josiah Gregg, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1941–44. 2 vols.

- Paul Horgan, Josiah Gregg and his vision of the early West, Farrar Straus Giroux, New York. 1979, ISBN 9780374180171.

- Oscar Lewis, The quest for Qual-a-wa-loo, Humboldt Bay: a collection of diaries and historical notes pertaining to the early discoveries of the area now known as Humboldt County, California, Holmes Book Company, 1943, 190 pages, OCLC 1129343

- Frederick W. Rathjen, The Texas Panhandle Frontier, Texas Tech University Press; Revised edition, 15 April 1998, ISBN 978-0896723993.