Julius Sabinus

Julius Sabinus was an aristocratic Gaul of the Lingones at the time of the Batavian rebellion of AD 69. He attempted to take advantage of the turmoil in Rome after the death of Nero to set up an independent Gaulish state. After his defeat he was hidden for many years by his wife Epponina.

The story of the couple, with emphasis on the loyalty of Epponina (known as "Éponine"), became popular in France during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Rebellion

He was a Roman officer, naturalized, as indicated by his name. He claimed to be the great-grandson of Julius Caesar on the grounds that his great-grandmother had been Caesar's lover during the Gallic war.[1]

In AD 69, benefiting from the period of disorders which shook the Roman Empire and the rebellion started on the Rhine by the Batavians, he started a revolt in Belgian Gaul. However, his badly organised forces were easily defeated by the Sequani who were still faithful to Rome. Following his defeat, he faked his own death by telling his servants that he intended to kill himself. He then burned down the villa in which he was staying. He went into hiding in a nearby cellar, known only to his wife Epponina and a few faithful servants.

Following the failure of the revolt, the territory of Lingons was detached from Belgian Gaul, and was placed under the direct monitoring of the Roman army of the Rhine. It formed thus part of Roman province of Germania Superior.

In hiding

Epponina then lived a double-life for many years as his widow, while also on one occasion even visiting Rome with Sabinus disguised as a slave. She even gave birth to two sons by her "deceased" husband. According to Plutarch she minimised her pregnancy using an ointment that made her flesh swell, concealing her pregnancy bump. She also gave birth alone and in secret.[2]

Eventually, the deception became too obvious to continue unnoticed. In AD 78 Sabinus and Epponina were arrested and taken to Rome to be questioned by the emperor Vespasian. Her pleas for her husband were ignored. She then berated Vespasian to such an extent that he ordered her execution along with her husband. Plutarch later wrote that "In the whole of his reign no darker deed than this, none more odious in the sight of heaven, was committed."[2]

Her two sons survived. Plutarch mentions that at the time he was writing one lived in Delphi and the other had recently been killed in Egypt (possibly in the Kitos War).[2]

Cultural references

The modernised French version of Epponina's name, Éponine, became familiar in revolutionary France, because of its connotations of wifely virtue, patriotism and anti-imperialism. Voltaire speaks of Plutarch's "magnificent praise for the virtue of Eponine.”[3] Even before the revolution there were several French works about Sabinus and Éponine. Michel-Paul-Gui de Chabanon's tragedy Éponine was performed in 1762. It formed the basis for Sabinus, an opera in five acts composed by François-Joseph Gossec, premiered at Versailles on 4 December 1773.[4] After the revolution Eponine et Sabinus (1796) was performed at the Lycée theatre.[5] De Lisle de Salles' novel Éponine led to his imprisonment during the Reign of Terror, as it was interpreted as an attack on the Committee of Public Safety.[6]

In his novel Les Misérables, the French author Victor Hugo used the name for Éponine, a character who also aspires to die with her own beloved in a revolution. Epponina also appears as "Éponine" in Baudelaire's poem Little old Ladies from Les Fleurs du Mal in a verse dedicated to Hugo:

These dislocated wrecks were women once,

Were Eponine or Laïs! hunchbacked freaks,

Though broken let us love them! they are souls.[7]

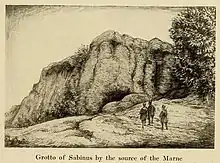

There were several paintings of the couple, including works by Nicolas-André Monsiau and Etienne Barthélémy Garnier. These usually depict them hiding in a cave, a reference to a myth that a cave near Langres was the place in which Sabinus had hidden. It is still locally known as "Sabinus' cave" (Grotte de Sabinus). Joseph Mills Hanson, who visited it shortly after World War I, described it as a "cave in the rock having two entrances, the one looking south, the other east. The interior is very irregular in outline but it is perhaps fifty feet deep, twenty feet wide, and seven feet high. Near the east entrance is a rough pillar, left evidently by the cutting away of the surrounding stone." A statue of the Virgin Mary was placed there, along with graffiti left by American soldiers in the war.[8]

References

- Tacitus, Histories 4.55

- Plutarch, On Lovers.

- Catherine Clément and Julia, Kristeva (Jane Marie Todd, trans), The Feminine and the Sacred, Columbia University Press, New York, 2001, p.45.

- Spire Pitou, The Paris Opera: An Encyclopedia of Operas, Ballets, Composers, and Performers, Volume: 1, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 1983, p.481.

- Emmet Kennedy et al, Theatre, Opera, and Audiences in Revolutionary Paris: Analysis and Repertory, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 1996, pp 276; 377.

- P H Ditchfield, Books Fatal to Their Authors, Echo Library, 200, p.40.

- James McGowan (trans), Charles Baudelaire, The Flowers of Evil, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1998, p.371.

- Joseph Mills Hanson, The Marne, historic and picturesque, McClurg, 1922, p.9.