Juanita Nielsen's House

Juanita Nielsen's House is the heritage-listed former house of murdered activist and journalist Juanita Nielsen at 202 Victoria Street in the inner city Sydney suburb of Potts Point in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. It was built from 1855 and designed in the Federation filigree. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 27 June 2014.[1]

| Juanita Nielsen's House | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | 202 Victoria Street, Potts Point, City of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33.8737°S 151.2227°E |

| Built | 1855– |

| Architectural style(s) | Federation filigree |

| Official name | Juanita Nielsen's House |

| Type | state heritage (built) |

| Designated | 27 June 2014 |

| Reference no. | 1929 |

| Type | Terrace |

| Category | Residential buildings (private) |

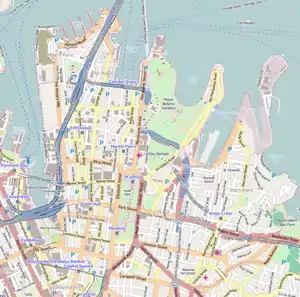

Location of Juanita Nielsen's House in Sydney | |

History

The "Eora people" was the name given to the coastal Aborigines around Sydney. Central Sydney is therefore often referred to as "Eora Country". Within the City of Sydney local government area, the traditional owners are the Cadigal and Wangal bands of the Eora. With the invasion of the Sydney region, the Cadigal and Wangal people were decimated but there are descendants still living in Sydney today.[1]

202 Victoria Street is one of a group of three terraces erected in the 1850s on the former Telford Lodge estate in Darlinghurst.[1]

In 1828 Governor Darling assigned to his senior government officials 15 exclusive villa estates on land he had subdivided from the governor's former reserve which lay immediately east of the town boundary of Sydney. This area was initially named Woolloomooloo Heights and later renamed Darlinghurst.[1]

A condition of the land grants was the building of a villa. In 1829, the deceased Colonial Treasurer's grant was reassigned to Edward Hallen (1803–80), a draughtsman to the Surveyor General. Hallen built his villa, Telford Lodge, in 1832. (The building survives in a much modified form, on Brougham Street, Potts Point).[1]

Darling's plans for the establishment of exclusive villa estates on the eastern boundary of Sydney were short-lived. Subdivision of these estates began in the early 1840s, driven by the onset of the colony's first economic downturn coupled with an increasing demand for land for housing from Sydney's rapidly growing population.[1]

Hallen was among the first of the villa landowners to subdivide his holding and sell his villa. Subdivision of the Telford Lodge estate between 1841 and 1843 created the northern end of Victoria Street which was included within the boundaries of the newly created City of Sydney in 1842. Victoria Street was aligned in 1848 and by 1854 allotments had been set out on both sides of the street. Larger lots were created at the northern end of Victoria Street, for residences with harbour views. The southern end of Victoria Street (towards William Street) was characterised by small narrow lots for workers cottages and terraces. By 1854 the allotments immediately south of No. 202 had been built on.[1]

Victoria Street was renumbered in the 1870s. From the mid 1850s until 1870 the three terraces at 198-202 Victoria Street were numbered as 204-208. The City of Sydney Rate and Valuation records indicate that Nos 204-208 Victoria Street were constructed between 1855 and 1858. They were in common ownership and are described as two storey "brick and shingled" with two rooms. The 1865 Trigonometrical Survey shows the three terraces built flush to the street with no verandah and each with an outhouse (toilet) in the rear yard.[1]

Nos. 198-202 Victoria Street are typical of the development on the small lot subdivisions that characterised the southern end of Victoria Street in the mid nineteenth century. The terraces were mainly occupied by working men and their families in a succession of tenancies until the mid twentieth century. Few tenants stayed for long periods.[1]

Until the 1890s, the majority of larger residential buildings along Victoria Street were occupied as private residences. But by the 1890s, large numbers of "residential" and boarding houses were listed along Victoria Street and surrounding streets. The demographic change was in part due to the steady move of those who could afford to into the newly developing outer suburbs. This move was promoted by improvements in public transport, which made it possible (and affordable) to travel from the suburbs into the city on a daily basis. It was also promoted by the rhetoric of social reformers. The inner city area developed an unfavourable reputation that was only reinforced by the bohemian lifestyles of some of the "fringe-dwellers", artists, writers etc. who were attracted to the area during the interwar period and the presence of American servicemen during World War II.[1]

Among the late nineteenth and early twentieth century owners of the terraces was the winemaker, Isaac Himmelhoch, who owned the terraces between 1893 and 1913. Himmelhoch was a businessman who owned a large amount of inner city property. Thomas Playfair, who owned the terraces between 1916 and 1925, was a member of a Sydney butchery and meat provedore family, who had served with distinction in World War I. In 1927 he became a member of the New South Wales Legislative Council and was influential in the establishment of the United Australia Party. In 1926 Playfair sold the five terraces to Anna Hindmarsh who retained ownership until 1958.[1]

The titles for the jointly held properties at 198–202 Victoria Street and 11–13 Earl Street were separated in 1958.[1]

Rate and Valuation Records indicate that Nos. 198 and 202 Victoria Street were, as were many of their neighbours, occupied as mixed commercial/ residential buildings at various times from the 1950s through to the 1980s. In 1958 Gregory Psaltis purchased 202 Victoria Street. He had been a tenant there since 1939 and been granted a wine and spirit license for this address in 1951 when he converted the front room for use as a storeroom for wine and cigarettes. In 1966 Psaltis sold No. 202 Victoria Street to Swiss Restaurants Pty Ltd which sold the property in 1968 to Juanita Nielsen.[1]

202 Victoria Street and Juanita Nielsen: 1968–75

.jpg.webp)

Juanita_Nielsen_house.jpg.webp)

In 1968 the City of Sydney Council, then being managed by three State appointed City Commissioners, announced the preparation of a new comprehensive planning scheme. Certain key areas, such as Woolloomooloo, Potts Point and Kings Cross, were highlighted for redevelopment. Under the plans put forward, it was proposed to revitalise Kings Cross and Woolloomooloo through the demolition of old residential buildings and the construction of high density developments. Victoria Street's place in this scheme was hotly contested by residents.[1]

Also in 1968, 202 Victoria Street was sold to Juanita Joan Nielsen, journalist of Brougham Street, Potts Point who was born in 1937 and was a great-granddaughter of businessman Mark Foy. Nielsen's father bought the house for her, together with the local newspaper "NOW" which she published from 202 Victoria Street. "NOW" was originally a local issues and advertising newspaper, promoting local businesses and services and reflecting the bohemian lifestyle of Kings Cross. Initially Nielsen continued this writing style, making limited editorial comment on serious issues. Sometimes she included photographs of herself modelling the latest fashions for local stores.[1]

By mid 1973 the focus of the paper began to shift as Juanita Nielsen became involved in a number of local issues that she saw as threatening the lifestyle and harmony of the local community. One of the issues was the growing pressure by developers on the working class tenants of the terrace houses along Victoria Street to vacate their homes for demolition and redevelopment. Through 1973 and 1974 many low income tenants were forced or intimidated into leaving as the developers bought up properties. Nielsen's tenant neighbours at 204 Victoria Street were evicted to make way for demolition for the multistorey redevelopment of the site under the Parkes Development Company. Nielsen was also approached by the developers for the inclusion of her property in the development. She refused and later claimed to have been intimidated.[1]

In addition to the new focus of her newspaper, Nielsen also formed the Victoria Street Ratepayers Association and became its secretary. This enabled her to lobby the City Council against the Parkes Development and effect the delay that eventually saw the proposal lapse.[1]

Confrontation between developers and residents of Victoria Street intensified over the summer of 1973-74, often becoming violent, over the redevelopment of Victoria Point at the northern end of Victoria Street by developer Frank Theeman. Many of the tenants threatened with eviction lived in low cost rental accommodation. They organised themselves into the Victoria Street Residents Action Group to protest.[1]

In late 1973, the abduction (and later release) of one member of the Action Group, Arthur King, and the attempted eviction of one tenant, Mick Fowler, and his mother, brought matters to a head. Fowler had been away at sea when his mother was forced out. On his return from sea, and finding his mother evicted and his house boarded up, Fowler gathered members of the Seamen's Union of Australia and the Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) to gain re-entry to his house, despite the developer's security guards having been placed around it. Fowler's actions were the beginnings of an ongoing and often violent campaign between residents and unions and the developers, culminating in the BLF, led by Jack Mundey, imposing a green ban on any development on Victoria Street in late 1973, which effectively halted all work on the sites.[1]

Nielsen strongly supported the fight to save Victoria Street and the impositions of Green Bans and used her newspaper to bring attention to the battle and to the violence and menace that accompanied the struggle. The battle over the demolition and redevelopment of Victoria Street in the early 1970s was by now highly politicised and generating wider public debate as one of the main campaigns in urban conservation in Sydney during this period. Victoria Street was one of the ongoing Green Ban sites being organised by the Builders Labourers Federation. Green Bans became synonymous with urban conservation in Sydney at this time, with Kelly's Bush (Hunters Hill), Glebe, The Rocks, Woolloomooloo and Victoria Street being the main sites to be eventually protected through this process.[1]

Nielsen maintained a high media profile, despite her concern with increasing threats to her safety. She joined the Woolloomooloo Residents Action Group who were fighting similar development pressures and campaigned against development in Woolloomooloo in her paper. Her concern was primarily for the tenants of low cost rental accommodation who were being pushed out of their neighbourhoods. Interviewed by the "Sydney Morning Herald" in October 1974 she was quoted as saying 'she has no time for ratbags interested in publicity or pushing some political line, but she has real concern for the little people pushed out by developers.'[1]

In early 1975 the NSW branch of the BLF was taken over by the federal branch and the Green Ban was lifted. There were allegations that the developer Frank Theeman had met with the federal BLF leader Norm Gallagher to effect the lifting of the ban. Nielsen, however, through her activism, had by then been instrumental in organising a ban by the Federated Engine Drivers and Firemen's Association of Australasia (FEDA) which effectively continued the stop on development. Her campaign intensified and stalled the development. In April 1975 Theeman claimed that his company was losing up to $3000 a day in costs from the stalled development and was facing financial ruin.[1]

Nielsen disappeared on 4 July 1975, following an appointment at the Carousel Club in Kings Cross to discuss advertising in "NOW". Her disappearance was widely reported in the Sydney media. Her body has never been found.[1]

A 1983 coronial inquest into Nielsen's disappearance returned an open verdict. It found that Nielsen was dead but could not say how, when or where she died.[1]

In 1994 the Commonwealth Parliamentary Joint Committee on the National Crime Authority investigated Nielsen's disappearance. The Committee's report noted: 'Because of her newspaper campaign, her links with a supportive union and her position as a Victoria Street property owner and ratepayer it was possible to see Nielsen in July 1975 as one of the few significant obstacles to the plans of developers.[1]

The case remains unsolved.[1]

Description

Nos 198-202 Victoria Street, built in the late 1850s, are double storey Victorian Georgian bald-faced terraces of brick construction on sandstone footings that are built to the street alignment. The facades feature rendered brick walls in imitation ashlar.[1]

The Victoria Street terraces all have a single window and front door to the ground floor and two windows to the first floor. The windows and door feature simple drip moulds above and decorative moulded sills beneath all windows.[1]

Side gabled corrugated metal roofs with rendered brick chimneys featuring simple projecting stucco mouldings are located between No 198 and 200 and at the southern end of 202.[1]

The interior of the house has been modified over time but the original room layout is largely discernible. Significant internal fabric includes timber joinery and fireplaces.[1]

Heritage listing

The terrace house at 202 Victoria Street, Potts Point has a high level of historical and associational significance and rarity as the residence and business premises of the conservation and community activist Juanita Nielsen from 1968 until her disappearance in 1975. The house is directly associated with Nielsen's campaign for the retention of the historic streetscapes and building stock of inner city Sydney that were threatened with demolition and redevelopment in the years prior to the enactment of NSW heritage legislation. It is also a surviving example of the streetscape she was campaigning to protect.[1]

202 Victoria Street is the site where Nielsen published her local newspaper "NOW" through which she led her campaign from 1973 to 1975 against the overdevelopment of Victoria Street and Woolloomooloo. The battle for Victoria Street during the early 1970s was one of the main campaigns in urban conservation in Sydney during this period as well as being one of the ongoing Green Ban sites organised by the Builders Labourers Federation. Nielsen gave strong support to the Green Bans through the pages of "NOW" and Green Bans became synonymous with urban conservation in Sydney at this time. Victoria Street was one of the four main sites to be eventually protected through the Green Ban process.[1]

Nielsen was one of the high-profile campaigners of the early to mid 1970s in the often violent fight for tenants' rights and the protection of largely working class Victorian-era housing that characterised much of Kings Cross and Woolloomooloo. Her activism and newspaper editorials in "NOW" were instrumental in raising early public awareness of conservation issues in NSW, particularly the threat to heritage precincts, in the absence of statutory heritage protection.[1]

Nielsen's disappearance in July 1975, at the height of the campaign against tenant eviction and overdevelopment in Kings Cross and Woolloomooloo, and the subsequent allegations of foul play directed towards developers and their associates, further raised her profile and led to the exposure of criminal and underworld connections to development in Sydney's inner city areas. Nielsen's disappearance remains as one of Sydney's most enduring unsolved mysteries.[1]

Juanita Nielsen's House was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 27 June 2014 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

No 202 Victoria Street has state heritage significance as the residence and business premises of the conservation and community activist, Juanita Nielsen, and the site from which she campaigned against the overdevelopment of Kings Cross and Woolloomooloo, the destruction of the historic buildings and streetscapes and the eviction of low-income tenants of these older neighbourhoods. From this house Nielsen published her local newspaper "NOW" through which she combined, from 1973–75, steadfast championship of the inner city communities of working class tenants who were being evicted for the proposed redevelopments with opposition to the demolition of the historic housing stock, in particular the Victorian-era terraces of Victoria Street. Nielsen's campaign, through the pages of "NOW", contributed to the raising of early public awareness of conservation issues in NSW in the years preceding the enactment of NSW heritage legislation and established her profile as an early heritage campaigner of the mid 1970s.[1]

Nielsen's campaign is closely aligned with the Green Ban movement of the early 1970s. Nielsen strongly supported the Green Bans imposed by the Builders Labourer's Federation (BLF) in the early 1970s to stall development at Kelly's Bush (Hunter's Hill), The Rocks, Woolloomooloo and (in 1973), Victoria Street. When the BLF lifted its Green Bans in 1975, Nielsen worked with the Federated Engine Driver's & Fireman's Association to impose bans that effectively halted demolition for the Victoria Street redevelopment.[1]

As the site from which 'NOW was published, and the centre of Nielsen's campaign, 202 Victoria Street is a symbol of the early/mid 1970s urban conservation campaign in Sydney in which Nielsen was a key player. Nielsen's activism also ensured that No 202, scheduled for demolition in 1973, has survived as an early inner city terrace.[1]

The terraces at 198–202 Victoria Street (together with the terraces at 11–13 Earl Street) have local historical significance as workers terraces constructed in the mid nineteenth century on the first subdivisions of Edward Hallen's Telford Lodge Estate.[2][1]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of importance of cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

The terrace at 202 Victoria Street has state heritage significance for its especially strong association with the life and work of Juanita Nielsen, who owned and lived at the house from 1968 until her disappearance in July 1975. No 202 was also the building from which Nielsen ran and published "NOW", the local community newspaper Nielsen owned and wrote for from 1968 to 1975. Nielsen used "NOW" to spearhead her effective campaign, from 1973–75, against the eviction of low-income tenants and the demolition of the historic housing stock of Kings Cross and Woolloomooloo, in particular the Victorian-era terraces of Victoria Street,[1]

'NOW' started as a light, local newspaper with advertorial and commercial content, but grew into a powerful tool in Nielsen's campaign against the overdevelopment of Victoria Street and Woolloomooloo; the demolition of many of the historic terraces in the area, and the eviction of the working class tenants living in them. Through her agitation and editorial comment in "NOW", Nielsen raised the profile of the struggles in inner city Sydney against large scale developers, and revealed the often brutal and violent tactics that were being used. Nielsen was a prominent campaigner and at times she worked with unions to halt development in Victoria Street. Nielsen worked with the Builders Labourers Federation (and Jack Mundey) who were simultaneously imposing Green Bans on development in The Rocks and Woolloomooloo, and later with the Federated Engine Drivers and Firemen's Association, who effectively stopped demolition on contested sites.[1]

Nielsen left 202 Victoria Street on the morning of 4 July 1975 to keep an appointment and has never been seen since. Her disappearance and death remains as one of Sydney's most enduring mysteries. Subsequent inquiries linked this to the Kings Cross underworld and their operations in the development companies that were involved in the Victoria Street developments .[1]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

No 202 Victoria Street has local significance under this criterion.[1]

The terraces at 198–202 Victoria Street (together with the terraces at 11–13 Earl Street) have local aesthetic significance as a group of mid Victorian workers terraces, demonstrating key characteristics of the Victorian Georgian style, which contribute to the streetscapes of Victoria Street and Earl Street.[2][1]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

No 202 Victoria Street has local significance under this criterion.[1]

Through its association with Juanita Nielsen and her campaign to conserve the historic housing stock and working class community of Kings Cross and Woolloomooloo, her residence and business premises at 202 Victoria Street is regarded by local community and heritage groups as a symbol of the heritage conservation of Victoria Street and of the wider inner city area.[1]

No 202 Victoria Street is marked by a National Trust memorial plaque on the footpath commemorating Nielsen, her involvement in the fight to conserve the street and her disappearance.[1]

Nielsen is also remembered with:[1]

- a white cross over an empty grave at South Head Cemetery bearing the inscription: "A courageous journalist who vigorously fought for the rights of others and the preservation of heritage homes through her newsletter NOW";[1]

- a mural depicting the Victoria Street battles painted on one of the struts supporting the Eastern Suburbs Railway viaduct;[1]

- the annual Juanita Nielsen lecture dedicated to women activists;[1]

- the Woolloomooloo Recreation Centre opened in 1983 and named after Nielsen;[1]

- historical walking tours of the Kings Cross area that feature Juanita Nielsen.[1]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

202 Victoria Street is not considered to be significant under this criterion.[1]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

202 Victoria Street has state heritage significance as the only known building with direct and strong association with the conservation and community activist, Juanita Nielsen. Nielsen was a key figure of the mid 1970s conservation movement in the years preceding the enactment of heritage legislation in NSW for her campaign to retain the working class community and Victorian-era housing stock of the Kings Cross and Woolloomooloo areas in the face of threatened eviction, demolition and redevelopment.[1]

The five terraces at 198–202 Victoria Street and 11–13 Earl Street have local heritage significance as a rare surviving group of workers terraces within the immediate area.[2][1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

202 Victoria Street has local heritage significance as part of a terrace group that is a representative example of Victorian Georgian style workers terraces found in the inner suburbs of Sydney.[1]

See also

References

- "Juanita Nielsen's House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01929. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - Sydney LEP 2012

Bibliography

- Juanita Nielsen Vertical File.

- Rate and Assessment Books, Fitzroy Ward, 1859-1949.

- DA files 5508/51.

- Anderson, Anna (2013). "Heritage listing claim for home of campaigner Junaita Nielsen".

- City of Sydney Council (2012). "Sydney Local Environmental Plan, Item 11131, Inventory Record: Terrace Group including former house of Juanita Nielsen including interiors".

- Elizabeth Butel & Tom Thompson (1984). Kings Cross Album -- Pictorial Memories of Kings Cross, Darlinghurst, Woolloomooloo & Rushcutters Bay.

- Crook, Frank (2004). Crusading heiress paid high price for her home.

- Hawker, GN (2012). Theeman, Frank William (1913-1989). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- Hardman, M & Manning, P. Green Bans: the Story of an Australian Phenomenon.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nielsen, Juanita (1975). NOW newspapers, 30 July 1974 - 1 July 1975 (12 issues) in the Juanita Nielsen Vertical File.

- Dunn, Mark (2011). "Kings Cross".

- Dunn, Mark (2008). 202 Victoria Street Points Point - Heritage Significance Assessment.

- Meredith Burgmann & Verity Burgmann (2011). "Green Bans Movement".

- Rees, Peter (2004). Killing Juanita.

- Report by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on the National Crime Authority (1994). The National Crime Authority and James McCartney Anderson.

- Morris, Richard (2000). Nielsen, Juanita Joan (1937 - 1975). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- Morris, Richard (1996). Fowler, Jack Radnald (Mick) (1927-1979). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- Weir and Phillips (2008). Heritage Review of Selected Heritage Items and Potential Heritage Items.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Juanita Nielsen's House, entry number 1929 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 14 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Juanita Nielsen's House, entry number 1929 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 14 October 2018.

External links

![]() Media related to Juanita Nielsen's House at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Juanita Nielsen's House at Wikimedia Commons