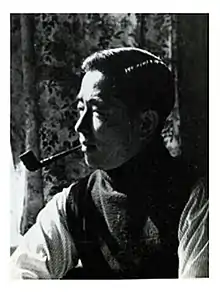

Kenichiro Matsuoka

Kenichiro Matsuoka (松岡 謙一郎, Matsuoka Kenichiro, June 13, 1914 – December 23, 1994) was a Japanese media executive. He founded and served as the first President of Japan Cable Television, and as a Vice President of Asahi Broadcasting Company (now TV Asahi).[1]

Kenichiro Matsuoka 松岡 謙一郎 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 13, 1914 Washington, D.C., United States |

| Died | December 23, 1994 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Occupation | Media Executive |

| Parent(s) | Yōsuke Matsuoka Ryuko Matsuoka (Shin) |

| Relatives | Kaneko (sister) Yoji (brother) Hiroko Satō (cousin) |

Biography

The eldest son of Japanese foreign minister Yōsuke Matsuoka, Kenichiro was born in the United States while his father was First Secretary of the Embassy of Japan, Washington, D.C., attended Gyōsei High School and Tokyo Imperial University, majoring in Political Science and Law.[2][3]

When his father took over leadership of the South Manchuria Railway (Mantetsu), Kenichiro became involved with the Manchukuo Film Association (Man'ei), formed in partnership with Mantetsu. Through Man'ei, Kenichiro would meet Negishi Kanichi and Masahiko Amakasu, who gave him experience in building a film studio from the ground up. Kenichiro would also meet the popular pre-war Japanese actress Yoshiko Yamaguchi, whom Yamaguchi would write in her biography "Ri Kōran: My Half Life", to be her first love. They would meet again after the war, at which time Kenichiro attempted to rekindle the relationship, but by then, Yamaguchi was already involved with the noted designer Isamu Noguchi.[4]

Graduating Tokyo Imperial University in 1941, there was talk of Kenichiro attending school in America to defuse any suspicion of Japan's war ambitions, and he would join the state run news agency Dōmei Tsushin that would be broken up by Allied forces during the Occupation of Japan. During the war, he would also serve as an accounting officer for the Imperial Navy, and followed Yōnosuke Natori to the Sun News Photo agency following Dōmei's breakup.

In 1957, Matsuoka joined the fledgling Nippon Educational Television Board (NET) television network.[5][6][7][8] [9] NET courted Matsuoka for his knowledge of foreign culture and fluency in English and French, having been born in the United States, studied in Paris, and experienced with Mantetsu. He was able to watch foreign programming in its original format and was responsible for licensing Rawhide and Laramie, gaining high ratings for the new network, and giving them an advantage over rivals NHK and Fuji TV.[10][11]

By the time NET parent company Asahi Shimbun would rebrand the network as Asahi Broadcasting Corporation in 1977, Matsuoka would be promoted to Executive Vice President (Fuku-shacho) at Asahi Broadcasting Co, serve as a founder of Japan Cable Television, and act as its first president, a position he held until his retirement in 1986.[12][13][14]

Legacy

Kenichiro was portrayed in the film Ri Kōran by Fukami Motoki.[15]

Family

Kenichiro's father Yōsuke, was a prominent diplomat in pre-war Japan.[16] Kenichiro's mother Ryuko, was the daughter of an influential kuge judge Shin Soroku, a former retainer of the Chōshū clan, and a beneficiary of their outsized influence in the Meiji Restoration that helped shaped the modern Japanese Government. Yōsuke's sister Fujie was widowed in 1911 with two young girls, whom Yosuke supported as if his own.[17] One of those nieces, Hiroko, married future Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Satō, and ties Kenichiro to the Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the Abe political dynasty through Abe's maternal grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, Eisaku's older brother.[18]

References

Wikipedia Japan article on Kenichiro Matsuoka - (jp:松岡謙一郎)

- Business Japan. 北泉社. 1987. ISBN 9784938424107.

- Yamaguchi, Yoshiko (2015). Fragrant Orchid: The Story of My Early Life. University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 135–141. ISBN 9780824854041.

- "Matsuoka Yosuke". kotobank.jp. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- Yamaguchi, Yoshiko (1987). Ri Kōran: My Half-Life. Shinchosha. ISBN 9784103667018.

- "Son of Matsuoka, Minister of Foreign Affairs, to study abroad". The Hawaii Times. 7 March 1941. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- Huffman, James (2006). Modern Japan, An Encyclopedia of History, Culture and Nationalism. Garland. ISBN 0-8153-2525-8.

- Political Handbook of Japan. Tokyo News Service. 1949.

- "戦後グラフ雑誌と…". 週刊サンニュース. 5 February 1949. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- Kambayashi, Yutaka (2006). Setting Sun. Aperture. ISBN 9781931788830.

- KINOSHITA, Koichi (2019). Translation Norms in Early Television Broadcasting in Japan. Japanese Journal of Communication Studies.

- Hasegawa, Soichi (2008). Memories of the early days of Saturday Western Theater. TV Asahi. pp. 78–85.

- "NET TV Shareholders Meeting". Shibuzawa Company History Database. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- "Japan Cable Television (JCTV) Company Overview" (PDF). Japan Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. 2013-01-23.

- Monthly Broadcast Journal vol 11. Broadcast Journal. 1981.

- "李香蘭". tv-tokyo.co.jp. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- Matsuoka, Kenichiro (23 August 1964). "Oyajoyaji: Matsuoka Yosuke". Shūkan Asahi.

- David Jon Lu, Agony of Choice: Matsuoka Yosuke and the Rise and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1880-1946 (Lexington Books, 2002)

- Krebs, Albin (3 June 1975). "Eisaku Sato Ex‐Premier of Japan, Dies at 74". New York Times.