Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu

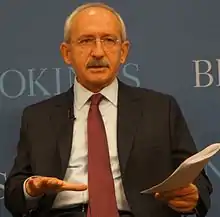

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu (Turkish: pronounced [keˈmal kɯˌɫɯtʃ.daˈɾoːɫu] ⓘ; also referred to by his initials KK; born 17 December 1948)[10] is a Turkish politician and the leader of the Republican People's Party (CHP). He has been Leader of the Main Opposition in Turkey since 2010. He served as a member of parliament for Istanbul's second electoral district from 2002 to 2015 and as an MP for İzmir's second electoral district as of 7 June 2015.

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) Kılıçdaroğlu in 2023 | |

| Leader of the Main Opposition | |

| Assumed office 22 May 2010 | |

| President | Abdullah Gül Recep Tayyip Erdoğan |

| Prime Minister | Recep Tayyip Erdoğan Ahmet Davutoğlu Binali Yıldırım |

| Preceded by | Deniz Baykal |

| Leader of the Republican People's Party | |

| Assumed office 22 May 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Deniz Baykal |

| Vice President of the Socialist International | |

| In office 21 August 2012 – 13 December 2014 | |

| President | George Papandreou |

| Country | Turkey |

| Preceded by | Deniz Baykal |

| Succeeded by | Umut Oran |

| Member of the Grand National Assembly | |

| In office 18 November 2002 – 14 May 2023 | |

| Constituency | İstanbul (II) (2002, 2007, 2011) İzmir (II) (Jun 2015, Nov 2015, 2018) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Kemal Karabulut[1] 17 December 1948 Ballıca, Nazımiye, Tunceli, Turkey[2] |

| Political party | Republican People's Party (after 1999) |

| Other political affiliations | Democratic Left Party[3] (until 1999) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Residence | Ankara |

| Alma mater | Ankara Academy of Economics and Commercial Sciences[4] (Gazi University) |

| Occupation |

|

| Profession | Civil servant |

| Signature |  |

| Nickname(s) | Gandhi Kemal[5] Grey wolf Kemal[6] Democratic uncle of the youth[7] Piro[8] Mr. Kemal[9] |

Before entering politics, Kılıçdaroğlu was a civil servant and served as the director-general of the Social Insurance Institution from 1992 to 1996 and again from 1997 to 1999. He was elected to Parliament in the 2002 general election and became the CHP's parliamentary group leader. In the 2009 local elections, he was nominated as the CHP candidate to run for Mayor of İstanbul, but lost to the AKP. He was elected deputy chairman of the Socialist International in August 2012. After Deniz Baykal resigned as the party's leader in 2010, Kılıçdaroğlu announced his candidacy and was unanimously elected as the leader of the CHP. He was seen as likely to modernize the CHP. Although the CHP saw a subsequent increase in its share of the vote, it was unable to unseat the ruling AKP as of 2023. As leader of the main opposition, Kılıçdaroğlu's strategy has been to construct big-tent coalitions with other parties, which culminated in the formation of the Nation Alliance and CHP's subsequent victories in the 2019 local elections. He was the CHP's and the Nation Alliance's joint candidate for the 2023 Turkish presidential election, but lost to incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Early life

Kemal Karabulut was born on 17 December 1948 in the Ballıca village of Nazımiye district in Tunceli Province, eastern Turkey,[11] to Kamer, a clerk-recorder of deeds and his wife Yemuş. Kemal was the fourth oldest of their seven children.[12]

Kemal's father changed the family name from Karabulut to Kılıçdaroğlu in the 1960s because everyone in their village had the same last name (Karabulut). His father was among thousands of exiled Alevis following the failed Dersim rebellion.[13]

Kemal continued his primary and secondary education in various places such as Erciş, Tunceli, Genç, and Elazığ. He studied economics at the Ankara Academy of Economics and Commercial Sciences, now Gazi University, from which he graduated in 1971. During his youth, he earned his living by selling goods.[12]

Professional career

After university, Kılıçdaroğlu entered the Ministry of Finance as a junior account specialist in 1971. He was later promoted to accountant and was sent to France for additional professional training. In 1983, he was appointed deputy director general of the Revenues Department in the same ministry. At that time he worked closely with Prime Minister Turgut Özal. In 1991, Kılıçdaroğlu became director-general of the Social Security Organization for Artisans and Self-Employed (Bağ-Kur). In 1992 he was appointed director-general of the Social Insurance Institution (Turkish: Sosyal Sigortalar Kurumu, abbreviated SSK).[12][14]

In 1994, Kılıçdaroğlu was named "Civil Servant of the Year" by the weekly periodical Ekonomik Trend.[12]

Kılıçdaroğlu retired from the Social Insurance Institution in January 1999. He taught at Hacettepe University and chaired the Specialized Commission on the Informal Economy within the framework of the preparation of the Eighth Five-Year Development Plan. He also acted as a member of the Executive Board of İşbank.[15]

Early political career

Member of Parliament

Kılıçdaroğlu retired from civil service in 1999 and tried to enter politics from within Bülent Ecevit's Democratic Left Party (DSP). He was often referred to as the "star of the DSP".[3] It was claimed that he would be a DSP candidate in the upcoming 1999 general election, in which the DSP came first.[16] However, he did not succeed in this venture as he could not get on the party's candidates' list. Instead, during his chairmanship of an association that aimed to protect citizen tax payments, he was invited by the leader of the CHP Deniz Baykal to join his party and accepted the invitation.[12]

Following the 2002 general election, he entered the parliament as a deputy from Istanbul. In the 2007 general election, he was re-elected to parliament. He became deputy speaker of his party's parliamentary group.[12]

Kılıçdaroğlu's efforts to uncover malpractice among high-ranking Justice and Development Party (AKP) politicians carried him to headlines in the Turkish media. Two deputy chairmen of the ruling AKP, Şaban Dişli and Dengir Mir Mehmet Fırat, resigned from their respective positions in the party following television debates with Kılıçdaroğlu. He publicly accused the AKP-affiliated Mayor of Ankara, Melih Gökçek, of complicity in a corruption scandal relating to the "Deniz Feneri" charity based in Germany.[12]

2009 İstanbul mayoral candidate

Kılıçdaroğlu was announced as the CHP's mayoral candidate for the 2009 local elections by the party leader Deniz Baykal in January 2009. Kılıçdaroğlu announced that he would run his campaign based on clean politics, vowing to open cases of corruption against the serving incumbent, AKP mayor Kadir Topbaş. Claiming that he would work for the workers of İstanbul, he challenged Topbaş to a televised live debate.[17] Kılıçdaroğlu lost the election with 37% of the votes against Topbaş's 44.7%.

Election to the CHP leadership

Long-time leader of the CHP, Deniz Baykal resigned on 10 May 2010 following a video tape scandal. Kılıçdaroğlu announced his candidacy for the position on 17 May, five days before an upcoming party convention. According to reports, the party was divided over the leadership issue, with its Central Executive Board insisting that Baykal retake the position.[18] After Kılıçdaroğlu received the support of 77 of his party's 81 provincial chairpersons,[19] Baykal decided not to run for re-election.[20]

For a candidacy to become official, CHP by-laws require the support of 20% of convention delegates.[21] At the party convention, in May 2010, Kılıçdaroğlu's candidacy received the signatures of 1,246 out of the 1,250 delegates, which set a new record for the CHP.[22]

In view of this overwhelming support, the presidium of the party convention decided to move the election, initially scheduled for Sunday, forward to Saturday. As expected, Kılıçdaroğlu was elected unanimously as party chairman with 1,189 votes, not counting eight votes that were found to be invalid.[23][24]

Leader of the opposition

Kılıçdaroğlu took office as the Leader of the Main Opposition on 22 May 2010 by virtue of leading the second largest political party in the Grand National Assembly. Many media commentators and speculators predicted that Kılıçdaroğlu would breathe new life into the CHP, after consecutive election defeats under Baykal's leadership.[25]

2010 constitutional referendum

Kılıçdaroğlu's first campaign as the CHP leader was the constitutional referendum held on 12 September 2010. Although the initial voting process in Parliament that would determine the proposals that were voted on in the referendum had begun under Baykal's leadership, Kılıçdaroğlu employed a tactic of boycotting the parliamentary process. The governing AKP, which had submitted the proposals, held 336 seats. Since a constitutional reform proposal required 330 votes to be sent to a referendum, the parliamentary approval of all of the government's constitutional reforms was mathematically possible regardless of how the CHP voted. The AKP's proposed constitutional reforms, which included changes to the Turkish Judiciary, were sent for approval in a referendum on 12 September 2010.

Kılıçdaroğlu not only campaigned for a 'no' vote against the proposals, but also sent the Parliamentary voting process to court over alleged technical irregularities. The CHP subsequently sent the proposals to court over alleged violations of the separation of powers in the proposed changes. The Constitutional Court eventually ruled against the CHP. Kılıçdaroğlu, along with members of minor opposition parties, argued that the proposed changes were an attempt to politicise the judiciary and further increase the control of the AKP over neutral state institutions. The referendum proposals were accepted by 57.9% of voters, with 42.1% voting against.[26]

2011 general election

The 2011 general election was the first general election in which Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu participated as the leader of Republican People's Party (CHP). The former CHP leader Deniz Baykal resigned from his post in May 2010 and left the CHP with 26% of the votes, according to opinion polls. Kılıçdaroğlu announced that he would resign from his post if he was not successful in the 2011 elections. He did not provide details as to what his criteria for success were.[27]

Over 3,500 people applied to run for the main opposition party in the June elections. Male candidates paid 3,000 Turkish Liras to submit an application; female candidates paid 2,000 while those with disabilities paid 500 liras.[28] Among the candidates were former CHP leader Deniz Baykal and arrested Ergenekon suspects such as Mustafa Balbay and Mehmet Haberal.[29]

The party held primary elections in 29 provinces. Making a clean break with the past, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu left his mark on the Republican People's Party's 435-candidate list, leaving off 78 current deputies as he sought to redefine and reposition the main opposition. The CHP's candidate list also included 11 politicians who were formerly part of center-right parties, such as the Motherland Party, the True Path Party and the Turkey Party.[30]

Center-right voters gravitated toward the AKP when these other parties virtually collapsed after the 2002 elections. Key party figures that did not make it on to the list, criticised the CHP for making "a shift in axis".[31] His statement on the election results "CHP is the only party that increased the number of deputies in the election. In a short period of 6 months, CHP gained 3.5 million new voters. So we will not demoralise ourselves," he said.[32]

2015 general elections

The June 2015 general election was the second general election which Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu participated as the leader of CHP. The party won 11.5 million votes (24.95%) and finished with 132 elected Members of Parliament, a decrease of 3 since the 2011 general election. The decrease of 1.03% compared to their 2011 result (25.98%) was attributed to CHP voters voting tactically for the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) to ensure that they surpassed the 10% election threshold. While the result demonstrated a stagnant CHP vote, HDP's entry into parliament resulted in AKP losing its parliamentary majority.

Weeks of coalition talks between AKP and CHP and a possible Kılıçdaroğlu premiership proved ultimately fruitless. Kılıçdaroğlu then tried to form a government with MHP and HDP, offering MHP's chairman Devlet Bahçeli the premiership, but ideological differences between the nationalists and the Kurds were too large, and Bahçeli announced that he wanted to be the main opposition anyway. A snap election was called for November, in which AKP regained its majority. No opinion poll, apart from one dubious poll released in March 2014, showed the CHP ahead of the AKP between 2011 and 2015.

2016 coup attempt

Kılıçdaroğlu supported the government in the 2016 coup d'etat attempt and condemned the putchists.[33]

A couple months later his convoy was attacked in Artvin by the PKK.[33][34]

Constitutional referendum

After the 2017 Turkish constitutional referendum, which significantly expanded President Erdoğan's powers, Kılıçdaroğlu and CHP filed a court appeal against a decision by Turkey's Supreme Electoral Council (YSK) to accept unstamped ballots. Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu has said that the YSK decision may be appealed to the ECHR, but members of the AKP government have said that neither ECHR nor Turkey's Constitutional Court have any jurisdiction over the YSK decision. Kılıçdaroğlu said: "In 2014 [the Constitutional Court] said 'Elections are canceled if there is no seal on ballot papers or envelopes.'[ ... ]The YSK can't express an opinion above the will of the parliament,[ ... ]If the Constitutional Court rejects our application, we will regard the changes as illegitimate. There is also the ECHR. If necessary, we will take the case there."[35][36]

In 2017, ahead of the referendum, Kılıçdaroğlu flashed the greywolf sign, used by nationalists.[37] It has been suggested that this is to compete with the MHP and the AKP for right-wing voters.[38][39]

March for Justice

In June 2017, Enis Berberoğlu, a member of the Turkish parliament from the opposition Republican People's Party (CHP), was sentenced to 25 years in prison for allegedly leaking state secrets to a newspaper. CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu responded by organizing a peaceful, 420-kilometer walk from Ankara to Istanbul, called the "Justice March", to protest what he saw as a lack of justice and democracy in Turkey. The march lasted for 25 days, attracting a diverse range of participants, and ended with a large rally in Maltepe. Along the way, participants faced various challenges, such as attacks with stones and manure being thrown at them.[16][17]

The march was criticized by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, his ruling Justice and Development Party, and the Nationalist Movement Party, but supported by the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party. [14] After the march, two books were published about the event, and the CHP held a "Justice Congress" in Çanakkale in August 2017.[18] It was during this March Kılıçdaroğlu received the nickname Gandhi Kemal.[40]

2018 elections

In the 2018 elections, Kılıçdaroğlu as leader of the CHP and İyi Parti leader Meral Akşener established Nation Alliance (Millet İtifakı) as an electoral alliance in response to the AKP and MHP's People's Alliance (Cumhur İtifakı). Nation Alliance was soon joined by the Felicity Party and Democrat Parties.

2019 municipal election

In 2019, Kılıçdaroğlu and Akşener continued their parties' cooperation in the 2019 municipal election, capturing the mayoralties of Istanbul and Ankara from the AKP after a quarter of a century of control by Islamist parties.

2023 presidential campaign

Kılıçdaroğlu, who has followed a big tent policy for a long time, announced on his social media account and CHP social media accounts on 13 November 2021 that the CHP has made mistakes in the past and has decided to embark on a journey of reconciliation with his "Call for Reconciliation".[41]

Upon Kılıçdaroğlu's call, on 12 February 2022, 6 opposition party leaders (Good Party Chairman Meral Akşener, Future Party Chairman Ahmet Davutoğlu, DEVA Party Chairman Ali Babacan, Felicity Party Chairman Temel Karamollaoğlu) met in Ahlatlıbel, Ankara to discuss a consensus text on a strengthened parliamentary system and an electoral alliance was officially announced, the alliance was called the "Table of Six".

When the issue of a joint candidate was raised by the Table of Six, Kılıçdaroğlu pointed to the Table of Six on FOX TV's morning show "Çalar Saat" on 5 September 2022 and said, "If there is a consensus on me, I am ready to run for the presidential elections." This was the first time Kılıçdaroğlu openly expressed his will to run for the presidential elections.[42][43] Ekrem İmamoğlu, the mayor of Istanbul, and Mansur Yavaş the mayor of Ankara announced their support for Kılıçdaroğlu's candidacy. [44][45] On 6 March 2023, he declared his candidacy for the 2023 Turkish presidential election.[46] His candidacy is supported by the Party of European Socialists.[47][48] He was beaten by incumbent president Erdoğan in the runoff election.[49]

Political positions

Kılıçdaroğlu has been described as a social democrat.[50]

Freedom of speech

In January 2016, he was prosecuted for insulting President Erdoğan for making statements that implied the President is a dictator after Kılıçdaroğlu spoke out against the arrest of over 20 Academics for Peace who signed a petition condemning a military crackdown in the Kurdish-dominated southeast.[51][52] What Kılıçdaroğlu said was: "Academics who express their opinions have been detained one by one on instructions given by a so-called dictator."[51]

Kılıçdaroğlu criticized the European Court of Human Rights for rejecting a petition from a Turkish teacher who applied to the ECHR claiming that he was wrongly dismissed from his position during the 2016-17 Turkish purges. The ECHR said that plaintiffs should apply to Turkey's State of Emergency Investigation Commission before applying to the Court. Kılıçdaroğlu replied: "Don't you know what is going on in Turkey? Which commission are you talking about? People are dying in prisons. We waited five months to just appoint members."[53]

Kurds

During a visit to the headquarters of the pro-Kurdish Peoples Democratic Party (HDP) he emphasized that the place where a solution to the Kurdish question was to be found was the parliament and opposed the closure of the HDP.[54] In relation to the Kurdish language being recognized as an "unknown language" in the minutes of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, he emphasized that Turkey national broadcasts in Kurdish language itself and suggested to revise the practice.[54]

Defence industry

Kılıçdaroğlu said he would continue to support the Turkish drone industry.[55]

Nationalism

On 31 May 2022, in response to Devlet Bahçeli, Kılıçdaroğlu defined himself as nationalist, saying "I am not like Bahçeli, I am a real nationalist, a real idealist.[56] On 6 May 2023, during his rally in Erzincan, Kılıçdaroğlu said:[57]

Our understanding of nationalism is patriotism. Not only that, they sold the tank pallet factory to the Qatari army. I will take that tank pallet factory from the Qatari army and deliver it to our army. Because this factory is yours. One last thing, they say we are nationalists, the story is of course seasonal nationalism. Unlike their children, I sent my son to the army. I didn't pay for his military service. Just as the poor's son went to the army. That's how I sent my son. I want everyone to know that too. You will tell nationalistic stories, you will send your son with money [paid military service], and you will tell nationalistic stories to me. I don't buy it.

NATO

Kılıçdaroğlu is in favor of Turkey's strengthened role in NATO. In an interview with The Wall Street Journal, Kılıçdaroğlu stated, "Turkey is a member of the Western alliance and NATO, and Putin also knows this well. Turkey must comply with decisions taken by NATO."[58]

European Union

Kılıçdaroğlu declared that he will pursue a more Western-oriented policy if he comes to power in the presidential and parliamentary elections. He also conveyed positive messages to the European Union.

During a program at the Johns Hopkins University in Washington, Kılıçdaroğlu said, "The full membership to the EU is a common objective of all six opposition leaders. We are going to implement our democratic reforms without waiting for the EU to open negotiation chapters. We will bring all the democratic rules to our country."[59]

Middle East

Kılıçdaroğlu vowed to establish the "Organization of Peace and Cooperation in the Middle East" with Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey as its member states.[60]

Azerbaijan

Kılıçdaroğlu supported Turkey's support to Azerbaijan and said the country's position is in line with international laws.[61]

I am saying that the foreign policy followed [by Turkey] has always been wrong. But Azerbaijan is in a different position. Because their land is under occupation. Azerbaijan is also being told not to speak up. It rightfully defends its own territory. No matter which state it is, it should support Azerbaijan. It is the most natural right of Azerbaijan to defend its own lands. Armenia should be told to stop. Turkey is doing its part, is doing in accordance with international rules. When you look at this support in terms of international law, we see it as the defense of Azerbaijan's own rights and laws.[61]

Syria

Kılıçdaroğlu has criticized the Turkish government's intervention in Syria's internal affairs.[62] He also has explicitly supported the deportation of Syrian refugees from Turkey, citing economic strain on citizens and the alleged desire of humans to live in their region of birth.[63][64]

Greece

Kılıçdaroğlu has referred to Erdoğan and Mitsotakis as "populists who play [the] war card as their votes are declining" amid the recent increasing tension between two countries over the Aegean Islands. Although he declared his aim to improve relations with Greece, Kılıçdaroğlu strongly opposed the militarization of Greek Islands.[65]

Russia and Ukraine

Kılıçdaroğlu has approved of Erdoğan's "balanced" handling of the Russia-Ukraine War, and the Black Sea Grain Initiative. He promised to continue construction of the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant, which is being built by Russian contractors.[66]

Personal life

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu and his wife, Selvi Gündüz, have a son, Kerem, two daughters, Aslı and Zeynep, and a granddaughter from Aslı's marriage.[67]

In 1950s, his father changed their surname from Karabulut to Kılıçdaroğlu, since all the other people in their village had the same surname.[68] Kılıçdaroğlu's family is also locally known as the Cebeligiller and belongs to the Kureyşan tribe,[69] which is one of the most prominent Zaza tribes.[70] Kılıçdaroğlu married a former journalist, who is also his relative, Selvi Gündüz, in 1974.[71][72]

Kılıçdaroğlu has an intermediate grasp of French[73] and is a passive speaker of Zazaki, being more accustomed to the dialect of the Bingöl region.[74] When the then AK Party deputy chairman Hüseyin Çelik questioned his origins, Kılıçdaroğlu claimed descent from Turkmens from Khorasan who first settled in Akşehir and arrived in Dersim after the Battle of Chaldiran. He also noted himself as a descendant of the Sufi mystic Seydi Mahmut Hayrani, whose tomb is located in Akşehir.[75] While some journalists have denoted his Alevi identity,[76][72] Kılıçdaroğlu refrained from making statements about his religious beliefs for a long time, and in July 2011, he reaffirmed his Alevi identity but refused to delve into ethnic and religious politics.[77]

Works

Kılıçdaroğlu has four published books and many articles:[78]

- İşsizlik Sigortası Kanunu-Yorum ve Açıklamalar, (1993) (Unemployment Insurance Law-Interpretations and Explanations)

- 1948 Türkiye İktisat Kongresi, (1997) (1948 Economics Congress of Turkey)

- Kayıtdışı Ekonomi ve Bürokraside Yeniden Yapılanma Gereği, (1997) (Underground Economy and the Requirement of Reorganisation in the Bureaucracy)

- Özgür ve Adil Bir Türkiye İçin Yürüyüş, (2020) (March for a Free and Just Turkey)

Electoral history

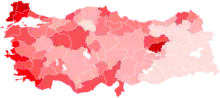

Presidential

| Election date | Votes | Percentage of votes | Map | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

25,504,552 (2nd round) |

47.82% |

|

2nd |

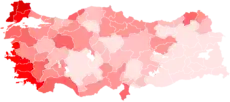

Parliamentary

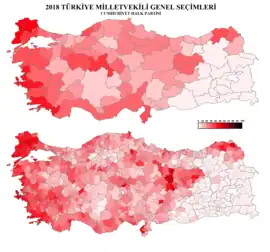

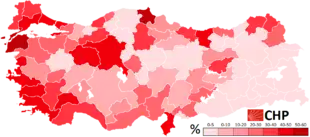

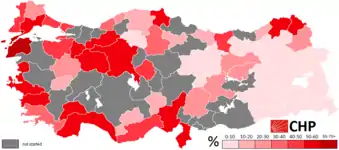

| Election date | Votes | Percentage of votes | +/– | Political party | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 11,155,972 | 25.98% | New | Republican People's Party |  |

| 2015 June | 11,518,139 | 24.95% |  | ||

| 2015 November | 12,111,812 | 25.32% | .png.webp) | ||

| 2018 | 11,354,190 | 22.65% |  | ||

| 2023 | 13,791,299 | 25.33% |

Local

| Election date | Votes | Percentage of votes | +/– | Political party | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 10,938,262 | 26.34% | New | Republican People's Party |  |

| 2019 | 12,625,346 | 29.81% |  |

Istanbul

| Election date | Votes | Percentage of votes | +/– | Political party | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2,568,710 | 36.98% | New | Republican People's Party |  |

References

- Bildirici, Faruk (27 June 2010). "Kılıçdaroğlu Kemal Bey'i anlatıyor". Hürriyet. Archived from the original on 29 June 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- "İşte Kılıçdaroğlu'nun doğduğu ev" Archived 27 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine. CNN Türk. Retrieved 17-11-2022.

- "DSP'nin yıldızları". Sabah (in Turkish). 9 January 1999. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- "68 kuşağının kökten solcu sakin gücü!, siyasilerin bilinmeyenleri" Archived 2 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Habertürk. Retrieved 2-12-2022.

- "Exclusive: The Man Who Could Beat Erdoğan". Time. 27 April 2023.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu 'Bozkurt Kemal' sloganlarıyla karşılandı" (in Turkish). 12 September 2022.

- "Gençlerin demokrat amcası Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, Gençlik Kolları İl Başkanları Toplantımıza katıldı" (in Turkish). 13 August 2022.

- "Kime oy vereceksiniz sorusuna bu yanıtı verdi: Piro - Leblebi Gaffa" (in Turkish). 3 April 2023.

- Murat Yekin (25 July 2022). "Embracing Mr Kemal: Opposition's groundswell".

His second message was to CHP leader Kılıçdaroğlu whom he calls "Mr Kemal" in an effort to undermine his position in conservative voters' eyes. He challenged him to "face him" in the election as the opposition's presidential candidate. Kılıçdaroğlu's biggest surprise in his rally on July 24 was an additional single line on his Twitter bio. CHP leader included "Mr Kemal (Bay Kemal)" in his Twitter biography, embracing the nickname that the president has been using to villainize him.

- Bildirici, Faruk (27 June 2010). "Kılıçdaroğlu Kemal Bey'i anlatıyor". Hürriyet. Archived from the original on 29 June 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- Yalçın, Soner (23 May 2010). "Kılıçdaroğlu hakkında bilinmeyen tek gerçek". Hürriyet (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- "Nazımiyeli ailenin okuyan tek çocuğu". Radikal (in Turkish). 23 May 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "The Turkish opposition: Gandhi's rise". The Economist. 28 April 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Party Leader Biography Archived 4 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine, chp.org.tr, Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- Party Leader Biography Archived 4 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine, chp.org.tr Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- "Devlet boşaldı". Hürriyet. 3 December 2022. Archived from the original on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- "CHP'nin İstanbul adayı Kılıçdaroğlu". CNN Turk (in Turkish). 23 January 2009. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu announcement splits Turkish opposition party". Hürriyet Daily News. 17 May 2010. Archived from the original on 19 May 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu receives broad support from party base". Hürriyet Daily News. 18 May 2010. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Habib Güler (21 May 2010). "Baykal announces he will not run as debate heats up over new CHP". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- "CHP delegates convene to elect new leader". Today's Zaman. 22 May 2010. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- "CHP'de tarihi kurultay". Habertürk (in Turkish). 22 May 2010. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- İzgi Güngör (22 May 2010). "Kılıçdaroğlu wins CHP leadership, challenges Turkish PM 'Mr. Recep'". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- "Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu new leader of opposition Party CHP". National Turk. 22 May 2010. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Delphine Strauss (21 May 2011). "Turkey's Gandhi chosen to lead opposition". The Financial Times. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Head, Jonathan (11 September 2010). "Why Turkey's Constitutional Referendum Matters". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- "CHP most assertive in search for candidates ahead of June elections". Sunday's Zaman. 25 January 2011. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- "Main Turkish opposition receives more than 3,000 candidate applications". Hürriyet Daily News. 22 March 2011. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- "Haberal becomes member of CHP for candidacy in polls". Today's Zaman. 12 March 2011. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- Villelabeitia, Ibon (12 April 2011). "Trailing in polls, Turkey's opposition seeks new face". Reuters. Ankara. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- Villelabeitia, Ibon (12 April 2011). "Trailing in polls, Turkey's opposition seeks new face". Reuters. Ankara. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu'ndan seçim sonuçlarına ilk yorum". CNN Türk. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- Toksabay, Ece (25 August 2016). "Turkish opposition leader targeted by Kurdish militants - minister". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- "PKK: Artvin saldırısını üstleniyoruz; hedef Kılıçdaroğlu değildi" [PKK: We claim responsibility for the Artvin attack, Kılıçdaroğlu wasn't the target]. BBC News Türkçe (in Turkish). Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- "Turkish gov"t calls time on referendum result debate, as opposition vows further objections - POLITICS". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Turkish opposition appeals referendum on Erdoğan powers". Reuters. 21 April 2017. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Leader of the Republican People's Party, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu..." Getty Images. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- Okuyan, Kemal (14 April 2017). "Opinions on the next day of Turkey's referendum". Sol International. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- SigmaLive. "Yildirim makes 'Grey wolves' symbol in Turkish parliament | News". www.sigmalive.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- "Exclusive: The Man Who Could Beat Erdoğan". Time. 27 April 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- "Helalleşme Yolculuğu Başlıyor". Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (in Turkish) Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- "Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu'nun 'adaylığa hazırım' sözlerine 6'lı masadan yanıt geldi". Cumhuriyet (in Turkish). Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu’nun 'Adaylığa hazırım' mesajı, 6’lı masada nasıl yorumlandı?". BBC News Türkçe (in Turkish). Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- "İBB Başkanı İmamoğlu: Her CHP'linin adayı Kılıçdaroğlu'dur". NTV. Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- "Mansur Yavaş'tan Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu'na adaylık desteği". NTV. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- "Son Dakika: Millet İttifakı'nın Cumhurbaşkanı adayı Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu". www.cumhuriyet.com.tr (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- "PES stands firmly behind opposition candidate Kılıçdaroğlu in the Turkish presidential election". The Party of European Socialists. 7 March 2023. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- "Avrupa Sosyalistler Partisi'nden Kılıçdaroğlu'na adaylık desteği". Haber7 (in Turkish). 8 March 2023. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- Sezer, Can; Kucukgocmen, Ali; Hayatsever, Huseyin (28 May 2023). "Turkey's Erdogan prevails in election test of his 20-year rule". Reuters. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- Fraser, Suzan. "Challenger in Turkey presidential race offers sharp contrast". Associated Press. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- "Erdoğan sues Turkey's main opposition leader over dictator remark". Reuters. 18 January 2016. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2017. An Ankara protester also opened an investigation into whether Kılıçdaroğlu's were "openly insulting" to the President.

- "Turkish opposition leader Kılıçdaroğlu is re-elected despite recent poll defeat". The Japan Times Online. 17 January 2016. ISSN 0447-5763. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Main opposition CHP leader slams Euro court for rejecting post-coup appeals - POLITICS". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu meets with HDP co-chairs, says parliament is the address of Kurdish issue". Gazete Duvar. 20 March 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- Soylu, Ragip (25 April 2023). "Turkey elections: Kilicdaroglu says he will back Bayraktar TB2 maker". Middle East Eye. Ankara.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu: Ben Bahçeli gibi değilim, gerçek milliyetçiyim, gerçek ülkücüyüm". 31 May 2022.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu: Bizim milliyetçilik anlayışımız vatanseverliktir" (in Turkish). TRT. 6 May 2023.

- Malsin, Jared; Kivilcim, Elvan. "WSJ News Exclusive | Turkey's Top Election Challenger Pledges Closer Ties to NATO and EU". The Wall Street Journal. Photographs by Furkan Temir for The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- Canikligil, Razi. "Opposition leader vows to stand with West if elected". Hurriyet Daily News. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- "CHP leader vows to 'establish peace' in Mid East if elected". 11 April 2023. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- "We stand by Azerbaijan under all circumstances, says CHP leader". 30 September 2020. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu'ndan Erdoğan'a: "Taşeron olma"". CNN Türk. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- "Main opposition CHP Chairman Kılıçdaroğlu promised to send nearly 2 million Syrian refugees back to their hometowns if CHP wins elections - Mosaic Initiative". Mosaic Initiative. 24 April 2015. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- "If one person makes mistake, the whole country will have to pay for it: CHP leader - POLITICS". Hürriyet Daily News | LEADING NEWS SOURCE FOR TURKEY AND THE REGION. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- "Main opposition CHP chair on Erdoğan and Mitsotakis: 'Two populists playing war card'". Duvar English (in Turkish). 9 December 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- Soylu, Ragip (24 April 2023). "Turkey elections: What is the opposition's Russia policy?". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- "Nazımiyeli ailenin okuyan tek çocuğu". Radikal (in Turkish). 23 May 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Nazımiyeli ailenin okuyan tek çocuğu". Radikal (in Turkish). 23 May 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu'nun serüveni". NTV. (in Turkish). 21 May 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- Asatrian 1995, p. 405–411.

- "İşte 'Gandi Kemal'in yaşam hikayesi". Hürriyet (in Turkish). 24 May 2010. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Zaman, Amberin (23 May 2022). "Will Turkish opposition leader's Alevi faith be hindrance at polls? - Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- "TÜRKİYE BÜYÜK MİLLET MECLİSİ". 4 March 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu: Kurultayda 'Dersimli Kemal'im dedim". Artıgerçek (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

Kılıçdaroğlu'na anadil ile ilgili soru da yöneltildi. Kürt Dil Platformu Sözcüsü Şerefxan Ciziri, "Kaç gündür Diyarbakır'dasınız. Dersimlisiniz, anadiliniz Zazakî. Ama anadilinizde tek kelime duymadık sizden" diye sordu. "Hiç Zazaca konuştunuz mu" sorusuna Kılıçdaroğlu, "Hayır konuşmadım, çünkü bilmiyorum. Ama annem ve babam biliyorlardı. Ama anlıyorum. Bingöl'ün Genç ilçesinde kaldım. Tunceli'de konuşulan dil ile, Palu Genç bölgesinde konuşulanla arasında fark var. Dolayısıyla Bingöl'deki Zazacayı daha iyi anlıyorum. İlkokulu, ortaokulu orada okudum" cevabını verdi.

- "Kılıçdaroğlu'nun kökleri Kirmanşah'a mı dayanıyor?" (in Turkish). Independent Türkçe. 24 October 2021. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

Sayın Çelik'e önerim şu, gitsin Akşehirlileri sorsun. Benim dedemin türbesi Akşehir'de, şimdi ben bunu yok mu sayayım? Gitsin araştırsın. Dedem Seyit Mahmud Hayranî'dir. Biz Horasan'dan gelmiş bir Türkmen boyuna mensubuz. Horasan'dan gelip Konya'nın Akşehir'ine yerleşmişler. Sonra Yavuz Sultan Selim-Şah İsmail savaşı olunca da Dersim'e göç etmişler. Türkmen boyundan geliyorlar. Kürt değiller. Ama ben etnik kökenle ilgili biri değilim.

- Turkey’s opposition: A new Kemal: Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu gives new hope to the Turkish opposition Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Economist, 27 May 2010, Ankara.

- "Alevi'yim ne var bunda". CNNTurk (in Turkish). 17 June 2011. Archived from the original on 19 September 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- "TÜRKİYE BÜYÜK MİLLET MECLİSİ". 4 March 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

Sources

- Asatrian, Garnik (1995). "DIMLĪ". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. VI. Fasc. 4. pp. 405–411. ISBN 978-0933273634.

Dimlī society is tribal, a sociopolitical, territorial, and economic unit organized according to genuine or putative patrilineage and kinship, with a characteristic internal structure. It encompasses forty-five subtribes, each divided into smaller units. The most prominent are Ābāsān, Āḡāǰān, Ālān, Bāmāsūr(ān), Baḵtīār(lī), Dǖīk, Davrēš-Gulābān, Davrēš-Jamālān, Hay-darān(lī), Hasanān(lī), Korēšān, Mamikī, and Yūsufān.

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

(in Turkish)

(in Turkish) - Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu's biography at TBMM's website (in Turkish)

- A Long March for Justice in Turkey (Gastbeitrag, www.nytimes.com 7 July 2017)