Katharine Wright Haskell

Katharine Wright Haskell (August 19, 1874 – March 3, 1929) was the younger sister of aviation pioneers Wilbur and Orville Wright. She worked closely with her brothers, managing their bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio, when they were away; acting as their right-hand woman and general factotum in Europe; assisting with their voluminous correspondence and business affairs; and providing a sounding board for their far-ranging ideas. She pursued a professional career as a high school teacher in Dayton, at a time when few middle-class American women worked outside the home, and went on to become an international celebrity in her own right. A significant figure in the early-twentieth-century women's movement, she worked actively on behalf of woman suffrage in Ohio and served as the third female trustee of Oberlin College.

Katharine Wright Haskell | |

|---|---|

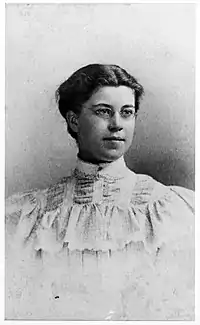

.jpg.webp) Wright in 1898 as a graduate of Oberlin College | |

| Born | August 19, 1874 Dayton, Ohio, US |

| Died | March 3, 1929 (aged 54) |

| Alma mater | Oberlin College (B. A., 1898) |

| Occupation | Teacher |

| Spouse |

Henry Joseph Haskell

(m. 1926–1929) |

Early years

Katharine Wright was born in Dayton, Ohio, on August 19, 1874, exactly three years after Orville Wright.[2] She was the youngest of five surviving children of Bishop Milton Wright and Susan Koerner Wright. When her mother died of tuberculosis in 1889, 14-year-old Katharine, as the only female child, was expected to fill her shoes. Throughout her teenage years and early adulthood, she pursued her education and teaching career while managing the home she shared with her father, an itinerant preacher, and older brothers. She was especially close to Wilbur and Orville, providing crucial moral and material support as they worked to solve the problem of powered human flight.[3] (The two oldest Wright brothers, Reuchlin and Lorin, left home while she was growing up.)

Katharine attended Central High School in Dayton and completed her secondary education at Oberlin Academy in 1893–94. After two years at what was then Oberlin's preparatory division, she attended Oberlin College, one of the few coeducational institutions in the United States at the time. The only Wright sibling to earn a college degree, she graduated in 1898, just shy of her twenty-fourth birthday.[4]

Katharine was exceptionally gifted, intellectually curious, and determined to become financially independent. Upon graduating from Oberlin, she took a position teaching Latin and English at Steele High School in Dayton. Although she found the work rewarding, she complained of earning less than her male colleagues and being assigned less desirable courses to teach.[4] This early experience of gender inequality in the workplace kindled a lifelong commitment to women's rights and education.[5] To assist with the household chores that she continued to perform on top of her full-time job, Katharine hired a teenage maid, Carrie Kayler, who would remain with the family for decades.[4]

Collaboration with brothers

The Wright Brothers, having neither independent resources nor government support, funded their aeronautical endeavors with earnings from their bicycle shop.[6] After they began spending summers at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in 1901, Katharine not only helped run the shop but packed supplies for their experiments and handled their official correspondence and relations with the press.[7] As Wilbur and Orville's efforts to market the Wright Flyer took them to Washington, D.C., and Europe, Katharine wrote hundreds of letters in which she kept them abreast of the progress of the family businesses, as well as personal and hometown news. She often scolded her unmarried brothers when they failed to keep up their end of the correspondence and warned them against amorous liaisons and other “distractions” that lay in wait for them abroad. Many of Katharine's letters from this and later periods are available as digital scans on the Library of Congress website. (See external links section).

In 1908, after nearly three years of trying, the brothers convinced the U.S. Signal Corps to allow them to test their Flyer for possible sale to the US government at Fort Myer, Virginia. Orville was the pilot for the demonstrations. After a week of successful and record-breaking flights, disaster struck: on September 17, 1908, a split propeller sent the airplane out of control. The ensuing crash killed the passenger, U.S. Army Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge, and seriously injured Orville, who suffered broken ribs and a broken leg. Katharine took emergency leave from her teaching job and rushed to his bedside at an Army hospital in northern Virginia. She rarely left Orville's room during his seven-week recuperation and never returned to the career that had given her both intellectual satisfaction and an independent income.[8] Orville later said that he would have died without his sister's aid. In the aftermath of the crash, Katharine helped her brothers negotiate a one-year extension of their contract with the Signal Corps.[6]

Katharine was not the only woman contributing important assistance to the brothers. In 1910 they advertised for someone to do 'plain sewing'. They actually meant 'plane sewing' as they needed someone to stitch the fabrics to cover their planes, but the newspaper which published the advert assumed a misspelling and changed the vowel. Ida Holdgreve is who they took on.[9] When the company closed in 1915 she went on to work as forewoman overseeing many other women sewers at the Dayton-Wright Airplane Company.[10]

Celebrity

Soon after Orville's near-fatal accident, Wilbur asked Katharine to sail to France with their recuperating brother. She and Orville joined Wilbur in Pau in early 1909. Katharine dominated the social scene in Europe, being far more outgoing and charming than her notoriously shy brothers. She put her proficiency in French to use in liaising with European royalty and influential dignitaries like Alfonso XIII, King of Spain, Georges Clémenceau, Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe, and Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia. She also made three flights with Wilbur while they were in Pau, becoming one of the first women to go up in an airplane.[11]

French journalists were captivated by what they saw as the human side of the Wright Brothers. They even concocted a story—which Katharine would take pains to refute in later years—that the “Wright sister” had assisted Wilbur and Orville with their mathematical computations.[13] In recognition of Katharine's vital importance to the Wright family team, the French government honored her as an Officier de l’Instruction Publique –one of France's highest academic distinctions—when her brothers received the prestigious Légion d’Honneur in 1909.[14]

The three Wrights returned to the United States as national heroes and international celebrities. Back home in Dayton, Katharine took on formal business responsibilities, serving briefly on the board of the Wright Company before Orville sold the family airplane business in 1915.[6] At the same time, she became an outspoken supporter of the woman suffrage movement in Ohio. In anticipation of an unsuccessful attempt to amend the state constitution, she marched in a suffrage parade in Dayton on October 24, 1914, along with her octogenarian father and brothers Orville and Lorin.[15] A pioneering feminist, Katharine would later write: “I get all ‘het up’ over living forever in a ‘man’s world,’ with so much discussion about what kind of women men like and so little concern over what kind of men women like, that it's a good deal like the particular subject of woman suffrage used to be with me. Orv always teased me about that. When we were working for it, he used to say that woman suffrage was like Rome, in one respect: all roads led to it, with me.”[16] Katharine traveled to Columbus to lobby state legislators on behalf of woman suffrage, an effort that ultimately bore fruit in 1919, when Ohio became the fifth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

Life after the deaths of Wilbur and Bishop Milton Wright

In 1914, some two years after Wilbur’s premature death, Katharine, Orville, and Bishop Milton Wright moved to Hawthorn Hill, a newly constructed mansion in the Dayton suburb of Oakwood. Bishop Wright died three years later. Carrie Kayler and her husband, Charles Grumbach, also had an apartment in the house. As his scientific career wound down, Orville became increasingly dependent on Katharine. While continuing to manage the household, she looked after his social schedule, correspondence, and business engagements along with his salaried secretary, Mabel Beck.[17] She also played an active behind-the-scenes role in Orville’s decades-long struggle with the Smithsonian Institution to gain appropriate recognition for the Wright Brothers’ invention.[13]

As Orville's consort, Katharine attended many formal ceremonies and aviation events, such the International Air Races in St. Louis in 1923 and Dayton in 1924. In September 1922, they helped the Wright Aeronautical Company christen the Wilbur Wright flying boat, designed by aviation pioneer Grover Loening, and participated in its maiden flight over the Hudson River. At the launch, Katharine and Orville were photographed standing beside Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson, whose professional relationship with the youngest Wright brother led to a brief but intense emotional entanglement with Katharine in the early 1920s, as documented in their extensive correspondence.[18] Prominent in Dayton society, Katharine was an active member of the Helen Hunt Club, a women's literary group; president of the Young Women's League; and a supporter of other civic organizations.[15] She was also the moving force behind the Oberlin Alumni Association in Dayton and served as her class secretary for many years. In 1923, she was elected to the Oberlin College board of trustees and served her alma mater in that capacity from 1924 until her death in 1929. As only the third female trustee in Oberlin's history,[19] she exerted a strong influence in areas such as faculty and presidential appointments, building plans, and academic freedom.[20]

Marriage, later life, and death

Over the years Katharine stayed in touch with newspaperman Henry (Harry) J. Haskell, a close friend from her college days who had once tutored her in math. Associate editor (later editor) of the Kansas City Star, Haskell lived in Kansas City, Missouri, where Katharine and Orville visited him on several occasions. (Their older brother Reuchlin and his family also lived in Kansas City.) Haskell was one of a handful of influential journalists who spearheaded the campaign to vindicate the Wright brothers in their dispute with the Smithsonian. After his wife's death in 1923, he and Katharine began a long-distance romance that was conducted primarily through letters. Although her secret fiancé and Orville had long been friends, Katharine was apprehensive about her brother's likely reaction to their marriage. Her fears were borne out when Haskell belatedly broke the news to Orville: the surviving Wright brother was devastated and virtually stopped speaking to his sister.[4][13]

After procrastinating for more than a year, Katharine finally married Harry on November 20, 1926, in a small private ceremony at the Oberlin home of their mutual friend Professor Louis Lord, a well-known classicist.[21][22] Orville, convinced that his sister had violated a family pact to remain unmarried, refused to attend the wedding and severed all contact with his sister. Other family members were more supportive, however, and one of Katharine's nieces even attended the ceremony with her husband. Leaving Hawthorn Hill in secret and with a heavy heart, Katharine made her new home with Harry in Kansas City. Although they enjoyed a happy marriage, she continued to grieve over her broken relationship with Orville.[13]

In early 1929, as the Haskells were preparing to embark on their belated honeymoon in Europe, Katharine contracted pneumonia. When Orville found out, he still refused to contact her. Their brother Lorin, who had enthusiastically supported Katharine's marriage plans, prevailed on Orville to visit her, and he was at her bedside when she died on March 3, 1929, at age 54.[4]

Legacy

In a posthumous citation, Katharine's fellow Oberlin trustees described her as “a world figure who emerged from and dwelt in a model American home.” In 1931 Haskell donated a fountain to the college in her memory. Featuring a replica of a bronze sculpture by Verrocchio, it stands near the entrance to the Allen Memorial Art Museum, a short distance from the college's Wilbur and Orville Wright Laboratory of Physics.[23]

For decades historians and biographers of the Wright Brothers ignored or downplayed Katharine's role as an integral member of the family team. Only with the surge of interest in women's history in the late twentieth century, and the concomitant discovery of previously unknown letters and other documents, did she come to be recognized as both Wilbur and Orville's unsung partner and a significant figure in the women's movement.

Richard Maurer's The Wright Sister and Ian Mackersey's The Wright Brothers, both published to coincide with the centenary of the first flight in 2003, and David McCullough's The Wright Brothers (2015) reflect the ongoing effort to restore Katharine Wright Haskell to her rightful place in the Wright brothers’ saga. In 2017, Henry J. Haskell's grandson published Maiden Flight, a work of creative nonfiction about her late-life marriage, followed by a three-part biographical podcast titled In Her Own Wright. Novelist Patty Dann adopted a less rigorously source-based approach in The Wright Sister (2020). Dramatic treatments of Katharine's life range from one-woman shows to the 2022 opera Finding Wright by composer Laura Kaminsky and librettist Andrea Fellows Fineberg.[24] In 2022 the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum unveiled a new Wright Brothers exhibit in which Katharine's role is highlighted.[25]

References

- Appleton (1890-01-01). "Portrait of Katharine Wright". Wright Brothers Photographs.

- Dayton, Mailing Address: 16 South Williams Street; Us, OH 45402 Phone: 937 225-7705 Contact. "Katharine Wright's Life Story – Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- "The Wright Brothers | Katharine Wright". airandspace.si.edu. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- Maurer, Richard (2003). The Wright Sister: Katharine Wright and Her Famous Brothers (1st ed.). Brookfield, Conn.: Roaring Brook Press. ISBN 0-7613-1546-2. OCLC 50859278.

- Harry Haskell (2022). In Her Own Wright (three-part podcast about Katharine Wright Haskell).

- Roach, Edward J. (2014). The Wright Company : from invention to industry. Athens. ISBN 978-0-8214-4474-0. OCLC 868579991.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Forever and Always Wright". www2.oberlin.edu. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- McCullough, David G. (2015). The Wright Brothers. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-2874-2. OCLC 897424190.

- Levins, Sandy (2021-05-19). "Ida Holdgreve: Wright Brothers' Plane Seamstress". WednesdaysWomen. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- DeLuca, Leo (March 15, 2021). "How Ida Holdgreve's Stitches Helped the Wright Brothers Get Off the Ground". Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- Crouch, Tom D. (1989). The Bishop's Boys: A Life of Wilbur and Orville Wright. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02660-3. OCLC 18135130.

- "Katharine Wright's first time flying". Wright Brothers Photographs. 1909-02-15.

- Mackersey, Ian (2003). The Wright Brothers: The Remarkable Story of the Aviation Pioneers Who Changed the World. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-86144-8. OCLC 52695003.

- "PART 6: AWARDS AND CERTIFICATES, 1909–1947 | Wright State University". wright.libraryhost.com. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- Derringer, Sherri Lynn (2007). “Women's Campaign for Culture: Women's Clubs and the Formation of Women's Institutions in Dayton, Ohio, 1883–1933” (dissertation, Wright State University).

- Katharine Wright to Henry J. Haskell, November 11, 1924, Katharine Wright Haskell Papers, Wright State University Libraries.

- "WRIGHT BROTHERS – BECK, Mabel (1890–1959) Archive of correspondence and typescripts including two autograph letters signed and ten typed letters signed ("Mabel Beck" and "B"), [Dayton] to Earl Findley, 28 June 1950 to 7 April 1956. – Typescript, "The First Airplane – After 1903" – Draft typescript of the former article with holograph annotations and autograph note signed ("Mabel Beck") at conclusion, [Dayton] 289 November 1954 – GARDNER, Lester. Autograph letter signed ("Lester") to Earl Findley, [New York], 28 July 1951 [With:] Orville and Wilbur WRIGHT, "The Wright Brothers' Aëroplane", offprint from The Century Magazine September, 1908 – Period photographs of the Wrights with handwritten annotations by Beck on versos – copies of outgoing correspondence, pamphlets, postcards, and related material". www.christies.com. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- Vilhjalmur Stefansson and Eleanor Stefansson Nef Papers, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- "Guide to the Women's History Sources in the Oberlin College Archives." Pamela Kirwin Adams, Alexandra Weil, and Roland M. Baumann, compilers. Roland M. Baumann, editor. Oberlin College Archives, Oberlin, Ohio.

- oberlincollegelibraries. "#WCW: Katharine Wright Haskell". Oberlin College Libraries. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- Times, Special to The New York (1926-11-21). "KATHERINE WRIGHT WED TO H.J. HASKELL, EDITOR; Sister of Airplane Inventors Bride of Executive of The Kansas City Star". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- "Katharine Wright". www.wright-brothers.org. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- Gabe, Catherine (Summer 2007). "Historic Fountain Fixed the Wright Way". Oberlin Alumni Magazine. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- Law, Joe (May 2022). "Finding Wright". Opera News. 86 (11).

- Magazine, Smithsonian; Ault, Alicia. "After the Wright Brothers Took Flight, They Built the World's First Military Airplane". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

Further reading

- Howard, Fred (1987). Wilbur and Orville: A Biography of the Wright Brothers. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-54269-X.

- Crouch, Tom D. (1989). The Bishop’s Boys: A Life of Wilbur and Orville Wright. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-30695-8.

- Maurer, Richard (2003). The Wright Sister: Katharine Wright and Her Famous Brothers (1st ed.). Roaring Brook Press. ISBN 0-7613-1546-2.

- Mackersey, Ian (2003). The Wright Brothers: The Remarkable Story of the Aviation Pioneers Who Changed the World. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-86144-1.

- McCullough, David (2015). The Wright Brothers. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-2874-2.

- Haskell, Harry (2017). Maiden Flight. Academy Chicago. ISBN 978-1-61373-637-1.

- Dann, Patty (2020). The Wright Sister. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-299311-3.

External links

- Digital scans of Katharine Wright Haskell’s letters in the Wilbur and Orville Wright Papers at the Library of Congress

- I n Her Own Wright: three-part podcast about Katharine Wright Haskell, sponsored by the National Park Service and public radio station 91.3 WYSO (Yellow Springs, Ohio)

- Public Radio interview with historian Cindy Wilkey about Katharine's role in the Wright Brothers' success

- Biographical essay at Wright Brothers Airplane Company: A Virtual Museum of Pioneer Aviation

- Biographical essay by Dr. Richard Stimson

- Interview with the screenwriter of an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Sundance Institute-supported script about Katharine Wright