Kaman HH-43 Huskie

The Kaman HH-43 Huskie is a helicopter developed and produced by the American rotorcraft manufacturer Kaman Aircraft. It is perhaps most distinctive for its use of twin intermeshing rotors, having been largely designed by the German aeronautical engineer Anton Flettner.

| HH-43 Huskie | |

|---|---|

| |

| HH-43B Huskie of the United States Air Force | |

| Role | Firefighting/rescue |

| Manufacturer | Kaman Aircraft |

| First flight | 21 April 1953 |

| Retired | Early 1970s |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | United States Air Force United States Marine Corps United States Navy |

| Number built | 193 |

First flown on 21 April 1953, the HH-43 went into production and was operated by several military air services, including the United States Air Force, the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps. It was primarily intended for use in aircraft firefighting and rescue in the close vicinity of air bases, but was extensively deployed during the Vietnam War. It was used as a search and rescue platform, having often been enhanced with makeshift modification and new apparatus to better suit the tropical conditions. Under the aircraft designation system used by the U.S. Navy pre-1962, Navy and U.S. Marine Corps versions were originally designated as the HTK, HOK or HUK, for their use as training, observation or utility aircraft, respectively. In American service, it was retired during the 1970s, having been rendered obsolete by the arrival of larger, more capable rotorcraft.

Development

In 1947, the German aeronautical engineer Anton Flettner was brought to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip.[1] He was the developer of the two earlier synchropter designs from Germany during the Second World War: the Flettner Fl 265 which pioneered the synchropter layout, and the slightly later Flettner Fl 282 Kolibri ("Hummingbird"), intended for eventual production. Both designs used the principle of counter-rotating side-by-side intermeshing rotors, as the means to solve the problem of torque compensation, normally countered in single–rotor helicopters by a tail rotor, fenestron, NOTAR, or vented blower exhaust. Flettner remained in the United States and became the chief designer of the Kaman company.[2] In this capacity, he designed numerous new helicopters that used the Flettner double rotor.

On 21 April 1953, the first prototype, referred to by the manufacturer as the K-225, made its maiden flight. It was later adopted by the United States Navy as the HTK-1, by which point it was outfitted with a single Lycoming O-435-4 flat-six piston engine, producing 240 hp (180 kW). During 1954, for an experiment jointly conducted by Kaman and the U.S. Navy, a single HTK-1 was modified and flown with its piston engine having been replaced by a pair of turbine engines, becoming the world's first twin-turbine helicopter in the process.[3]

Subsequently, a much more powerful Pratt & Whitney R-1340 Wasp radial piston engine, capable of producing 600 hp (450 kW), powered for the far heavier HOK-1, HUK-1, and H-43A versions for the United States Marines, U.S. Navy, and the United States Air Force, respectively. The U.S. Air Force also opted to procure two models that were powered by a single turboshaft engine: the HH-43B and HH-43F.[4] The HH-43B variant established several world records for helicopters in its class during the early 1960s, including for rate of climb, altitude, and distance traveled.[5]

Design

The HH-43 had an unusual intermeshing contra-rotating twin-rotor arrangement. Flight control was primarily effected by a series of servo-flaps, or large tabs, that was located on the trailing edge of each rotor blade; the actuation of these flaps would cause the rotors to warp and thus cause the helicopter to either rise or descend as desired.[5] The rotor blades were composed of laminated wood; these restricted the aircraft's use in heavy rains as it could cause blade delamination.[6] There was no conventional tail rotor, its absence gave the rotorcraft a somewhat unusual look.[7] The contra-rotating twin rotors posed a particular hazard on the ground; crews were instructed to avoid approaching or departing the vehicle from the sides, but to instead advance or leave the vehicle from the front, as the blades would be at their highest at this position.[8]

The interior of the HH-43 was divided in two somewhat cramped compartments, the cockpit at the front and an aft crew compartment, which were connected by a small opening that was too narrow for most personnel to pass through.[9] Dependent on the mission being performed, the aft compartment would be used to house firefighters, medics, mechanics, and/or rescued personnel; folding sidewall-mounted seats were provided for up to four personnel in this space, while the cockpit normally housed the pilot and co-pilot alone. In a typical configuration, a pair of clamshell doors would be fitted that could open up into the aft area of the rear compartment; in tropical conditions, these doors would often be removed to help cool the interior; in such a configuration, an aft net would be installed to prevent any personnel from falling out of the aircraft. No weapons mounts were officially approved, but some improvised arrangements did see the use of a Browning Automatic Rifle at the aft ramp position.[10]

On the exterior of the rotorcraft, a motorised hoist that was typically used for rescue missions was commonly fitted; control of the hoist was normally exercised from within the aft compartment, but the pilot could also directly control the hoist via the cyclic stick. For rescues at sea, a padded sling, nicknamed the 'horse collar', was fitted to the end of the hoist to aid in retrieval operations.[9] Due to unsatisfactory performance in the field, other devices were usually fitted, including the wire basket "Stokes litter" and a heavy "forest penetrator".[11]

Operational history

The HH-43 Huskie was procured by the U.S. Air Force; the first H-43As were delivered to the service in November 1958 while the first H-43Bs were accepted in June 1959.[5] The U.S. Air Force primarily procured the type to perform local base rescue operations and to fight aircraft fires. For the latter capacity, the H-43 was commonly outfitted with an airborne fire suppression kit that hung beneath it; this kit, which was developed at Wright-Patterson AFB, weighed only 1,000 pounds yet could output almost 700 gallons of fire-fighting foam. Huskies were usually capable of reaching crash sites before ground vehicles could, saving often-critical time in the rescue.[5] During 1962, the USAF opted to change the H-43 designation to HH-43 to reflect the rotorcraft's role as a rescue vehicle. The HH-43F was the first model delivered to the U.S. Air Force, these differed from earlier models primarily by engine modifications that produced greater lift.[5]

The Huskie was deployed overseas during the Vietnam War; several detachments of the Pacific Air Rescue Center, the 33d, 36th, 37th, and 38th Air Rescue Squadrons, and the 40th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron operated the type. Personnel came to commonly refer to the aircraft by its call sign "Pedro". Early on, the rotorcraft's limited range proved to be a hindrance to operations; some crews resorted to an improvised additional fuel tank housed within the aft compartment, increasing fuel capacity by roughly 75 percent.[12] During the conflict, the HH-43 flew more rescue missions than all other rotorcraft combined, largely due to its unique hovering capability; between 1966 and 1970, the type performed a total of 888 combat rescue, comprising 343 aircrew rescues and 545 non-aircrew rescues.[5] The type was also occasionally used as a firefighting vehicle in the theatre as well.[13] Noting the shortcomings of the HH-43, the procurement of newer aircraft, such as the Sikorsky SH-3 Sea King, was accelerated; their arrival in quantity supplanted the type and saw its being entirely replaced during the early 1970s.[14][15]

Variants

- K-240

- company designation from HTK-1/TH-43E

- K-600

- proposed civilian counterpart of HOK-1[16]

- K-600-3

- civilian counterpart of H-43B[16]

- K-600-4

- company designation of HOK-3 development[16]

- K-600-5

- HH-43F[17]

- XHTK-1

- two two-seat aircraft for evaluation

- HTK-1

- three-seat production version powered by a 240 hp (180 kW) Lycoming O-435-4 flat-six piston engine for the United States Navy,[18][19] later became TH-43E, 29 built

- XHTK-1G

- one example for evaluation by the United States Coast Guard

- HTK-1K

- one example for static tests as a drone

- XHOK-1

- prototype of United States Marine Corps version, two built

- HOK-1

- United States Marine Corps version powered by a 600 hp (450 kW) R-1340-48 Wasp radial piston engine; later became OH-43D, 81 built

- HOK-3

- proposed development powered by a Blackburn-Turbomeca Twin Turmo 600 turboshaft powerplant.[16]

- HUK-1

- United States Navy version of the HOK-1 with R-1340-52 radial piston engine; later became UH-43C, 24 built

- H-43A

- USAF version of the HOK-1; later became the HH-43A, 18 built

- HH-43A

- post-1962 designation of the H-43A

- H-43B

- H-43A powered by an 860 shp (640 kW) Lycoming T53-L-1B turboshaft engine, three-seats and full rescue equipment; later became HH-43B, 200-built

- HH-43B

- post-1962 designation of the H-43B

- UH-43C

- post-1962 designation of the HUK-1

- OH-43D

- post-1962 designation of the HOK-1

- TH-43E

- post-1962 designation of the HTK-1

- HH-43F

- HH-43B powered by an 825 shp (615 kW) Lycoming T53-L-11A turboshaft engine with reduced diameter rotors, 42 built and conversions from HH-43B

- QH-43G

- One OH-43D converted to drone configuration

Operators

_(14755998095).jpg.webp)

Surviving aircraft

In addition to those on static display and the airworthy example at the Olympic Flight Museum, many H-43s are still in use with private owners.

- Burma

- UB6166 – HH-43B is on display at the Defence Services Museum in Naypyidaw, Mandalay.[30]

- Germany

- 62-4547 – HH-43F on static display at the Hubschraubermuseum Bückeburg in Bückeburg, Lower Saxony.[31][32]

- Pakistan

- 62-4556 – HH-43P on static display at the Pakistan Air Force Museum in Karachi, Sindh.[33]

- Thailand

- H5-2/05 – Type 5 on static display at the Royal Thai Air Force Museum in Bangkok.[34][35]

- United Kingdom

- 62-4535 – HH-43B under restoration at the Midland Air Museum in Baginton, Warwickshire. This airframe is one of only two examples on display in the United Kingdom.[32][36]

- United States

- Composite – HH-43F on static display at the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks, Connecticut. This airframe is painted as 60-0289, but was built up from parts of various HH-43s.[32][37]

- 129313 – HTK-1/TH-43E on static display at the Tillamook Air Museum in Tillamook, Oregon.[38] This airframe is painted in Navy markings.[39]

.jpg.webp)

- 129801 – HOK-1/OH-43S in storage at the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks, Connecticut.[32]

- 138101 – HOK-1/OH-43D in storage at the United States Army Aviation Museum at Fort Rucker near Daleville, Alabama. BuNo 138101 was formerly displayed indoors at the National Naval Aviation Museum at NAS Pensacola, Florida (circa 1986–2001) in a dark blue finish with USMC markings. It was repainted from its original USMC markings to pre-Vietnam U.S. Army colors when it was loaned to the Army by the National Naval Aviation Museum.[32]

- 139974 – OH-43D on static display at the Pima Air & Space Museum, adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB in Tucson, Arizona. This airframe is painted in USMC markings.[40]

- 139982 – HOK-1/OH-43D in storage at the Carolinas Aviation Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina. This airframe is painted in Marine Corps markings.[32][41]

- 139990 – HOK-1/OH-43D in storage at the Flying Leatherneck Aviation Museum at MCAS Miramar in San Diego, California. This airframe is painted in USMC markings.[42][43] It was previously on display at MCAS Tustin in Tustin, California; but was moved to MCAS Miramar after MCAS Tustin was closed and NAS Miramar was transferred from control of the Navy to the Marine Corps.[32]

- 58-1837 – HH-43A in storage at the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks, Connecticut.[32]

- 58-1841 – HH-43F on static display at the Military Firefighter Heritage Display at Goodfellow Air Force Base in San Angelo, Texas. It is incorrectly painted with Air Force Serial Number 58-1481. This Huskie was a ground trainer (circa 1962–1976) at Sheppard Air Force Base, so it retained the square-tail empennage that was removed from almost all other Huskies after repeated rotor strikes in heavy winds. After being sold by the military, but before arriving at its current location, it was on display at the Pate Museum of Transportation in Cresson, Texas.[44]

- 58-1853 – HH-43F on static display at the Museum of Aviation at Robins Air Force Base in Warner Robins, Georgia.[45]

- 59-1578 – HH-43F on static display at Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, New Mexico.[46] This may be the same airframe listed on other sites as being located at the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History, which has since moved off-base, but adjacent to, Kirtland Air Force Base.

- 60-0263 – HH-43B on static display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio.[47]

- 62-4513 – HH-43F on static display at the Castle Air Museum at the former Castle AFB in Atwater, California.[48][49]

- 62-4531 – HH-43F on static display at the Pima Air & Space Museum adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB in Tucson, Arizona.[50]

- 62-4532 – HH-43B on static display at the Air Mobility Command Museum at Dover AFB in Dover, Delaware.[51]

- 62-4561 – HH-43B on static display at the Hill Aerospace Museum at Hill AFB in Roy, Utah.[52]

- 64-17558 – HH-43F airworthy at the Olympic Flight Museum in Olympia, Washington. This airframe is painted in USAF markings.[53][54][55]

Specifications (HH-43F / K-600-5)

Data from Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1965-66,[17] National Museum of the United States Air Force : Kaman HH-43B Huskie[5]

General characteristics

- Crew: Two flight crew and two rescue crew

- Capacity: 3,970 lb (1,801 kg) maximum payload

- Length: 25 ft 2 in (7.67 m) fuselage

- Height: 15 ft 6.5 in (4.737 m) to tip of highest blade

- 12 ft 7 in (4 m) to top of rotor pylons

- Empty weight: 4,620 lb (2,096 kg)

- Gross weight: 6,500 lb (2,948 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 9,150 lb (4,150 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 350 US gal (291 imp gal; 1,325 L)

- Powerplant: 1 × Lycoming T53-L-11A turboshaft engine, 825 shp (615 kW) (de-rated from 1,150 shp (858 kW))

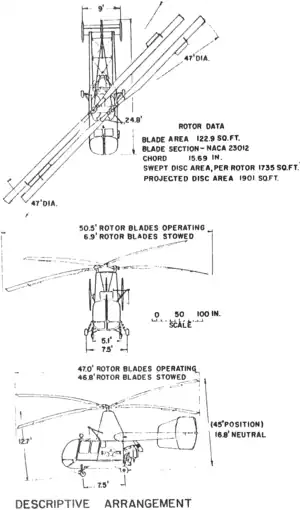

- Main rotor diameter: 2 × 47 ft 0 in (14.33 m)

- Main rotor area: 3,470.34 sq ft (322.405 m2)

- Blade section: - root: NACA 23012; tip: NACA 23011[56]

Performance

- Maximum speed: 120 mph (190 km/h, 100 kn)

- Cruise speed: 110 mph (180 km/h, 96 kn)

- Range: 504 mi (811 km, 438 nmi) at 5,000 ft (1,524 m) and 8,270 lb (3,751 kg) TOW

- Service ceiling: 23,000 ft (7,000 m)

- Hover ceiling IGE: 20,000 ft (6,096 m)

- Hover ceiling OGE: 16,000 ft (4,877 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,800 ft/min (9.1 m/s)

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

Citations

- Boyne, Walter J. (2011). How the Helicopter Changed Modern Warfare. Pelican Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-58980-700-6.

- ""Anton Flettner"; Hubschraubermuseum Bückeburg". Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "Twin Turborotor Helicopter". Popular Mechanics. Vol. 102, no. 2. August 1954. p. 139. ISSN 0032-4558.

- LaPointe 2001, p. 74.

- "Kaman HH-43B Huskie". National Museum of the United States Air Force™. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- LaPointe 2001, pp. 69, 73.

- LaPointe 2001, p. 69.

- Prouty, Ray (2009). Helicopter Aerodynamics Volume I. Eagle Eye Solutions. p. 487. ISBN 978-0557089918.

- LaPointe 2001, p. 70.

- LaPointe 2001, pp. 69-70, 72.

- LaPointe 2001, pp. 71-72.

- LaPointe 2001, pp. 75-76.

- LaPointe 2001, p. 110.

- Hobson, Chris (2001). Vietnam Air Losses. Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing. p. 258. ISBN 1-85780-115-6.

- LaPointe 2001, p. 77.

- Bridgman, Leonard, ed. (1958). Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1958-59. London, UK: Jane's All the World's Aircraft Publishing Co. Ltd. pp. 320–321.

- Taylor, John W.R., ed. (1965). Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1965-66. London, UK: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, Ltd. pp. 249–250.

- AN 01-260HAA-1 Pilot's Handbook: Navy Model HTK-1 Helicopters. U.S. Navy. 1 September 1952. p. 1. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- "Kaman HTK-1 (Helicopter)". Tillamook Air Museum. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- "World Helicopter Market". Flight International. Iliffe. 11 July 1968. p. 49. Archived from the original on 2015-06-23. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- "World Helicopter Market". Flight International. Iliffe. 11 July 1968. p. 50. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- "IIAF History". Copyright © 1999-2012 IIAF.net. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "Iran Air Force HH-43F Huskie". Demand media. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "Military Helicopter Market 1971". Flight International. Iliffe. p. 579. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- "Decommissioned Aircraft PAKISTAN AIR FORCE". Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "ROYAL (Archives) THAI AIR FORCE" (PDF). RTAF.af. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "Kaman HH-43B Huskie (K-600)". Demand media. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "Kaman HOK-1 (OH-43D) Huskie US MARINES". H43-huskie.com. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "Kaman HUK-1 (UH-43C) Huskie US NAVY". H43-huskie.com. Archived from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "Preservation Notes - Myanmar". Air-Britain News. Air-Britain: 380. March 2014.

- "Kaman HH-43F HUSKIE". Das Hubschraubermuseum Buckeburg. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- Ragay, Johan (25 August 2016). "PRESERVED Kaman H-43 Huskie". Ragay.nl. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Aerial Viuals - Airframe Dossier - Kaman H-43, s/n 62-4556 PakAF, c/n 182". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Building 5:Helicopters and last propeller fighter". Royal Thai Air Force Museum. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- "Airframe Dossier - Kaman HH-43B Huskie, s/n H5-2/05 RTAF, c/n 115". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Aircraft Listing". Midland Air Museum. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Kaman HH-43F 'Huskie'". New England Air Museum. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Aircraft". Tillamook Air Museum. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Airframe Dossier - KamanH-43, s/n 129313 USN". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "HUSKIE [139974]". Pima Air & Space Museum. Pimaair.org. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "139982". Flickr. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Aircraft Listing" (PDF). Flying Leathernecks. Flying Leatherneck Historical Foundation. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- "Airframe Dossier - Kaman OH-43D Huskie, s/n 139990 USN, c/r N5190Q". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- Mock, Stephen P. (July 2005). "Pedro's Big Move". Pedro News. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "HH-43F "HUSKIE"". Museum of Aviation. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Airframe Dossier - Kaman HH-43F Huskie, s/n 59-1578 USAF". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Kaman HH-43B Huskie". National Museum of the US Air Force. 18 May 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "OUR COLLECTION". Castle Air Museum. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Airframe Dossier - Kaman HH-43F Huskie, s/n 62-4513 USAF, c/n 139". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "HUSKIE [62-4531]". Pima Air & Space Museum. Pimaair.org. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "HH-43B Huskie". Air Mobility Command Museum. AMC Museum Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "HH-43B "Huskie"". Hill Air Force Base. 19 October 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "HH-43 Huskie". Olympic Flight Museum. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Airframe Dossier - KamanH-43, s/n 64-17558 USAF, c/r N4069R". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "FAA REGISTRY [N4069R]". Federal Aviation Administration. U.S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

- Chiles, James R. (2007). The God Machine: From Boomerangs to Black Hawks: The Story of the Helicopter. New York, US: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-80447-8.

- Francillon, René J. (1997). McDonnell Douglas Aircraft since 1920: Volume II. London, UK: Putnam. ISBN 0-85177-827-5.

- Frawley, Gerard (2003). The International Directory of Civil Aircraft, 2003-2004. Fyshwick, Canberra, Act, Australia: Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd. p. 155. ISBN 1-875671-58-7.

- LaPointe, Robert L. (2001). PJs in Vietnam: The Story of Airrescue in Vietnam as Seen Through the Eyes of Pararescuemen. Northern PJ Press. ISBN 0-9708-6710-7.

- Munson, Kenneth (1968). Helicopters and other Rotorcraft since 1907. London, UK: Blandford Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7137-0493-8.

- Thicknesse, P. (2000). Military Rotorcraft: Brassey's World Military Technology series. London, UK: Brassey's. ISBN 1-85753-325-9.

- Wragg, David W. (1983). Helicopters at War: A Pictorial History. London, UK: R. Hale. ISBN 0-7090-0858-9.