Symphony No. 41 (Mozart)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart completed his Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551, on 10 August 1788.[1] The longest and last symphony that he composed, it is regarded by many critics as among the greatest symphonies in classical music.[2][3] The work is nicknamed the Jupiter Symphony, probably coined by the impresario Johann Peter Salomon.[4]

| Symphony No. 41 | |

|---|---|

| Jupiter | |

| by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | |

Mozart c. 1788 | |

| Key | C major |

| Catalogue | K. 551 |

| Composed | 1788 |

| Movements | 4 |

The autograph manuscript of the symphony is preserved in the Berlin State Library.

Instrumentation

The symphony is scored for Flute, 2 Oboes, 2 Bassoons, 2 Horns in C and F, 2 Trumpets in C, Timpani in C and G, First and Second Violins, Violas, Cellos and Double Basses.

Composition and premiere

Symphony No. 41 is the last of a set of three that Mozart composed in rapid succession during the summer of 1788. No. 39 was completed on 26 June and No. 40 on 25 July.[1] Nikolaus Harnoncourt argues that Mozart composed the three symphonies as a unified work, pointing, among other things, to the fact that the Symphony No. 41, as the final work, has no introduction (unlike No. 39) but has a grand finale.[5]

Around the same time as he composed the three symphonies, Mozart was writing his piano trios in E major (K. 542), and C major (K. 548), his piano sonata No. 16 in C (K. 545) – the so-called Sonata facile – and a violin sonatina K. 547.

It is not known of a certainty whether Symphony No. 41 was ever performed in the composer's lifetime. According to Otto Erich Deutsch, around this time Mozart was preparing to hold a series of "Concerts in the Casino" in a new casino in the Spiegelgasse owned by Philipp Otto. Mozart even sent a pair of tickets for this series to his friend Michael Puchberg. Historians have not determined whether the concert series was held, or was cancelled for lack of interest.[1] However, the new symphony in C was performed in the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1789- at least according to its concert program.

Movements

The four movements are arranged in the traditional symphonic form of the Classical era:

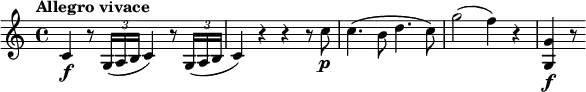

- Allegro vivace, 4

4 - Andante cantabile, 3

4 in F major - Menuetto: Allegretto – Trio, 3

4 - Molto allegro, 2

2

The symphony typically has a duration of about 33 minutes.

I. Allegro vivace

The sonata form first movement's main theme begins with contrasting motifs: a threefold tutti outburst on the fundamental tone (respectively, by an ascending motion leading in a triplet from the dominant tone underneath to the fundamental one), followed by a more lyrical response.

This exchange is heard twice and then followed by an extended series of fanfares. What follows is a transitional passage where the two contrasting motifs are expanded and developed. From there, the second theme group begins with a lyrical section in G major which ends suspended on a seventh chord and is followed by a stormy section in C minor. Following a full stop, the expositional coda begins which quotes Mozart's insertion aria "Un bacio di mano", K. 541 and then ends the exposition on a series of fanfares.[6]

The development begins with a modulation from G major to E♭ major where the insertion-aria theme is then repeated and extensively developed. A false recapitulation then occurs where the movement's opening theme returns but softly and in F major. The first theme group's final flourishes then are extensively developed against a chromatically falling bass followed by a restatement of the end of the insertion aria then leading to C major for the true recapitulation.[6] With the exception of the usual key transpositions and some expansion of the minor key sections, the recapitulation proceeds in a regular fashion.[6]

II. Andante cantabile

The second movement, also in sonata form, is a sarabande of the French type in F major (the subdominant key of C major) similar to those found in the keyboard suites of J.S. Bach.[6] This is the only symphonic slow movement of Mozart's to bear the indication cantabile. The opening melody, played by muted violins, is never allowed to conclude without interruption. A secondary development section disrupts the recapitulation with rhythmic figures.[7]

III. Menuetto: Allegretto – Trio

The third movement, a menuetto marked "allegretto" is similar to a Ländler, a popular Austrian folk dance form. Midway through the movement there is a chromatic progression in which sparse imitative textures are presented by the woodwinds (bars 43–51) before the full orchestra returns. In the trio section of the movement, the four-note figure that will form the main theme of the last movement appears prominently (bars 68–71), but on the seventh degree of the scale rather than the first, and in a minor key rather than a major, giving it a very different character.

This movement was later arranged and covered by Mike Batt as The Wombles, released as a single in October 1974 and spending nine weeks in the UK singles chart, peaking at number 16. [8] Batt went on to conduct the LSO, Royal Philharmonic, London Philharmonic, Sydney Symphony and Stuttgart Philharmonic orchestras.

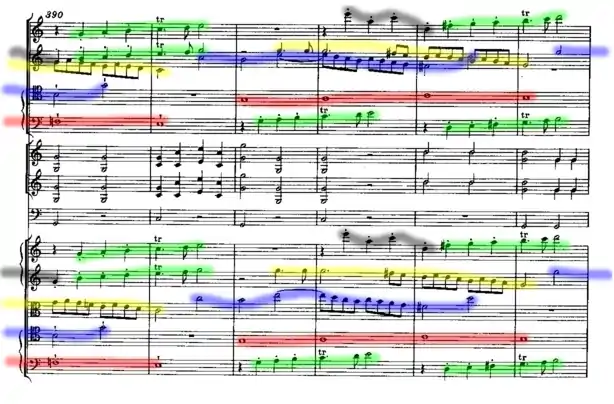

IV. Molto allegro

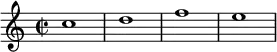

Finally, a distinctive characteristic of this symphony is the five-voice fugato (representing the five major themes) at the end of the fourth movement. But there are fugal sections throughout the movement either by developing one specific theme or by combining two or more themes together, as seen in the interplay between the woodwinds. The main theme consists of four notes:

Four additional themes are heard in the "Jupiter's" finale, which is in sonata form, and all five motifs are combined in the fugal coda.

In an article about the Jupiter Symphony, Sir George Grove wrote that "it is for the finale that Mozart has reserved all the resources of his science, and all the power, which no one seems to have possessed to the same degree with himself, of concealing that science, and making it the vehicle for music as pleasing as it is learned. Nowhere has he achieved more." Of the piece as a whole, he wrote that "It is the greatest orchestral work of the world which preceded the French Revolution."[9]

The four-note theme is a common plainchant motif which can be traced back at least as far as Thomas Aquinas's "Pange lingua gloriosi corporis mysterium" from the 13th century.[10] It was very popular with Mozart. It makes a brief appearance as early as his Symphony No. 1 in 1764. Later, he used it in the Credo of an early Missa Brevis in F major, the first movement of his Symphony No. 33 and trio of the minuet of this symphony.[11] It also appears in the first movement of the violin sonata K481 as the basis for the development section.

Scholars are certain Mozart studied Michael Haydn's Symphony No. 28 in C major, which also has a fugato in its finale and whose coda he very closely paraphrases for his own coda. Charles Sherman speculates that Mozart also studied Michael Haydn's Symphony No. 23 in D major because he "often requested his father Leopold to send him the latest fugue that Haydn had written."[12] The Michael Haydn No. 39, written only a few weeks before Mozart's, also has a fugato in the finale, the theme of which begins with two whole notes. Sherman has pointed out other similarities between the two almost perfectly contemporaneous works. The four-note motif is also the main theme of the contrapuntal finale of Michael's elder brother Joseph's Symphony No. 13 in D major (1764).

Origin of the nickname

According to Franz Mozart, Wolfgang's younger son, the symphony was given the name Jupiter by Johann Peter Salomon,[4][13] who had settled in London in around 1781. The name has also been attributed to Johann Baptist Cramer, an English music publisher.[14][15][16] Reportedly, from the first chords, Mozart's Symphony No. 41 reminded Cramer of Jupiter and his thunderbolts.[16]

The Times of Thursday, May 8, 1817, carries an advertisement for a concert to be given in the Hanover Square Rooms on "Friday next, May 9" to include "Grand Sinfonie (Jupiter), Mozart". The Morning Post of Tuesday, June 3, 1817, carries an advertisement for printed music that includes: "The celebrated movement from Mozart's sympathy [sic], called 'Jupiter', arranged as a Duet, by J. Wilkins, 4s. [4 shillings]".

Responses and reception

In a phrase ascribed to musicologist Elaine Sisman in a book devoted to the "Jupiter" (Cambridge Musical Handbooks, 1993), most responses ranged "from admiring to adulatory, a gamut from A to A."[17]

As summarized below, the Symphony garnered approbation from critics, theorists, composers and biographers and came to be viewed as a canonized masterwork, known for its fugue and its overall structure, which exuded clarity.[18]

- E. L. Gerber in Neues Historisch-biographisches Lexicon der Tonkünstler (1812–1814): "...overpoweringly great, fiery, artistic, pathetic, sublime, Symphony in C ... we would already have to perceive him as one of the first[-ranked] geniuses of modern times and the century just past"[18]

- A review in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (1846): "How pure and clear are all the images within! No more and no less than that which each requires according to its nature. ... Here is revealed how the master first collects his material separately, then explores how everything can proceed from it, and finally builds and elaborates upon it. That even Beethoven worked this way is revealed in his sketchbooks."[19]

- Brahms remarked in 1896: "I am able to understand too that Beethoven's first symphony did impress people colossally. But the last three symphonies by Mozart are much more important. Some people are beginning to feel that now."[20]

First recording

The first known recording of the Jupiter Symphony is from around the beginning of World War I, issued by the Victor Talking Machine Company in its black label series, making it one of the first symphonies to be recorded using the acoustic recording technology.[21]

The record labels list the Victor Concert Orchestra as the performers; they omit the conductor, who according to company ledgers was Walter B. Rogers.[22]

The music was heavily abridged, issued on two records: 10-inch 17707 and 12-inch 35430. Victor published two widely separated takes of each of the first two movements under the same catalogue numbers. The distribution, recording dates, and approximate timings were as follows (data from corresponding matrix pages in Discography of American Historical Recordings as indicated and physical copies of the records):

1st movement (17707-A, 10") 8/5/1913 (if take 1) or 1/27/1915 (if take 6) 2:45[23]

2d movement (35430-A, 12") 8/5/1913 (if take 1) or 1/18/1915 (if take 7) 3:32[24]

3d movement (17707-B, 10") 12/22/1914 2:40[25]

4th movement (35430-B, 12") 12/22/1914 3:41[26]

See also

- Beim Auszug in das Feld – Elaine Sisman's theory that the flourishes of military music in the work were inspired by the outbreak of the Austro-Turkish War of 1788–91.

References

- Deutsch 1965, 320

- Brown, Mark (August 4, 2016). "Beethoven's Eroica voted greatest symphony of all time". The Guardian. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

Mozart's last symphony, No. 41, the 'Jupiter', was in third place

- "These are factually the 10 best symphonies of all time". Classic FM (UK). August 30, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- Heartz 2009, pp. 210, 458, 474

- Clements, Andrew (23 July 2014). "Mozart: The Last Symphonies review – a thrilling journey through a tantalising new theory". The Guardian.

- Brown, A. Peter, The Symphonic Repertoire (Volume 2). Indiana University Press (ISBN 0-253-33487-X), pp. 423–32 (2002).

- Sisman 1993, pp. 55–63, chapter Structure and expression: Andante cantabile.

- Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 608. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- Grove 1906.

- William Klenz: "Per Aspera ad Astra, or The Stairway to Jupiter"; The Music Review, Vol. 30, Nr. 3, August 1969, pp. 169–210.

- Heartz 2009, pp. 212–215.

- C. Sherman, Foreword to score of Sinfonia in C, Perger 31 Vienna: Doblinger K. G. (1967)

- Latham, Alison (2002). "'Jupiter' Symphony". The Oxford companion to music. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957903-7. OCLC 59376677.

- Burk, J. N. (1959). "Symphony No. 41, in C Major ('Jupiter'), K. 551". In: Mozart and His Music, p. 299.

- F. G. E. [Frederick George Edwards] (1 October 1902). "J. B. Cramer (1771–1858)". The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. 43 (716): 641–646. doi:10.2307/3369624. JSTOR 3369624. (spec. p. 644 (para. 2)

- Lindauer, David. (2006, January 25). "Annapolis Symphony Orchestra (ASO) Concert Part of Mozart Birthday Tribute", The Capital (Annapolis, Maryland), p. B8.

- "Symphony No. 41 in C Major, "Jupiter"". The Kennedy Center. Archived from the original on 2017-03-02. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Sisman 1993, p. 28.

- Russell 2017.

- Sisman 1993, p. 30.

- "Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Discography of American Historical Recordings".

- "Mozart – Jupiter Symphony". Discography of American Historical Recordings.

- "Victor matrix B-13669. Jupiter symphony / Victor Concert Orchestra". Discography of American Historical Recordings.

- "Victor matrix C-13671. Jupiter symphony / Victor Concert Orchestra". Discography of American Historical Recordings.

- "Victor matrix B-13670. Jupiter symphony / Victor Concert Orchestra". Discography of American Historical Recordings.

- "Victor matrix C-13677. Jupiter symphony / Victor Concert Orchestra". Discography of American Historical Recordings.

Sources

- Deutsch, Otto Erich (1965). Mozart: A Documentary Biography. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Grove, George (January 1906). "Mozart's Symphony in C (The Jupiter)". The Musical Times. 47 (755): 27–31. doi:10.2307/904183. JSTOR 904183.

- Heartz, Daniel (2009). Mozart, Haydn and Early Beethoven 1781–1802. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06634-0.

- Russell, Peter (2017-09-04). Delphi Masterworks of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. ISBN 978-1-78656-120-6.

- Sisman, Elaine R. (1993). Mozart: The 'Jupiter' Symphony. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40924-1.

Further reading

- Konrad, Ulrich (2005). "Commentary". In Ulrich Konrad (ed.). Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Sinfonie in C, KV 551 Jupiter. Autograph Score. Facsimile. Commentary. Kassel: Bärenreiter. pp. 9–25. ISBN 3-7618-1824-6.

External links

- Symphony in C Major, K. 551. Mozart's autograph in the Berlin State Library

- Sinfonie in C (Jupiter-Sinfonie) KV 551: Score and critical report (in German) in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe

- Symphony No. 41: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Analysis of the last movement of the symphony