Imperial Army (Holy Roman Empire)

Imperial Army (Latin: Exercitus Imperatoris,[1] German: Kaiserliche Armee) or Imperial Troops (Kaiserliche Truppen or Kaiserliche) was a name used for several centuries, especially to describe soldiers recruited for the Holy Roman Emperor during the early modern period. The Imperial Army of the Emperor should not be confused with the Army of the Holy Roman Empire (Exercitus Imperii (Romani), Reichsarmee, Armée du Saint-Empire), which could only be deployed with the consent of the Imperial Diet. The Imperialists effectively became a standing army of troops under the Habsburg Emperors from the House of Austria, which is why they were also increasingly described in the 18th century as "Austrians", although its troops were recruited not just from the Archduchy of Austria but from all over the Holy Roman Empire.

The Empire and the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy supplied almost all the Holy Roman Emperors during the Early Modern Period. Their title of Emperor was one that was bound not so much to a territory, but to a person.

Accordingly, the Imperial Army was a force established by the Emperor, with privileges in the whole of the Holy Roman Empire. The Emperor was not permitted to raise troops in the electoral states, but had inter alia the right to recruit soldiers in the imperial cities and in all other territories.

Independent of the Emperor's ability to raise his own army, the Imperial Diet could establish the Army of the Holy Roman Empire, the "troops of the empire" in the event of a Reichskrieg.

Bavarian period and "Austrianisation"

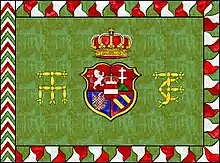

During the Imperial interregnum of 1740-1742, Habsburg troops no longer formed the army for the Emperor, but that of the Queen of Hungary. During the War of the Austrian Succession, Queen Maria Theresa and the Austrian House of Habsburg, fought for their survival within the European system of power. She initially lost her battle for the Imperial crown for her husband, Francis Stephen of Lorraine. With the acquisition of the crown by Charles VII of the Bavarian House of Wittelsbach, units from the Electorate of Bavaria formed the Imperial Army for a short time, from 1742 to 1745. A year after the loss of the imperial crown, the Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary directed her troops to wear green instead of gold for officers' sashes and for the regimental flags. Gold has always been considered an imperial attribute.

After the 1745 imperial election of Maria Theresa's husband, Francis I, the Habsburg troops were given back their Imperial status. Although Maria Theresa took the title of empress, she put no value on her coronation as empress. This was reflected in the title of her army, which was now called "Roman Imperial-Royal" (römisch kaiserlich-königlich). The colloquial, shorter term, "Austrian", established itself during the Seven Years' War (1756-1763) and subsequent conflicts in the War of Bavarian Succession (1778/1779), the Russo-Austrian war against the Turks (1787-1792) and the Napoleonic Wars.[3]

Prussian and Protestant journalists increasingly lost interest in a universal Reich concept, which, for a long time, had earned the imperial troops their special position. Even Maria Theresa's son, Emperor Joseph II, with his centralizing reforms that promoted an Austrian territorial state, encouraged Imperial politics less and less. In 1804, the Austrian imperial crown was created. Only two years later, Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor dissolved the increasingly defunct Holy Roman Empire.

Operations of the Habsburg Imperial Army

During the Early Modern Period, the Imperial Army fought in all the wars affecting the Empire, usually allied with the Army of the Holy Roman Empire and other territorial forces.

- Long Turkish War (1593–1606)

- Thirty Years' War (1618–1648)

- Second Northern War (1655–1660)

- Austro-Turkish War (1663–1664)

- Scanian War (1674–1679)

- Nine Years' War (1688–1697)

- Great Turkish War (1683–1699)

- War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714)

- Austro-Turkish War (1714–1718)

- War of the Polish Succession (1732–1738)

- Austro-Russian–Turkish War (1736–1739)

Growth of the Habsburg Imperial Army

The Thirty Years' War led to an unusually strong arming of the Emperor. In 1635, the Imperial Army reached a peak of 65 regiments of foot, with a nominal strength of 3,000 men each. During the course of the war, 532 regiments were formed and disbanded. In 1648 only 9 regiments of foot, 9 regiments of horse and a regiment of dragoons remained. The Army's paper strength in 1625 was 61,900 (16,600 cavalry), rising to 111,100 in 1626 (25,000 cavalry), 112,700 in 1627 (29,600 cavalry), 130,200 in 1628 (27,300 cavalry), 128,900 in 1629 (17,900 cavalry), and 150,900 in 1630 (21,000 cavalry). Due to disease and desertion, the amount of effectives available at any given time often deviated from paper strength; depending on the year, anywhere from 60 to 85 percent of paper strength was actually usable. By the end of the war, the Imperial Army's effective strength had been reduced to 42,300. The Imperial Army figures do not include soldiers on the side of the Emperor who marched to war under their own princes; for example, at the end of the war, the 42,300 soldiers of the Imperial Army were supported by 35,500 soldiers from the Westphalian and Bavarian circles.[4]

Gradually, a standing imperial army evolved as a result of the many wars. Of the 49 regiments raised for the Second Northern War, 23 remained in 1660. The 1760s saw 28 new regiments being formed, and the following decade saw a further 27.

The annual average strengths of the Emperor's military forces throughout mid 17th to early 18th century are as follows:[5]

- Austro-Turkish War, 1662–1664: 82,700 (51,000 Kaiserliche Armee, 31,700 Reichsarmee)

- Franco-Dutch War, 1672–1679: 132,350 (65,840 Kaiserliche Armee, 66,510 Reichsarmee)

- Great Turkish War, 1683–1689: 88,100 (70,000 Kaiserliche Armee, 18,100 Reichsarmee)

- Nine Years War, 1688–1697: 127,410 (70,000 Kaiserliche Armee, 57,410 Reichsarmee)

- War of the Spanish Succession, 1701–1714: 260,090 (126,000 Kaiserliche Armee, 134,090 Reichsarmee)

The Habsburgs were infrequently successful at convincing the rest of the Empire to shoulder the burden of the army. Their greatest success in this respect was during the War of the Spanish Succession. Total expenditure was 650 million florins across 1701–14, including the cost of the official contingents and additional auxiliaries provided by the imperial states, as well as their other directly incurred war expenditures. About 90 million of this (14% of the total) was covered by subsidies from the Empire’s British and Dutch allies. The remainder was divided roughly one-third for the Habsburgs (187 million, 29% of the total) and two-thirds for the remaining imperial estates (373 million, 57% of the total). The Empire’s overall effort exceeded Britain’s military and naval expenditure by 237 million florins.[6]

Units and formation

See also

- Kaiserlich (concept explanation)

- Army of the Holy Roman Empire

References

- N. Iorga, Studii şi documente cu privire la istoria Romînilor, Bucarest, Stabilimentul grafic I. V. Socecǔ, 1901, p. 261 : "Omnes annales et historiae, tam huius provinciae, quam externarum gentium testantur quod ab anno 1774 usque ad annum 1789 continuis incendiis, tiraniis, irruptionibus vexata fuit haec provincia ; quare intravit exercitus imperatoris Romani et bellum gessit cum Turcis hic in provincia usque ad annum 1793. Sequenti anno statim incepit revolutio cum Pascha vidinensi et terribilis pestis, in tantum quod etiam filii patriae debuerint aufugere, et haec omnia mala durarunt usque ad annum 1802.

- "Austrian infantry Ordinair-Fahne of the 1743 pattern". Kronoskaf. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- c.f. Johann Christoph Allmayer-Beck: Das Heer unter dem Doppeladler. Habsburgs Armeen 1718–1848. 1981, pp. 48f. and War Archive (ed.): Österreichischer Erbfolgekrieg, 1740–1748. Vol. 1. 1896, p. 384.

- Wilson, Peter H. (2009). "Europe's Tragedy: A History of the Thirty Years War." Tables 3 and 6.

- Peter Wilson. "Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire." Cambridge: 2016. pp. 460–461, Table 13.

- Peter Wilson. "Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire." Cambridge: 2016. p. 454.

Sources

- War Archive (ed.): Österreichischer Erbfolgekrieg, 1740–1748. Nach den Feld-Acten und anderen authentischen Quellen bearbeitet in der kriegsgeschichtlichen Abteilung des K. und K. Kriegs-Archivs. Vol. 1. Seidel, Vienna, 1896.

- Heeresgeschichtliches Museum Wien (ed.): Von Söldnerheeren zu UN-Truppen. Heerwesen und Kriege in Österreich und Polen vom 17. bis zum 20. Jahrhundert (= Acta Austro-Polonica. Bd. 3). Heeresgeschichtliches Museum, Vienna, 2011, ISBN 978-3-902551-22-1.

- Johann Christoph Allmayer-Beck, Erich Lessing: Die kaiserlichen Kriegsvölker. Von Maximilian I. bis Prinz Eugen. 1479–1718. Bertelsmann, Munich, 1978, ISBN 3-570-00290-X.

- Johann Christoph Allmayer-Beck: Das Heer unter dem Doppeladler. Habsburgs Armeen 1718–1848. Bertelsmann, Munich, 1981, ISBN 3-570-04414-9.

- Peter Rauscher, ed. (2010), Kriegführung und Staatsfinanzen. Die Habsburgermonarchie und das Heilige Römische Reich vom Dreißigjährigen Krieg bis zum Ende des habsburgischen Kaisertums 1740 (in German), vol. 10, Münster: Aschendorff, ISBN 978-3-402-13993-6.

- Gerhard Papke (1983), "I. Von der Miliz zum Stehenden Heer: Wehrwesen im Absolutismus", in Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (ed.), Deutsche Militärgeschichte in sechs Bänden (in German), vol. 1, Herrsching: Manfred Pawlak Verlagsgesellschaft, ISBN 3-88199-112-3, Lizenzausgabe der Ausgabe Bernard & Grafe Verlag, Munich

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Jürg Zimmermann (1983), "III. Militärverwaltung und Heeresaufbringung in Österreich bis 1806", in Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (ed.), Deutsche Militärgeschichte in sechs Bänden (in German), vol. 1, Herrsching: Manfred Pawlak Verlagsgesellschaft, ISBN 3-88199-112-3, Lizenzausgabe der Ausgabe Bernard & Grafe Verlag, Munich

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)