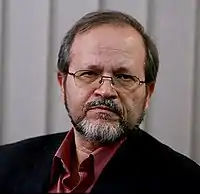

Kambiz Roshanravan

Kambiz Roshanravan (Persian: کامبیز روشنروان, born 9 June 1949) is an Iranian performing musician, composer, conductor and music teacher. As one of the famous composers in Iranian classical and traditional music, he has composed or arranged various works in these styles using well-known Western and Iranian forms such as: symphony, sonata, symphonic poem, concerto, row music forms and local music. His professional life is divided into three parts: composing, teaching and professional activity in the music community. During his career he has created many works for film music, vocal music, symphony orchestra and chamber, and for many years he has tried to teach, write books, pamphlets and articles in the field of education, He is referred to as an expert musician in theoretical and harmonious discourses.

Kambiz Roshanravan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | Kambiz Roshanravan |

| Born | 9 June 1949 Tehran, Iran |

| Origin | Iran |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, conductor, musician |

| Instrument(s) | Flute, piano, santour, tombak |

| Years active | 1966–present |

Biography

Family

Kambiz Roshanrovan was born on June 9, 1949, in Tehran,[1][2] Kashanchi Alley, in front of the "Municipal Cafe" (the location of the student park and theater of the current city), in religious families with moderate financial situation. His father was from Bushehr and a person with strong religious beliefs, so that he held congregational prayers with his children at home and in addition to himself reciting the Qur'an in a vocal tone, he also encouraged his children to do so. Her mother was from Mashhad and had a higher education. She had a great interest in art, literature and painting, which is why she was one of the first women to receive a bachelor's degree in literature from the university in those years.[3]

Childhood

Kambiz's childhood was marked by a lot of mischief and playfulness,[4] so that when he entered primary school at Manouchehri Elementary School at the age of six, there was not a day that he was not punished by the School Principal.[3] The first signs of his interest in music appeared during this period. The "Municipal Cafe" was located near his residence, which made him choose to play and have fun during the summer holidays. In this café, although there were all kinds of play equipment, but more attention was drawn to the night tent show that was performed in another part of the café, and unlike his other playmates, he just sat and watched these performances. The reason for his intense interest in marquee was the presence of a Kamancheh player who performed the soundtrack of this play with a pleasant voice, and he enjoyed the soundtrack more than any other part of the play. He also spent the night in the same café watching movies, still paying close attention to the soundtrack. Most of his lessons, except math, were low-grade, and most of the time, when he returned home, his clothes were torn and his mother had to sew them to be ready for school the next day.[3]

Adolescence

Studying at the Higher Conservatory of Music

Roshanravan's great interest in music, even in families where neither of them was interested in music, made him eager to listen to the songs and tunes that were played on the radio at that time and to imitate the songs. After each song you hear, he would go to the backyard and sing the song aloud accurately and completely, which would surprise and encourage the neighbors of the child's talent in singing. Ironically, in this neighborhood, there was a person named Mostafa Kasravi who was the composer and conductor of the Radio Orchestra. Hearing these songs, he decided to talk to the Roshanravan's father and encourage him to send his son to the music conservatory. The father initially objected, but eventually, at Kasravi's urging, agreed to enroll his son in the conservatory, provided he only played the violin. Roshanravan later found out that the main reason for his father's condition was that he had once been interested in music and wanted to learn the violin, but had failed due to the family's religious prejudices, So he was looking for the realization of his long-held dream in his son..[5]

After completing his primary education, Kasravi introduced him to the Higher Conservatory of Music for registration. After a musical talent test and entrance exams, he was welcomed and admired by the conservatory officials and was accepted as a talented student. But his entry into the conservatory was the beginning of the story, because at that time the selection for the music student was examined and selected according to the criteria of music teachers, based on physical physique, fingers, lips, etc., and they were the ones who decided what instrument the student could play to succeed in the field. These criteria led from the very beginning to oppose the choice of a violin instrument for Roshanravan, It was believed that his fingers were not suitable for playing this instrument and he could not become a good musician in this field. Finally, a small instrument called Piccolo was found to be suitable for his fingers, and he was required to learn it. He, who had no interest or knowledge of this instrument, could not fulfill his father's wishes at the very beginning.[5]

About a year had passed since Kambiz Roshanarvan attended the conservatory, but during this time he had not made significant progress in learning Piccolo, Because he continued to play and have fun, and this behavior caused problems, Because his instrument was stuck in his pocket due to its small size and lack of a protective box, and this caused the instrument to be damaged or its keys to break, he had to go to the conservatory repair shop again and again to fix the instrument's technical defect. Eventually, he decided to move his studies from the Higher Conservatory of Music (classical music education) to the National Conservatory of Music (traditional music education) so that he could learn the violin there.[5]

Studied at the National Conservatory of Music

Kambiz Roshanvarvan had to go through the entrance and talent test again at the National Conservatory of Music. He was accepted this time as well, but there, too, he was opposed to choosing a violin and the flute was considered suitable for him, but the problem was that there was no flute teacher and instrument in this conservatory and the instrument had to be bought from abroad. And the delivery of this order took six months. Inevitably, until the preparation of the instrument and the selection of the teacher, it was suggested by Hossein Dehlavi, who was in charge of the conservatory, that he receive the instrument and learn the Santur, thus making him the first student to learn two specialized Iranian and Western instruments at the same time. He studied the Santur first with Dariush Safvat and then with Arfa Atraei, and then with the flute in the presence of Manouchehr Monshizadeh (who was the first flutist of the Tehran Symphony Orchestra), the theory of music and solfege by Mostafa Kamal Poortorab and harmony, poetry and music learned from Hossein Dehlavi. During this period, Roshanravan became acquainted with both of its specialized instruments and was seriously committed to its training and development.[6] But again, he had a sudden problem at the end of the ninth year of school, and at the same time he suffered from several diseases, including tuberculosis, intestinal fever, lung disease, and the doctors' recommendation that he could not continue playing the instrument and studying in the conservatory. And if he recovers, he should continue his education in regular schools. Finally, after about 40 days of intensive care and complete quarantine, he was able to miraculously recover from this tragic accident and regain his health.[7]

After complete recovery, he returned to the conservatory and continued his progress in learning Persian music with dulcimer and Western music techniques with flute. In his tenth year, he was assigned to learn the piano; Because the piano was a mandatory instrument for all music students to teach harmony in the conservatory.[8] In the same year, Hossein Dehlavi invited Hossein Tehrani to teach Tombak at the conservatory and introduced four students, including Roshanvarvan, Ali Rahbari, Esmail Tehrani, and Esmail Vaseghi, to teach him. Hossein Tehrani trained them for a year, after which he left the task to his student, Mohammad Esmaili. After witnessing the success of his students for some time, Esmaili formed a group of five Tombak musicians under his leadership and held several concerts throughout the cities of Iran.[6] Thus, Roshan Ravan mastered four instruments and simultaneously with studying and trying to obtain a diploma, every week and every time, with one of these instruments, he performed programs live on the national television of Iran, whether in groups or alone. While teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts in his final year, he eventually graduated for the first time in the conservatory's history with two diplomas in Santur and Flute.[9]

studying in university

After graduating, Roshanrovan entered the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Tehran in 1967. There he chose composition as his main field and in the presence of masters such as Houshang Ostvar (Harmony), Mehdi Barkashli (phonetics), Mohammad Taghi Massoudieh (ethnomusicology) and Alireza Mashayekhi (Form and Analysis), he studied various fields of music, but specialized courses. But he took specialized courses with Thomas Christian David (composition and flute) and Emanuel Melik-Aslanian (piano). While attending university, he continued his educational activities and concerts, which began in his final years at the conservatory. In addition to teaching at the Academy of Arts, he performed in various cities with the Tombak Quartet Ensemble, which he had founded since his time at the Conservatory. He also became a member of the flute soloist in the Majlis Orchestra of the National Television of Iran and held several concerts. At the university, he collaborated with student music groups with various instruments in which he specialized, and the result was the performance of his own works and those of classical music composers. In addition, the same conservatory from which he had graduated immediately invited him to collaborate and teach, and thus, during his student days, while teaching at the conservatory and other educational centers, holding various concerts and learning to compose, he succeeded in his activities. He continued his music career and in 1351, he obtained a bachelor's degree.[10][11][12]

Military service

After graduating from the University of Tehran, he enlisted in the army, and these days, too, had many adventures for him. Roshanarvan completed his military training in Tabriz. During this time he was oblivious to military training, and with the notebooks he carried with him, he only practiced composing, which is why he received the lowest rank in the final exams of the training period.[13] This rank made it impossible for him to choose the city of his choice to serve. He was informed that only the quota of Sarpol-e-Zahab city remained. During his transfer and temporary stay in Kermanshah, he met by chance with the military music commander of the Kermanshah Division, whom they already knew and who was previously a musician with the Tehran Symphony Orchestra. He suggested to the Enlightenment that he be replaced in this position so that he could go abroad to continue his education. Roshanarvan accepted the offer. When military officials learned of his abilities, they welcomed him and, in addition to the Kermanshah army, appointed him commander-in-chief of the military music in the provinces of Kermanshah and Kurdistan.[14][15] After assuming responsibility, Kambiz Roshanvarvan expressed his dissatisfaction with the state of the military orchestras and decided to begin the professional training of soldiers by writing etudes and rehearsals for each instrument. He also traveled to various cities in the two provinces, expanding military training and organizing military orchestras. After a while, his success in improving military music led him to establish a music school in the city of Kermanshah and use the same soldiers he had trained as a teacher. The activities of this school attracted a large number of students from the surrounding cities, and some of these soldiers continued their professional activities in music after their service.[16] On the other hand, the directors of the Music Conservatory in Tehran, who were suffering from a severe shortage of music teachers, wrote a letter to Mehrdad Pahlbod, the then Minister of Culture and Arts, requesting the transfer of Roshanarvan to Tehran through legal procedures. The request was granted, but the Roshanarvan one, who had worked hard for the soldiers and orchestras, did not see the students' departure in their favor, Therefore, after receiving the transfer letter, which he had 48 hours to introduce himself to Tehran, he ignored it and did not leave. Two weeks after the date of the letter, he was arrested by Ajoudani and forcibly transferred to Tehran. Thus, he completed the rest of his military service by teaching in the conservatory.[14][17]

Studying in America

Roshanarvan immediately after his service, he based his determination on the fact that he must go to the United States to continue his education.[18] Earlier, his composition teacher (Thomas Christian David) at the University of Tehran had advised him to go to Austria with him and continued his studies at the Vienna Academy of Music. But Roshanarvan knew that the level of education at the Vienna School was in the 18th and 19th centuries, and because he wanted to study contemporary and twentieth-century music, he believed that American or French universities were a better place to learn the style.[19] He corresponded with various prestigious American universities for admission, and his application for a master's degree was accepted in all options. But he got into trouble again; Upon learning of this, conservatory officials secretly asked Mehrdad Pahlbod, the Minister of Culture and Arts, whose brother (Commander Minabashian) was the commander of the army's ground forces, not to issue an end-of-service card until an alternative teacher was found. Thus, Roshanvarvan lost the academic year, and when he became aware of the actions of the directors of the conservatory, he finally succeeded in obtaining a permit to leave the country by receiving a termination card, and after a six-month trip to London to learn English and return to Iran left the country for the United States to study at the University of Southern California (USC) a year late without informing the conservatory.[20][21]

He came to Iran to marry only once during his studies and returned to the United States with his wife. He also wrote his dissertation and conducted some student orchestras. He also taught at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Department of Persian Music for a time, teaching students Radif, Santur, and Tombak.[22][23][24]

Pahlavi era

Kambiz Roshanravan's professional activity during this period can be divided into three parts: playing, teaching and composing.[25] In addition to teaching, he continued to expand his activities by playing in concerts, collaborating with the National Television Orchestra of Iran, the Saba Orchestra led by Hossein Dehlavi, and other music groups.[26] He also started composing along with his other activities and performed some of his compositions in the same concerts. In 1974, at the request of the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, He released his first works in the form of an album with the names: Blue-eyed Boy, Atal Matal Tutuleh and Music based on the poems of Abu Sa'id Abu'l-Khayr.[27] In the same year, he entered the world of cinema by composing the first soundtrack for the short film Passenger, made by Abbas Kiarostami.[28] In 1975, he wrote, prepared, supervised, performed and published ten phonograph disc records of Radif's sung by Mohammad Reza Shajarian and famous traditional musicians of that time, based on the row of Musa Maroofi.[29][30][31] He also collaborated with other filmmakers in 1975 and 1976, including Nafiseh Riahi (Purple Pencil), Amir Naderi (elegy) and Khosrow Haritash (Kingdom), and was able to establish himself as a composer.[32]

After the revolution

At the time of the Islamic Revolution, Kambiz Roshanravan was studying in the United States. Influenced by the events in Iran, he decided to compose his dissertation with the name and theme of Bloody Friday (Lament for the Martyrs of September 8) in the style of avant-garde music.[33] He, who wanted to continue his doctoral studies and while his scholarship was cut, left the graduation ceremony and the ceremony of receiving the first prize for composing, returned to Iran with his wife in December 1979. He said: "Many university professors insisted that I not return to Iran. They said that music was not in a good condition in Iran at the moment due to the revolution. The family also said that I should not return to Iran. I preferred my country to everything, I could not stand it anymore and I wanted to return to my homeland as soon as possible."[34]

Immediately after arriving in Iran, he signed a teaching contract with the University of Tehran, but after a while he realized that music in all its aspects had been shut down and that the advice he had been given not to go to Iran was correct. In February of that year, he decided to perform the piece Bloody Friday. The performance of this work made it difficult for him due to the problems caused by the revolution. Eventually he managed to gather around him by inviting orchestral musicians and other musicians from other groups, when carrying instruments was also banned in public places. Eventually, this work was performed by the Tehran Symphony Orchestra at Vahdat Hall, with 240 musicians and singers, led by itself and performed for about fifteen nights.[35][36]

Cultural Revolution and War

In early 1980, the Cultural Revolution was taking shape. Roshan Ravan was teaching at the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Tehran at the time, and at the same time, he witnessed people attacking the university, destroying, beating, and breaking glass. Eventually the universities were closed and he became unemployed. He says about this: "... Because I had nothing to do, I would go around the university every day curiously to see what would happen and where the work would end up … What currents and events I did not witness… I witnessed the book burning festival…They broke the glass of bookstores…This was not something I returned to Iran for, and it was really impossible for me to believe it." Now all avenues for his work had come to a standstill; So, in consultation with his wife, they decided to leave Iran and go back to the United States to continue their education and teaching there, but the closure of the US embassy delayed obtaining a visa for three months. The visa was issued when the Iran-Iraq war broke out and all air borders were closed following the bombing of Mehrabad airport. Thus, he stayed in Tehran and his trip did not end.[37][38]

With the start of the war and the beginning of a new era in the life of Kambiz Roshanravan by staying in Iran, he wanted to improve and prosper music production in any way. In 1980, he first turned to film music and composed the first post-revolutionary soundtrack for Storm Wave and then Bloody Rice, for which he did not receive a salary. Then, about five months after the start of the war, with the help of his former friends and classmates: Mohammad Shams, Esmail Tehrani and Esmail Vaseghi, he produced a joint album on the Iran-Iraq war called Sacrifice Season with the voice of Siamak Aligholi, which was published by Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults.[39][40][41]

The peak period

At the beginning of the 1981s, universities were reopened and he joined the Radio and Television University in 1982. During this time, film production gradually flourished, and composers were able to work in film music. Roshanvarvan was one of the first composers in this genre after the revolution, and soon other people entered the field. In the sixties, he became known as one of the most prolific film music makers and left works such as: Ambassador, Chrysanthemums, Cold Roads, Amir Kabir, Shah Shekar and..[42][43]

Following his involvement in film music, Roshanravan entered into negotiations with cultural authorities to persuade them to grant him and other composers an album production license. Eventually, the officials of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance agreed to publish such works in a very limited way, but many obstacles were created and these obstacles extended to the radio and television. The use of rhythms such as six and eight and forms such as color, four beats and the making of any dance and joyful song were prohibited in these productions and the choice of poetry was also censored. However, despite many difficulties, he finally managed to release his first exclusive and orchestral album after the revolution, in 1983–84, under the name of Yadegare Doost with the voice of Shahram Nazeri.[44][45] In the following years, in addition to collaborating with Mohammad Reza Shajarian and Shahram Nazeri, he has composed or arranged songs for other singers such as: Alireza Eftekhari, Bijan Bijani, Mohammad Esfahani, Alireza Ghorbani and...[46][47]

With the passage of time and the establishment of educational centers, the production of albums, films and serials was added to the activities of Kambiz Roshanvarvan. In addition to composing for albums, stage music and cinema, he has been widely used in prestigious educational centers such as: music conservatories (girls and boys), academy of arts, faculty of fine arts, Islamic center of film education, faculty of radio and television, faculty of cinema, theater, university Tarbiat Modarres, University of Arts, Islamic Azad University and… has taught in the field of music and cinema. He has made continuous efforts in the field of education and composition, and has been praised many times during his artistic life and has won numerous awards from various domestic and foreign festivals.[48][49] Also in 2004, he was awarded a first-class degree in art by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. Because of his years of experience in teaching, writing books, publishing pamphlets, articles, and scientific lectures, he is referred to as an expert musician in theoretical and harmonious discourses.[50][51][52]

Responsibilities and union activities

Kambiz Roshanravan left the 1980s behind with a lot of work in the field of education and composition. At this time, in the early 1990s, he felt that the conservatories were not responding to the large number of new music applicants and students, and that new private schools needed to be established. He decided to enter into negotiations with the cultural authorities, and in this way he succeeded, and by attending the councils and accepting some responsibilities, such as membership in the Central Council for Supervision of Free Art Schools, the High Council of Art Conservatories, the High Council of Music (Ministry of Culture and Guidance Islamic), the Council for Planning and Supervision of Music Education of the Radio and Television of Iran, the Art Planning Committee of the Cultural Revolution Headquarters, accelerated this matter and in 1998, established a private school. He says that as a result of this work, as long as he was on the councils (2006), he led to the creation and licensing of a large number of music schools across the country.[53][54][55]

In 1993, with the establishment of the Cinema House, independent guild institutions were formed in various fields of cinema. He also took the initiative in this direction and with the help of some of his colleagues, he established an organization called the Iranian Cinema Composers Association and after that he concentrated his activity in the cinema house. After a while, in addition to being the president of the Composers' Association, he became a member of the board of directors of the Cinema House (1998–1999) and for a few years he was the managing director of the "Cinema Magazine" (1998–2002). After his success at the Cinema House and the gathering of famous film music composers in a guild, in 1999 he was invited by the Director General of Music of the Ministry of Guidance to establish a music house for other music disciplines with the help of his colleagues. He was a member of the founding board of the House of Music, and after its formation, he was elected as a member and chairman of the board. He gradually reduced his activity in the cinema house and increased his activity in the music house. For this reason, from 2001 to 2004, he was elected as the director of the "Teachers' Association" and from 2004 to 2006, he was elected as the director of the "Association of Composers and Orchestra Conductors". He also co-founded the House of Artists as a member of the founding board and board of directors, thus completing his collaboration and union activities in forming and establishing three artistic houses by writing various bylaws and statutes and accepting responsibilities.[56][57][58]

Kambiz Roshanvarvan's activities in the music community are not limited to guild work and he is present in many festivals and cultural centers as a member of the jury or expert, such as: Member of the jury of Fajr Music Festivals (1989–2000), Jury of Young Music Festivals (1991–2003), the jury of the Holy Defense Music Festivals (1991–2004), the chairman of the jury of the first music festival for the disabled (2000) and a member of the jury of the Cinema House Festival. He has also been the Vice-Chairman of the UNESCO-affiliated National Music Committee in Iran.[59][60] Finally, in 2006, when he was employed by the Radio and Television University, he retired, after which he resigned from most of his union and artistic responsibilities. He attributed this to the fatigue caused by years of constant activity, and said that he intends to rejuvenate the ideas and work left behind by composing and composing, as well as being with his family. An opportunity that had not been created for him in previous years.[61]

Private life

Kambiz Roshanravan is married to "Azar Afrooz". They have two daughters (Hiva and Hila) and two sons (Hooman and Ali).[62] He owes part of his success to his wife's support. In his personal life, he has been composing after midnight due to his intense daily activities in education, playing and recording music. For this reason, to stay awake, by drinking too much coffee and taking a cold shower, he contracted various diseases such as headache, high fever, sinusitis, and then diabetes, which is still ongoing. He points out that during his artistic activities, he has always suffered from insomnia, and with the treatment of doctors, he was able to sleep 3 hours a day, which has increased to 4 hours during his retirement.

However, he states that if he is born again, he will still choose music and says:[63]

"... I have sought with all my might the love that has been in my heart and soul since I was a child and has followed me to this day… It is a long, hard, ups and downs… I did not have the joys and pleasures of my youth… Excessive work and effort and not having a normal life have endangered my health, but in return for what I have gained, I am satisfied... If I put what I have lost in one cup and what I have gained in another cup, the role I have played in advancing Iranian music is much heavier…»

References

- تحریـریه (2021-09-08). "Kambiz Roshan Ravan". Artmag.ir. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "زندگینامه: کامبیز روشنروان (۱۳۲۸-)". همشهری آنلاین (in Persian). 2009-02-02. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". artebox.ir. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "کامبیز روشن روان؛ آهنگسازِ معلم". ایمنا (in Persian). 2020-06-08. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". artebox.ir. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". artebox.ir. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 33. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 41. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 43. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- TABNAK, تابناک |. "روایت کامبیز روشن روان از فراز و فرود کوشش موسیقاییاش". fa (in Persian). Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "کامبیز روشن روان". artebox.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". artebox.ir. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 49. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 50. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 50. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "هنرمند - کامبیز روشن روان - آرته باکس". artebox.ir. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". artebox.ir. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "روزنامه شرق: كامبيز روشنروان:درحال سقوطآزاد در موسيقي هستيم". www.pishkhan.com. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Nasiri Far, Habibollah (1991). Men of traditional and modern Iranian music. Tehran: Road Publications. p. 208.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 50. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 22. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 52. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Nasiri Far, Habibollah (1991). Men of traditional and modern music. Tehran: Road Publications. p. 209.

- Nettl, Bruno (1987). he Radif of Persian Classical Music: Studies of Structure and Cultural Context in the Classical Music of Iran. Elephant and Cat. p. 12.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 23. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "Kambiz Roshanravan". artebox.ir.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 61. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". artebox.ir. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- ""فصل ایثار"". پرتال کودک. 2016-12-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". artebox.ir. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "کامبیز روشنروان؛ آهنگساز مولف و نظریهپرداز موسیقی ملی – ایرنا". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "روش آموزشی کتاب «هارمونی جامع کاربردی» متفاوت است- اخبار فرهنگی تسنیم | Tasnim". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "شعر و موسیقی از عناصر اصلی ما ایرانیان است/ پریسا احدیان – مجله فرهنگی و هنری بخارا". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "كامبیز روشن روان". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Nasiri Far, Habibollah (1991). Men of traditional and modern Iranian music. Tehran: Rah Publications. p. 69.

- "روایت کامبیز روشن روان از فراز و فرود کوشش موسیقاییاش – تابناک | TABNAK". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 67–68–69. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "خانه موسیقی ایران – کامبیز روشن روان". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- "معرفی داوران فیلم های سینمایی جشن سینمای ایران – بانی فیلم". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.

- "هنرمند – کامبیز روشن روان – آرته باکس". 2021-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- Sanaei Fard, Reza (2015). Souvenir. Great Entrepreneurs Publications. p. 76–77–78. ISBN 978-600-6925-50-9.