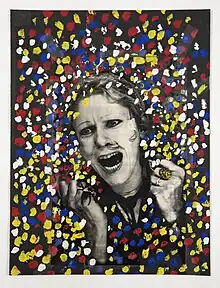

Kate Manheim

Kate Manheim is an American visual artist and performer based in New York. Although she has focused on her practice as a painter since the 1990s,[1] she is also well-known for her work as an actress with her collaborator and husband, the director Richard Foreman.

Personal life

Manheim was born in 1945 in the Bronx, New York City,[2] the daughter of the German Jewish translator Ralph Manheim.[3] She spent much of her childhood in France.[4] At a young age she studied painting at “Academie de Jedui” run by the Swiss artist Arno Stern, and participated in sketching sessions at the Academie de la Grand Chaumiere.[5] She returned to the United States in 1969 and got a job teaching French and English at Berlitz, followed by a brief stint in the accounting department of a student exchange organization. When she met Richard Foreman in 1971, she was working as a film librarian at the Public Theater's Anthology Film Archives, when Foreman walked in looking for actors to cast in his play Hotel China. Foreman and Manheim began living together a year later, in 1972, at their Wooster Street loft and performance space; and they continued to work together on nearly all his productions until 1987. Manheim also translated Foreman's plays into French for productions in Paris. In addition to acting, Manheim continued her interest in painting through the 1980s.[2]

Manheim is married to the experimental theatre director Richard Foreman.

Career

Prior to working with Richard Foreman, Manheim had no acting experience,[6] "aside from a few small television roles...in France".[2] Through her work with Foreman, she became a fixture in New York and Paris’ avant-garde theater scenes, with lead roles in many productions by Richard Foreman, as well as Jean Jourdheuil and Jean-Francois Peyret, and collaborating frequently with filmmaker Jack Smith. [5]

Manheim was the lead actress in most of Richard Foreman's theatre works, as well as a number of his films, between 1972 and 1987, almost always playing a character called Rhoda. Her first appearance was in his 1972 play Hotel China,[7] and her last appearance was in his 1987 play Film is Evil: Radio is Good. Foreman has stated that his collaborations with Manheim had a strong influence on the development of his work.

The introduction of such playfulness and fantasy was also due to the influence of Kate Manheim, who was the leading performer in these plays for many years. Simply put, Kate is a more playful person than I, and it was she who wanted to do playful things onstage. It interested her to take off her clothes, to be shocking and provocative in performance, which not only funneled much erotic imagery directly into the work, but also encouraged its broader free play and inventiveness.[8]

What's interesting is that she brought something to my work that I would have rejected. She came to America and got hooked on all these television serials that I would never deign to watch. She loved I Love Lucy and The Honeymooners and so forth, and the injection of that kind of energy into my pretensions of rarefied intellectual art has been tremendously healthy.[2]

Manheim also attributes to her influence Foreman's shift to using real spoken dialogue in his plays, rather than the pre-recorded dialogue used in his early work: "I felt I wanted to talk."[2]

In a 1987 interview, Manheim described her work with Foreman as deeply collaborative, but also emotionally fraught.

When I started working for [Richard Foreman] I was in a position where I did everything I was told. I did not question that--at the time. Now I'm in a position where I systematically refuse to do anything I'm told. Of course, Richard's still the director...My contribution vanishes. Richard still has a written text that can be published. I have nothing. Furthermore, I've just been living through hell for the last five months. Every day I go to a place of work where all I can do is disagree with everything that's being done. I don't get along with Richard very well, I don't get along with the other actors. And now I find myself crying most of the day, waiting for the performance. I sort of pull myself together to do the play because somewhere in myself I'm reliable...Even though a play like [Film is Evil: Radio is Good] just wouldn't have existed if I hadn't been around...I used to say that these plays were soap operas of the life of Richard Foreman and Kate Manheim. They are very autobiographical, even though a lot of it we don't think of, it's just there in the texture of it, in the words. So I just kept at Richard to make it mold to my unconscious of the moment.[6]

Manheim left acting in 1987 to return to her career as a visual artist, enrolling at the Cooper Union in New York.[5] She has since created over 600 paintings.[3] The composer John Zorn wrote that Manheim's paintings “speak to the human psyche directly in languages both angelic and demonic.”[9]

Manheim's work has been widely exhibited. She had a solo exhibition curated by John Zorn at the Cue Foundation, New York in 2008, and a solo exhibition at Anthology Film Archives’ Court House Gallery in 1996,[5] which featured a lifetime's work of artwork from childhood paintings of Christ to the "grief portraits" of her mother who died in 1985.[3] Her work was included in ‘Looking Back: The Third White Columns Annual’ selected by curator Jay Sanders in 2008 at White Columns, a gallery in New York City. In 2015, Manheim had a solo exhibition at White Columns.[5] Her work was included in the group exhibitions Weathering at Kai Matsumiya in New York (2022) and You've Got To Be Here! at Galeria lokal_30 in Warsaw, Poland.[10]

Acting Credits

Theatre

All works written and directed by Richard Foreman unless otherwise specified.

- HcOhTiEnLa (or) Hotel China, New York City (1971)[11]

- Sophia= (Wisdom) Part 3: The Cliffs, New York City (1972)[11]

- Particle Theory, New York City (1973)[12]

- Pain(t), New York City (1974)[11]

- Pandering to the Masses: A Misrepresentation, New York City (1975)[13]

- Rhoda in Potatoland (Her Fall-Starts), New York City (1975)

- Livre des Splendeurs: Part One, Paris (1976)[14]

- Book of Splendors: Part Two (Book of Levers) Action at a Distance, New York City (1977)[15]

- Blvd. de Paris (I've Got the Shakes), New York City (1977)[16]

- Penguin Touquet, New York City (1981)[8]

- Café Amérique, Paris (1981)[17]

- Three Acts of Recognition by Botho Strauss, dir. Richard Foreman, Paris (1982)[6]

- Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights by Gertrude Stein, dir. Richard Foreman, Paris (1982)[18]

- Egyptology, New York City (1983)[19]

- La Robe de Chambre de Georges Bataille, Paris (1983)[20]

- Medea by Heiner Müller, dir. Jean Jourdheuil, Theatre de l'Odéon, Paris (1983)[6]

- The Birth of the Poet by Kathy Acker, dir. Richard Foreman, Rotterdam (1983)[6]

- My Life, My Death by Pier Paolo Pagolini by Kathy Acker, dir. Richard Foreman, Paris (1984)[6]

- The Park by Botho Strauss, dir. Claude Regie, Paris (1985)[6]

- The Cure, New York City (1986)[8]

- Film Is Evil: Radio Is Good, New York City (1987)[8]

Film

- Paul, 1969, dir. Diourka Medveczky

- 'Rameau's Nephew' by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen, 1974, dir. Michael Snow

- What Maisie Knew, 1975, dir. Babette Mangolte

- Strong Medicine, dir. Richard Foreman, 1978

References

- "Zalle, David. "Kate Manheim."BOMB Magazine #95: Artists on Artists Issue, April 1, 2001".

- Ellen. August 16, 1983. "Kate Manheim: I Don't Need No Teacher." Village Voice. https://archive.org/details/village-voice-kate-manheim/title=Rapp, Ellen. August 16, 1983. "Kate Manheim: I Don't Need No Teacher." Village Voice.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Kate Manheim". cueartfoundation.org. 2008.

- Swettenham, Neal (2017). Richard Foreman: An American (Partly) in Paris. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1351594966.

- "Press Release. White Columns. 2015".

- "Schechner, Richard and Kate Manheim. "Talking with Kate Manheim: Unpeeling a Few Layers: An Interview." MIT Press, The Drama Review: TDR , Winter, 1987, Vol. 31, No. 4 (Winter, 1987), pp. 136- 142".

- "Guide to the Richard Foreman Papers: 1942-2004 (Bulk 1969-2004) MSS.152. Fales Library and Special Collections. New York University, 2022".

- Foreman, Richard. Unbalancing Acts: Foundations for a Theater. New York: Pantheon Books, 1992, 86-7.

- "Kate Manheim".

- "Kate Manheim: Biography. Mutual Art".

- "Richard Foreman. George Hunka, 2022".

- "Florence A. Falk. Physics and the Theatre: Richard Foreman's "Particle Theory". Educational Theatre Journal , Oct., 1977, Vol. 29, No. 3 (Oct., 1977), pp. 395-404".

- "Gussow, Mel. Jan 16, 1975. "Stage: Zesty 'Pandering.'" The New York Times".

- "Program for Richard Foreman's Livre des Splendeurs: Part One, Paris, 1976. www.festival-automne.com" (PDF).

- "Foreman, Richard. Book of Splendors: Part II (Book of Levers) Action at a Distance. Theater (1978) 9 (2): 79–89".

- "Eder, Richard. Dec. 24, 1977. "Play of Many Titles Follows Them All." The New York Times".

- "Program for Richard Foreman's Cafe Amerique, Paris, 1981. www.festival-automne.com" (PDF).

- "Savran, David. "Whistling in the Dark." Performing Arts Journal, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Jan., 1993), pp. 25-27".

- "Rich, Frank. May 18, 1983. THEATER: 'EGYPTOLOGY' BY RICHARD FOREMAN. The New York Times.".

- "Program for Richard Foreman's La Robe de Chambre de Georges Bataille, Paris, 1983. www.festival-automne.com" (PDF).