Kampecaris

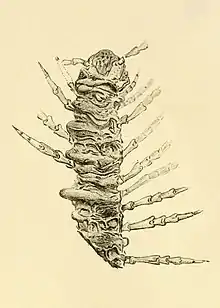

Kampecaris is an extinct genus comprising the Kampecarida, an enigmatic group of millipede-like arthropods, from the Silurian and early Devonian periods of Scotland and England.[1][2] They are among the oldest known land-dwelling animals.[3][4] They were small (20–30 millimetres (0.79–1.18 in) long), short-bodied animals with three recognizable sections: an oval head divided along the midline, ten limb-bearing segments forming a cylindrical trunk that tapered slightly towards the front, and a characteristic swollen tail formed by a modified segment that tapers at its rear into an "anal segment". The cuticle forming their exoskeletons was thick, heavily calcified, and composed of two layers.[5]

| Kampecaris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Kampecaris forfarensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Myriapoda |

| Class: | Diplopoda |

| Order: | incertae sedis |

| Genus: | †Kampecaris Page, 1856 |

| Type species | |

| †Kampecaris forfarensis Peach, 1882 | |

| Other species | |

| |

The genus was named by David Page in 1856 for a "small phyllopod, or the larval stage of some larger crustacean" from Silurian deposits of Angus, Scotland (formerly Forfarshire), but it was not until 1882 that B. N. Peach recognized the affinities of this animal to millipedes and named the species K. forfarensis. Peach named another Silurian species, K. obanensis, from Old Red Sandstone deposits from the Scottish island of Kerrera in 1899; John Almond questioned the affinity of this species to Kampecaris in 1985, for several reasons including the presence of 14 segments behind the head. In 1951, B. B. Clarke described a Devonian species, K. dinmorensis, from Dinmore Hill, Herefordshire, England. Another Devonian species, K. tuberculata,[5] was subsequently recognized as being closer to flat-backed millipedes in the group Archipolypoda, and renamed to Palaeodesmus.[6]

The taxonomic placement of Kampecarida is unresolved, and it has never been subject to phylogenetic analysis.[1] At least some of the body segments may have been diplosegments, and a legless collum may have been behind the head, which are millipede-like traits but not exclusive to millipedes.[2] Almond treated it an order of uncertain placement in an unpublished 1986 thesis, and in 1998 W. A. Shear considered it likely warranted class-level rank within the Myriapoda.[2] In a 2010 review of the myriapod fossil record, Shear and G. D. Edgecombe considered it likely represented an extinct high-level taxon within the Diplopoda (millipedes).[1]

References

- Shear, William A.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2010). "The geological record and phylogeny of the Myriapoda". Arthropod Structure & Development. 39 (2–3): 174–190. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2009.11.002.

- Shear, William A. (1998). "The fossil record and evolution of the Myriapoda". In Fortey, R. A.; Thomas, R. H. (eds.). Arthropod Relationships. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 211–220. ISBN 9789401149044.

- Brookfield, M.E.; Catlos, E.J.; Suarez, S.E. (2020). "Myriapod divergence times differ between molecular clock and fossil evidence: U/Pb zircon ages of the earliest fossil millipede-bearing sediments and their significance". Historical Biology: 1–5. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1762593.

- Dunham, W. (30 May 2020). "Millipede from Scotland is world's oldest-known land animal". Reuters. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Almond, J.E.; Lawson, J.D. (1985). "The Silurian-Devonian fossil record of the Myriapoda". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 309 (1138): 227–237. doi:10.1098/rstb.1985.0082.

- Wilson, H.M.; Anderson, L.I. (2004). "Morphology and taxonomy of paleozoic millipedes (Diplopoda: Chilognatha: Archipolypoda) from Scotland". Journal of Paleontology. 78 (1): 169–184. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2004)078<0169:MATOPM>2.0.CO;2.