Karasahr

Karasahr or Karashar (Uyghur: قاراشەھەر, romanized: Qarasheher), which was originally known in the Tocharian languages as Ārśi (or Arshi), Qarašähär, or Agni or the Chinese derivative Yanqi (Chinese: 焉耆; pinyin: Yānqí; Wade–Giles: Yen-ch'i), is an ancient town on the Silk Road and the capital of Yanqi Hui Autonomous County in the Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang.

Karasahr

Qarasheher Ārśi; Yanqi; Agni; Kara Shahr; Yenki | |

|---|---|

Town | |

| Karashar | |

Karasahr downtown mosque | |

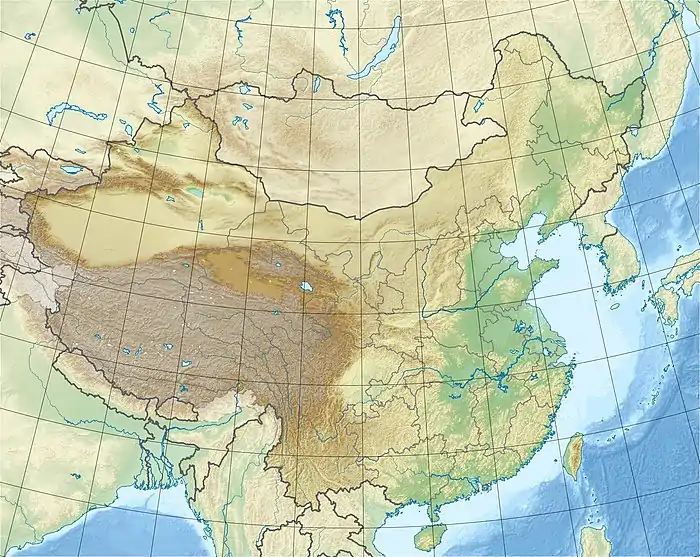

Karasahr Location in Xinjiang  Karasahr Karasahr (China) | |

| Coordinates: 42°3′31″N 86°34′6″E | |

| Country | China |

| Autonomous region | Xinjiang |

| Autonomous prefecture | Bayin'gholin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture |

| Autonomous county | Yanqi |

| 29000 | |

As of the 2000 census it had a population of 29,000,[1] growing to 31,773 people in 2006; 16,032 persons of which were Han, 7781 people Hui, 7154 people Uyghur, 628 Mongol and 178 other ethnicities and an agricultural population of 1078 people.

The town has a strategic location, being located on the Kaidu River (known in ancient times as the Liusha), China National Highway 314 and the Southern Xinjiang Railway and is an important material distribution center and regional business hub. The town administers ten communities.[1] It has a predominately Muslim population and contains many mosques.

Geography

The modern town of Yanqi is situated about 24 kilometres (15 mi) west of the shallow Lake Bosten. The lake is about 81 kilometres (50 mi) east to west and 48 kilometres (30 mi) north to south with a surface area of about 1,000 square kilometres (390 sq mi), making it one of the largest lakes in Xinjiang. It has been noted since Han times for its abundance of fish. The lake is fed by the Kaidu River and the Konqi River[lower-alpha 1] flows out of it past Korla and across the Taklamakan Desert to Lop Nur. There are numerous other small lakes in the region.

The city, referred to in classical Chinese sources as Yanqi, was located on the branch of the Silk Route that ran along the northern edge of the Taklamakan Desert in the Tarim Basin.

History

The earliest known inhabitants of the area were an Indo-European people who apparently referred to themselves and the city as Ārśi (pronounced "Arshi"). Their language, since it was rediscovered in the early 20th century, has been known as "Tocharian A" (a misnomer resulting from an assumed relationship to the Tukhara of Bactria). The people and city were also known as Agni, although this may have been a later exonym, derived from the word for "fire" in an Indo-Iranian language such as Sanskrit (cognate to English "ignite"). The 7th century Buddhist monk Xuanzang transliterated Agni into Chinese as O-ki-ni 阿耆尼 (MC ZS: *ʔɑ-ɡiɪ-ɳˠiɪ standard: Āqíní).[2][3]

Ārśi was bordered by related Tocharian cultures, many of which also spoke related languages: Kuča (or Kucha), Gumo (later Aksu) to the west, Turfan (Turpan) to the east and to the south, Krorän (Loulan).

In China, Han dynasty sources describe Yanqi (Ārśi / Agni) as a relatively large and important neighboring kingdom. According to Book of Han, the various states of the "Western Regions", including Yanqi, were controlled by the nomadic Xiongnu, but later came under the influence of the Han dynasty, following a Han show of force against Dayuan (Fergana) in the late 2nd century BCE.[4]

From the 1st century BCE onwards, many populations in the Tarim Basin, including the Ārśi underwent conversion to Buddhism and, consequently, linguistic influence from Indo-Iranian languages, such as Pali, Sanskrit, Bactrian, Gandhari and Khotanese (Saka). The city of Ārśi became commonly known as Agni, almost certainly derived from the Sanskrit अग्नि "fire". Names such as Agnideśa (अग्निदेश) and Agni-visaya, both of which are Sanskrit for "city of fire", are also recorded in Buddhist scriptures.

According to the Book of the Later Han, General Ban Chao went on a punitive campaign against Yanqi in 94 CE after they attacked and killed the Protector General Chen Mu and Vice Commandant Guo Xun in 75 CE. The king of Yanqi was decapitated and his head displayed in the capital. Later rebellions were subdued by Ban Chao's son Ban Yong in 127 CE.

- It has "15,000 households, 52,000 individuals, and more than 20,000 men able to bear arms. It has high mountains on all four sides. There are hazardous passes on the route to Qiuci (Kucha) that are easy to defend. The water of a lake winds between the four mountains, and surrounds the town for more than 30 li [12.5 km]."[5]

Agnideśa became a tributary state of Tang China in 632 CE. In 644, during the Tang expansion into the Tarim Basin, Emperor Taizong of Tang launched a military campaign against Yanqi after the kingdom allied itself with the Turks. The Four Garrisons of Anxi was established with one based at Yanqi.

According to Book of Zhou (636 CE) the kingdom of Yanqi (Karashahr) was a small country with poor people and nine walled towns, and described the country and their custom thus:[6]

- Marriage is about the same as among the Chinese. All the deceased are cremated and then buried. They wear mourning for seven full days, after which they put it off. The adult men all trim their hair to make a head decoration. Their written characters are the same as those of India.

- It is their custom to serve "Heavenly God(s)" but they also show reverence and trust in the doctrines of the Buddha. They especially celebrate these days: The eighth day of the second month, and the eighth day of the fourth month. All the country abstains and does penance according to the teachings of Śākya, and follows His Way.

- The climate is cold, and the land good and fertile. For cereals, they have rice, millet, pulse, wheat, and barley. For animals, they have camels, horses, cows, and sheep. They raise silk-worms but do not make silk, merely using [the silk fiber] for padding. It is their custom to relish grape wine, and also to love music. It is some ten li north of a body of water, and has an abundance of fish, salt, and rushes. In the fourth year of the period Pao-ting, its king sent an envoy to present its renowned horses.[6][7]

By the mid-9th century, the area had been conquered by the Uyghur Khaganate and the Tocharian languages were fading from use. Agnideśa became widely known by the Uyghur Turkic name Karasahr (or Karashar), meaning "black city". The influence of Islam grew, while older religions such as Buddhism and Manichaenism declined.

Between the mid-13th century and the 18th century, Karasahr was part of the Mongol Chagatai Khanate.

Karashahr may have been known to late medieval Europeans as Cialis, Chalis, or Chialis,[lower-alpha 2] although Korla, Krorän, and other city names are instead favored by some scholars.

In the early 17th century, the Portuguese Jesuit lay brother Bento de Góis visited the Tarim Basin on his way from India to China (via Kabul and Kashgar). De Góis and his traveling companions spent several months in the "Kingdom of Cialis", while crossing it with a caravan of Kashgarian merchants (ostensibly, tribute bearers) on their way to Ming China. The travelers stayed in Cialis City for three months in 1605, and then continued, via Turpan and Hami (all parts of the "Kingdom of Cialis", according to de Góis), to the Ming border at Jiayuguan.[12][13][14]

The British traveller Francis Younghusband briefly visited Karasahr in 1887 on his overland journey from Beijing to India. He described it as being "like all the towns hereabouts, is surrounded by a mud wall, and the gateways are surmounted by the usual pagoda-like towers. There is a musketry wall round outside the main wall, but it is now almost in ruins. Inside the wall are some yamens, but only a few houses. Outside, to the south, are a few shops and inns."[15]

An early-20th-century traveler described the situation in Karashahr as follows:

- "The whole of this district round Kara-shahr and Korla is, from a geographical and political point of view, both interesting and important; for whilst all other parts of Chinese Turkestan can only be reached either by climbing high and difficult passes—the lowest of which has the same elevation as Mont Blanc—or traversing extensive and dangerous waterless deserts of sand-hills, here we find the one and only convenient approach to the land through the valleys of several rivers in the neighbourhood of Ili, where plentiful water abounds in the mountain streams on all sides, and where a rich vegetation makes life possible for wandering tribes. Such Kalmuck tribes still come from the north-west to Tal. They are Torgut nomads who pitch their yurts round about Kara-shahr and live a hard life with their herds ...

- Just as these Mongols wander about here at the present day, so the nomadic tribes of an earlier period must have used this district as their entrance and exit gate. The Tochari (Yue-chi) [Pinyin: Yuezhi], on their way from China, undoubtedly at that time passed through this gate to get into the Ili valley ..."[16]

Rulers

(Names are in modern Mandarin pronunciations based on ancient Chinese records)

- Shun (舜) 58

- Zhong (忠) 88

- Guang (廣) 91

- Yuan Meng (元孟) 94–127

- Long An (龍安) 280

- Long Hui (龍會) 289

- Long Xi (龍熙) 306

- Long Jiushibeina (龍鳩屍卑那) 385

- Tang He (唐和) 448

- Che Xie (車歇) 449

- Qu Jia (麴嘉) 497

- Long Tuqizhi (龍突騎支) 605

- Long Lipozhun (龍栗婆准) 644

- Long Xuepoanazhi (龍薛婆阿那支) 645

- Long Xiannazhun (龍先那准) 649

- Long Tuqizhi (龍突騎支) 650

- Long Nentu (龍嫩突) 651

- Long Yantufuyan (龍焉吐拂延) 719

- Long Chang'an (龍長安) 737

- Long Tuqishi (龍突騎施) 745

- Long Rulin (龍如林) 767–789? / Tang general – Yang Riyou 789

Footnotes

References

- www.xzqh.org (in Chinese)

- Saran (2005, p. 61)

- Xuanzhang. Great Tang Records of the Western Regions "vol. 1"

- Hulsewé, A.F.P. (1979). China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: An annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the history of the former Han dynasty. Leiden, NL: E. Brill. pp. 73–80. ISBN 90-04-05884-2.

- Book of the Later Han cited by Hill (2009, pp. 45, 427–431).

- Linghu Defen. Zhou Shu [Book of Zhou].

- Miller, Roy Andrew, ed. (1959). Accounts of Western Nations in the History of the Northern Chou Dynasty. Translated by Miller. University of California Press. pp. 9–10.

- Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). The History of Central Asia. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2, in 4 volumes.

- Whitfield, Susan (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, travel, war, and faith. British Library / Serindia Publications. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- Ricci, Matteo (1615). Trigault, Nicolas (ed.). De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta ab Societate Jesu [On the Christian Mission among the Chinese by the Society of Jesus] (in Latin). Augsburg, DE. There is also Ricci, Matteo; Trigault, Nicolas (1617). full Latin text available – via Google Books.

- Fang, Zhaoying (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03801-1.

- Goodrich, Luther Carrington; Fang, Zhaoying (1976). "Bento de Góis". Dictionary of Ming Biography. Vol. 1: 1368–1644. Columbia University Press. pp. 472–473. ISBN 0-231-03801-1.

- Dughlt, Mirza Muhammad Haidar (2008). A History of the Moghuls of Central Asia: The Tarikh-I-Rashidi. Cosimo. ISBN 978-1-60520-150-4.

- Gallagher, Louis J., ed. (1953). "Cathay and China proved to be identical". China in the Sixteenth Century: The journals of Mathew Ricci: 1583–1610. Translated by Gallagher. New York: Random House. book 5, chapter 12, pages 510-513. — This is an English translation of a 1615 Latin work by Ricci & Trigault.[10]

- Younghusband, Francis E. (2005) [1896]. The Heart of a Continent (facsimile reprint ed.). London, UK: Elbiron Classics. pp. 143–144, ISBN 1-4212-6551-6 (pbk), ISBN 1-4212-6550-8 (hdcv).

- von Le Coq, A. (1985) [1928]. Buried Treasures of Chinese Turkestan: An account of the activities and adventures of the second and third German Turfan expeditions. Translated by Barwell, Anna (Reprint ed.). London: Oxford University Press. pp. 145–146.

Sources

- Hill, John E. (2004). The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A third century Chinese account composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A study of the silk routes during the later Han dynasty, 1st to 2nd centuries CE. Charleston, SC: BookSurge. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Puri, B.N. (2000) [1987]. Buddhism in Central Asia. (reprint ed.) Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

- Saran, Mishi (2005). Chasing the Monk's Shadow: A journey in the footsteps of Xuanzang. New Delhi: Penguin / Viking. ISBN 0-670-05823-8.

- Stein, Aurel M. (1990) [1912]. Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal narrative of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, 2 vols. (reprint ed.) Delhi, IN: Low Price Publications.

- Stein, Aurel M. (1980) [1921]. Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in central Asia and westernmost China, 5 vols. (orig ed.) London & Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. (reprint ed.) Delhi, IN: Motilal Banarsidass.

- Stein Aurel M. (1981) [1928]. Innermost Asia: Detailed report of explorations in central Asia, Kan-su and eastern Iran, 5 vols. (orig ed.) Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. (reprint ed.) New Delhi, IN: Cosmo Publications.

- Yu, Taishan (March 2004). A History of the Relationships between the Western and Eastern Han, Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties, and the Western Regions. Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. Sino-Platonic Papers. Vol. 131. University of Pennsylvania.

External links

- Silk Road Seattle - University of Washington (The Silk Road Seattle website contains many useful resources including a number of full-text historical works, maps, photos, etc.)