Kenora Thistles

The Kenora Thistles, officially the Thistles Hockey Club, were a Canadian ice hockey team based in Kenora, Ontario. Founded in 1894, they were originally known as the Rat Portage Thistles. The team competed for the Stanley Cup, the ice hockey championship of Canada, five times between 1903 and 1907. The Thistles won the Cup in January 1907 and defended it once before losing it that March in a challenge series. Composed almost entirely of local players, the team comes from the least populated city to have won the Stanley Cup. Nine players—four of them homegrown—have been inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame, and the Stanley Cup champion team was inducted into the Northwestern Ontario Sports Hall of Fame.

| Kenora Thistles | |

|---|---|

| |

| City | Kenora, Ontario, Canada |

| League | MNWHA, MHA |

| Founded | 1894 |

| Home arena | Princess Rink (1894–1897) Victoria Rink (1897–1907) |

| Franchise history | |

| 1894–1905 | Rat Portage Thistles |

| 1905–1908 | Kenora Thistles |

| Championships | |

| Regular season titles | 1902, 1904, 1906, 1907 |

| Stanley Cups | January 1907 |

Though Kenora is in Ontario, the Thistles competed in Manitoba-based leagues throughout their existence, owing to the city's proximity to that province. The team joined the Manitoba Hockey Association (MHA) in 1902, winning the league championship in three of their six seasons. They were idealized "as a team of hometown boys who used to play shinny together on the streets of Rat Portage". The Thistles were unable to cope with the advent of professionalism in ice hockey during the early 1900s. This combined with an economic downturn in 1907, and being unable to sustain their success, the team disbanded in 1908. The name "Thistles" has been used since for several senior, minor, and junior Kenora teams.

Early years (1894–1902)

Town development

In 1836 the Hudson's Bay Company established a factory (trading post) north of the current city of Kenora.[1] They named it Rat Portage, a translation of the Ojibwe-language name for the region: Waszush Onigum, which literally means "the road to the country of the muskrat".[2] Around 1850 gold was discovered in the region, and the Canadian Pacific Railway reached it in 1877. A sawmill was established in 1880. The town was incorporated in 1882, originally within the province of Manitoba.[1] Located near the Manitoba–Ontario provincial border, the region was contested by both provinces until the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council ruled in favour of Ontario in 1884.[3] Its closer proximity to Winnipeg, 210 kilometres (130 mi) away, and the rest of Manitoba, meant Rat Portage had closer ties with the west than with the rest of Ontario, where the closest city was Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay), 500 kilometres (310 mi) away.[1]

With the railroad connecting Rat Portage to Central and Eastern Canada, the town grew quickly, going from only a few people before the railway link, to 5,202 in 1901 and 6,257 by 1908. The town grew to support several industries, mainly lumber, mining, and fishing but also milling, power development and tourism.[4] An ice rink called the Princess Rink was built in 1886. It was replaced in 1897 by the Victoria Rink which had more seats (1,000) and a larger ice surface.[5] The town's name was changed on May 11, 1905, to Kenora, which was derived from the first letters of the three neighbouring municipalities: Keewatin, Norman, and Rat Portage.[4][6] The change occurred due to the establishment of a new flour mill in town; sports historian John Wong has suggested that local businessmen felt the name Rat Portage would not encourage sales of flour.[7]

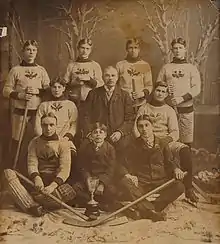

Formation of the Thistles

The first recorded ice hockey game played in Rat Portage was on February 17, 1893,[lower-alpha 1] organized by the Hardisty brothers, who had recently moved from Winnipeg to take part in a minor gold rush in the region.[4][5] A club was formed in 1894, with a contest held to name it; the winning entry, "Thistles", was chosen by Bill Dunsmore, a carpenter with Scottish heritage.[8] George Dewey, one of the wealthiest people in the town, donated the initial funds for the team. In recognition he was named the club's honorary president. Most of the players were from wealthy families or independently wealthy. They had the means both to take time off work and to cover the considerable expenses associated with ice hockey.[9]

The club had no owner or financial backer and, apart from Dewey's initial donation, local businesses never supported it financially. It was a community effort, with officers elected to make decisions for the club.[10] As a result, the club was strained financially and would be throughout their existence. In March 1894 they successfully hosted a benefit concert to raise funds. Though a similar attempt the following year did not bring in as much money, concerts were held yearly until 1903.[9]

Initially, the games were played within the club, but the players quickly grew tired of this. In 1894 the team was admitted to the Manitoba and Northwest Hockey Association, and entered the second-tier intermediate level.[11] Though based in Ontario, the Thistles joined the Manitoba league because they were geographically closer to its teams.[1] In their first season they won twelve games, showing they could easily compete at that level.[lower-alpha 2]

In January 1896 a game was held in Kenora between the senior team and a junior-aged team, with players aged 12–16.[12] The junior players, many of whom were related to players on the senior team, felt they could compete with the older team, and subsequently won, easily defeating their opponents.[13] In a 1953 newspaper article on the match Lowry Johnston, who was on the senior team, explained, "They were just too fast for us."[14] A legend developed that the senior team quit hockey after that match, letting the junior players take their place in the Manitoba league.[15] While this may not have happened as quickly as suggested, many of the players from the junior team soon joined the senior team and would hold major roles on the Thistles.[14]

Bolstered by the younger players, the Thistles finished second in the Manitoba intermediate league in 1899–1900 with a record of four wins and four losses.[16] They finished tied for first in the league in 1900–01; after winning a one-game tiebreaker they were declared champions, finishing with a record of nine wins and two losses. During the season they outscored their opponents 67 to 32, and their two losses had been by one goal each.[17] When the team started the 1901–02 season with a lopsided 12–0 victory, the club's executives became concerned. They felt if the games were not competitive people would not come to watch them, resulting in less revenue.[14] Believing the team was strong enough to move up, they applied to join the senior Manitoba Hockey Association, which had two teams that season, both in Winnipeg: the Victorias and the Winnipeg Rowing Club.[18] To prove they could compete, the Thistles played an exhibition match against the Victorias, one of the best teams in Canada, and a previous winner of the Stanley Cup, the championship trophy of ice hockey in Canada. The Thistles fared well in the match, but the two Winnipeg teams decided against allowing them to join the league, arguing the Thistles applied too late in the season.[19] Returning to the intermediate league, the Thistles, weakened by injuries to several players, finished in a tie for second overall.[19] After the season ended Tommy Phillips, one of the best players on the Thistles, moved to Montreal to attend McGill University.[20]

Admission to the Manitoba Hockey Association

League play, 1902–1905

Before the 1902–03 season the Thistles were admitted to the senior league, along with Brandon Wheat City and the Portage la Prairie Plains.[11] The two Winnipeg teams, still concerned about the distance to Rat Portage, opposed their inclusion (and that of Portage la Prairie), stating they would play only against Brandon, the winner of the intermediate championship in 1902. Thus, the two Winnipeg clubs left the league before the start of the season and formed their own two-team league, the Western Canada Hockey League.[19] Playing in the new three-team senior league, the Thistles won the championship and were allowed to issue a challenge for the Stanley Cup, held at the time by the Ottawa Hockey Club (also known as the Senators).[11]

For the 1903–04 season the Thistles competed again in the three-team Manitoba league. Prior to the season, the team was invited to join the Western Canada Hockey League, which still had only the two Winnipeg clubs. While they had downplayed the Thistles' importance before, the Winnipeg clubs were impressed by their play during the Stanley Cup challenge and considered it financially viable to add the team. The Thistles declined the offer and remained in the Manitoba league.[21] Kenora finished second in the league with eight wins and four losses.[22] Brandon won the league championship, and earned the chance to compete for the Cup against Ottawa, who won the series and retained it.[23]

Before the 1904–05 season the two Manitoba leagues merged to become the Manitoba Hockey Association.[24] The Thistles were bolstered by the presence of Tommy Phillips (who had returned to visit his dying father) and goaltender Eddie Giroux, the only player not from Rat Portage. Giroux moved from Toronto with the promise of a job in the lumber industry and for a chance to play ice hockey.[25][lower-alpha 3] The Thistles easily won the league championship, finishing with a record of seven wins and one loss, and again challenged Ottawa for the Stanley Cup.[27][28]

1903 Stanley Cup challenge

Donated in 1892 by Lord Stanley of Preston, the Governor General of Canada, the Stanley Cup was originally awarded to the top amateur team in Canada, who would then accept challenges from the winners of other leagues.[29] From its inception until 1912, the Cup was nearly always won by teams from Montreal, Winnipeg, and Ottawa.[30] In 1903 Ottawa won the Cup, after finishing the season tied for first in the Canadian Amateur Hockey League with the Montreal Victorias. They played a two-game, total-goal series for the league championship. The Montreal Hockey Club, who had held the Cup, finished third in the league and therefore lost the right to keep it.[23]

The Thistles travelled to Ottawa for a two-game series to be decided on total goals scored. Relatively unknown outside Manitoba and Western Ontario, there was little press coverage of the team before the start of the series.[31] Attendance at the games was rather low as the series coincided with an opening session of the Canadian Parliament, which was a social affair at the time. While the matches between Ottawa and Montreal, held just days earlier, attracted around 3,000 spectators, the Thistles' games saw 1,500 and then 1,000 viewers.[19][32] Ottawa won the first game 6–2, media summaries suggesting the Thistles were nervous and unprepared for Ottawa's skilled play.[33] Ottawa won the second match 4–2 and retained the Cup. Though the press credited the Thistles for being vastly improved, they felt that overall the team lacked "the finer points of the game".[32][33]

The Thistles had a mixed reaction to their first Stanley Cup challenge. Small crowds made it a financial failure; the team lost about C$800, a considerable sum at the time.[32] It was still seen as an important step for the team, as it showed they could compete with the best teams in Canada.[34] Team captain Tom Hooper said that while they "were comparatively inexperienced, and ... consequently a little nervous", they were "not in the least discouraged" and planned to "be better qualified to play them when [they] come after the puck next year".[32]

1905 Stanley Cup challenge

The Cup challenge was again played in Ottawa, this time in a best-of-three series. Media reports about the Thistles were more positive than those of 1903, the team being regarded as a strong chance for the Cup.[35] Attendance for the series was considerable; the games attracted between 3,500 and 4,000 spectators, and hundreds more waiting outside for entry. There were also thousands across Canada who eagerly waited in newspaper offices and other venues for live telegraph reports on the games.[36] Newspaper reports made a point of mentioning the home-grown nature of the team as some of them had begun to use professionals.[37][38]

The Thistles won the first match 9–3, using a new style of play. With forward passing forbidden in ice hockey, conventional strategy was for teams to shoot the puck into the opposing end and skate after it (thereby losing possession of the puck). Instead, as they moved forward, the Thistles emphasised skating and passing the puck back and forth keeping control of it.[25] This strategy was aided by their point and cover-point men (early names for defencemen) who lined up on the ice side-by-side rather than one in front of the other as was common.[28] Ottawa's star Frank McGee had missed the first game. He returned for the succeeding games, helping Ottawa to win the remaining games, 4–2 and 5–4, and retain the Cup.[39] Though the Thistles lost the challenge, they were praised, newspapers noting the players' speed in particular. The Montreal Star claimed the Thistles were not only the fastest team from the west to challenge for the Cup, but the fastest "ever ... seen anywhere on ice".[36] Before heading home after the series, the team played exhibition matches in Montreal and Toronto attracting thousands of spectators.[36]

Stanley Cup champions

League play, 1905–1907

The 1905–06 season saw Kenora (as the town had been renamed) finished tied for first the Winnipeg Hockey Club with a record of seven wins and one loss, and winning the league championship after a one-game tie-breaker.[40] This allowed Kenora to issue another challenge for the Cup, scheduled for January 1907.[41][42] Due to fears that teams were covertly paying their players, the Winnipeg Rowing Club, which had been expected to play in the MHA, withdrew. As ardent followers of amateurism (Canadian sporting rules made anyone who played against a professional a professional as well) the club could not take part and had been replaced by the Winnipeg Hockey Club. The other league teams denied paying players, the Thistles calling the accusations "ridiculous".[43] Despite these denials, it is quite likely there were paid players in the league. Sports historian R.S. Lappage has noted that by this point "it was generally recognized that most eastern teams were paying their players, and it would be reasonable to expect that teams of the M.H.L. ... had to pay their star players to retain their services".[43] As early as 1903 financial offers had been made to players from the International Hockey League based in Michigan—the first openly professional ice hockey league in the world.[38]

Before the start of the 1906–07 season the issue of professionalism came up again for the Manitoba league. While most of the league's teams felt it should turn professional, the two Winnipeg teams (the Victorias and Winnipeg Hockey Club) were against this move and left the league.[44] Though the league was now openly professional, the Thistles continued to remain a homegrown team, despite rumours before the season there would be a major overhaul of the roster.[45]

To accommodate the Thistles' challenge against the Wanderers in January, which saw the team gone for nearly a month, modifications to the regular season schedule had to be made. As the Thistles were a popular team and likely to draw large crowds, the other teams wanted a double round-robin format—two home games, two away games against each team. The Thistles were against this, and wanted to play only one home and one away game against the others, as they would be gone for nearly a month for their Cup challenge. Ultimately a compromise was reached. The Thistles would play one home and away game, while the other three teams would play two home and two away. Since this would lead to an unbalanced schedule (the Thistles would have played six games while the other teams had played ten), scores in the games not including the Thistles would be combined for the purposes of the league standings, so all teams would be credited with six games played.[46]

January 1907 Stanley Cup challenge

As the 1906 champions of the Manitoba league, Kenora earned the right to challenge for the Stanley Cup, which was held by the Montreal Wanderers, but the season ended too late for the series to be held that year. It was postponed until January 1907, during the league's regular season play.[42]

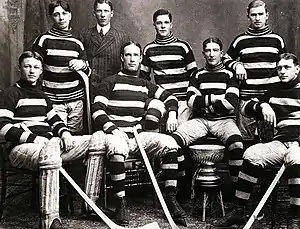

The Thistles left for Montreal and the Cup challenge on January 12, 1907. Taking advantage of the new professionalism of their league, the club hired Art Ross, and Joe Hall from Brandon, considered two of the best players in the Manitoba league. It is unclear how much they were paid for the series, but ice hockey historian Eric Zweig has speculated the amount was substantial (though Hall did not play any games for the Thistles).[47] This marked the first time the Thistles had paid players on the team and confirmed their status as a professional club.[34] The Wanderers, by contrast, had five professional players and four amateurs on their roster. The Eastern Canada Amateur Hockey Association (ECAHA), the Wanderers' league, allowed professionals beginning in the 1906–07 season as long as each players' status was defined by the team.[47]

Though the Thistles hired two professional players, the media again emphasized the team consisted mainly of local amateurs, and noted the Wanderers had hired multiple professional players, most notably Hod Stuart, who had played previously for the Pittsburgh Professionals.[48][49] Even so, the consensus was that the Thistles were the favourites to win the Cup.[50] The first game of the two-game, total-goal series was held on January 17 in Montreal. Tommy Phillips scored all four Kenora goals in a 4–2 victory.[25] The second game, on January 21, saw him record a further three goals, as Kenora won 8–6, giving them a 12–8 series win and the Stanley Cup.[51] Following tradition, the Thistles had their name engraved on the Cup. Unlike previous winners who wrote on the side of the bowl, the Thistles had "Thistles of Kenora 12 Wanderers 8 / Montreal Jan 17th & 21st 1907" engraved inside it.[52]

On their return to Kenora later in January, the Thistles were warmly received; a reception at the Opera House saw each player given a commemorative cup by the city, among other gifts.[49] The team's dire financial situation meant that an admission was charged for the celebratory banquet, unusual for similar events at the time.[34] There were signs of improved finances, though. The owners of the Victoria Rink where the team played, stated their intention to build a 4,000 to 5,000-seat replacement rink. This would have made it the largest rink west of Ontario and dwarf the 1,000-seat Victoria Rink. This was suggested as a solution to the team's financial issues since they would earn a portion of each ticket sold.[49][34]

March 1907 Stanley Cup challenge

Almost immediately after the Thistles won the Stanley Cup the Wanderers, who had won the ECAHA championship, issued a challenge for a re-match; William Foran, one of the Cup's trustees, told the Thistles they first had to win the Manitoba league title.[53] Brandon and the Thistles finished in a tie for first, so a two-game total-goal series was played to decide the league championship; Kenora won both games, 8–6 and 4–1. Though this series determined who would play the Wanderers for the Cup, it was not initially regarded as a challenge series and only later confirmed as such by Cup trustees.[54]

The Thistles signed three new players, as the league season and Cup challenge had seen regular players—Hooper, Billy McGimsie, and Phillips—sidelined by injuries.[55] Fred Whitcroft, who had played in Peterborough, Ontario, was signed for the rest of the season for a reported $700.[56] To further bolster the team for the Cup challenge, the Thistles signed Alf Smith and Harry "Rat" Westwick, both from the Ottawa Hockey Club; each player made their debut in the league's final season game and played in the series against Brandon.[57] Smith and Westwick's signings drew protests from the Wanderers. They argued that since they spent the entire season with Ottawa in the ECAHA they should not be eligible to play for Kenora, as players had to play the full season with their team. The Thistles countered by arguing that the Wanderers brought in Hod Stuart and Riley Hern back in January. Foran defended the choice to allow Stuart, noting there had been no protest in January, and said that since Stuart and Hern spent the season with the Wanderers they were eligible.[58][59]

A further issue arose when Foran told the Thistles that owing to the larger arena in Winnipeg, providing greater revenue from ticket sales, the series would be played in Winnipeg, not Kenora. It would begin the day after the Thistles finished their series with Brandon and would be a best-of three-game series. The Thistles were irate. They wanted to host the series, have a three-day break before it, and play a two-game, total-goal series.[55] They discussed the matter with the Wanderers, and both agreed instead to a two-game series in Winnipeg, and that Kenora could use both Smith and Westwick. Foran consented to this arrangement.[60]

With the details of the series settled, the first game was held on March 23, which the Wanderers won 7–2. The Thistles won the second match, on March 25, 6–5, but lost the series 12–8.[61] Reports on the Thistles in the media noted how reliant the team was on their three imported players and that they could no longer be portrayed as a homegrown team.[62] The Thistles' time as Stanley Cup champions ended after two months.[25]

Demise of the Thistles

After losing the Stanley Cup, there were major changes to the Thistles' composition. Roxy Beaudro, Eddie Geroux, and Billy McGimsie retired before the 1907–08 season, while Tommy Phillips joined the Ottawa Hockey Club after being offered $1,500 for the season.[63][64] The team brought up four junior players, all under twenty years old, and were not expected to be as competitive as earlier versions of the team. This was apparent after the first game of the season, which the Thistles lost 16–1.[62] The club forfeited the next two games before withdrawing from the league completely, arguing they could no longer compete at that level. They attempted to join the New Ontario Hockey League, which had teams in Port Arthur and Fort William, but were refused. Instead, the Thistles played exhibition games for the rest of the season before folding.[65]

The Thistles were unable to compete with the rising professionalism that was developing in ice hockey. Located in a small town, they were unable to build a large enough rink, let alone attract the crowds to fill it and raise revenue. The promise of a larger arena, suggested in the wake of the club's Stanley Cup championship, would have been impossible to realize since it would have required the entire town to attend games to sell it out.[34] Compounding the issue was a major economic downturn in the region starting as early as 1905, mining in particular seeing a major collapse.[34] This coincided with the establishment of professional ice hockey leagues across Canada. Along with the Manitoba league, the ECAHA turned fully professional in 1907. The Ontario Professional Hockey League was established the same year and, in 1911, the Pacific Coast Hockey League began in British Columbia. These developments meant the Thistles had to compete with a multitude of teams for players who were being offered higher salaries.[66] As a result, sports historian John Wong has suggested it was unlikely that the Thistles could compete for top-rated players with clubs in larger cities and remain secure financially.[10]

Legacy

Kenora remains the smallest town to win the Stanley Cup, and a major North American professional championship. The Thistles' 65 days as Stanley Cup champions is also the shortest length of time a team has possessed the Cup.[67] Four homegrown Thistles—Si Griffis, Tom Hooper, Billy McGimsie, and Tommy Phillips—were later inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame. The five players signed for their 1907 Cup challenges—Art Ross and Joe Hall from January; Alf Smith, Harry Westwick, and Fred Whitcroft—would also be inducted.[68] The January 1907 Stanley Cup champion team were themselves elected to the Northwestern Ontario Sports Hall of Fame in 1982.[69]

Lappage has noted that during their existence, the Thistles were romanticized in the press "as a team of hometown boys who used to play shinny together on the streets of Rat Portage".[70] That players from the town were responsible for most of the team's success was respected.[4] Further, the players remained active in the community outside hockey. Most took up local jobs, while in the summer several played other sports, particularly rowing—Griffis competed at the 1905 Royal Canadian Henley Regatta—and baseball.[71][39] The team also helped promote Kenora to a wider audience: as a booming town at the turn of the century, town officials were excited by the publicity the Thistles' success brought.[53] Sports historian Stacey L. Lorenz has noted that "Although Kenora's experience of professional hockey was brief, the Thistles' early twentieth-century Stanley Cup challenges [illustrated] some of the key issues surrounding community identity, town promotion, and the amateur-professional controversy in [that] period."[72]

Since the original team's demise in late 1907, the nickname "Thistles" has been used for many ice hockey clubs in Kenora, including the town's amateur, junior, and senior-level men's teams.[73] A plaque was unveiled by the city on August 24, 1960 commemorating the Cup win; two of the three living people from that team (McGimsie and trainer James Link) were in attendance, while Ross was unable to join.[74]

Stanley Cup challenge series results

March 1903 vs Ottawa Hockey Club

| Date | Winning Team | Score | Losing Team | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 12, 1903 | Ottawa HC | 6–2 | Rat Portage Thistles | Dey's Arena |

| March 14, 1903 | Ottawa HC | 4–2 | Rat Portage Thistles | |

| Ottawa won best-of-three series, 2–0[75] | ||||

March 1905 vs Ottawa Hockey Club

| Date | Winning Team | Score | Losing Team | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 7, 1905 | Rat Portage Thistles | 9–3 | Ottawa HC | Dey's Arena |

| March 9, 1905 | Ottawa HC | 4–2 | Rat Portage Thistles | |

| March 11, 1905 | Ottawa HC | 5–4 | Rat Portage Thistles | |

| Ottawa won best-of-three series, 2–1[76] | ||||

January 1907 vs Montreal Wanderers

| Date | Winning Team | Score | Losing Team | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 17, 1907 | Kenora Thistles | 4–2 | Montreal Wanderers | Montreal Arena |

| January 21, 1907 | Kenora Thistles | 8–6 | Montreal Wanderers | |

| Kenora won total-goal series, 12–8[77] | ||||

March 1907 vs Brandon Wheat City

| Date | Winning Team | Score | Losing Team | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 16, 1907 | Kenora Thistles | 8–6 | Brandon Wheat City | Winnipeg Auditorium |

| March 18, 1907 | Kenora Thistles | 4–1 | Brandon Wheat City | |

| Kenora won total-goal series, 12–7[60] | ||||

March 1907 vs Montreal Wanderers

| Date | Winning Team | Score | Losing Team | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 23, 1907 | Montreal Wanderers | 7–2 | Kenora Thistles | Winnipeg Auditorium |

| March 25, 1907 | Kenora Thistles | 6–5 | Montreal Wanderers | |

| Montreal won total-goal series, 12–8[78] | ||||

References

Notes

- There are conflicting dates for the first game: Wong cites a contemporary newspaper report of the game, while Lappage cites a letter published in 1953. See Wong 2006, p. 177 and Lappage 1988, p. 79, and Wong 2006, p. 187 for further details on the discrepancy.

- Historian R.S. Lappage notes they won twelve games, but does not mention how many games were in the season; at the time leagues would play roughly 10–15 games in a season, so the Thistles would have been one of the stronger teams. See Lappage 1988, p. 80.

- Two other players, Matt Brown and Si Griffis, were both born in St. Catharines, Ontario and moved to Rat Portage at a young age.[26]

Citations

- Wong 2006, p. 177

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2079

- Zweig 2022, p. 34

- Lappage 1988, p. 79

- Wong 2006, p. 178

- Danakas & Brignall 2006, p. 64

- Wong 2006, p. 190, note 37

- Lappage 1988, pp. 79–80

- Wong 2006, p. 181

- Wong 2006, p. 185

- Wong 2006, p. 179

- Danakas & Brignall 2006, p. 11

- Danakas & Brignall 2006, pp. 11–16

- Lappage 1988, p. 80

- Danakas & Brignall 2006, pp. 16–17

- Zweig 2022, p. 62

- Zweig 2022, pp. 70–72

- Lappage 1988, pp. 80–81

- Lappage 1988, p. 81

- Zweig 2012–2013a, pp. 9–17

- Wong 2006, p. 180

- Zweig 2022, p. 140

- Diamond 2000, p. 55

- Danakas & Brignall 2006, p. 37

- Zweig 2007

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2082

- Zweig 2022, p. 156

- Lappage 1988, p. 83

- Diamond, Zweig & Duplacey 2003, pp. 15–16

- Diamond, Zweig & Duplacey 2003, pp. 21–23

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2081

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2082

- Danakas & Brignall 2006, p. 35

- Wong 2006, p. 183

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2084

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2085

- Lorenz 2015, pp. 2083–2084

- Wong 2006, p. 182

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2083

- Zweig 2022, pp. 202–203

- Zweig 2012, p. 298

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2086

- Lappage 1988, p. 86

- Zweig 2012, p. 295

- Lappage 1988, p. 87

- Zweig 2006, pp. 7–8

- Zweig 2001, p. 18

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2089

- Lappage 1988, p. 89

- Lorenz 2015, pp. 2087–2088

- Danakas & Brignall 2006, pp. 83–96

- Diamond 2000, p. xii

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2090

- Zweig 2001, pp. 17–20

- Lappage 1988, p. 90

- Lappage 1988, pp. 89–90

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2091

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2092

- Coleman 1964, pp. 145–146

- Zweig 2001, p. 20

- Coleman 1964, p. 137

- Lappage 1988, p. 92

- Danakas & Brignall 2006, p. 108

- Kitchen 2008, p. 159

- Lappage 1988, p. 93

- Wong 2006, pp. 184–185

- Zweig 2022, p. 23

- Zweig 2001, p. 17

- 1907 Kenora Thistles Senior Hockey 2018.

- Lappage 1988, p. 94

- Lappage 1988, p. 82

- Lorenz 2015, p. 2098

- Milton 2014

- Zweig 2022, pp. 24, 30

- Podnieks 2004, p. 33

- Podnieks 2004, p. 35

- Podnieks 2004, p. 38

- Podnieks 2004, p. 39

Sources

- Coleman, Charles L. (1964), The Trail of the Stanley Cup, Volume 1: 1893–1926 inc., Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8403-2941-7

- Danakas, John; Brignall, Richard (2006), Small Town Glory: The Story of the Kenora Thistles' Remarkable Quest for the Stanley Cup, Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, ISBN 978-1-55028-961-9

- Diamond, Dan, ed. (2000), Total Stanley Cup: An Official Publication of the National Hockey League, Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, ISBN 978-1-89212-907-9

- Diamond, Dan; Zweig, Eric; Duplacey, James (2003), The Ultimate Prize: The Stanley Cup, Kansas City, Missouri: Andrews McMeel Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7407-3830-2

- Kitchen, Paul (2008), Win, Tie, or Wrangle: The Inside Story of the Old Ottawa Senators 1883–1935, Manotick, Ontario: Penumbra Press, ISBN 978-1-897323-46-5

- Lappage, R.S. (1988), "The Kenora Thistles' Stanley Cup Trail", Canadian Journal of History of Sport, 19 (2): 79–100, doi:10.1123/cjhs.19.2.79

- Lorenz, Stacy L. (2015), "'The Product of the Town Itself': Community Representation and the Stanley Cup Hockey Challenges of the Kenora Thistles, 1903–1907", The International Journal of the History of Sport, 32 (17): 2078–2106, doi:10.1080/09523367.2016.1149167, S2CID 147202577

- Milton, Steve (April 11, 2014), "Kenora Thistles Have Lots Of History – But Not Much Ice Time", Hamilton Spectator, Hamilton, Ontario, retrieved February 16, 2019

- 1907 Kenora Thistles Senior Hockey, Northwestern Ontario Sports Hall of Fame, 2018, archived from the original on April 9, 2018, retrieved April 9, 2018

- Podnieks, Andrew (2004), Lord Stanley's Cup, Bolton, Ontario: Fenn Publishing, ISBN 978-1-55168-261-7

- Wong, John (Summer 2006), "From Rat Portage to Kenora: The Death of a (Big-Time) Hockey Dream", Journal of Sport History, 33 (2): 175–191

- Zweig, Eric (2012–2013a), "Au Revoir, Rat Portage: The Early Days of Tommy Phillips", Hockey Research Journal, 16: 9–17

- Zweig, Eric (2006), "Changing Seasons: Accommodating Kenora's Stanley Cup Challenge", Hockey Research Journal, 10: 7–8

- Zweig, Eric (2022), Engraved in History: The Story of the Stanely Cup Champion Kenora Thistles, Kenora, Ontario: Rat Portage Press, ISBN 978-1-7778897-0-8

- Zweig, Eric (2001), "Kenora vs Brandon: The Small Town Series that Disappeared", Hockey Research Journal, 5: 17–20

- Zweig, Eric (2012), Stanley Cup: 120 Years of Hockey Supremacy, Richmond Hill, Ontario: Firefly Books, ISBN 978-1-77085-104-7

- Zweig, Eric (January 15, 2007), "Thistles Still Stick Together", Toronto Star, Toronto, retrieved March 27, 2018