Kashmir Sultanate

The Kashmir Sultanate (Kashmiri: ریاست کشمیر Riyāsat-e-Kashmīr, Persian: سلطنت کشمیر Saltanat-e-Kashmīr) or historically latinized as Sultanate of Cashmere, was a medieval Indo-Islamic kingdom established in the early 14th century in Northern India, primarily in the Kashmir Valley. The sultanate was founded by Rinchan Shah, a Ladakhi noble who converted from Buddhism to Islam. The sultanate was briefly interrupted by the Loharas until Shah Mir, a councillor of Rinchan, overthrew the Loharas and started his own dynasty. The Shah Mirs ruled from 1339 until they were deposed by the Chak warlords and nobles in 1561. The Chaks continued to rule the sultanate until the Mughal conquest in 1586 and their surrender in 1589.

Sultanate of Kashmir | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1320–1323 1339–1589 | |||||||||||

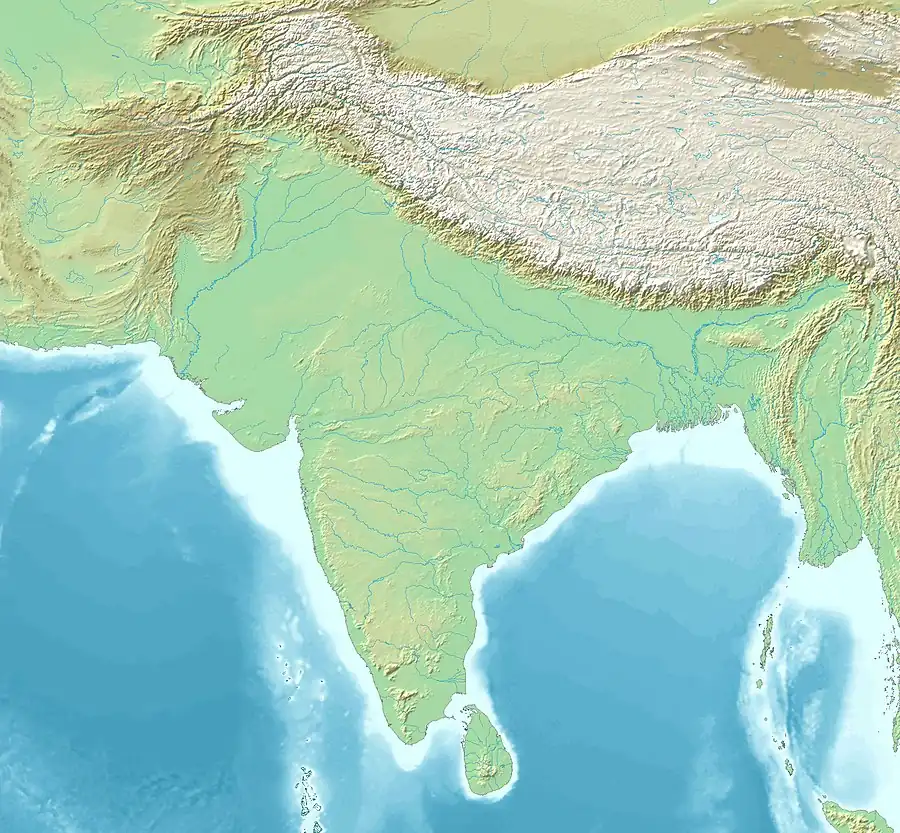

◁ ▷ The Kashmir Sultanate under Shah Mir dynasty and contemporary South Asian polities in 1400 CE.[1] | |||||||||||

| Status | Sultanate | ||||||||||

| Capital | Srinagar (1320–1323) (1339–1343) (1354–1470) (1472–1529) (1530–1586) Andarkot (1343–1354) Sikandarpur (1470–1472) Naushahra (1529–1530) Chandrakot (1586–1587) Varmul (1587–1588) Suyyapur (1586–1588) no centralised capital (1588–1589) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Persian Kashmiri Dardic Arabic | ||||||||||

| Religion | State religion: Sunni Islam (Shafi) (1320–1561) Shia Islam (Imamiyya) (1561–1589) Minority religions: Hinduism Buddhism | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Kashmiri | ||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||

• 1320–1323 (first) | Sadr'ud-Din Shah | ||||||||||

• 1586–1589 (last) | Yakub Shah Chak | ||||||||||

| Wazir | |||||||||||

• 1320–1323 (first) | Tukka | ||||||||||

• 1586–1589 (last) | Nazuk Bhat | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval India | ||||||||||

• Conversion of Rinchan Shah | 1320 | ||||||||||

• Lohara Interruption | 1323–1339 | ||||||||||

• Shah Mir–Lohara Conflict | 1339 | ||||||||||

• Shah Mir Civil War | 1419–1420 | ||||||||||

• Babur's expedition | 1523 | ||||||||||

• Kashgar–Kashmir War | 1533 | ||||||||||

• Second Mughal invasion | 1540–1551 | ||||||||||

• Annexation | 1546 | ||||||||||

• Restoration | 1551 | ||||||||||

• Third Mughal invasion | 1585–1586 | ||||||||||

• Battle of Hastivanj | 1586 | ||||||||||

• War of Independence | 1586–1589 | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1323 | 22,000 km2 (8,500 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Currency | Gold Dinar, Silver Sasnu, Bronze Kasera | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | India Pakistan | ||||||||||

The Kashmir Sultanate was a Muslim monarchy with Kashmiri, Turco-Persian, Dardic, and Ladakhi elites. A Ladakhi Muslim, Rinchan Shah, served as the first Sultan and was followed by the two prominent dynasties, Shah Mir and Chak dynasty. A Baihaqi Sayyid, Mubarak Baihaqi, briefly ruled the Sultanate after overthrowing Yousuf Chak in 1579. Due to the diversity, the kingdom worked on the principles of Kashmiriyat, containing and existing between the proximites of the cultural and religious pluralism. Even though Persian was favoured upon as the official, diplomatic, and state language, Kashmiri still had a large impact on the social and communal work and was later granted official status. The economical center as well as the vital mint city of the sultanate, Srinagar, served as the capital for the majority of its lifespan while the diverse city of Varmul, the highly rich and cultivated land of Suyyapur, the hilly areas of Anantnag and the surrounding valleys of Neelum were the notable commercial and residential districts. The sultanate carried out major trading relations, having establishments in Bihar, Tibet, Nepal, Peking, Bhutan, Khurasan, and Turkestan whereas Punjab and Bengal were considered her greatest trading and industrial partners. Besides Delhi Sultanate, Kashmir, along with Bengal, Gujarat, and Sindh, were considered strong political and martial allies, even interfering in one another's internal problems.

During the sultanate era, the valley was influenced by various orders of Sufism and mysticism. The Suhrawardiyya, Kubrawiya, Rishi, and Nurbakhshiya orders were formally adopted and regulated by the Sultans in their reign. A form of peace culture evolved around the Kashmiri Pandits and Muslims in the leadership and teachings of Lal Ded, Nund Rishi, Habba Khatun, Yaqub Ganai and, Habibullah Ganai. With the beginning of the Muslim epoch, Indo-Islamic architecture was observed along with the Kashmiri architecture evolving into the Islamic Kashmiri style of infrastructure and designing. This style can still be seen in the old muhallahs of Srinagar.

History

Background (13th and 14th centuries)

Numerous attempts had been made to conquer Kashmir first by the Arabs in the 7th and 8th century and then by the Turks in the 11th century[2] but it was not until the reigns of Mahmud of Ghazni and Muhammad of Ghor that Kashmir looked out to serious threats of invasion.[3][4] It was at this time that Turkic and Tajik traders entered Kashmir and were allowed to serve in the Lohara army.[5] With the Hindu emperors weakened, Kashmir became a subject to the Mongol invasions in the 13th century.[6] Unable to fend off the invasions this time, Kashmir became a Mongol dependency some time after 1235.[7] In 1320, a Mongol commander, Zulju, with an army of Qara'unas, entered Kashmir and, after all types of atrocities and violence,[8][6] left the valley with the loot. As Emperor Suhadeva fled to Kishtwar, the valley passed on to the hands of local chiefs who asserted independence.[9][10] The most prominent of them were Ramacandra, the commander-in-chief of Suhadeva, and Rinchan Bhoti, a Ladakhi Buddhist noble, who left Ladakh after his father, a Ladakhi chief, was killed by the Baltis.[11] Rinchan, who founded no one more powerful than him after he had killed Ramacandra in a surprise attack, ascended the throne as Rinchan Shah.[12]

The first challenge faced by Rinchan was to gain the trust of the public and of the nobles.[13] For that, he released Ramacandra's son, Rawancandra, and his family and granted him the title of Raina (Lord) with some jagirs. He also appointed him his Mir Bakhshi (Commander-in-Chief) and married his sister, Kota Rani, who had previously been the Empress consort of Suhadeva.[14][15] After suppressing this provocation, Rinchan faced Suhadeva, who had returned to the valley after Zulju's departure. He tried to subdue the people against Rinchan but was repulsed as the people still remembered his betrayal.[16][17] Soon after these events, the Lavanyas, a feudal tribe, challenged Rinchan but were defeated and forced to acknowledge him.[18]

The Emperor always had a coucil of cultured men and artisans in his court along with Muslim scholars and Hindu and Buddhist priests.[19] With an elusive yet sharp mind, Rinchan later in the same year in the hands of Bulbul Shah and adopted the title of Sultan Sadr'ud-Din, becoming the first Sultan of Kashmir.[20][21] Rawancandra also accepted Islam and became a close associate of the Sultan.[22] Shah Mir, a Turkish migrant from Swat who settled in Kashmir in 1313 with his family, also entered the government of the Sultan and was a trusted councillor of the Sultan.[23] He even appointed him as the tutor of his son Haidar.[24][25] Sultan Sadr'ud-Din faced a surprise attack by Tukka, his former Vizier, and his followers. The preparators left a serious wound on the Sultan's head in between the struggle[26] but was rescued by his Vizier, Vyalaraja. The Sultan took the enemies by surprise and executed them. He also ripped open the wombs of their wives by the sword.[27]

Unluckily, the wound on the Sultan's head proved fatal, and he died in 1323.[26] He was buried near the Mosque he had built in Srinagar. After the Sultan's demise, Udayanadeva, the brother of Suhadeva, was called back from Swat to claim the throne on the orders of Kota Rani and the consent of Shah Mir and other nobles as Haidar was still a minor.[28][29]

Early Years (14th Century)

The rule of Udayanadeva lasted until his death in 1338 and was succeeded by his wife Kota Rani.[30][31] Shah Mir, in the meantime, strengthened his position in the cabinet of Udayanadeva.[32][29] Kota Rani appointed Bhatta Bhiksana, a powerful minister, as her Prime Minister, ignoring Shah Mir. She also moved her capital to Andarkot as Srinagar was, at that time, Shah Mir's stronghold.[33][34] This angered Shah Mir, who, at once, marched against her. Through a conspiracy, he assassinated Bhiksana and threatened Kota Rani to surrender and marry him.[35] Kota Rani, after seeing her troops and chiefs deserting her, reluctantly agreed. Shah Mir, at first, married her but, seeing the support she had in the kingdom, threw her and her children in prison while he himself ascended the throne as Sultan Shamsu'd-Din Shah.[36][37]

With the behest of the new rule, a new era, namely, the Kashmiri era, replaced the old Laukika era established by the Hindu Emperors.[38] Shamsu'd-Din set up Islamic roots in the early stages of the Sultanate,[39][40] appointing Muslim converts from Chak and Magre clan to major posts in the government.[41] After his death in 1342, the Sultanate passed on to Shamsu'd-Din's sons, Jamshid and Ali Sher.[42][43]

References

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 147, map XIV.3 (c). ISBN 0226742210.

- Mohibbul Hassan. Kashmir Under The Sultans Mohibbul Hassan. p. 27.

- Nazim, Muhammad (1 January 2015). The Life and Times of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna (Revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 92–3. ISBN 978-1-107-45659-4.

- Mohibbul Hassan. Kashmir Under The Sultans Mohibbul Hassan. p. 28.

- Marc Aurel Stein (1900). Kalhana's Rajatarangini Vol 1. pp. 107–119.

- Mohibbul Hassan. Kashmir Under The Sultans Mohibbul Hassan. p. 34.

- al-Uthmani, Minhaj al-Din ibn Umar; Raverty, H. G. (13 August 2010). Tabakat-i-Nasiri. Gorgias Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-61719-755-0.

- Chādūrah, Ḥaydar Malik (1991). History of Kashmir. Delhi: Bhavna Prakashan. pp. 96a-b.

- Chādūrah, Ḥaydar Malik (1991). History of Kashmir. Delhi: Bhavna Prakashan. pp. 31b–32a.

- Mohibbul Hassan. Kashmir Under The Sultans Mohibbul Hassan. p. 36.

- Mohibbul Hassan. Kashmir Under The Sultans Mohibbul Hassan. p. 37.

- Dutt, Jogesh Chunder (1 January 2012). Rajatarangini of Jonaraja. New Dehli: Gyan Publishing House. p. 18. ISBN 978-81-212-0037-0.

- Mohibbul Hassan. Kashmir Under The Sultans Mohibbul Hassan. p. 38.

- BAHARISTAN E SHAHI. pp. 12b.

- Chādūrah, Ḥaydar Malik (1991). History of Kashmir. Delhi: Bhavna Prakashan. pp. 99a.

- BAHARISTAN E SHAHI. pp. 13a.

- Chādūrah, Ḥaydar Malik (1991). History of Kashmir. Delhi: Bhavna Prakashan. pp. 100a.

- Dutt, Jogesh Chunder (1 January 2012). Rajatarangini of Jonaraja. New Dehli: Gyan Publishing House. p. 19. ISBN 978-81-212-0037-0.

- Mohibbul Hassan. Kashmir Under The Sultans Mohibbul Hassan. p. 39.

- Hassan Gulam Khuihami (1911). Tarikh E Hasan Vol I. pp. 136b.

- BAHARISTAN E SHAHI. pp. 14b.

- Mohibbul Hassan. Kashmir Under The Sultans Mohibbul Hassan. p. 40.

- BAHARISTAN E SHAHI. pp. 16a.

- Chādūrah, Ḥaydar Malik (1991). History of Kashmir. Delhi: Bhavna Prakashan. pp. 104a.

- Muhammad Arif Qandhari, active 1577 (1993). Tarikh-i-Akbari. Internet Archive. Delhi : Pragati Publications. p. 425. ISBN 978-81-7307-013-6.

- Dutt, Jogesh Chunder (1 January 2012). Rajatarangini of Jonaraja. New Dehli: Gyan Publishing House. p. 23. ISBN 978-81-212-0037-0.

- Mohibbul Hassan. Kashmir Under The Sultans Mohibbul Hassan. p. 41.

- Dutt, Jogesh Chunder (1 January 2012). Rajatarangini of Jonaraja. New Dehli: Gyan Publishing House. p. 24. ISBN 978-81-212-0037-0.

- BAHARISTAN E SHAHI. pp. 16a.

- Dutt, Jogesh Chunder (1 January 2012). Rajatarangini of Jonaraja. New Dehli: Gyan Publishing House. p. 28. ISBN 978-81-212-0037-0.

- Mohibbul Hassan. Kashmir Under The Sultans Mohibbul Hassan. p. 42.

- Dutt, Jogesh Chunder (1 January 2012). Rajatarangini of Jonaraja. New Dehli: Gyan Publishing House. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-81-212-0037-0.

- BAHARISTAN E SHAHI. pp. 17a.

- Chādūrah, Ḥaydar Malik (1991). History of Kashmir. Delhi: Bhavna Prakashan. pp. 105b.

- Dutt, Jogesh Chunder (1 January 2012). Rajatarangini of Jonaraja. New Dehli: Gyan Publishing House. p. 29. ISBN 978-81-212-0037-0.

- Mohibbul Hassan. Kashmir Under The Sultans Mohibbul Hassan. pp. 43–44.

- Dutt, Jogesh Chunder (1 January 2012). Rajatarangini of Jonaraja. New Dehli: Gyan Publishing House. p. 32. ISBN 978-81-212-0037-0.

- Asrar Alakhyar. Tarikh E Hassan Vol 3 Asrar Alakhyar. pp. 85b.

- Dutt, Jogesh Chunder (1 January 2012). Rajatarangini of Jonaraja. New Dehli: Gyan Publishing House. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-81-212-0037-0.

- Muhammad Arif Qandhari, active 1577 (1993). Tarikh-i-Akbari. Internet Archive. Delhi : Pragati Publications. pp. 426 (Vol III). ISBN 978-81-7307-013-6.

- Mohibbul Hassan. Kashmir Under The Sultans Mohibbul Hassan. p. 46.

- Dutt, Jogesh Chunder (1 January 2012). Rajatarangini of Jonaraja. New Dehli: Gyan Publishing House. p. 33. ISBN 978-81-212-0037-0.

- Muhammad Arif Qandhari, active 1577 (1993). Tarikh-i-Akbari. Internet Archive. Delhi : Pragati Publications. pp. 427 (Vol III). ISBN 978-81-7307-013-6.