Kazimieras Jaunius

Kazimieras Jaunius (1848–1908) was a Lithuanian Catholic priest and linguist. While Jaunius published very little, his major achievements include a well regarded Lithuanian grammar, systematization and classification of the Lithuanian dialects, and descriptions of Lithuanian accentuation. Though most of his conclusions on etymology and comparative linguistics were proven to be incorrect, his works remain valuable for vast observational data.

Kazimieras Jaunius | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 19 May 1848 |

| Died | 9 March 1908 (aged 59) |

| Burial place | Petrašiūnai Cemetery (reburied) |

| Nationality | Lithuanian |

| Alma mater | Kaunas Priest Seminary Saint Petersburg Roman Catholic Theological Academy |

| Occupation(s) | Catholic priest, linguist |

Jaunius studied at the Kaunas Priest Seminary and Saint Petersburg Roman Catholic Theological Academy. He was ordained a priest in 1875 and earned his Master of Theology in 1879. He taught several subjects, including moral theology and homiletics, at the Kaunas Priest Seminary from 1880 to 1892. His class notes on the Lithuanian language became a well regarded Lithuanian grammar book first published in 1897. After disagreements with Bishop Mečislovas Leonardas Paliulionis, Jaunius became a dean in Kazan in 1893. However, he experienced severe mental health issues and returned to Lithuania to recuperate in 1895. He obtained a teaching position at the Saint Petersburg Roman Catholic Theological Academy in 1898. He was of poor health and developed graphophobia (fear of writing). In 1902, Kazimieras Būga was hired as Jaunius' personal secretary to help collect and publish Jaunius' work. Jaunius retired from teaching in 1906 and died in 1908. Būga published two of his major works already after Jaunius' death.

Biography

Early life and education

Jaunius was eldest of five children born to a family of Lithuanian peasants in the village of Lembas near Kvėdarna. His parents worked about 60 dessiatins of land.[2] His father was illiterate, but he decided to send Jaunius to school. He attended a primary school in Rietavas, progymnasium in Telšiai in 1860–1864, and gymnasium in Kaunas (former Kražiai College) in 1866–1869. He did not complete the gymnasium education and withdrew in 1869 but continued to study the languages translating various texts from Latin, German, Polish. In November 1871, he enrolled into the Kaunas Priest Seminary where he became a student of Antanas Baranauskas who taught homiletics in Lithuanian and studied the different dialects of the Lithuanian language. Baranauskas asked students to write down samples of local dialects and Jaunius turned in a tale in the dialect of Endriejavas residents. This tale was published by Czech linguist Leopold Geitler in 1875. Baranauskas mentored Jaunius and introduced him to other linguists, including Jan Niecisław Baudouin de Courtenay, Jan Aleksander Karłowicz, Hugo Weber. As a gifted student, Jaunius was sent to the Saint Petersburg Roman Catholic Theological Academy even prior the completion of the priest seminary, but he failed exams in Russian language, geography, and history. He graduated from the seminary in June 1875 and was ordained a priest. He then successfully retook exams for the Theological Academy and continued to study theology. Several noted linguists and philologists, including Lucian Müller, Franz Anton Schiefner, Daniel Chwolson, and Nikolai Petrovich Nekrasov, taught at the academy. By the time he graduated from the academy, he knew eight languages (Lithuanian, Russian, Polish, Latin, Ancient Greek, Sanskrit, German, French). In 1879, the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences asked Jaunius to review a collection of Lithuanian folk songs compiled by Antanas Juška. After defending two thesis (one on morals in comedies of Nikolai Gogol and another on theology De conservatione mundi per Deum), he was awarded the Master of Theology in summer 1879.

Teacher in Kaunas and illness

After the graduation, Jaunius was offered a teaching position at the academy in Saint Petersburg, but Bishop Mečislovas Leonardas Paliulionis did not approve it and appointed Jaunius as vicar of Kaunas Cathedral in December 1879. In September 1880, he became teacher of Latin, catechism, and moral theology at the Kaunas Priest Seminary. In September 1883, he became secretary of Bishop Paliulionis and had to leave the seminary. Jaunius returned to the priest seminary in October 1885 as teacher of moral theology, homiletics, and Lithuanian language.[13] He was a popular professor and his Lithuanian lectures inspired several priests, including Juozas Tumas-Vaižgantas and Maironis, to join the Lithuanian National Revival.[15] His lectures were often impulsive and disorganized; for example, he would often catch a word from a student and start analyzing its etymology. Therefore, his students often did not finish the full grammar in two years.[15] Jaunius devoted his time to linguistic studies and published several articles on the dialects of the Lithuanian language.

In 1892, Bishop Paliulionis dismissed Jaunius from the priest seminary because he was not following the strict rules of the seminary. As he was no longer welcome in the Diocese of Samogitia, Jaunius searched for another posting and considered Dorpat (Tartu).[18] He finally found a vacant deanery in Kazan in March 1893. Jaunius possibly targeted Kazan because it had a university where Alexander Alexandrov, who had written on the Lithuanian language, was a professor. However, the ordeal with the bishop negatively affected Jaunius' mental health. He was plagued by homesickness and loneliness and suffered from hallucinations and paranoia. When he could not hold a mournful mass for Tsar Alexander III of Russia due to his poor health, Tsarist authorities suspected political motives and wanted to exile him to Siberia. Instead, they put him in a psychiatric hospital. In 1895, Jadvyga Juškytė brought Jaunius back from Kazan to Lithuania where he lived with friends and acquaintances trying to improve his health and recover, but had no means of earning a living. He petitioned the Governor of Kaunas for a monthly disability pay and was hoping to get a teaching job at the Saint Petersburg Roman Catholic Theological Academy. He frequently visited Saint Petersburg where he reestablished academic contacts. He helped Eduards Volters with the publication of the postil of Mikalojus Daukša and delivered three lectures on Lithuanian word endings to the Neo-Philological Society in 1898.

Professor in Saint Petersburg

In December 1898, Jaunius finally managed to get a teaching position at the Theological Academy. Initially, he taught Ancient Greek for an annual salary of 400 rubles but at the start of the 1899/1900 school year, he was promoted to a professor of Latin and Ancient Greek with a salary of 1,000 rubles. In 1902, he transitioned to teaching Biblical Hebrew. He was also active in philological societies and continued his linguistic research. In 1903, the Jagiellonian University in Kraków offered him chairmanship of the newly formed Lithuanian language section but Jaunius refused possibly due his deteriorating health – he complained of poor eyesight, weak heart, pain in legs, auditory issues, etc. He spent considerable amount of time searching for treatments and visiting sanatoriums abroad. Towards the end of his life, he also developed graphophobia (fear of writing). When Jonas Basanavičius asked him why he made so many notes in book margins instead of writing them down in a notebook, Jaunius replied that he was afraid of white paper and almost never used blank sheets. Therefore, he avoided writing down his thoughts or publishing his research. Afraid that his knowledge was wasting, professors Filipp Fortunatov and Aleksey Shakhmatov organized funding for a private secretary. Kazimieras Būga, then a gymnasium student, was hired in 1902 and became a student of Jaunius.

Jaunius' reputation as an expert on the Lithuanian language grew.[31] In late 1903, Vyacheslav von Plehve, Minister of the Interior, asked Jaunius' expert opinion on whether the Cyrillic script was suited for the Lithuanian language (publication of Lithuanian texts in the Latin alphabet was banned since 1864). According to memoirs of Pranciškus Būčys, Jaunius delayed his response and insisted on correcting, rewriting, and reediting the response multiple times – Būčys had to rewrite the letter several times and mail it out before Jaunius could point out any further corrections.[18] His reply that the Lithuanian language used a Latin–Lithuanian alphabet (and not Latin–Polish) was added the case file during government debates that led to the lifting of the ban in early 1904.[33] In 1904, Jaunius received an honorary doctorate in comparative linguistics from the Kazan University (that year the university celebrated its 100th anniversary). In 1907, he was one of the founding members of the Lithuanian Scientific Society and was elected its honorary member.

Jaunius health forced him to resign from the Theological Academy in spring 1906. He received a monthly pension of 50 rubles and continued to live in Saint Petersburg. For a year, he lived in a room at the Theological Academy and then rented a cramped one-room apartment in the city. He died of a heart attack in March 1908 alone and in poverty. Jan Niecisław Baudouin de Courtenay and Alexander Alexandrov wrote articles about Jaunius' life that were published as separate booklets. His body was transported and buried in Kaunas. Lithuanian magazines Draugija and Viltis devoted entire issues to his memory. Lithuanian activists started a fundraising campaign to erect a monument (built in 1913 by sculptor Antanas Aleksandravičius) and to publish his works. In 1991, a granary was reconstructed at the birthplace of Jaunius and turned into his memorial museum.[2]

Works

Jaunius published very little. His two major books were published by his secretary Kazimieras Būga already after his death. Most of Jaunius research was focused on etymology.[31] Jan Niecisław Baudouin de Courtenay praised Jaunius' deep knowledge of multiple languages and his ability to take in this vast information, systematize it, and arrive to broad conclusions. His conclusions were often incorrect which some attribute to his lack of specialized linguistic education.

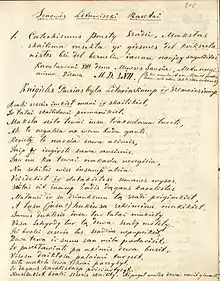

Lithuanian grammar

His major work, the Lithuanian grammar, was based on his teaching notes from the Kaunas Priest Seminary. At the time, there was no published Lithuanian grammar that Jaunius could have used. His students copied and recopied his notes which circulated widely. They were first published (hectographed) by a group of Lithuanian students without Jaunius' knowledge or input in Dorpat (Tartu) in 1897. It was a 338-page work in four parts: spelling, phonetics, case inflection, and verb conjugation. In 1905, professor Filipp Fortunatov agreed to finance a proper publication of the grammar. However, Jaunius managed to review and correct only 48 pages of the manuscript. Therefore, Būga finished preparing the grammar based on the hectographed copy from 1897. The final 216-page book was published in 1911. Būga further worked on preparing a Russian translation which was published in 1916.

While the grammar was written as a practical textbook for Lithuanian clerics, it contained new and deep insights into the living language and was praised by Jonas Jablonskis for its wealth of knowledge. Jablonskis used Jaunius' grammar extensively when preparing his own publication that became the key work in creating the standard Lithuanian language.[18] Nevertheless, its coverage was inconsistent and not comprehensive. For example, verbs were analyzed in 80 pages while syntax only briefly described in 10 pages. Jaunius did not prioritize one Lithuanian dialect over another and did not attempt to standardize pronunciation of the different dialects. Instead, he attempted to modify spelling to accommodate different pronunciation. Therefore, he introduced ten new letters that each dialect could pronounce based on its needs. That made the spelling cumbersome and impractical and it was not adopted by anyone else. Jaunius provided examples from different dialects and thus developed a more comprehensive picture of the Lithuanian language and its most common features. In his work, Jaunius had to develop Lithuanian terminology for various linguistic terms. He was not very successful in this area as he often used awkward compound words or simply translated Latin terms without fully adapting them to the Lithuanian language. Nevertheless, some of his terms were adopted and are widely used, including linksnis for grammatical case, veiksmažodis for verb, priesaga for suffix, etc.

Dialectology

Jaunius studied Lithuanian dialects and grouped them into sub-dialects. His classification was later improved by Antanas Salys.[49] Their classification is known as Jaunius–Salys or traditional classification when compared to the newer classification of Zigmas Zinkevičius and Aleksas Girdenis. In 1891–1898, he wrote and published descriptions of dialects in six uyezds – Ukmergė in 1890, Kaunas in 1891, Raseiniai in 1892, Zarasai in 1894, Šiauliai in 1895, Panevėžys in 1897 and 1898. In 1900, he also published an article on Lithuanian pitch-accent in 1900. All of these articles were written in Russian and published in an annual publication Memorial Book of the Kovno Governorate (Памятная книжка Ковенской губернии), the yearbook of the Kaunas government. Jaunius wrote about the dialect classification in his Lithuanian grammar book. Jaunius identified the two major dialects – Samogitian and Aukštaitian – based on pronunciation of certain sounds. He then subdivided each dialect into three sub-dialects – Samogitians based on the pronunciation of diphthongs ie and uo and Aukštaitians based on diphthongs am, an, em, en and letter l before ė. Jaunius did not separate out the Dzūkian dialect. While he was not always consistent in his classification, he clearly identified the criteria for separating local variations into sub-dialects. His observations and rules for accents remain relevant and authoritative.[54]

Other works

Būga wrote down 3,043 pages in six volumes of Jaunius' teachings on Lithuanian, Latvian, and Prussian languages and their Baltic proto-language. Since Jaunius could not work on getting them published, Būga wrote and prepared the first volume of Aistiški studijai (Baltic Studies) for publication in May 1906, but after delays it was published only in May 1908. Būga also had the second volume prepared in 1906–1907, but after his own linguistic studies Būga realized that many of Jaunius' theories were incorrect and amateurish. For example, when explaining etymology of a certain word, Jaunius often searched for equivalents in the trendy Greek or Armenian languages instead of closer neighbors. He often grouped semantically similar but phonetically different words and attempted to find their true original form.[49] While the conclusions are often incorrect, the notes are still valuable for their observational data.[58]

Jaunius studied the relationship between Indo-European languages and Finno-Ugric languages or Semitic.[49] He left notes for Lithuanian–Estonian (446 words) and Lithuanian–Finnish (474 words) etymological dictionaries. He also prepared a dictionary of loanwords of Baltic origin in the Finnish language (222 words). He likely became interested in Finno-Ugric languages after reading a work of August Ahlqvist in 1878.[60] He claimed to have discovered equivalents of consonants in Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Semitic languages. In his last decade, Jaunius was interested in many different topics and started many projects, but was unable to finish them. A collection of his previously unpublished manuscripts was published in 1972.

References

- In-line

- Šilalės Vlado Statkevičiaus muziejus 2015.

- Grickevičius 2016, p. 82.

- Grickevičius 2016, p. 91.

- Barzdukas 1948.

- Skardžius 1972, p. 514.

- Merkys 1994, p. 380.

- Sabaliauskas 2005.

- Girdenis 2003, p. 25.

- Skardžius 1972, p. 515.

- Skrodenis 1985, p. 86.

- Bibliography

- Barzdukas, Stasys (May 1948). "Kazimieras Jaunius". Aidai (in Lithuanian). ISSN 0002-208X.

- Drotvinas, Vincentas; Grinaveckis, Vladas (1970). Kalbininkas Kazimieras Jaunius (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Mintis. OCLC 923587763.

- Girdenis, Aleksas (2003). "Kazimieras Jaunius – dialektologas" (PDF). Kazimieras Jaunius (1848-1908): tarmėtyrininkas ir kalbos istorikas: konferencijos pranešimų tezės (in Lithuanian). Lietuvių kalbos institutas.

- Grinaveckis, Vladas (1973). "Kalbininko Kazimiero Jauniaus rankraštinis palikimas". Baltistica (in Lithuanian). 9 (1). doi:10.15388/baltistica.9.1.1817. ISSN 2345-0045.

- Grickevičius, Artūras (2016). Katalikų kunigų seminarija Kaune: 150-ies metų istorijos bruožai (in Lithuanian). Versus aureus. ISBN 9786094671999.

- Merkys, Vytautas (1994). Knygnešių laikai 1864–1904 (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Valstybinis leidybos centras. ISBN 9986-09-018-0.

- Sabaliauskas, Algirdas (2005-08-17). "Kazimieras Jaunius". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras.

- Šilalės Vlado Statkevičiaus muziejus (2015). "Apie klėtelę-muziejų" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Skardžius, Pranas (1972). "Jaunius, Kazimieras". In Sužiedėlis, Simas (ed.). Encyclopedia Lituanica. Vol. II. Boston, Massachusetts: Juozas Kapočius. OCLC 883965704.

- Skrodenis, Stasys (1985). "Nauja apie Kazimierą Jaunių". Baltistica (in Lithuanian). 21 (1). doi:10.15388/baltistica.21.1.67. ISSN 2345-0045.