Tribe of Judah

According to the Hebrew Bible, the tribe of Judah (שֵׁבֶט יְהוּדָה, Shevet Yehudah) was one of the twelve Tribes of Israel, named after Judah, the son of Jacob. Judah was the first tribe to take its place in the Land of Israel, occupying the southern part of the territory. Jesse and his sons, including King David, belonged to this tribe.

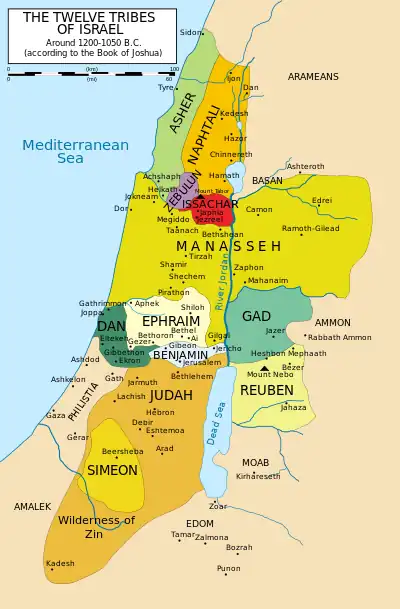

Map of the twelve tribes of Israel, before the move of Dan to the North. (The text is partially in German.) | |

| Geographical range | West Asia |

|---|---|

| Major sites | Hebron, Bethlehem |

| Preceded by | New Kingdom of Egypt |

| Followed by | Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy) |

| Tribes of Israel |

|---|

|

Biblical account

The tribe of Judah, its conquests, and the centrality of its capital in Jerusalem for the worship of Yahweh featured prominently in the Deuteronomistic history, encompassing the books of Deuteronomy through II Kings, which most scholars agree was reduced to written form, although subject to exilic and post-exilic alterations and emendations, during the reign of the Judahite reformer Josiah from 641–609 BCE.[1]

According to the account in the Book of Joshua, following a partial conquest of Canaan by the Israelite tribes (the Jebusites still held Jerusalem),[2] Joshua allocated the land among the twelve tribes. Judah's portion is described in Joshua 15[3] as encompassing most of the southern portion of the Land of Israel, including the Negev, the Wilderness of Zin and Jerusalem. However, the consensus of modern scholars is that this conquest never occurred.[4][5][6] Other scholars point to extra-biblical references to Israel and Canaan as evidence for the potential historicity of the conquest.[7][8]

In the opening words of the Book of Judges, following the death of Joshua, the Israelites "asked the Lord" which tribe should be first to go to occupy its allotted territory, and the tribe of Judah was identified as the first tribe.[9] According to the narrative in the Book of Judges, the tribe of Judah invited the tribe of Simeon to fight with them in alliance to secure each of their allotted territories. However, many scholars do not believe that the book of Judges is a reliable historical account.[10][11][12]

The Book of Samuel describes God's repudiation of a monarchic line arising from the Southern Tribe of Benjamin due to the sinfulness of King Saul, which was then bestowed onto the tribe of Judah for all time in the person of King David. In Samuel's account, after the death of Saul, all the tribes other than Judah remained loyal to the House of Saul, while Judah chose David as its king. However, after the death of Ish-bosheth, Saul's son and successor to the throne of Israel, all the other Israelite tribes made David, who was then the king of Judah, king of a re-united Kingdom of Israel. The Book of Kings follows the expansion and unparalleled glory of the United Monarchy under King Solomon. A majority of scholars believe that the accounts concerning David and Solomon's territory in the "united monarchy" are exaggerated, and a minority believe that the "united monarchy" never existed at all.[13][14][15] Disagreeing with the latter view, Old Testament scholar Walter Dietrich contends that the biblical stories of circa 10th-century BCE monarchs contain a significant historical kernel and are not simply late fictions.[16]

On the accession of Rehoboam, Solomon's son, in c. 930 BCE, the ten northern tribes under the leadership of Jeroboam from the Tribe of Ephraim split from the House of David to create the Northern Kingdom in Samaria. The Book of Kings is uncompromising in its low opinion of its larger and richer neighbor to the north, and understands its conquest by Assyria in 722 BCE as divine retribution for the Kingdom's return to idolatry.[17]

The tribes of Judah and Benjamin remained loyal to the House of David. These tribes formed the Kingdom of Judah, which existed until Judah was conquered by Babylon in c. 586 BCE and the population deported.

When the Jews returned from Babylonian exile, residual tribal affiliations were abandoned, probably because of the impossibility of reestablishing previous tribal land holdings. However, the special religious roles decreed for the Levites and Kohanim were preserved, but Jerusalem became the sole place of worship and sacrifice among the returning exiles, northerners and southerners alike.

Territory and main cities

According to the biblical account, at its height, the tribe of Judah was the leading tribe of the Kingdom of Judah, and occupied most of the territory of the kingdom, except for a small region in the north east occupied by Benjamin, and an enclave towards the south west which was occupied by Simeon. Bethlehem and Hebron were initially the main cities within the territory of the tribe.

The size of the territory of the tribe of Judah meant that in practice it had four distinct regions:

- The Negev (Hebrew: south) – the southern portion of the land, which was highly suitable for pasture.

- The Shephelah (Hebrew: lowland) – the coastal region, between the highlands and the Mediterranean sea, which was used for agriculture, in particular for grains.

- The wilderness – the barren region immediately next to the Dead Sea, and below sea level; it was wild, and barely inhabitable, to the extent that animals and people which were made unwelcome elsewhere, such as bears, leopards, and outlaws, made it their home. In biblical times, this region was further subdivided into three sections – the wilderness of En Gedi,[18] the wilderness of Judah,[19] and the wilderness of Maon.[20]

- The hill country – the elevated plateau situated between the Shephelah and the wilderness, with rocky slopes but very fertile soil. This region was used for the production of grain, olives, grapes, and other fruit, and hence produced oil and wine.

Origin

According to the Torah, the tribe consisted of descendants of Judah, the fourth son of Jacob and of Leah. Some biblical scholars view this as an etiological myth created in hindsight to explain the tribe's name and connect it to the other tribes in the Israelite confederation.[21] With Leah as a matriarch, biblical scholars regard the tribe as having been believed by the text's authors to have been part of the original Israelite confederation.[21]

Like the other tribes of the Kingdom of Judah, the tribe of Judah is entirely absent from the ancient Song of Deborah, rather than present but described as unwilling to assist in the battle between Israelites and their enemy. Traditionally, this has been explained as being due to the southern kingdom being too far away to be involved in the battle, but Israel Finkelstein et al. claim the alternative explanation that the southern kingdom was simply an insignificant rural backwater at the time the poem was written.[22]

| Judah | Aliyath | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Er | Tamar | Onan | Shelah | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Perez and Zerah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Character

Many of the Jewish leaders and prophets of the Hebrew Bible claimed membership in the tribe of Judah. For example, the literary prophets Isaiah, Amos, Habakkuk, Joel, Micah, Obadiah, Zechariah, and Zephaniah, all belonged to the tribe.[23]

The genealogies given in Matthew 1:1–6 and Luke 3:23–34 in the New Testament describe Jesus as a descendant of David, Matthew through Solomon and Luke through Nathan.[24]

Fate

As part of the Kingdom of Judah, the tribe of Judah survived the destruction of Israel by the Assyrians, and instead was subjected to the Babylonian captivity; when the captivity ended, the distinction between the tribes were lost in favour of a common identity. Since Simeon and Benjamin had been very much the junior partners in the Kingdom of Judah, it was Judah that gave its name to the identity—that of the Jews.

After the fall of Jerusalem, Babylonia (modern day Iraq), would become the focus of Jewish life for 1,000 years. The first Jewish communities in Babylonia started with the exile of the tribe of Judah to Babylon by Jehoiachin in 597 BCE as well as after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 586 BCE.[25] Many more Jews migrated to Babylon in CE 135 after the Bar Kokhba revolt and in the centuries after.[25]

The triumph or victory of "the Lion of the Tribe of Judah", who is able to open the scroll and its seven seals, forms part of the vision of the writer of the Book of Revelation in the New Testament.[26]

Ethiopia's traditions, recorded and elaborated in a 13th-century treatise, the "Kebre Negest", assert descent from a retinue of Israelites who returned with the Queen of Sheba from her visit to King Solomon in Jerusalem, by whom she had conceived the Solomonic dynasty's founder, Menelik I. Both Christian and Jewish Ethiopian tradition has it that these immigrants were mostly of the Tribes of Dan and Judah;[27] hence the Ge'ez motto Mo`a 'Anbessa Ze'imnegede Yihuda ("The Lion of the Tribe of Judah has conquered"), one of many names for Jesus of Nazareth.

See also

References

- Finkelstein, Israel (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon & Schuster. pp. 369–373. ISBN 9780743223386.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. (2003), On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, Michigan. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company) (ISBN 0-8028-4960-1)

- Joshua 15

- "Besides the rejection of the Albrightian 'conquest' model, the general consensus among OT scholars is that the Book of Joshua has no value in the historical reconstruction. They see the book as an ideological retrojection from a later period—either as early as the reign of Josiah or as late as the Hasmonean period." K. Lawson Younger Jr. (1 October 2004). "Early Israel in Recent Biblical Scholarship". In David W. Baker; Bill T. Arnold (eds.). The Face of Old Testament Studies: A Survey of Contemporary Approaches. Baker Academic. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-8010-2871-7.

- "It behooves us to ask, in spite of the fact that the overwhelming consensus of modern scholarship is that Joshua is a pious fiction composed by the deuteronomistic school, how does and how has the Jewish community dealt with these foundational narratives, saturated as they are with acts of violence against others?" Carl S. Ehrlich (1999). "Joshua, Judaism and Genocide". Jewish Studies at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, Volume 1: Biblical, Rabbinical, and Medieval Studies. Brill. p. 117. ISBN 90-04-11554-4.

- "Recent decades, for example, have seen a remarkable reevaluation of evidence concerning the conquest of the land of Canaan by Joshua. As more sites have been excavated, there has been a growing consensus that the main story of Joshua, that of a speedy and complete conquest (e.g. Josh. 11.23: 'Thus Joshua conquered the whole country, just as the LORD had promised Moses') is contradicted by the archaeological record, though there are indications of some destruction and conquest at the appropriate time. Adele Berlin; Marc Zvi Brettler (17 October 2014). The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Oxford University Press. p. 951. ISBN 978-0-19-939387-9.

- Görg, Görg. "Israel in Hieroglyphen". Biblischen Notizen. 106: 21–27."

- Frendo, Anthony (2002). "Two Long-Lost Phoenician Inscriptions and the Emergence of Ancient Israel". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 134: 37–43. doi:10.1179/peq.2002.134.1.37. S2CID 161065442.

- Judges 1:1–2

- “In any case, it is now widely agreed that the so-called ‘patriarchal/ancestral period’ is a later ‘’literary’’ construct, not a period in the actual history of the ancient world. The same is the case for the ‘exodus’ and the ‘wilderness period,’ and more and more widely for the ‘period of the Judges.’" Paula M. McNutt (1 January 1999). Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-664-22265-9.

- “The biblical text does not shed light on the history of the highlands in the early Iron I. The conquest and part of the period of the judges narratives should be seen, first and foremost, as a Deuteronomist construct that used myths, tales, and etiological traditions in order to convey the theology and territorial ideology of the late monarchic author(s) (e.g., Nelson 1981; Van Seters 1990; Finkelstein and Silberman 2001, 72–79, Römer 2007, 83–90).” Israel Finkelstein (2013). The Forgotten Kingdom: The Archaeology and History of Northern Israel (PDF). Society of Biblical Literature. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-58983-912-0.

- ”In short, the so-called ‘period of the judges’ was probably the creation of a person or persons known as the deuteronomistic historian."J. Clinton McCann (2002). Judges. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8042-3107-7.

- "Although most scholars accept the historicity of the united monarchy (although not in the scale and form described in the Bible; see Dever 1996; Na'aman 1996; Fritz 1996, and bibliography there), its existence has been questioned by other scholars (see Whitelam 1996b; see also Grabbe 1997, and bibliography there). The scenario described below suggests that some important changes did take place at the time." Avraham Faust (1 April 2016). Israel's Ethnogenesis: Settlement, Interaction, Expansion and Resistance. Routledge. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-134-94215-2.

- "In some sense most scholars today agree on a 'minimalist' point of view in this regard. It does not seem reasonable any longer to claim that the united monarchy ruled over most of Palestine and Syria." Gunnar Lebmann (2003). Andrew G. Vaughn; Ann E. Killebrew (eds.). Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period. Society of Biblical Lit. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-58983-066-0.

- "There seems to be a consensus that the power and size of the kingdom of Solomon, if it ever existed, has been hugely exaggerated." Philip R. Davies (18 December 2014). "Why do we Know about Amos?". In Diana Vikander Edelman; Ehud Ben Zvi (eds.). The Production of Prophecy: Constructing Prophecy and Prophets in Yehud. Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-317-49031-9.

- "Tracing the development of the Bible’s stories about kings from the earliest sources (now embedded in 1–2 Samuel) to the biblical books themselves, Dietrich argues that some of the stories are dated close to the time of the events they describe. His approach identifies a series of ideologies within the text, providing evidence for the development of Israelite ideas rather than grounds for dismissing the stories as fiction." Dietrich, Walter (2007). The Early Monarchy in Israel: The Tenth Century B.C.E. Translated by Joachim Vette. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Finkelstein, Israel (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon & Schuster. pp. 261–265. ISBN 9780743223386.

- 1 Samuel 24:1

- Judges 1:16

- 1 Samuel 23:24

- Jewish Encyclopedia

- Finkelstein, Israel (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon & Schuster. pp. 138–140. ISBN 9780743223386.

- TOW Project (9 December 2010). "Situating the Prophets in Israel's History". Theology of Work. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Matthew 1:1–6, Luke 3:23–31

- [מרדכי וורמברנד ובצלאל ס רותת "עם ישראל - תולדות 4000 שנה - מימי האבות ועד חוזה השלום", ע"מ 95. (Translation: Mordechai Vermebrand and Betzalel S. Ruth. "The People of Israel – the history of 4000 years – from the days of the Forefathers to the Peace Treaty", 1981, p. 95)

- Revelation 5:5

- Amos 9:7: לוא כבני כשיים אתם לי בני ישראל נאם־יהוה הלוא את־ישראל העליתי מארץ מצרים ופלשתיים מכפתור וארם מקר׃ "Are ye not as children of the Ethiopians unto me, O children of Israel? saith the LORD. Have not I brought up Israel out of the land of Egypt? and the Philistines from Caphtor, and the Syrians from Kir?"

External links

- Tribe of Judah (The Jewish Encyclopedia)

- Map of the Tribe of Judah, Adrichem, 1590. Eran Laor Cartographic Collection, The National Library of Israel.

- Map of the Tribe of Judah, Fuller, 1650. Eran Laor Cartographic Collection, The National Library of Israel.