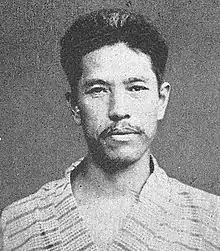

Kōzaburō Tachibana

Kōzaburō Tachibana (橘 孝三郎, Tachibana Kōzaburō, 18 March 1893 – 30 March 1974) was a Japanese political activist and ultra-nationalist.

Early life

Tachibana came from a samurai family, although his father was a fabric merchant.[1]

During his time of higher education, his ideals of politics emerged. Deriving from the thoughts of Tolstoi, Gandhi, Kita Ikki and Western socialism, he developed the thought of agrarian,[2] radical humanism and anti-capitalistic ideas.[3] He argued that radical, violent change was needed to cleanse ‘the world of national politics...poisoned by mammon and the gang of corrupt industrialists’.[4]

Political action

In the 1920s and 1930s, he sought have direct and violent action against the existing government. By inspiring sympathetic and young officers, they conspired together to arrange the assassination of Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi during the May 15 Incident.[5] Tachibana was sentenced to life imprisonment.[6] In 1934, his sentence was reduced to 20 years in an amnesty.[7] Tachibana was released from prison in 1940.[3] He met Aikido founder Morihei Ueshiba during this time period.

He was also involved in the bombing attacks on the Seiyūkai headquarters, one of the leading political parties at the time, and on the Mitsui Bank in Tokyo.

Political beliefs

Tachibana, noted to be a romantic and Utopian thinker, his primary aim was to "liberate the people" from a false governance. During a time where Western concepts such as capitalism globalized the Japanese markets, the rural villages were forced to adapt to this rapid change of increasing goods, causing the destruction of the conventional community life. This caused the privileged classes and political parties to rob Japan of its basic principles such as social existence. Therefore, Tachibana believed that for the development of the Asian and Western societies, the village community was the original starting point of civilization and the only way for the country to prosper.

Tachibana called for the formation of a "patriotic brotherhood" to unselfishly lay down their lives to save the people in accordance to the emperor's wishes. Wanting to recruit form all social classes, the brotherhood would represent a more perfect whole, signified by the imperial will.[8]

References

- The American Asian Review. Institute of Asian Studies, St. John's University. 1988. p. 18.

- Sources of Japanese Tradition, Abridged: Part 2: 1868 to 2000. Columbia University Press. 13 August 2013. pp. 269–. ISBN 978-0-231-51815-4.

- David Ernest Apter; Nagayo Sawa (1984). Against the State: Politics and Social Protest in Japan. Harvard University Press. pp. 67–. ISBN 978-0-674-00921-9.

- Conrad Totman, History of Japan (2000), p.371

- David E. Kaplan; Alec Dubro (2012). Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld. University of California Press. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-520-27490-7.

- Contemporary Japan. Foreign Affairs Association of Japan. 1964. p. 377.

- "Amnesty of 1934". The Cincinnati Enquirer. 1934-02-11. p. 18. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- Wakabayashi, Bob T. (1998). Modern Japanese thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-62606-7. OCLC 857275236.