Juan Martínez de Medrano

Juan Martínez de Medrano y Aibar (Basque: Ganix, Spanish: Juan, French: Jean; 13th century – December 1337-May 1338), called the Elder or the Mayor, lord of Arroniz, Sartaguda and Villatuerta, was Regent of the Kingdom of Navarre from 13 March 1328 until February 27, 1329.[1] Don Juan Martínez de Medrano was a ricohombre and prominent figure of the Navarrese high nobility and main head of his lineage, he participated in the most relevant political events that occurred in the Kingdom of Navarre in the first half of the 14th century. Juan and his son Álvaro Diaz de Medrano are known for their modifications or amendments (amejoramientos) of the Fueros, commissioned in 1330 by King Philip III of Navarre.[2] Philip III, for his services, gave Juan the Castle of Dicastillo and shortly after the town of Arróniz.[3] He was the Lieutenant of the Governor of Navarre, a position he held from 1329 - 1330, and Judge of the Corte of Navarre.

| Juan Martínez de Medrano | |

|---|---|

| Regent of the Kingdom of Navarre with Don Juan Corbaran de Lehet | |

| Reign | 13 March 1328 – 27 February 1329 |

| Predecessor | Charles IV |

| Successor | Joan II |

| Regent | Kingdom of Navarre |

| Born | 13th Century Iguzquiza |

| Died | December 1337 - May 1338 Kingdom of Navarre |

| Spouse | Aldonza Sánchez |

| Issue more... | Juan Martínez de Medrano 'The Younger' Sancho Sanchez de Medrano Álvaro Diaz de Medrano Fernando Sanchez de Medrano Juan Velaz de Medrano Rodrigo Diaz de Medrano |

| House | House of Medrano |

| Father | Juan Martínez de Medrano I |

| Mother | Maria de Aibar |

Rise in Ranks

As a knight, Juan Martinez de Medrano 'El Mayor' held the position of Alcaide in various fortresses of the merindades of Tierra Estella and La Ribera since the end of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th century, such as Viana, Artajo, Asa, and Corella. A trusted person of the Crown, in 1305, Philip the Fair (Philip IV of France, King of Navarra from 1284 to 1305) and the heir Louis X sent him along with the knight Juan de Bochierre with letters destined to calm the kingdom after the death of Queen Juana I. He took center stage in the sociopolitical arena with his appointment as ricohombre (rich man), a dignity that he enjoyed shortly before 1309. Under this condition, along with five ricoshombres and other representatives of the kingdom, he went to Paris for the oath ceremony of Philip V of France on September 30, 1319. Since the beginning of the century, he was known by the nickname "the Elder," undoubtedly to distinguish him from his namesake son, "the Younger," who received a ricohombría in 1323.[4]

Ricohombre of Navarre

Don Juan Martinez de Medrano the Elder and his sons were called ricohombres (rich-men). Ricohombre is a title given to twelve members of the highest nobility in Navarra during the Late Middle Ages, previously known as princes, barons, or lords. In most cases, they were related to the kings. Ricohombre was the highest noble title in the early centuries of Iberian monarchies.[5] In 1329, it still appears that the number of ricoshombres was limited to twelve. It is known that in the oath made by King Philip III and Queen Joan II: Don Juan Martínez de Medrano the Elder and Don Juan Martinez de Medrano the Younger attended.[6]

The title is directly derived from ancient Roman dignities and titles. It only includes those who possess the highest nobility, whether by birth (blood) or by privilege (merit). The origin of this title dates back to the times of the Reconquista. The reason Medrano and his sons were called ricohombre (rich-men) was due to their having many vassals in their service and numerous possessions granted to them by the kings based on their merits in supporting the sovereign in the conquest or repopulation of new lands. The Ricoshombres de Navarra constituted the most privileged sector of the nobility with a high level of social prestige, economic capacity and political attributions in the kingdom of Navarra. From the 12th century, it can be seen that the kings granted the ricohombría to the knights they deemed appropriate and gave them government over one or more towns, assigning them equivalent rents to the number of horses or men that they were to serve the king with in war.

José Yanguas y Miranda, in his Dictionary of Antiquities of the Kingdom of Navarra[7] states that it was: "First dignity of the kingdom among the class of nobility. There is no news of this title being used in Navarre until the 12th century". The General Jurisdiction specifies its functions and dedicates several chapters on private law to them: "It seems according to the general jurisdiction that at first there were only the twelve rich men or twelve wise men of the earth. It is likely that rich and wise were synonymous. The rich men were the king's advisors: without their advice he could not have a court or tribunal (...) nor make peace, war or truce with another king or queen, nor another great feat or royal embargo".[8]

Regent of Navarre

.svg.png.webp)

The House of Medrano gained prominence when the Capetian main line went extinct, as Don Juan Martínez de Medrano became regent of the Kingdom of Navarre in awaiting the arrival of his Queen Joan II and her husband Philippe d'Erveux.[9][10] Medrano's leading role in the political scene came after the death of the last Capetian sovereign, Charles the Fair, on February 1, 1328. The death of Charles, Joan's younger uncle, in February 1328 paved the way for Joan's accession to the throne of Navarre, as there was no longer anyone who could challenge her right to it. The Navarrese, uncomfortable with repressive governors appointed from Paris, were pleased to see the personal union with France come to an end. They held a general assembly at Puente la Reina on 13 March 1328, electing Juan Martínez de Medrano 'The Elder' and Juan Corbarán de Lehet as regents.[11] They assembled again in May, recognizing Queen Joan II as their sovereign. Juan Martínez de Medrano and Juan Corbarán de Lehet were barons of the greatest antiquity. Undoubtedly, the personal prestige of both weighed in an unprecedented election in the history of Navarre.[12] The appointment as regent of Navarre is a rare and distinguished honour. Such appointments were not handed out casually and were reserved for individuals of exceptional capability and loyalty to the crown. The regency of Juan Martinez de Medrano is thus important as the beginning of a new era in the history of Navarre, now once again free from the government of France. Don Juan Martinez de Medrano administered public affairs in the name of Joan II, with the title of regent. A solemn embassy was also sent to Rome, in the name of Joan II, which was extremely well received.[13] Navarre supported this candidacy since they disregarded the Salic Law that counted so much for the French.

The regents dismantled the ruling elite and assumed the supreme jurisdictional faculties corresponding to the Lordship for almost a year until the arrival of the new Monarchs. The regency of Don Juan Martinez de Medrano, which began on 13 March 1328, heralded eleven months of “popular government” in Navarra. During the regency, the exercise of public power clearly manifested its “popular” nature in two ways: through people and through symbols. The change of regime took place via the almost total replacement of those holding public posts; posts which would have went to a group of individuals unrelated to the monarchy and directly committed to the cause of the uprising. Meanwhile, the new Navarrese government led by Medrano and Lehet adapted the royal symbols to the new political situation to reflect the strange, unprecedented situation of a kingdom without a king through such vehicles as language and seals.[14]

The Navarrese had taken certain precautions with the new dynasty when three Frenchmen arrive in Navarre as lieutenants of the kingdom. The regents refused to hand over the powers they had received in the Cortes held in Puente la Reina. They indicate that they would only do so to their "natural lords" once they had presented themselves in Navarre and sworn to abide by the provisions of the Fuero General. They will also be required to agree to other conditions established in the Cortes of Larrasoaña:[15]

- Restrictions on minting new currency

- Prohibition of foreigners holding offices and positions in the kingdom

- Prohibition of selling, encumbering, or exchanging territories of the kingdom

- Their first male child will be crowned king as soon as he turns 20

- In case the queen owner dies before the male child reaches 21, King Felipe should leave the realm so that the successor governs it (which the king accepted not without protesting for forsaking his "right of widowhood," being then compensated with 100,000 pounds of sanchetes)

With the acceptance of these and other conditions that implied serious decisions - "fechos granados" - the ceremony of fidelity oath was held on March 5, 1329, in the Cathedral of Pamplona. The Navarrese regency ended on 27 February 1329 in Larrasoaña, where Juan Martínez de Medrano handed over the seals to Joan and Philip.[16] In the end, both Joan and Philip were crowned, anointed by bishop Arnalt de Barbazan and raised on the shield in Pamplona Cathedral on 5 March 1329. On that day, Don Juan Martínez de Medrano participated in the royal oath and raised his voice on behalf of the ricoshombres and estates, a genuine representation of the kingdom. The most prestigious surnames reflected in ‘The Book of Armory of the kingdom of Navarre’ corresponded to very active families in Navarrese politics from the beginning of the 13th century to the first half of the 14th century. Upon arrival of Charles II to the Navarrese throne, few of those famous surnames were part of the social dome: only Monteagudo, Medrano and Lehet remained as rosters of the old noble preponderance.

Medrano's Brotherhood between Navarrese and Gipuzkoans

In 1328, his son, the merino ("mayorino" or sheriff, the representative of the king) in the merindad of Estella, Juan Velaz de Medrano, knight, with ten horsemen and sixty foot soldiers, marched to meet with Don Beltran Ibañez de Guevara, lord of Oñate and with those from Álava and Salva-Tierra of the Kingdom of Castile in order to discuss peace and harmony between the borders of the Kingdoms of Navarre and Castile. In 1329 the first border brotherhood was established between Navarrese and Gipuzkoans. Don Juan Martínez de Medrano the Elder, Lieutenant of the Governor of Navarre, at the request of the Council of Segura, rode with six horsemen and five hundred and sixty foot soldiers to the said Gipuzkoan town after the cattle and pigs of Santa Maria de Iranzo (Iranzu) that Garci Ivaynnes de Arbizu stole, and recovered them, delivering them to the monks. And on this, the men of Gipuzkoa requested that he send the Merino of Pamplona to make a brotherhood with them, for themselves and those of his jurisdiction, seeing the benefits that could come to the people of the King, who are in the said jurisdiction and in the jurisdiction of the merindad of Estella, Don Juan Martínez de Medrano the Elder granted and made a brotherhood with the said Gipuzkoans for five years.

The treasurer of the kingdom informs that this brotherhood had been requested by the residents of Segura. The Merino of Pamplona, by order of Lieutenant Juan Martínez de Medrano the Elder, and at the request of the good men of San Sebastian, Hondarribia, and Tolosa, went to this town to make a brotherhood with the said Gipuzkoans, as well as with those of Segura; he stayed for four days until the said brotherhood was made. The officials narrate the contract made between the Merino of Pamplona and those from Segura for five years, and how later it was extended to the councils of San Sebastián, Fuenterravía and Tolosa at their request. The King, wishing to provide a suitable remedy for the killings and cattle thefts committed by the men of Gipuzkoa in the land of Burunda and Aranaz, ordered that a hundred men be prepared to defend the border.

During this period, the unruly elements of Gipuzkoa were grouped around the restless and criminal lineages of Lazkano and Oñaz. Two curious Latin accounts, both from the Merino of Pamplona, clearly indicate this. The first one is titled "Account of Johan Garssia de Reta, Merino of Pamplona, for the expenses he incurred when he went to Gipuzkoa with armed men to aid justice and the Brotherhoods of said land, to administer justice and punish the wrongdoers who had caused many and great damages in the Kingdom of Navarra, by order and letter of the Governor communicated on June 16, 1330." The Merino was in Sangüesa on Saturday, June 16 when he received the order to go to Gipuzkoa.

The circle of the brotherhood was very broad, comprising:

the valley of Arakil, the towns of Atahondo (Atondo), Murco (which no longer exists), Anoz, San Andrés de Lehet, Artiga (which no longer exists), Ochobi, Heritze (Erice), Sandaynna (which does not exist?), Sarassa, Sarde (which does not exist), Sarluz (id.), Andaz (id.; the five deserted places belonged to the cendea of Iza); the valleys of Bullina (Gulina), Utzama (Ulzama), Odieta, Atez, the town of llarregui (this hamlet is now part of the Ulzama valley), the Lana valley, the town of Eztuniga (Zúñiga), the valleys of Amescoa, Arana, Larraun, Araiz, Bassaburua mayor, Imoz, Deyerri with the monastery of Iranzu, Lerín, Bassaburua menor, the land of Baztan, the five towns near the Lerín valley (Sumbilla, Yanzi, Lesaka, Echalar and Bera), the valley of Anué, the town of Lanz, the valleys of Ezcabart (Ezcabarte), Olabe (this valley is officially called today by its genuine Basque name Olaibar; Olabe is one of its towns), Oyllo (Ollo), San Estéban (this is the valley of Santésban de la Solana, in the Merindad of Estella), Burunda, Araynnaz (Aranáz), the towns of Bernedo and its hamlets, Aguilar, Hussanavilla (Genevilla), Cabredo with its hamlets, Torralba, the valleys of Ega, and La Berrueza.

The Brotherhood had to pay the king a certain aid or compensation for the expenses in destroying the fortress of Larrea and correcting the wrongdoers of Gipuzkoa who caused deaths and robberies in said Brotherhood. Several of these localities refused to pay, arguing that they did not belong to the brotherhood and with exemptions from the Governor. In addition to the towns and valleys mentioned, the herds of the Hospital de Sta María de Roncesvalles in the Andía mountains, those of Belate, Elicano, Eli- berri, Moz Helia, Irach (the Monastery of Irache), Pedro Sanchiz de Bertiz, Burunda, and the blacksmiths of Leiza, Cinco Villas and the Lerín valley, contributed to the expenses of the destruction of Larrea. In each region or district there was a collector. The total amount of the collection was three hundred and eighty-eight pounds, thirteen sueldos, and one dinero.

About this brotherhood there is not much more news. Although it was conceived for five years, it soon had to be dissolved. In fact, in 1334 it is mentioned that the brotherhood of Guipúzcoa, together with those of Lazcano, had surrounded the castle of Ausa. This brotherhood might have only continued in force during the year 1330; that year, the merino from Pamplona, Juan García de Reta, collected the income from a tax created to support the brotherhood. Medrano's border brotherhood of 1329 is therefore really reduced on the Navarrese side to a treaty with the towns of Guipúzcoa, in which some promise the others to act against the criminals who attack the neighboring territory and who they take refuge in their own.

The border skirmishes carried out by Oñacino lineages from Gipuzkoa and by the royal officials of the kingdom of Navarre in the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries have been extensively covered by Navarre historiography. It seems, in particular, that the first half of the 14th century was one of the periods that saw the greatest border instability. In fact, it is during these years that the famous confrontation in the Beotíbar gorge took place, where the Navarrese suffered a significant defeat. On the other hand, the disputes, brawls and border persecutions are not characteristic only of this time, but rather they follow one another with virulence throughout the entire century.[17]

Amejoramiento of the Fueros of Navarre 1330

The prestige achieved by Juan Martínez de Medrano the Elder, a judicious man versed in negotiation, did not cease with the restoration of the Monarchy. Juan Martínez de Medrano attended the Cortes meetings as a Judge in which the succession issue was settled, and his modifications or amendments (amejoramientos) of the Fueros was approved. The Navarrese had "returned to their fueros." The "Amejoramiento" of the Fuero General, elaborated during the time of Sancho el Sabio, with the consent of the Cortes in 1330, is attributed to Don Juan Martinez de Medrano 'The Elder' and his son Álvaro Diaz de Medrano, commissioned by Felipe de Évreux.

In addition to these public appearances, conditioned by his rank, his harmony with the house of Évreux was evident in the appointment of lieutenant of the governor, a position he held at least in 1329 and 1330. As a sign of this high degree of trust, in 1333 and 1334, he was one of the witnesses in the agreements for the marriage of Princess Joan to Pedro, the eldest son of the kings of Aragon. Pedro, who ascended the throne in January 1336, expressed a preference for the second daughter, which forced Joan to renounce her succession rights in favour of Maria of Navarre.[18]

The Monastery of Fitero

Juan Martinez de Medrano 'The Elder' must have enjoyed great power and reputation as a prudent man, since the kings of Navarre and Castile chose him as the arbitrator of their differences so that he would settle them according to his conscience at the beginning of the year 1331. In 1336, Juan Martínez de Medrano was again chosen to be the arbitrator, this time, over the border dispute concerning the ownership of the Monastery of Fitero that had developed into a war with Castille in 1335. Having successfully arbitrated between the two kings, Navarra signed a new peace treaty with Castille on 28 February 1336. The matter was not resolved until 1373 when it was concluded that the Monastery of Fitero had always belonged to Navarre.[19]

Assets

Regarding his possessions, besides receiving temporary rents, in 1312 the Irache Abbey gave him a palace, church, and property in Torres del Río. In 1332 he was called the lord of Sartaguda, and shortly after, the lord of Arróniz and Villatuerta. In 1342, his heirs sold the town of Arróniz to the King for 48,500 sueldos, except for the chaplaincy he himself had founded and a house that his son Álvaro Díaz retained. His other son, Sancho Sánchez de Medrano, proceeded in the same way with the sale of the lordship of Villatuerta. It was actually a forced sale because these properties were linked to the debt letters that the crown had taken from the Jewish banker Ezmel de Ablitas.[20]

Judas (brother of Abraham Ezquerra) was also in debt to the Medrano family in the year 1341[21] when his son Açach signed a letter as a witness for a debt of one hundred and twenty pounds of small torneses. The indebted party was the affluent Jewish merchant Judas Abenavez, son of Don Ezmel de Ablitas, known as "El Viejo". This debt was owed to Sancho Sánchez de Medrano, the lord of Sartaguda,[22] along with his wife María Pérez and Juan Pérez de Arbeiza, the chief magistrate of the Court of Navarra. Sancho Sánchez de Medrano was a wealthy and influential figure of the time, a member of the well-known Medrano family. He was the son of Juan Martínez de Medrano the Elder, who held considerable influence in the Navarrese government.[23][24]

Marriage, Death and Children

Married to Aldonza Sánchez, Juan Martínez de Medrano 'The Elder' died between December 1337 - May 1338 and left a long list of descendants who reinforced his lineage:

- Juan Martínez de Medrano 'The Younger'

- Sancho Sanchez de Medrano

- Álvaro Diaz de Medrano

- Fernando Sanchez de Medrano

- Juan Vélaz de Medrano

- Rodrigo Diaz de Medrano

One of his daughters was married in 1318 to the nobleman Ramiro Pérez de Arróniz. The regent's namesake son, the nobleman Juan Martínez de Medrano 'The Younger' died around 1333 and left several children, Juana, Bona, Toda, and another Juan Martínez de Medrano, a knight of Tierra Estella since 1343 and a nobleman in 1350 at the coronation of Carlos II. Dona Toda Martinez de Medrano, Lady of Santa Olalla y Sarria, daughter of Juan Martinez de Medrano 'The Younger', married the famous knight Don Fernando de Ayanz, Lord of Mendinueta.[25] Toda Martinez de Medrano and Fernando's son Don Ferrant Martinez de Ayanz y Medrano, II Lord of Guenduláin, married Dona Leonor de Navarra, daughter of Prince Leonel, I Vizcount of Muruzábal,[26] and granddaughter of Charles II of Navarre.[27] King Charles III of Navarre, her carnal uncle, offered Dona Leanor 4,000 pounds of dowry, and in guarantee of it, gave Don Ferrant Martinez de Ayanz y Medrano, in 1417, the pechas of Lizarraga.[28] The marriage between Don Ferrant Martinez de Ayanz y Medrano and Dona Leonor de Navarra created the royal Ayanz de Navarra branch.[29] Their son Don Juan Ayanz de Navarra was the first of the Ayanz de Navarra, Lord of Guendulain, Agos and Orcoyen, from the palaces of Sarria and from the pechas of Piedramillera, Galdeano, Aucin and Mendiribarren.

In 1328, the regent's son Don Juan Vélaz de Medrano appeared as the Alcaide of the Tower of Viana. He received an emolument of 35 pounds.[30] Don Juan Velaz de Medrano, third of the name, Alcaide of Viana[31] and Dicastillo died in 1342. He married Dona Bona de Almoravid and was the father of Don Alvar Diaz de Medrano y Almoravid, ricohombre (rich man) of Navarre, Alcaide of the famous Monjardin Castle (San Esteban de Deyo) in 1380; and the following two years he was listed among the King's Mesnaderos.[32][33] Don Alvar Diaz de Medrano y Almoravid commanded a retinue or company of armed people in the service of the king. Mesnadero, (In Basque: Mesnadaria) is one who served in the mesnadas. Mesnadero's were the cadet sons of a Ricohombre. The kings granted Alvar Diaz de Medrano a certain income with the obligation to serve him with weapons and horses for a limited time when necessary. It comes from Mesnada, which would mean house, because it was a troop of the Royal House. In Navarra, the mesnaderos were later called remiszados because they were exempt from paying barracks. In 1351, the king granted the Remiszado (Mesnadero) Don Martin Ferrandez de Medrano 40 pounds per year of allowance, on the condition that he was always rigged with horse and arms with a companion, as a pertescia mesnadero. The 40 pounds were a double allowance or two allowances, for which reason he required two warriors, since in the same year the king made Arnal de Ceylla and Martin de Agramont his messengers with 20 pounds each, always being rigged with weapons and horses as innkeepers.[34]

The death of Juan Martínez de Medrano 'The Younger' left his brother Don Sancho Sánchez de Medrano as the main heir and head of the lineage. Sancho Sánchez de Medrano married María Pérez de Arbeiza, daughter of the prestigious mayor of Cort Juan Pérez de Arbeiza, he received the lordship of Sartaguda at the death of his father and was named a nobleman, although he had disappeared by 1350.

Fernando Sanchez de Medrano replaced Sancho Sanchez de Medrano as the main head of the Medrano lineage and participated as a nobleman at the coronation of Charles II of Navarre.[35] The coronation of King Charles II of Navarre was celebrated solemnly in Pamplona on Sunday, June 27, 1350, with the three Estates of the Kingdom gathered together in the Cathedral Church. The record of that ceremony introduces the names of the high ecclesiastical dignitaries, the magnates who had the honour of the places and fortresses, and the representatives of the good towns during the beginnings of that reign, undoubtedly the most suggestive in the history of Navarra. The following persons personally appeared, the Barons: Lord Juan Martinez de Medrano and Fernando Sanchez de Medrano.[36]

Notable Descendants of the Regent

Don Juan Martinez de Medrano's future descendants would prove to be key players against the Spanish conquest of Iberian Navarre. The Alcaide Don Juan Velaz de Medrano y Echauz defended his castles of Monjardin and Santacara in 1512 against Castile;[37] and his brother the Alcaide and Mayor of Amauir-Maya Don Jaime Velaz de Medrano y Echauz (b. 1475) with his son Don Luis Velaz de Medrano, defended his Castle of Maya at the battle of Amauir-Maya (1522), the last royal Navarrese stronghold in an attempt to resist the Spanish (Castilian-Aragonese) push in the Kingdom of Navarre sent by Isabella's grandson Emperor Charles V.[38]

After the conquest of Navarre, the Medrano family would go on to hold the regency of Navarre two more times. Garcia de Medrano y Alvarez de los Rios was the regent of the Audience of Seville, and he was elected Regent of Navarre on January 17, 1645 for King Charles II.[39] Don Pedro Antonio de Medrano y Albelda would also become regent of the Royal Council of Navarre from 1702 to 1705 for King Philip V.[40] Don Juan Martinez de Medrano was also a direct ancestor of Luisa de Medrano, professor at the Universtiy of Salamanca.

Ancestry

Don Juan Martinez de Medrano 'The Elder' is the son of Don Juan Martinez de Medrano and Maria de Aibar. The house of Aibar is one of the oldest lineages of Navarre, to the point that some scholars say that its origin dates back to the times of the Visigothic King Reccared I. Others mention Iñigo de Aibar, including him among the twelve noble men who were elected in the year 865 to govern Navarre. The lineage had its ancestral home in the town of Aibar (which it likely gave its name to).[41]

Don Juan Martinez de Medrano I

His father Don Juan Martinez de Medrano I was the son of Inigo Velaz de Medrano. Don Juan Martinez de Medrano I was the Lord of Sartaguda and Ricohombre of Navarre, as confirmed by several Royal instruments of the year 1291.[42] In 1260 AD, the regent's father was given the tower of Viana by the king of Navarre. His father was designated as the person responsible for defending the town and villages in that area on the border of Navarra with Castilla. As a result, his prestige rose, since in 1300 the council of Viana recognized the representation that his father Juan Martínez de Medrano made before the kings of Navarra defending their claims to the Kingdom. However, the presence of the Medrano family in the town also generated tensions and conflicts. In 1310, a peace agreement was finally reached between Don Juan González de Medrano, the moneylender of Viana, and the council of Viana, whose confrontation was considerable.[43] There had been deaths on both sides, who gave up their hostilities, disputes, and violence. The Medrano family maintained a relative influence in the town in the second half of the 14th century and until the mid-15th century. In the mid-15th century, the Vélaz de Medrano family continued to lead a military garrison in Viana.

Don Inigo Velaz de Medrano

The regent's paternal grandfather was Don Inigo Velaz de Medrano, Lord of Sartaguda. Don Inigo Velaz de Medrano was in the Eighth Crusade with the kings Louis IX of France and Theobald II of Navarre.[44] The Basque Nobility marched to the Crusade with their King Theobald II of Navarre, and under the supreme direction of the Holy King Louis IX of France. Don Inigo Velaz de Medrano was called and chosen by the King. Don Inigo Vélaz de Medrano, and many other noblemen of no less quality answered the call.[45] The expedition departed from the ports of Marseille and Aguasmuertas at the beginning of July 1270 on ships. The seal of this knight Don Inigo Velaz de Medrano is preserved in several documents, including the one containing a donation from the king to the monastery of Leyre (1268).[46] Don Inigo Velaz de Medrano is the son of Don Pedro Gonzalez de Medrano.

Don Pedro Gonzalez de Medrano

The regent's paternal great-grandfather was Don Pedro Gonzalez de Medrano, who attended the victorious day of Las Navas de Tolosa (16 July 1212), forming part of the brilliant retinue that accompanied Sancho VII of Navarre, and constituted the most significant nobility of the Kingdom.[47] Don Pedro Gonzalez de Medrano was noted at the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa on July 16 1212 and took up his own coat of arms: Gules Shield and a silver cross, figured as that of Calatrava.[48]

Progenitor of the Medrano Lineage

They are all descendants of a common ancestor who was called Medrano. The origin of the Medrano surname is not a mere coincidence.[49] In fact, It is common knowledge amongst historians and scholars that the noble Medrano family lineally descend from their progenitor, a Moorish Prince from Umayyad Andalusia.[50] This Prince settled in Iguzquiza under the protection of King Sancho II of Pamplona.[51]

He arrived in Iguzquiza leading a powerful army, entering Navarra around the year 979. He is supposed to have secretly been devoted to the Blessed Virgin, and as such persecuted by the devil, who, taking human form, was in the position of mayordomo in his service, to assassinate him at an opportune moment; this great lord, being in Igúzquiza accompanied by his diabolical mayordomo, was reciting the Ave Maria, when suddenly a goshawk came, carrying a ribbon written with the angelic salutation in its beak, and alighting on the hand of this prince, the Apostle St. Andres suddenly appeared in the enclosure, exhorting and baptizing him. The mayordomo fled with great noise and terrifying earthquakes.[52]

This Prince was a lord of vassals, a person of great valor in arms, who was fond of the Christian religion, and in particular very devoted to the Virgin Mary, whose Rosary he prayed every day, even before being baptized. He left his lands and lordship in the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba. The king of Pamplona gave him the name Andres (after the apostle) along with Velaz or Belaz (Basque for goshawk, after the one that alighted on his hand). Since Andrés Velaz was very powerful among the Moors, having great riches, which he lost at that time; the Caliph of Cordoba, amazed at his change, and that he had thus left his lands and lordship, asked about Don Andrés Velaz many times afterwards saying, "Medra o no?" (Does he prosper or no?) to which the Caliph's courtiers replied "no". Don Andrés Velaz, having knowledge of this, took the Caliph's question and his people's answer as his surname, and called himself Medrano.[53] The palace of Andres Velaz de Medrano and his lordship of Iguzquiza became the family seat of the Medrano family for over 800 years.

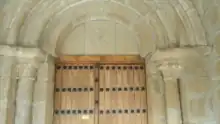

The Palace of Velaz de Medrano was built by Don Andres Velaz de Medrano and his descendants in the beginning of the 11th century. First it consisted of a large palace defensive tower (with machicolations, battlements, saeteras) surrounded by a wall with four fortified towers in the corners, guarded by a moat at the entrance. Subsequently to the tower was added a building with outbuildings to make the palace more habitable, all built in ashlar stone. The palace was rebuilt in the middle of the 15th century by Don Ferran Velaz de Medrano, Lord of Iguzquiza and Learza. It is accessed through a semicircular arch marked with voussoirs and the ancient coat of arms of the Medrano family on the keystone. This door opens onto the parade ground, one of whose corners is occupied by the ashlar palace and cushioned ashlar at the base. In the southeast angle rises the fortified tower, also rebuilt, on a base of ashlar and the rest of brick. It has arrow slits and is covered in the upper area by machicolations to harass the enemy. The rear part is the oldest and there is a square-shaped tower built in ashlar and increased in brick, with the wall opened by loopholes and a lowered arch. The Palace of Velaz de Medrano was famous for the splendor of the festivities celebrated there by its Lord Ferran Velaz de Medrano, his sons, and his grandchildren, which were often attended by the Navarrese monarchs themselves.[54] The Palace of Velaz de Medrano remains today overlooking the municipality of Iguzquiza.[55]

The parish church of Igúzquiza,[56] which bears the name of the apostle San Andres and boasts valuable Romanesque lineage and the chi-rho or labarum of Constantine; housed in its presbytery are several military trophies, flags, weapons, gauntlets, helmets, and spurs, probably donated by the Medrano family upon returning from an unspecified warlike enterprise. These trophies can only be attributed to Medrano, as there is no memory of another character in the locality of Iguzquiza who has held such a high or martial position as Medrano. The surname was associated with: Martinez, Sanchez, Sanchiz, Fernandez, Diaz, Iñiguez, Gonzalez, Lopez, and especially with Velaz or Belaz. This family is not to be confused with the lineage of Vela Landron or the house of Vela.

Coat of Arms of Medrano

.jpg.webp)

Coat of Arms of Medrano in Navarre: The earliest coat of arms of Medrano was taken up by the Moorish Prince Don Andres Velaz, progenitor of the Medrano family. Don Andres Velaz de Medrano is noted for having a coat of arms; it displayed a goshawk in his hand and the Ave Maria written on paper in the beak, with the crosses of San Andres adorning the shield.[57] This shield is an early prototype, as the heraldry system was developed in northern Europe in the mid-12th century. This coat of arms has remained within the Medrano family, with few variations:

- In Gules, a hollow and gilded cross, in gold, accompanied in the right corner of the chief, by a hand, with a silver goshawk, silver border with the legend: "Ave Maria Gratia Plena, Dominus Tecum" in saber letters.[58]

- Gules, silver trefoil cross, silver border with the motto or legend: "AVE MARIA GRATIA PLENA DOMINUS TECUM"[59] There is a municipality named Medrano in La Rioja with this coat of arms featuring a gold castle and two gold lions on a field of gules. Since the inclusion of the lion element, which is the noblest of the figures together with the goshawk or eagle, means that, the Medrano family origin is very old; generally, the holders of such a symbol were related to royalty.[60]

- The Solar Primitive: Gules, a flordelized cross, hollow. Silver border, with the inscription, in black letters: "Ave María, Gratia Plena". Variations: the silver cross and charged with a red Greek cross; a blue border, with oro letters of their family motto.[61]

References

- Basque Encyclopedia, Medrano, Juan Martinez, de https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/medrano-juan-martinez-de/ar-94014/

- F. Segura Urra, ‘Fazer justicia’. Fuero, poder público y delito en Navarra (siglos XIII-XIV), Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2005, págs. 39, 173, 313, 321 y 388 https://www.heraldrysinstitute.com/lang/en/cognomi/Velaz+De+Medrano/idc/630501/

- Yangunas, Diccionario, etc., art. Medrano [Adiciones al]

- https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/57535/juan-martinez-de-medrano

- M, J. d'W (1863). Diccionario militar: contiene las voces técnicas, términos, locuciones y modismos antiguos y modernos de los ejércitos de mar y tierra (in Spanish). L. Palacios.

- "RICOSHOMBRES - Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia". aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- Iribarren Rodríguez, José María (1963). "Yanguas y Miranda: (su vida y su obra)". Príncipe de Viana. 24 (92): 215–229. ISSN 0032-8472.

- "RICOSHOMBRES - Related - Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia". aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- The Official Gascon Rolls http://www.gasconrolls.org/indexes/entity-011516.html

- Moret: Anales de Nabarra, (ano. 1328)

- Orella Unzué 1985, p. 465. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/15737.pdf

- Royal Academy of History https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/57535/juan-martinez-de-medrano

- The Modern Part of a Universal History, From the Earliest Account of Time: The History of Navarre, (J) L'histoire du Royaume de Navarre, Ferreras, Mayerne Turquet, Page 464 https://books.google.ca/books?id=CE0BAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA464&lpg=PA464&dq=the+history+of+arroniz,+navarre&source=bl&ots=TeFTG8MeUR&sig=ACfU3U0nP8bvgYMza1SuAobl3Ek9fBax0Q&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiO5v_frb33AhVFCM0KHR_yCd8Q6AF6BAgoEAM#v=onepage&q=the%20history%20of%20arroniz%2C%20navarre&f=false

- J. Zabalo Zabalegui, La administración del reino de Navarra en el siglo XIV, Pamplona, Universidad de Navarra, 1973, págs. 37, 53, 55-56, 210 y 323 https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/57535/juan-martinez-de-medrano

- Medieval History of the Kingdom of Navarre by Carlos Sanchez-Marco http://www.lebrelblanco.com/14.htm?&cap=3

- Segura Urra, Félix (2018). "Martínez de Medrano, Juan". Diccionario biográfico español. Real Academia de la Historia https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/57535/juan-martinez-de-medrano

- Mugueta Moreno, Iñigo (2000). "Acciones bélicas en Navarra: La frontera de los malhechores (1321-1335)". Príncipe de Viana. 61 (219): 49–78. ISSN 0032-8472.

- Surget, Marie-Laure (2008). Mariage et pouvoir : réflexion sur le rôle de l'alliance dans les relations entre les Evreux-Navarre et les Valois au XIV siècle (1325–1376). Laboratoire d'éthnographie régionale.

- Archivo de Comptos, canjon 7, nums. 62 y 28.

- “Juan Martínez de Medrano ‘el Mayor’”, en Gran Enciclopedia Navarra, vol. VII, Pamplona, Caja de Ahorros de Navarra, 1990, páge 310

- Castro, 1948, p. 94

- Yanguas and Miranda, 1843, p. 200

- Ávila, 1987, pp. 9-57

- Cultura Navarre Príncipe de Viana (PV), 273, enero-abril, 2019, 133-157 Page 143 https://www.culturanavarra.es/uploads/files/PV273_07_avila.pdf

- "Ayanz family heraldry genealogy Coat of arms Ayanz". Heraldrys Institute of Rome. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- https://www.geni.com/people/I-Vizconde-de-Muruz%C3%A1bal-Leonel-de-Navarra/6000000010771380854

- Aleson: Anales de Navarra, years 1418

- Archivo de Comptos, cajon 120, num 35; cajon 105, num. 16

- Royal Heraldry Institute of Rome 'Ayanz' https://www.heraldrysinstitute.com/lang/en/cognomi/Ayanz/idc/651059/

- Fernández, Ernesto García. "Ernesto García F. Viana". GARCÍA FERNÁNDEZ, Ernesto “Cristianos y judíos en los siglos XIV y XV en Viana. Una villa navarra en la frontera con Castilla”, en Viana. Una ciudad en el tiempo. Analecta Editorial, Pamplona, 2020., pp. 117-158.

- Archivo de Comptos, cajon 8, num 9. El Hermano mayor fue Sancho

- Idem id., cajon 12, num 59

- MESNADERO https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/mesnadero/ar-95422/

- Gran Encyclopedia of Navarre http://www.enciclopedianavarra.com/?page_id=11456

- F. Segura Urra, ‘Fazer justicia’. Fuero, poder público y delito en Navarra (siglos XIII-XIV), Pamplona, Gobierno de Navarra, 2005, págs. 39, 173, 313, 321 y 388 https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/57535/juan-martinez-de-medrano

- The History and Geneology of Spain Pg. 83 https://ia800207.us.archive.org/16/items/revistadehistori01madruoft/revistadehistori01madruoft.pdf

- https://nabarralde.eus/es/el-castillo-de-santacara/

- "LAS CARTAS DE AMAIUR | Correspondencia personal del alcaide y capitán navarro Jaime Vélaz de Medrano. – Editorial Mintzoa – Historia de Navarra" (in European Spanish). Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- 'Garcia de Medrano y Alvarez de los Rios, Regent of Navarre' https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/31027/garcia-de-medrano-y-alvarez-de-los-rios

- 'Don Pedro Antonio Medrano Albelda, Regent of Navarre and Seville' https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/38045/pedro-antonio-medrano-albelda

- Heraldry Institute of Rome 'Aibar' https://www.heraldrysinstitute.com/lang/en/cognomi/Aibar/idc/651023/

- Archivo de Comptos, canjon 2, num. 112; canjon 6, num. 18

- Viana Municipal Archive. Folder 14, Letter X, number 1

- Cervantes, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de. "Españoles en las cruzadas". Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- Nobilario y Armeria General de Nabarra (Picina,-Moret: Anales de Navarra, Escolios y adiciones al reinado de Teobaldo II.) https://www.euskalmemoriadigitala.eus/applet/libros/JPG/022344/022344.pdf

- Archivo de los Bajos Pirineos. – Leire

- V. El sequito Del Rey Fuerte – Pamplona 1922.

- Nobiliary of the kingdoms and lordships of Spain. Francisco Piferrer. 1858 Volume I. 400) Tomo II. 973 https://books.google.com/books?id=m1UBAAAAQAAJ&dq=medrano+viana&pg=PA194

- "Medrano". Armorial.org (in French). 25 October 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- Pineda, Pedro (1740). New dictionary, spanish and english and english and spanish : containing the etimology, the proper and metaphorical signification of words, terms of arts and sciences ... por F. Gyles.

- "MEDRANO - Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia". aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- Las casas señoriales de Olloqui y Belaz de Medrano, 'EL PALACIO DE BELAZ DE MEDRAN0' Page 38 - 43

- Mosquera de Barnuevo, Francisco (1612). La Numantina de el licen.do don Francisco Mosquera de Barnueuo natural de la dicha ciudad. Dirigida a la nobilissima ciudad de Soria . National Central Library of Rome. Impresso en Seuilla : Imprenta de Luys Estupiñan.

- Dictionary of antiquities of the kingdom of Navarra, with additions, Volume 1 https://books.google.ca/books?id=pnEIAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA202&lpg=PA202&dq=velaz+de+medrano+iguzquiza&source=bl&ots=tagvA2zA5e&sig=ACfU3U397o7s58tGXBXEv1wtar5MOE6w1w&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi_yaKO9sP5AhVfj4kEHY6XCEEQ6AF6BAgEEAE#v=onepage&q=medrano&f=false

- The Palace of Velaz de Medrano https://goo.gl/maps/KE5kaX9CVZahg1F68

- The Parish Church of Iguzquiza

- Las casas señoriales de Olloqui y Belaz de Medrano, 'EL PALACIO DE BELAZ DE MEDRAN0' Page 38 - 43 https://listarojapatrimonio.org/lista-roja-patrimonio/wp-content/uploads/Las-casas-se%C3%B1oriales-de-Olloqui-y-Belaz-de-Medrano.pdf

- AA.VV; Familiar, Instituto de Historia y Heráldica (22 October 2014). Apellido Velaz de Medrano: Origen, Historia y heráldica de los Apellidos Españoles e Hispanoamericanos (in Spanish). Instituto de Historia y Heráldica Familiar.

- "Viana Digital Archive - Heráldica de Viana: Blasones del Reyno de Navarra". Viana Digital Archive - Heráldica de Viana. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- "López de Medrano family heraldry genealogy Coat of arms López de Medrano". Heraldrys Institute of Rome. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- "MEDRANO - Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia". aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus. Retrieved 11 October 2023.