Kadamba dynasty

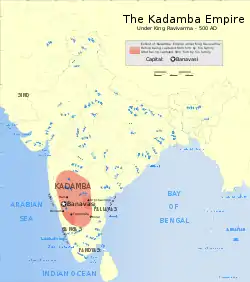

The Kadambas (345–540 CE) were an ancient royal family of Karnataka, India, that ruled northern Karnataka and the Konkan from Banavasi in present-day Uttara Kannada district. The kingdom was founded by Mayurasharma in c. 345, and at later times showed the potential of developing into imperial proportions. An indication of their imperial ambitions is provided by the titles and epithets assumed by its rulers, and the marital relations they kept with other kingdoms and empires, such as the Vakatakas and Guptas of northern India. Mayurasharma defeated the armies of the Pallavas of Kanchi possibly with the help of some native tribes and claimed sovereignty. The Kadamba power reached its peak during the rule of Kakusthavarma.

Kadambas of Banavasi Banavasi Kadambaru | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 345 CE–540 CE | |||||||||||

Extent of Kadamba Empire, 500 CE | |||||||||||

| Status | Empire (Subordinate to Pallava until 345) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Banavasi | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Sanskrit Kannada | ||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism Jainism[1][2] | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||||

• 345–365 | Mayurasharma | ||||||||||

• 516-540 | Krishna Varma II | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Earliest Kadamba records | 450 CE | ||||||||||

• Established | 345 CE | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 540 CE | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||||

| Kadamba dynasty |

|---|

_at_Talagunda.JPG.webp)

The Kadambas were contemporaries of the Western Ganga Dynasty and together they formed the earliest native kingdoms to rule the land with autonomy. From the mid-6th century the dynasty continued to rule as a vassal of larger Kannada empires, the Chalukya and the Rashtrakuta empires for over five hundred years during which time they branched into minor dynasties. Notable among these are the Kadambas of Goa, the Kadambas of Halasi and the Kadambas of Hangal. During the pre-Kadamba era the ruling families that controlled the Karnataka region, the Mauryas and later the Satavahanas, were not natives of the region and therefore the nucleus of power resided outside present-day Karnataka. The Kadambas were the first indigenous dynasty to use Kannada, the language of the soil, at an administrative level. In the History of Karnataka, this era serves as a broad-based historical starting point in the study of the development of the region as an enduring geo-political entity and Kannada as an important regional language.

History

Origin

_and_Hoysala_king_Veera_Ballala_II_(c.1196)_in_the_open_mantapa_of_the_Tarakeshwara_temple_at_Hangal.JPG.webp)

There are several legends regarding the origin of the Kadambas. According to one such legend the originator of this dynasty was a three-eyed four-armed warrior called Trilochana Kadamba (the father of Mayurasharma) who emerged from the sweat of the god Shiva under a Kadamba tree. Another legend tries to simplify it by claiming Mayurasharma himself was born to Shiva and Bhudevi (goddess of the earth). Other legends tie them without any substance to the Nagas, and the Nandas of northern India.[3] An inscription of c. 1189 claims that Kadamba Rudra, the founder of the kingdom, was born in a forest of Kadamba trees. As he had "peacock feather"-like reflections on his limbs, he was called Mayuravarman.[4] From the Talagunda inscription, one more legend informs that the founding king of the dynasty, Mayurasharma was anointed by "the six-faced god of war Skanda".[5]

Historians are divided on the issue of the geographical origin of the Kadambas, whether they were of local origin or earlier immigrants from northern India.[6] The social order (caste) of the Kadamba family is also an issue of debate, whether the founders of the kingdom belonged to the Brahmin caste as described by the Talagunda inscription, or of local tribal origin. Historians Chopra et al. claim the Kadambas were none other than the Kadambu tribe who were in conflict with the Chera kingdom (of modern Kerala) during the Sangam era. The Kadambus find mention in the Sangam literature as totemic worshipers of the Kadambu tree and the Hindu god Subramanya. According to R.N. Nandi, since the inscription states the family got its name by tending to the totem tree that bore the beautiful Kadamba flowers, it is an indication of their tribal origin.[7][8] However the historians Sastri and Kamath claim the family belonged to the Brahmin caste, believed in the Vedas and performed Vedic sacrifices. According to the Talagunda and the Gudnapur inscriptions, they belonged to the Manavya Gotra and were Haritiputrās ("descendants of Hariti lineage"), which connected them to the native Chutus of Banavasi, a vassal of the Satavahana empire and the Chalukyas who succeeded them.[9][10][11] According to Rao and Minahan, being native Kannadigas, the Kadambas promptly gave administrative and political importance to their language Kannada after coming to power.[12][13]

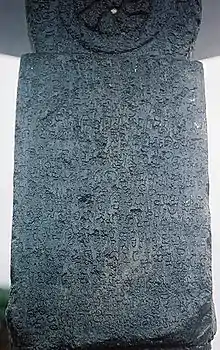

Birth of Kingdom

One of their earliest inscriptions, the Talagunda inscription of crown prince Santivarma (c. 450) gives what may be the most possible cause for the emergence of the Kadamba kingdom. It states that Mayurasharma was a native of Talagunda, (in present-day Shimoga district of Karnataka state) and his family got its name from the Kadamba tree that grew near his home.[14] The inscription narrates how Mayurasharma proceeded to Kanchi in c. 345 along with his guru and grandfather Veerasharma to pursue his Vedic studies at a Ghatika ("school"). There, owing to some misunderstanding between him and a Pallava guard or at an Ashvasanstha ("horse sacrifice"), a quarrel arose in which Mayurasharma was humiliated. Enraged, the Brahmin discontinued his studies, left Kanchi swearing vengeance on the Pallavas and took to arms. He collected a faithful group of followers, routed the Pallava armies and Antarapalas (frontier guards) and firmly rooted himself in the dense forests of the modern Srisailam (Sriparvata) region. After a prolonged period of low intensity warfare against the Pallavas and other smaller kings such as the Brihad-Banas of Kolar region, he was able to levy tributes from the Banas and other kingdoms and finally proclaimed independence. According to Indologist Lorenz Franz Kielhorn who deciphered the Talagunda inscription, unable to contain Mayurasharma the Pallavas under king Skandavarman had to accept his sovereignty between the Arabian Sea (known as Amara or Amarawa) to Premara or Prehara which could be interpreted as either ancient Malwa in central India or the Tungabhadra or Malaprabha region in central Karnataka. According to the historian and epigraphist M. H. Krishna Iyengar a fragmentary inscription of Mayurasharma at Chandravalli which pertains to a water reservoir contained the names of Abhiras and Punnatas, two contemporary kingdoms who ruled as the northern and southern neighbors of Mayurasharma's Kadamba kingdom.[15][16][17] The Talagunda inscription also confirms Mayurasharma was the progenitor of the kingdom.[18][19][20] The inscription gives a graphic description of the happenings after the Kanchi incident:

That the hand dexterous in grasping the Kusha grass,

fuel and stones, ladle, melted butter and the oblation vessel,

unsheathed a flaming sword, eager to conquer the earth[15]

Thus, according to Ramesh, in an act of righteous indignation was born the first native kingdom of Karnataka, and the Pallava King Skandavarman condescended to recognize the growing might of the Kadambas south of the Malaprabha river as a sovereign power.[21][16] Majumdar however feels even an inscription as important as the Talagunda pillar inscription leaves many a detail unanswered.[22] Scholars such as Moraes and Sastri opine that Mayurasharma may have availed himself of the confusion in the south that was created by the invasion of Samudragupta who in his Allahabad inscription claims to have defeated Pallava King Vishnugopa of Kanchi. Taking advantage of the weakening of the Pallava power, Mayurasharma appears to have succeeded in establishing a new kingdom.[4] According to epigraphist M.H. Krishna, Mayurasharma further subdued minor rulers such as the Traikutas, the Abhiras, the Pariyathrakas, the Shakasthanas, the Maukharis, the Punnatas and the Sendrakas.[23] The fact that Mayurasharma had to travel to distant Kanchi for Vedic studies gives an indication that Vedic lore was quite rudimentary in the Banavasi region at that time. The Gudnapur inscription which was discovered by epigraphist B.R. Gopal states that Mauryasharma, whose grandfather and preceptor was Veerasharma and his father was Bandhushena, developed the character of a Kshatriya (warrior caste).[24][23][20] Sen feels the successor of Mayurasharma, Kangavarma changed his surname from "Sharma" to "Varma".[16]

Expansion

Mayurasharma was succeeded by his son Kangavarma in c. 365. He had to fight the Vakataka might to protect his kingdom (also known as Kuntala country). According to Jouveau-Dubreuil he was defeated by the King Prithvisena but managed to maintain his freedom. Majumdar feels Kangavarma battled with King Vidyasena of the Basin branch of the Vakataka kingdom with no permanent results.[25][26][27] His son Bhageerath who came to power in c. 390 is said to have retrieved his fathers losses. According to Kamath, the Talagunda inscription describes Bhageerath as the sole "lord of the Kadamba land" and the "great Sagara" (lit, "great Ocean") himself indicating he may have retrieved their losses against the Vakatakas. But contemporary though Vakataka inscriptions do not confirm this.[25][16][20] His son Raghu died fighting the Pallavas in c. 435 though some inscriptions claim he secured the kingdom for his family. He was succeeded by his younger brother Kakusthavarma in c. 435. Kakusthavarma was the most powerful ruler of the dynasty. According to Sastri and Moraes, under the rule of Kakusthavarma, the kingdom reached its pinnacle of success and the Talagunda record calls him the "ornament of the family". The Halasi and Halmidi inscriptions also hold him in high esteem.[25][28][20][29]

From the Talagunda inscription it is known that he maintained marital relations with even such powerful ruling families as the imperial Guptas of the northern India. One of his daughters was married to King Madhava of the Ganga dynasty. According to the Desai one of his daughters was married to Kumara Gupta's son Skanda Gupta (of the Gupta dynasty), and from Balaghat inscription of Vakataka king Prithvisena we know another daughter called Ajitabhattarika was married to the Vakataka prince Narendrasena.[30][28][16][31][29] He maintained similar relations with the Bhatari vassal and the Alupas of South Canara. According to Desai and Panchamukhi evidence from Sanskrit literature indicates that during this time the notable Sanskrit poet Kalidasa visited the Kadamba court. Moraes and Sen feel the visit happened during the reign of Bhageerath. According to Sen, Kalidasa was sent by Chandragupta II Virakmaditya to conclude a marriage alliance with the Kadambas.[30][32][16]

His successor Santivarma (c. 455) was known for his personal charm and beauty. According to an inscription he wore three crowns (pattatraya) to display his prosperity, thus "attracting the attention of his enemies", the Pallavas. When the Pallava threat loomed, He divided his kingdom in c. 455 and let his younger brother Krishnavarma rule over the southern portion and deal with the Pallavas. The branch is called the Triparvata branch and ruled from either Devagiri in the modern Dharwad district or Halebidu. Majumdar considers Krishnavarma's rule as somewhat obscure due to lack of his inscriptions though the records issued by his sons credit him with efficient administration and an ashvamedha (horse sacrifice). It is known that he possibly lost his life in battle with the Pallavas. According to the Hebbatta record his successor and son Vishnuvarma had to accept the suzerainty of the Pallavas despite showing initial allegiance to his uncle Santivarma ruling from Banavasi whom he described in an earlier record as "lord of the entire Karnata country".[33][28][34] In c. 485, his son Simhavarma came to power but maintained a low profile relationship with Banavasi. In the northern part of the kingdom (the Banavasi branch), Santivarma's brother Shiva Mandhatri ruled from c. 460 for more than a decade. In c. 475 Santivarma's son Mrigeshavarma came to the throne and faced the Pallavas and Gangas with considerable success. The Halasi plates describes him the "destroyer of the eminent family of the Gangas" and the "destructive fire" (pralayaanala) to the Pallavas. His queen Prabhavati of the Kekaya family bore him a son called Ravivarma. Mrigeshavarma was known to be a scholar and an expert in riding horses and elephants.[28][34][35]

After Kakusthavarma only Ravivarma (c. 485) was able to build the kingdom back to its original might during a long rule lasting up to c. 519.[28][20] Numerous inscriptions from his rule, starting from fifth up to the thirty-fifth regnal years give a vivid picture of his successes which was marked by a series of clashes within the family, and also against the Pallavas and the Gangas. He is credited with a victory against the Vakatakas as well. Historian D. C. Sircar interprets Ravivarma's Davanagere record dated c. 519 (king's last regnal year) and claims that the king's suzerainty extended over the whole of South India as far as the Narmada river in the north and that the people of these lands sought his protection. Ravivarma donated land to a Buddhist Sangha (temple) in his 34th regnal year in c. 519 to the south of the Asandi Bund (Setu) which showed his tolerance and encouragement of all faiths and religions.[36][37][38] A Mahadeva temple constructed during his rule finds mention in a Greek writing of the period. According to the Gudnapur inscription, lesser rulers such as the Punnatas, the Alupas, the Kongalvas and the Pandyas of Uchangi were dealt with successfully. The crux of the kingdom essentially consisted of significant areas of the deccan including large parts of modern Karnataka. King Ravivarma of the Banavasi branch killed king Vishnuvarma of the Triparvata branch according to Moraes and successfully dealt with a rebelling successors of Shiva Mandhatri at Ucchangi. The Pallava king Chandadanda (another name for Pallava king Santivarman) also met the same fate according to Sathianathaier. Ravivarma left two of his brothers, Bhanuvarma and Shivaratha to govern from Halasi and Ucchangi.[39][40]

Decline

After Ravivarma's death, he was succeeded by his peaceful son Harivarma in c. 519 according to the Sangolli inscription. According to the Bannahalli plates, Harivarma was killed by a resurgent Krishnavarma II (son of Simhavarma) of the Triparvata branch around c. 530 when he raided Banavasi, thus uniting the two branches of the kingdom.[40] Around c. 540 the Chalukyas who were vassals of the Kadambas and governed from Badami conquered the entire kingdom. The Kadambas thereafter became vassals of the Badami Chalukyas.[41][28][20][42] In later centuries, the family fragmented into numerous minor branches and ruled from Goa, Halasi, Hangal, Vainad, Belur, Bankapura, Bandalike, Chandavar and Jayantipura (in Odisha).[43] That the Kadambas of Banavasi were a prosperous kingdom is attested to by the famous Aihole inscription of the Chalukyas which describes Banavasi in these terms:

Resembling the city of gods and a girdle of swans

playing on the high waves of the river Varada[44]

Administration

_of_King_Kamadeva_of_the_Kadamba_dynasty_of_the_Hangal_branch.jpg.webp)

The Kadamba kings, like their predecessors the Satavahanas, called themselves Dharmamaharajas (lit, "Virtuous kings") and followed them closely in their administrative procedures. The kings were well read and some were even scholars and men of letters. Inscriptions describe the founding king Mayurasharma as "Vedangavaidya Sharada" ("master of the Vedas"), Vishnuvarma was known for his proficiency in grammar and logic, and Simhavarma was called "skilled in the art of learning".[45][46]

This wisdom and knowledge from the ancient Hindu texts called (the Smritis) provided guidance in governance. Mores identified several important positions in the government: the prime minister (Pradhana), steward of household (Manevergade), secretary of council (Tantrapala or Sabhakarya Sachiva), scholarly elders (Vidyavriddhas), physician (Deshamatya), private secretary (Rahasyadhikritha), chief secretary (Sarvakaryakarta), chief justice (Dharmadhyaksha) above whom was the king himself, other officials (Bhojaka and Ayukta), revenue officers (Rajjukas) and the writers and scribes (Lekhakas). The Gavundas formed the elite land owners who were the intermediaries between the king and the farmers collecting taxes, maintaining revenue records and providing military support to the royal family.[47] The army consisted of officers such as Jagadala, Dandanayaka and Senapathi. The organization was based on the strategy called "Chaurangabala". Guerrilla warfare was not unknown and may have been used often to gain tactical advantage.[48][46]

A crown prince (Yuvaraja) from the royal family often helped the king in central administration at the royal capital. Some governed in the far off provinces. This experience not only provided future security and know-how for the king to be, but also kept administration controls within trusted family members. This is seen in the case of kings Shantivarma, Kakusthavarma and Krishnavarma. King Kakusthavarma had appointed his son Krishnavarma as viceroy of Triparvatha region. King Ravivarma's brothers Bhanu and Shivaratha governed over Halasi and Uchangi provinces respectively. Some regions continued to be under hereditary ruling families such as the Alupas, the Sendrakas, the Kekeyas and the Bhataris. While Banavasi was the nerve center of power, Halasi, Triparvata and Uchangi were important regional capitals.[49][46] The kingdom was divided into provinces (Mandalas or Desha). Under a province was a district (Vishayas), nine of which have been identified by Panchamukhi. Under a district was a Taluk (Mahagramas) comprising numerous villages under which were the villages in groups of ten (Dashagrama). The smallest unit was the village (Grama) which appears to have enjoyed particular freedoms under the authority of headman (Gramika).[49][46]

Apart from the various divisions and sub-divisions of the kingdom, there was a concept of urban settlement. The fifth-century Birur copper plate inscription of king Vishnuvarma describes Banavasi as "the ornament of Karnata desa, adorned with eighteen mandapikas" (toll collection centers) indicating it was a major trade center at that time. Numerous inscriptions make reference to the rulers at Banavasi as "excellent lords of the city" (puravaresvara). Excavations have revealed that Banavasi was a settlement even during the Satavahana period. By the fifth century, it was a fortified settlement and the Kadamba capital (Kataka). A later inscriptions of c. 692 of the Chalukyas refer to Banavasi and its corporate body (Nagara) as a witness to the granting of a village to a Brahmin by the monarch. A reference to the mercantile class (Setti) further indicates the commercial importance of Banavasi.[50]

One sixth of land produce was collected as tax. Other taxes mentioned in inscriptions were the levy on land (Perjunka), social security tax paid to the royal family (Vaddaravula), sales tax (Bilkoda), land tax (Kirukula), betel tax (Pannaya) and professional taxes on traders such as oilmen, barbers and carpenters.[49][46] Inscriptions mention many more taxes such as internal taxes (Kara and anthakara), tax on eleemosynary holdings (panaga), presents to kings (Utkota) and cash payments (Hiranya). The capital Banavasi had eighteen custom houses (mandapika) that levied taxes on incoming goods.[51] In recognition of military or protective service provided by deceased warriors, the state made social service grants (Kalnad or Balgacu) that supported their family. In addition to erecting a hero stone which usually included an inscription extolling the virtues of the hero, the grant would be in the form of land. Such land grant could be as small as a plot, as large as several villages, or even a large geographical unit depending on the heroes status.[52]

Economy

350 CE

Inscriptions and literature are the main source of information about the economy and the factors that influenced it. According to Adiga, from studies conducted by historians and epigraphists such as Krishna, Kalburgi, Kittel, Rice, B.R. Gopal and Settar, it is clear the kingdom depended on revenues from both agricultural and pastoral elements.[54] Numerous inscriptions, mainly from the modern Shimoga, Bijapur, Belgaum, Dharwad and Uttara Kannada regions (the ancient divisions of Belvola-300, Puligere-300, Banavasi-12,000) mention cattle raids, cowherds and shepherds. The numerous hero stones to those who fought in cattle raids was an indication of not only lawlessness but also of the importance of herding. The mention of the terms gosai (female goyiti), gosasa, gosasi and gosahasra in the adjective, the imposition of taxes on milk and milk products, the existence of large cattle herds and the gifting of a thousand cows as a mark of the donors affluence (gosahasram pradarum) indicate cow herding was an important part of the economy.[54] There are records that mention the shepherd settlements (kuripatti), cowherd settlements (turpatti) and numerous references to small hamlets (palli).[55]

Mixed farming, a combination of grazing and cultivation, mostly controlled by the wealthy Gavunda peasantry (today's Gowdas), seems to be the thing to do, for both the quantum of grain produced and number of cattle head determined opulence. There are several records that mention the donation of both gracing and cultivable land in units of kolagas or khandugas to either those who fought cattle thieves or to their families. A nomadic way of life is not prevalent in most communities, with the exception of hill tribes called Bedas. A semi-nomadic community, according to Durrett, they frequently depended on cattle thieving from outlying farms and the abduction of women. The Bedas subsisted by selling to merchants stolen cattle and such produce from the forest as meat, sandalwood and timber, and crops from disorganized agriculture.[56]

From inscriptions three types of land are evident; wet or cultivable land (nansey, bede, gadde or nir mannu) usually used to cultivate paddy (called akki gadde,akki galdege or bhatta mannu) or a tall stout grain yielding grass called sejje; dry land (punsey, rarely mentioned) and garden land (totta). A sixth-century grant refers to garden land that grew sugarcane (iksu). Other crops that were also cultivated were barley (yava), areca nut (kramuka), fallow millet (joladakey), wheat (godhuma), pulses (radaka), flowers were mostly for temple use and such lands called pundota, fruits such as plantains (kadali) and coconuts are also mentioned.[57]

Village (palli) descriptions in lithic and copper plate records, such as the Hiresakuna 6th-century copper plates from Soraba, included its natural (or man made) bounding landmarks, layout of agricultural fields, repairs to existing and newly constructed water tanks, irrigation channels and streams, soil type and the crops grown.[58] Repairs to tanks and construction of new ones was a preoccupation of elite, from kings to the Mahajanas, who claimed partial land ownership or a percentage of produce irrigated from the tank or both. Taxes were levied on newly irrigated lands, an indication the rulers actively encourage the conversion of dry land to cultivable wet land.[59] An important distinction is made between types of landholdings: Brahmadeya (individual) and non-Brahmadeya (collective) and this is seen in inscriptions as early as the third-fourth century in South India. Records such as the Shikaripura Taluk inscription indicate occasionally women were village headmen and counselors, and held land (gavundi).[60]

Functioning purely on the excess produce of the rural hinterland were the urban centers, the cities and towns (mahanagara, pura, and Polal) that often find mention in Kannada classics such as Vaddaradhane (c. 900) and Pampa Bharata (c. 940). References to townships with specialized classes of people such as the diamond and cloth merchants and their shops, merchant guilds (corporate bodies), important temples of worship and religious hubs, palaces of the royalty, vassals and merchants (setti), fortifications, courtesan streets, and grain merchants and their markets are a clear indication that these urban entities were the centers of administrative, religious and economic activity.[61]

Culture

Religion

The end of the Satavahana rule in the third century coincided with the advent of two religious phenomena in the Deccan and South India: the spread of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. This was a direct result of the Gupta dynasties ardent patronage to Hinduism in northern India and their aversion to other religions.[62] According to Sastri, till about the fifth century, South India witnessed a harmonious growth of these religions and the sects related to them without hindrance.

Appeasement of local deities and local practices which included offerings of sacrifices often went alongside popular Vedic gods such as Muruga, Shiva, Vishnu and Krishna.[63] However, from the seventh century onward, the growing popularity of Jainism and Buddhism became a cause for concern to the Hindu saints who saw the growth of these new faiths as heretic to mainstream Hinduism. This new found Hindu resurgence, especially in Tamil country, was characterized by public debates and enthusiastic rebuttals by itinerant saints. Their main purpose was to energize and revive Hindu Bhakti among the masses and bring back followers of sects considered primitive, such as the Kalamukhas, Kapalikas and Pasupatas, into mainstream Hinduism.[64][65]

The Kadambas were followers of Hinduism as evidenced by their inscriptions. The situation was the same with their immediate neighbors, the Gangas and the Pallavas. According to Adiga, their patronage to Brahmins well versed in the Vedas is all too evident. Inscriptions narrate various land grants to Brahmins that specify their lineage (gotra) as well as Vedic specialization.[66] According to Sircar, the early rulers called themselves Brahmanya or Parama-brahmanya, an indication of their propensity toward Vaishnavism (a branch of Hinduism).[67] The founding king Mayurasharma was, according to the Talagunda inscription, a Brahmin by birth though his successors may have assumed the surnameVarma to indicate their change to Kshatriya (warrior) status. An inscription of Vishnuvarma describes him as the "protector of the excellent Brahmana faith". His father Krishnavarma-I performed the Vedic ashvamedha ("Horse sacrifice"). There are numerous records that record grants made to Brahmins. According to Sircar, some fifth and sixth century inscriptions have an invocation of Hari-Hara-Hiranyagarbha and Hara-Narayana Brahman (Hari and Hara are another name of the Hindu gods Vishnu and Shiva).[68][69][70]

The Talagunda inscription starts with an invocation of the Hindu god Shiva while the Halmidi and Banavasi inscriptions start with an invocation of the god Vishnu. Madhukeshvara (a form of Shiva) was their family deity and numerous donations were made to the notable Madhukeshvara temple in Banavasi. Inscriptions mention various Shaiva sects (worshipers of the god Shiva) such as Goravas, Kapalikas, Pasupatas and Kalamukhas. Famous residential schools of learning existed in Balligavi and Talagunda. Vedic education was imparted in places of learning called Agrahara and Ghatika. However, they were tolerant to other faiths. The Kadamba kings appear to have encouraged Jainism as well. Some records of King Mrigeshavarma indicate describe donations to Jain temples and that King Ravivarma held a Jain scholar in high esteem. Names of such noted Jain preceptors as Pujyapada, Niravadya Pandita and Kumaradatta find mention in their inscriptions. Jainas occupied commanding posts of importance in their armies.[68][70] According to Adiga, image worship, which was originally prohibited, was now popularized among the common man and the monks. This helped raise funds for the construction of Jain temples (Chaitya). Installation of images of Jain monks (Jaina) in temples and a steady move toward ritualistic worship among the laymen undermined the concept of "quest for salvation" and the ascetic vigor of the religion.[71]

Grants were made to Buddhist centers as well. According to Kamath, the royal capital Banavasi had long been a place of Buddhist learning. In the seventh century, the Chinese embassy Xuanzang described Banavasi as a place of one hundred Sangharamas where ten thousand scholars of both the Mahayana and Hinayana Buddhism lived.[70][68] However, according to Ray, while there is evidence to prove that certain pre-Kadamba royal families, such as the Mauryas and Chutus may have patronized Buddhism, there is not much to say regarding the ruling Kadamba family, vast majority of whose inscriptions are Brahminical grants. In fact, according to Ray, the traces of Buddhist stupa sites that have been discovered in Banavasi are located outside the town.[72]

Society

The caste system was prevalent in the organized Hindu society with the Brahmins and the Kshatriyas at the top. This had a deep impact on such socially important events as marriage. Even Jainism and Buddhism which initially found popularity by avoiding social hierarchy began to develop the trappings of a caste-based society. This particular feature was, according to Singh, a unique feature of Jainism in what is modern-day Karnataka during the early medieval period. Both the sects of Jainism, the Digambara and the Svetambara followed a strict qualification process for persons worthy of initiation. Jinasena's classic Adipurana counts purity of ancestry, physical health and soundness of mind as the main attributes that made a person worthy of such initiation. Both Jinasena and Ravisena (author of Padmapurana) discuss the existence of a varna (distinction or caste) based society and the responsibilities of each varna.[73]

Majumdar notes that the Buddhist and Jain literature of the period accounts for the four varna by placing the Kshatriya above the Brahmin. While the Brahminical literature points to a tradition that permitted a Brahmin man to marry a woman of Kshatriya caste, a Brahmin woman was not allowed to marry a non-Brahmin man. Just the contrary seems to be the case with Buddhist and Jain literature which deema the marriage of a Brahmin man to Kshatriya woman as unacceptable but that of a Kshatriya man to a Brahmin woman as acceptable. Thus a caste system was in play with all the three main religions of the times.[74] However, Majumdar does point out the highly assimilate nature of the Hindu society where all the early invaders into India, such as the Kushans, the Greeks, the Sakas and the Parthians were all absorbed into the Hindu society without a trace of their earlier practices.[75]

A unique feature of medieval Indian society was the commemoration of the deceased hero by the erection of memorial stones ("hero stone"). These stones, the inscriptions and relief sculptures on them were meant to deify the fallen hero. According to Upendra Singh, The largest concentration of such stones, numbering about 2650 and dated to between the fifth and thirteenth centuries, are found in the modern Karnataka region of India. While most were dedicated to men, a few interesting ones are dedicated to women and pets. The Siddhenahalli, the Kembalu and the Shikaripura hero stones extol the qualities of women who died fighting cattle rustlers or enemies. The Gollarahatti and the Atakur inscription are in memory of a dog that died fighting wild boar, and the Tambur inscription of a Kadamba king of the Goa branch describes his death from sorrow of losing his pet parrot to a cat,[76] and the Kuppatur stone was in memory of a bonded servant who was given the honorific "slayer of the enemy" (ripu-mari) for bravely fighting and killing a man-eater Tiger with his club before succumbing to his injuries.[77]

According to Altekar, the practice of sati appears to have been adopted well after the Vedic period, because there was no sanction for the practice in the funeral hymns of the Rig Veda. According to him, even in the Atharva Veda, there is only a passing reference of widow being required to lie by the side of her husband's corpse on the funeral pyre, then alight from it before it was lit, for the chanting of hymns to commence that blessed her with future wealth and children. This was an indication that window remarriage was in vogue.[78] Altekar points out that even the authors of the Dharmasutras (400 BCE – c. 100)and the Smritis (c. 100 – c. 300), such as Manu and Yagnavalkya, do not make any mention of any ritual resembling sati in their description of the duties of women and widows in society, but rather prescribed the path of worldly renunciation as worthy.[79] It is from about c. 400 that the practice of sati begins to appear in the literature of Vatsyayana, Bhasa (Dutagatotkacha and Urubhanga), Kalidasa (Kumarasambhava) and Shudraka (Mirchchhakatika), with a real case in c. 510 when deceased general Goparaja's wife immolated herself on her husband's pyre. Then around 606, the mother of King Harshavardhana decided to predecease her terminally ill husband.[80]

This however did not find immediate support with noted poets such as Bana (c. 625) and other tantra writers who considered sati inhuman and immoral.[81] However around c. 700, the tide began to turn in northern India, especially in Kashmir, but found a later stronghold in Rajasthan. The belief in sati began to appeal, especially to the warrior classes, and the theory that performing sati cleansed the deceased husband of earthly sins and assured the couple a place in heaven caught on.[82] Occasionally concubines, mothers, sisters, sisters-in-law and even ministers, servants and nurses joined in the act.[82] This took its time to reach the Deccan (Kadamba territory) and the deep south (Tamil country) where the earliest cases, voluntary as they were, are seen by about c. 1000.[83] What was once a Kshatriya only practice came to be adopted by the Brahmins and even some Jains from around c. 1000.[84] In the modern Karnataka region (Kadamba territory), there are only eleven cases between c. 1000 – c. 1400 and forty-one cases between c. 1400 – c. 1600, mostly in the warrior communities indicating an overall lack of appeal.[85]

Physical education was very popular with men. The book Agnipurana encouraged men to avoid calisthenics with either partially digested food in their body or on a full stomach. Bathing with cold water after exercises was considered unhealthy. Medieval sculptures depict youth in physical combat training, doing gymnastics such as lifting the weight of the body with both hands, and doing muscular exercises such as bending a crowbar.[86] The terms malla and jatti occur often in literature indicating wrestling was a popular sport with the royalty and the commoners. Wrestlers of both genders existed, the woman fighters meant purely for the entertainment to a male audience. Several kings had titles such as ahavamalla ("warrior-wrestler"), tribhuvanamalla ("wrestler of the three worlds"). The book Akhyanakamanikosa refers to two types of combative sports, the mushtiyuddha ("fist-fight") and mallayuddha (or mallakalaga, "wrestling fight"). Wrestlers were distinguished based on their body weight, age, skill, proficiency and stamina. Those who exemplified themselves were recognized and maintained on specific diets.[87]

Much of the information we get about activities such as archery and hunting is from classics such as the Agni Purana (post 7th century) and others. The Agni Purana says "one who has made the vision of both of his mental and physical eyes steady can conquer even the god of death".[88] An archers proficiency, which depended as much on his footwork as on his fingers and keen eyesight, was proven if he could hit bullseye by just looking down at the target's reflection (Chhaya-Lakshya in Adipurana of c. 941, or Matsya-vedha in Manasollasa of c. 1129). Additional information is available in medieval sculptures which depict various archery scenes including one where a lady is taking aim from a chariot.[89] Hunting was a favorite pass time of royalty in forest preserves. It served as entertainment, physical exercise and a test of endurance (mrigiyavinoda and mrigiyavilasa). The medieval sculptors spared no effort in depicting hunting scenes. The Manasollasa describes twenty one types of hunt including ambushing deer at waterholes with the hunting party dressed in green and concealed in the hollows of trees. It mentions a special breed of hunting dogs chosen from places such as the modern Jalandhar, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Vidarbha which were preferred for their stamina in chasing and cornering the prey. According to the Vikramankadevacharita queens and courtesans accompanied the king on horseback.[90]

Architecture

According to Kamath, the Kadambas are the originators of the Karnataka architecture. According to Moraes their architectural style had a few things in common with the Pallava style. Kamath points out that their Vimana style (sanctum with its superstructure) is a Kadamba invention. A good example of this construction is seen in the Shankaradeva temple at Kadarolli in the modern Belgaum district. The structures themselves were simplistic with a square garbhagriha (sanctum) with an attached larger hall called mantapa. The superstructure (Shikhara) over the sanctum is pyramidal with horizontal non-decorative stepped stages tipped at the a pinnacle with a Kalasha (or Stupika).[92][93]

The beginnings of Kadamba architecture can be traced to the fourth century based on evidence in the Talagunda pillar inscription of c. 450. The inscription makes mention of a Mahadeva temple of the Sthanagundur Agrahara which Adiga identifies with the protected monument, the Praneshvara temple at Talagunda. The Praneshvara temple bares inscriptions of Queen Prabhavati (of King Mrigeshavarma) from the late fifth century and of their son King Ravivarma. From these inscriptions, Adiga concludes the temple existed in the late fourth century. Further, according to Adiga, the pillar inscription supports the claim that the earliest structure existed there as early as the third century and was under the patronage of the Chutu Satakarnis of Banavasi.[91]

Most of their extant constructions are seen in Halasi and surrounding areas with the oldest one ascribed to King Mrigeshavarma. Other notable temples in Halasi include the Hattikesavara temple with perforated screens by the doors, the Kallesvara temple with octagonal pillars, the Bhuvaraha Narasimha temple and the Ramesvara temple which shows a Sukhanasa projection (small tower) over the vestibule (Ardhamantapa) that connects the sanctum to the hall. All temples at Halasi have pillars with decorative capitals. The Kadamba style of tower was popular several centuries later and are seen in the Lakshmi Devi Temple at Doddagaddavalli (built by the Hoysalas in the 12th century) and the Hemakuta group of temples in Hampi built in the 14th century.[94][95][93] In addition to temples, according to the art historian K.V. Soudara Rajan, the Kadambas created three rock-cut Vedic cave temples cut out of laterite at Arvalem in Goa. Like their temples, the caves too have an Ardhamantapa ("half mantapa") with plain pillars and a sanctum which contain images of Surya (the sun god), Shiva and Skanda.[94][93]

In later centuries, Kadamba architecture was influenced by the ornate architectural style of their overlords, the Kalyani Chalukyas (Later Chalukyas). The best representations of this style are seen in the Mahadeva temple at Tambdi Surla in modern Goa built with an open mantapa in the late 12th-13th century by the Kadambas of Goa;[96] the single shrined (ekakuta) Tarakeshvara temple (modeled after the Mahadeva Temple, Itagi) built prior to c. 1180 with an open mantapa (and an ornate domical ceiling), a closed mantapa, a linked gateway and a Nandi mantapa (hall with the sculpture of the Nandi the bull);[97] the Madhukeshwara temple at Banavasi which shows several Later Chalukyas style additions over a pre-existing Early Chalukya surroundings;[98] and the 12th century, three shrined (Trikutachala) Kadambeshvara temple with open and closed mantapa at Rattihalli.[99]

_in_the_Tarakeshwara_temple_at_Hangal.JPG.webp) Tarakeshwara temple at Hangal, built by the Kadambas of Hangal

Tarakeshwara temple at Hangal, built by the Kadambas of Hangal Madhukeshwara temple at Banavasi, built by the later Kadambas of Banavasi

Madhukeshwara temple at Banavasi, built by the later Kadambas of Banavasi The Mahadeva temple at Tambdi Surla, Goa, built by the Kadambas of Goa

The Mahadeva temple at Tambdi Surla, Goa, built by the Kadambas of Goa

Language

According to the epigraphist D. C. Sircar, inscriptions have played a vital role in the re-construction of history of literature in India as well as the political history of the kingdoms during the early centuries of the first millennium. Some inscriptions mention names of noted contemporary and earlier poets (Aihole inscription of Ravikirti which mentions the Sanskrit poets Kalidasa and Bharavi). The development of versification and the Kavya style ("epic") of poetry appears first in inscriptions before making their appearance in literature. Further some Kavya poets were the authors of inscriptions too (Trivikramabhatta composed the Bagumra copper plates and the Sanskrit classic Nalachampu).[100] In the early centuries of the first millennium, inscriptions in the Deccan were predominantly in the Prakrit language. Then came a slow change with records appearing in bilingual Sanskrit-Prakrit languages around the middle of the fourth century, where the genealogy information is in Sanskrit while the functional portion was in Prakrit.[101] From around the fifth century, Prakrit fell out of use entirely and was replaced by the Dravidian languages. In the Kannada speaking regions in particular, the trend was to inscribe in Sanskrit entirely or in Sanskrit-Kannada.[102]

The credit of the development of Kannada as a language of inscriptions between the fourth and sixth centuries goes to the Kadambas, the Gangas and the Badami Chalukyas. Among the early ones are the Halmidi stone inscription and the Tagare copper plates which are ascribed to the Kadambas. While the main content of the inscriptions were in Sanskrit, the boundary specifications of the land grant were in Kannada. In subsequent two centuries, not only do inscriptions become more numerous and longer in size, these inscriptions show a significant increase in the usage of Kannada, though the invocatory, the implicatory and the panegyric verses are in Sanskrit.[103] Settar points out that there are inscriptions where the implicatory verses have been translated verbatim into Kannada also. In fact Kannada composed in verse meters start making their appearance in inscriptions even before being committed to literature.[104]

Inscriptions in Sanskrit and Kannada are the main sources of the Kadamba history. The Talagunda, Gudnapur, Birur, Shimoga, Muttur, Hebbatta, Chandravalli, Halasi and Halmidi inscription are some of the important inscriptions that throw light on this ancient ruling family of Karnataka.[9] Inscriptions of the Kadambas in Sanskrit and Kannada ascribed to Kadamba branches have been published by epigraphists Sircar, Desai, Gai and Rao of the Archaeological Survey of India.[105] The Kadambas minted coins, some of which have Kannada legends which provide additional numismatic evidence of their history.[106] The Kadambas (along with their contemporary Ganga dynasty of Talakad) were the first rulers to use Kannada as an additional official administrative language, as evidenced by the Halmidi inscription of c. 450. The historian Kamath claims Kannada was the common language of the region during this time. While most of their inscriptions are in Sanskrit, three important Kannada inscriptions from the rule of the early Kadambas of Banavasi have been discovered.[107][108][109]

Recent reports claim that the discovery of a 5th-century Kadamba copper coin in Banavasi with Kannada script inscription Srimanaragi indicating that a mint may have existed in Banavsi that produced coins with Kannada legends at that time. The discovery of the Talagunda Lion balustrade inscription at the Praneshvara temple during excavations in 2013, and its publication by the ASI in 2016, has shed more light on the politics of language during the early Kadamba era. The bilingual inscription dated to 370 CE written in Sanskrit and Kannada is now thought to be the oldest inscription in the Kannada language.[111]

In modern times

Kadambotsava ("The festival of Kadamba") is a festival that is celebrated every year by the Government of Karnataka in honor of this kingdom.[112] The creation of the first native Kannada kingdom is celebrated by a popular Kannada film, Mayura starring Raj Kumar. It is based on a popular novel written in 1933 with the same name by Devudu Narasimha Sastri.[113] On 31 May 2005 Defence minister of India Pranab Mukherjee commissioned India's most advanced and first dedicated military naval base named INS Kadamba in Karwar.[114]

The Indian state government of Goa owned bus service is named after the Kadambas Dynasty and is known as Kadamba Transport Corporation (KTCL).The royal lion emblem of the Kadambas is used a logo on its buses. The lion emblem logo became an integral part of KTCL since its inception in 1980 when the corporation was set up to provide better public transport service.[115]

See also

Notes

- Ram Bhushan Prasad Singh. Jainism in Early Medieval Karnataka C. A.D. 500-1200. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 25.

- Vidya Dhar Mahajan. Ancient India. S. Chand. p. 438.

- Arthikaje, Mangalore. "History of Karnataka-The Shatavahanas-10, section:Origin of the Kadambas". 1998-00 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- Majumdar (1986), p.237

- Mann (2011), p. 227

- Chaurasia (2002), p.252

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 161

- R.N. Nandi in Adiga (2006), p. 93

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), pp. 30-39

- Sastri (1955), p.99

- T. Desikachari (1991). South Indian Coins. Asian Educational Services. pp. 39–40.

- Rao, Seshagiri in Amaresh Datta (1988), p. 1717

- Minahan (2012), p. 124

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), p.30

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), pp. 30–31

- Sen (1999), p. 468

- Moraes, George M. (1990). The Kadamba Kula: A History of Ancient and Mediaeval Karnataka. Asian Educational Services. pp. 15–17, 30–49, 322–323. ISBN 978-81-206-0595-4.

- Ramesh, K.V. (1984), p. 6

- Sastri (1955), pp. 99–100

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), pp.26, 161–162

- Ramesh, K.V. (1984), p. 3

- Majumdar (1986), pp. 235–237

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), p.31.

- Arthikaje, Mangalore. "History of Karnataka-The Shatavahanas-10, section:Mayuravarma". 1998-00 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), p. 32

- Sastri (1955), p. 100

- Majumdar (1986), p. 239

- Sastri (1955), p. 101

- Majumdar (1986), p.240

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), p. 33

- Sen (1999), p. 244

- Majumdar (1986), p.239

- Majumdar (1986), pp. 241–242

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), pp. 34, 53

- Majumdar (1986), p.243

- Visaria, Anish. "Search, Seek, and Discover Jain Literature". JaineLibrary-jainqq.org. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- Gokhale, Shobhana (1973). "Researches in Epigraphy". Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute. 33 (1/4): 77–100. ISSN 0045-9801. JSTOR 42936410.

- Sircar, Dinesh Chandra (1987). Epigraphia Indica Vol.33. THE DIRECTOR GENERAL, archaeological survey of INDIA. pp. 86–90.

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), p. 34

- Majumdar (1986), p.245

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), p. 35

- Majumdar (1986), p. 246

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), p.38

- Dikshit (2008), pp. 74–75

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), p.35

- Arthikaje, Mangalore. "History of Karnataka-The Shatavahanas-10, section:Administration". 1998-00 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- Adiga (2006), p. 168

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), pp. 35–36

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), p. 35)

- Adiga (2006), pp. 74, 85

- Adiga (2006), p. 216

- Adiga (2006), p. 177

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 25, 145. ISBN 0226742210.

- Adiga (2006), pp. 55–67

- Adiga (2006), pp. 36–87

- Adiga (2006), pp. 65–67

- Adiga (2008), pp. 47–55

- Adiga (2006), pp. 21–22

- Adiga (2006), p. 45

- Singh, Upendra (2008), p. 593

- Adiga (2006), pp. 71–86

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian ((2003), p.188

- Sastri (1955), pp. 381–382

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 189

- Sastri (1955), p. 382

- Adiga (2006), pp.280-281

- Sircar (1971), p.54

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), pp. 36–37

- Sircar (1971), p.53

- Arthikaje, Mangalore. "History of Karnataka-The Shatavahanas-10, section: Education and Religion". 1998-00 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- Adiga 92006), pp. 249–252

- Ray (2019), Chapter-Introduction, Section-Perception: Buddhist Banavasi, Past and Present

- Singh, R.B.P. (2008), pp. 72–73

- Majumdar (1977), pp. 201–202

- Majumdar (1977), pp. 202–203

- Singh, Upendra, (2008), p. 48

- Kamat, J.K. (1980), p. 79

- Altekar (1956), pp. 117–118

- Altekar (1956), p.119

- Altekar (1956), p. 123

- Altekar (1956), pp. 124–125

- Altekar (1956), p. 127

- Altekar (1956), p. 128

- Altekar (1956), pp. 128–129

- Altekar (1956), pp. 130–131

- Kamat, J.K. (1980), p. 68

- Kamat, J.K. (1980), p. 69

- Kamat, J.K. (1980), p.74

- Kamat, J.K. (1980), p. 75

- Kamat, J.K. (1980), pp. 75–77

- Adiga (2006), p.287

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), pp37-38

- Kapur (2010), p. 540

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), p. 38

- Chugh (2017), chapter 2.1, section: Vishnu

- Hardy (1995), p.347

- Hardy (1995), p.330

- Hardy (1995), p. 323

- Hardy (1995), p. 342

- Satyanath T.S. in Knauth & Dasgupta (2018), p.123

- Saloman (1998), pp.90-92

- Saloman (1998), p. 92

- Satyanath T.S. in Knauth & Dasgupta (2018), pp.125-126

- Satyanath T.S. in Knauth & Dasgupta (2018), p. 125

- Dr. D.C. Sircar, Dr. P.B.Desai, Dr. G.S. Gai, N. Lakshminarayana Rao. "Indian Inscriptions-South Indian Inscriptions, vol 15,18". What Is India News Service, Friday, 28 April 2006. Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kamath, S.U. (1980), p. 12

- A report on Halmidi inscription, Muralidhara Khajane (3 November 2003). "Halmidi village finally on the road to recognition". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 24 November 2003. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- Ramesh, K.V. (1984), p.10

- Kamath, S.U. (1980), p. 37

- "Kannada inscription at Talagunda may replace Halmidi as oldest". Deccan Herald. 12 January 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Kadambotsava is held at Banavasi as it is here that the Kadamba kings organized the spring festival every year. Staff Correspondent (20 January 2006). "Kadambotsava in Banavasi from today". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- Das (2005), p.647

- Defense Minister Pranab Mukherjee opened the first phase of India's giant western naval base INS Kadamba in Karwar, Karnataka state, on 31 May. "India Opens Major Naval Base at Karwar". Defence Industry Daily. 21 May 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "Kadamba dynasty logo to be reinstaed on Goa govt buses". The Economic times.

References

Book

- Adiga, Malini (2006) [2006]. The Making of Southern Karnataka: Society, Polity and Culture in the early medieval period, AD 400–1030. Chennai: Orient Longman. ISBN 81-250-2912-5.

- Altekar, Ananth Sadashiv (1956) [1956]. The Position of Women in Hindu Civilization, from Prehistoric Times to the Present Day. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0325-6.

- Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian, Nilakanta K.A. (2003) [2003]. History of South India (Ancient, Medieval and Modern), Part 1. New Delhi: Chand Publications. ISBN 81-219-0153-7.

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002) [2002]. History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers. ISBN 978-81-269-00275.

- Chugh, Lalit (2017) [2017]. Karnataka's Rich Heritage – Temple Sculptures & Dancing Apsaras: An Amalgam of Hindu Mythology, Natyasastra and Silpasastra. Chennai: Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-947137-36-3.

- Das, Sisir Kumar (2005) [2005]. History of Indian Literature: 1911-1956, struggle for freedom : triumph and tragedy. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-7201-798-7.

- Dikshit, Durga Prasad (1980) [1980]. Political History of the Chālukyas of Badami. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications.

- Hardy, Adam (1995) [1995]. Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation-The Karnata Dravida Tradition 7th to 13th Centuries. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-312-4.

- Kamath, Suryanath U. (2001) [1980]. A Concise history of Karnataka from pre-historic times to the present. Bangalore: Jupiter Books. OCLC 7796041.

- Kamat, Jyothsna K. (1980) [1980]. Social Life in Medieval Karnataka. Bangalore: Abhinav Publications. OCLC 7173416.

- Kapur, Kamalesh (2010) [2010]. Portraits of a Nation: History of Ancient India: History. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers. ISBN 978-81-207-52122.

- Ramesh, K.V. (1984) [1984]. Chalukyas of Vatapi. Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan. OCLC 13869730.

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1977) [1977]. Ancient India. New Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass Publications. ISBN 81-208-0436-8.

- Majumdar & Altekar, Ramesh Chandra & Ananth Sadashiv (1986) [1986]. Vakataka - Gupta Age Circa 200-550 A.D. New Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass Publications. ISBN 81-208-0026-5.

- Mann, Richard (2011) [2011]. The Rise of Mahāsena: The Transformation of Skanda-Kārttikeya in North India from the Kuṣāṇa to Gupta Empires. Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-21754 6.

- Minahan, James B. (2012) [2012]. Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia, section:Kannadigas. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-659-1.

- Rao, Seshagiri L.S. (1988) [1988]. Amaresh Datta (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Indian literature vol. 2. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-260-1194-7.

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha, ed. (2019) [2019]. Decolonising Heritage in South Asia: The Global, the National and the Transnationa. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-50559-9.

- Sastri, Nilakanta K.A. (2002) [1955]. A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. New Delhi: Indian Branch, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-560686-8.

- Saloman, Richard (1998) [1998]. Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509984-2.

- Satyanath, T.S. (2018) [2018]. K. Alfons Knauth, Subha Chakraborty Dasgupta (ed.). Figures of Transcontinental Multilingualism. Zurich: LIT Verlag GambH & Co. ISBN 978-3-643-90953-4.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999) [1999]. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age Publishers. ISBN 81-224-1198-3.

- Singh, R.B.P (2008) [2008]. Jainism in Early Medieval Karnataka. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass. ISBN 978-81-208-3323-4.

- Singh, Upinder (2008) [2008]. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India:From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. India: Pearsons Education. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- Sircar, Dineshchandra (1971) [1971]. Studies in the Religious Life of Ancient and Medieval India. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass. ISBN 978-8120827905.

Web

- "History of Karnataka – The Shatavahanas-10, Arthikaje". OurKarnataka.Com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- "Indian Inscriptions". Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- "5th century copper coin discovered at Banavasi". Deccan Herald. 7 February 2006. Archived from the original on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- "Halmidi village finally on the road to recognition". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 3 November 2003. Archived from the original on 24 November 2003. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- "Indian Coins, Dynasties of South India, Govindayara Prabhu". G.S Prabhu. 1 November 2001. Archived from the original on 6 January 2004. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Karnataka |

|---|

|