Khasa Kingdom

Khasa-Malla kingdom (Nepali: खस मल्ल राज्य Khasa Malla Rājya), popularly known as Khasa Kingdom (Nepali: खस राज्य Khasa Rājya) and Yatse (Wylie: ya rtse) in Tibetan, was a medieval kingdom from the modern day far-western Nepal and parts of Uttarakhand state in India, established around the 11th century. It was ruled by kings of Khasa tribe who bore the family name "Malla" (not to be confused with the later Malla dynasty of Kathmandu).[2] The Khasa Malla kings ruled western parts of Nepal during 11th–14th century.[3] The 954 AD Khajuraho Inscription of Dhaṇga states Khasa Kingdom equivalent to Gauda of Bengal and Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty.[4]

Khasa Malla Kingdom Nepali: खस मल्ल राज्य | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11th–14th centuries | |||||||||||||||||

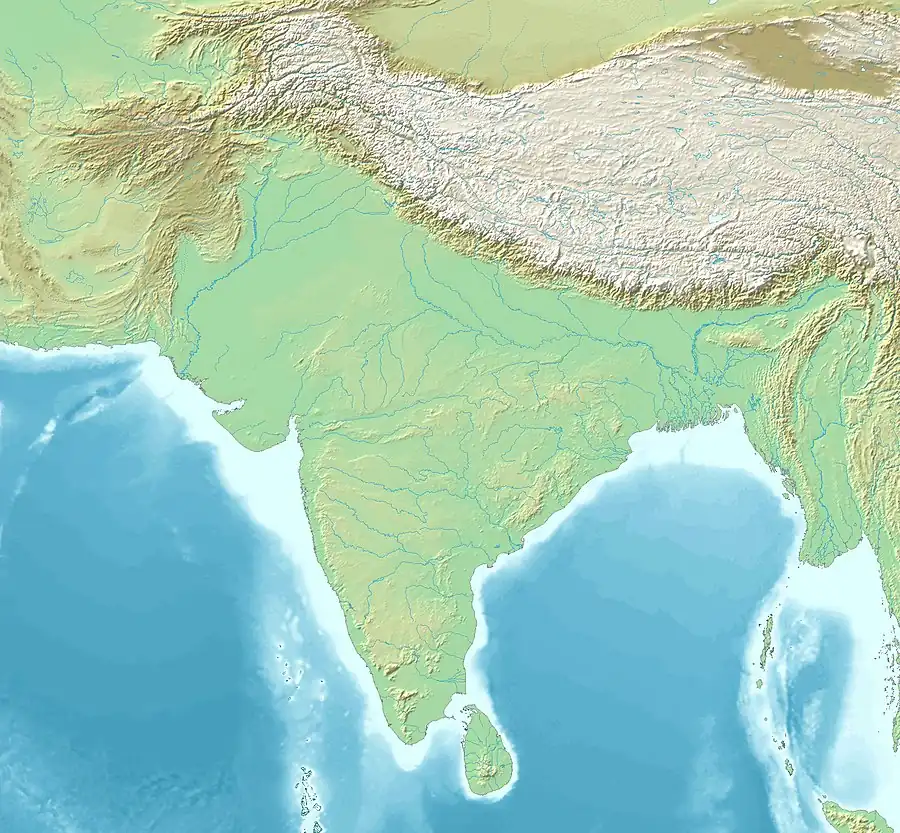

Location of the Sinja Valley, heartland of the Khasa Kingdom, and location of known inscriptions. | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Sinja Valley | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Maharajadhiraja[1] (Sovereign King) | |||||||||||||||||

• c. 11th century | Nāgarāja | ||||||||||||||||

• 1207-1223 | Krachalla Deva | ||||||||||||||||

• 1223–1287 | Ashok Challa | ||||||||||||||||

• | Jitari Malla | ||||||||||||||||

• | Ananda Malla | ||||||||||||||||

• early 14th century | Ripu Malla | ||||||||||||||||

• 14th century | Punya Malla | ||||||||||||||||

• 14th century | Prithvi Malla | ||||||||||||||||

• 14th century | Abhaya Malla | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Established | 11th | ||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 14th centuries | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||

History

An ancient tribe named Khasa is mentioned in several ancient legendary Indian texts, including the Mahabharata. The Khasas are mentioned in several Indian inscriptions dated between 8th and 13th centuries CE.[4] The Khasa Malla kingdom was feudatory and the principalities were independent in nature.[5] Most of its territory was over the Karnali River basin.[5] In the 12th century, King Nāgarāja conquered the principal Jumla Kingdom of the central Himalayas and overran lands up to Bheri River in the east, Satluj River in the west and Mayum pass of Tibet in the north.[6] King Nāgarāja also referred as Jāveśvara (Nepali: जावेश्वर), came from Khāripradeśa (present-day Ngari Province) and set up his capital at Semjā.[7] The Khas dynasties were originated at 11th century or earlier period. There were two dynasties of Khas one at Guge and other at Jumla.[8]

The widely regarded most renowned King of Khasa Malla Kingdom was Prithvi Malla.[7] Prithvi Malla had firmly established the Kingdom around 1413 A.D.[9] The limits of the reign of King Pṛthvīmalla reached the greatest height of the Khas Empire which included Guge, Purang and Nepalese territories up to Dullu in the southwest and Kaskikot in the east.[10] Giuseppe Tucci contends that The Tibetan chronicles show Pṛthvīmalla as the last king of this empire.[11] This kingdom disintegrated after the death of Abhaya Malla and formed the Baise rajya confederacy.[9]

Inscriptions

The earliest Khasa Malla inscription was the copper plate inscription of King Krachalla dated Poush 1145 Shaka Samvat (1223 A.D.) which is in the possession of Baleshwar temple in Sui, Kumaon.[12][1][13] This inscription substantiates that King Krachalla (referred as "Paramabhattaraka Maharajadhiraja Shriman Krachalladeva Narapati") on the 16th year of his reign defeated the kings of Kirtipur or Kartikeyapur (Kumaon) and established his reign there. It was written at "Srisampannanagar" (Srinagar) in Dullu. Thus, this inscription proves that King Krachalla ascended the throne in Dullu on 1207 A.D.[1] Furthermore, Krachalla described himself as a devout Buddhist ('Parama Saugata')[14][13] and is mentioned to have won over "Vijayarajya" (realm of victory) and destroyed the demolished city of Kantipura (Kartikeyapur).[15]

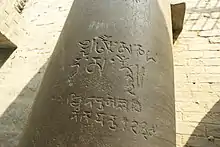

Ashok Challa had issued several inscriptions in modern-day Bodhgaya, Bihar dated 1255 and 1278.[12] In the Bodhgaya copperplate inscription, he refers to himself as "Khasha-Rajadhiraja ("emperor of the Khashas").[16] There are inscriptions of Ripu Malla on the Ashoka Pillar of Lumbini and Nigalihawa; the Lumbini pillar bears the name of his son as Sangrama Malla.[1] Prithvi Malla's stone pillar inscription dated 1279 Shaka Samvat (1357 A.D.) at Dullu discovered by Yogi Naraharinath, contains the names of his predecessors.[17] It further states that the Khasa Malla dynasty was founded six generations before Krachalla by Emperor Nagaraja. The inscription further states that Emperor Nagaraja founded the Khasa Malla capital at Seṃjā (or, Siṃjā, Sijā, Sijjā), near modern Jumla.[12] A gold inscription of Prithvi Malla discovered at Jumla, dated 1278 Shaka Samvat (1356 A.D.) mentions "Buddha, Dharma, Sangha" along with "Brahma, Vishnu, Maheshwara".[14] The inscription of Prithvi Malla on Shitushka in Jumla is quoted as:

Oṃ maṇi padme huṃ. Maṃgalama bhavatu śrīpṛthvīmalladevaḥ likhitama idaṃ puṇyaṃ jagatī sidyasyā[18]

The languages used by Prithvi Malla in his inscription belongs to 13th century form of modern Nepali.[19]

Religion, Language and culture

The language of the Khas Kingdom was Khas language and Sanskrit.[7][21] Some of the earliest Devanagari script examples are the 13th century records from the sites in the former Khasa kingdom. These archaeological sites are located in Jumla, Surkhet and Dailekh districts. Sinja Valley was the ancient capital city and powerful town of the Khas Mallas[22] between 12th and 14th century and the centre of origin of Nepali (Khas) language.[20]

Most of the initial Khas kings before Pṛthvīmalla were Buddhist. Hinduisation of the kingdom began when King Ripumalla commenced the southward expansion of the kingdom and contacts to India slowly increased.[10] King Pṛthvīmalla always used Buddhist syllables in his inscription though he had a strong preference for Hinduism. The Prashasti of Dullu inscription by Pṛthvīmalla shows Buddhist syllables, mantra, and invocations, however, the latter Kanakapatra of Shitushka was fundamentally Hindu. These two inscriptions of King Pṛthvīmalla showed the transition of the state from Buddhism to Hinduism.[24] The reign of King Punya Malla and Prithvi Malla had strict traditional Hindu ritual and customs.[25] A Buddhist-Hindu shrine Kakrebihar has a signboard referring it to the reign of King Ashok Challa but as per experts, it could belong to the reign of King Krachalla.[26]

Rulers

Titles, ranks and suffixes

The successors of King Nāgarāja adhered to some suffix as -illa and -challa like King Chapilla, King Krachalla.[27] Challa and Malla were titles of kings and princes. Rāulā was the title of a high-ranking official. Personalities like Malayavarma, Medinivarma, Samsarivarma, Balirāja,[note 1] etc. had title of Rāulā.[29] Mandalesvara or Mandalik was a title conferred on powerful persons of the Kingdom. Royal princes, senior officials and defeated Kings were appointed to the post of Mandalesvara.[30]

List

The Dullu stone pillar inscription dated 1279 Shaka Samvat (1357 A.D.) of King Prithvi Malla consists the following names of his predecessors:[17] 1. Krachalla 2. Ashokachalla 3. Jitari Malla 4. Akshaya Malla 5. Ashoka Malla 6. Ananda Malla 7. Ripu Malla 8. Sangrama Malla 9. Jitari Malla 10. Aditya Malla

The list of Khas kings mentioned by Giuseppe Tucci is in the following succession up to Prithvi Malla:[31]

- Nāgarāja (Nepali: नागराज);[32][33] also known as Jāveśvara[7] or Nagadeva by Tibetan chronicles including a Chronicle of Fifth Dalai Lama[34]

- Chaap/Cāpa (Nepali: चाप; IAST: Cāpa); son of Nāgarāja[33]

- Chapilla/Cāpilla (Nepali: चापिल्ल; IAST: Cāpilla), son of Cāpa[33]

- Krashichalla (Nepali: क्राशिचल्ल; IAST: Krāśicalla), son of Cāpilla[33]

- Kradhichalla (Nepali: क्राधिचल्ल; IAST: Krādhicalla), son of Krāśicalla[33]

- Krachalla (Nepali: क्राचल्ल; IAST: Krācalla), son of Krādhicalla[33] (1207 CE[1]–1223)

- Ashoka Challa (Nepali: अशोक चल्ल; IAST: Aśokacalla), son of Krācalla[33] (1223–87)

- Jitari Malla (Nepali: जितारी मल्ल; IAST: Jitārimalla), first son of Aśokacalla[35]

- Ananda Malla (Nepali: आनन्द मल्ल; IAST: Ānandamalla), second son of Aśokacalla[35]

- Ripu Malla (Nepali: रिपु मल्ल; IAST: Ripumalla) (1312–13), son of Ānandamalla[35]

- Sangrama Malla (Nepali: संग्राम मल्ल; IAST: Saṃgrāmamalla), son of Ripumalla[35]

- Aditya Malla (Nepali: आदित्य मल्ल; IAST: Ādityamalla), son of Jitārimalla[35]

- Kalyana Malla (Nepali: कल्याण मल्ल; IAST: Kalyāṇamalla), son of either Ādityamalla or Saṃgrāmamalla[35]

- Pratapa Malla (Nepali: प्रताप मल्ल; IAST: Pratāpamalla), son of Kalyāṇamalla, had no scions[35]

- Punya Malla (Nepali: पुण्य मल्ल; IAST: Puṇyamalla)[25] of another Khas family of (Purang royalty)[31]

- Prithvi Malla (Nepali: पृथ्वी मल्ल; IAST: Pṛthvīmalla), son of Puṇyamalla[35]

- Surya Malla (Nepali: सूर्य मल्ल) Son of Ripu Malla, Nāgarāja clan back to rule

- Abhaya Malla (Nepali: अभय मल्ल) (14th century)[9]

Tibetoloical list

The list of rulers of Khasa (Tibetan: Ya rtse) Kingdom established by the Tibetologists Luciano Petech, Roberto Vitali[36] and Giuseppe Tucci are:[31]

- Naga lde (Nepali: Nāgarāja) (early 12th century)

- bTsan phyug lde (Nepali: Cāpilla) (mid-12th century)

- bKra shis lde (Nepali: Krāśicalla) (12th century)

- Grags btsan lde (Nepali: Krādhicalla) (12th century) brother of bTsan phyug lde)

- Grags pa lde (Nepali: Krācalla) (fl. 1225)

- A sog lde (Nepali: Aśokcalla) (fl. 1255–1278) son

- 'Ji dar sMal (Nepali: Jitārimalla) (fl. 1287–1293) son

- A nan sMal (Nepali: Ānandamalla) (late 13th century) brother

- Ri'u sMal (Nepali: Ripumalla) (fl. 1312–1314) son

- San gha sMal (Nepali: Saṃgrāmamalla) (early 14th century) son

- A jid smal (Nepali: Ādityamalla) (1321–1328) son of Jitari Malla

- Ka lan smal (Nepali: Kalyāṇamalla) (14th century)

- Par t'ab smal (Nepali: Pratāpamalla) (14th century)

- Pu ni sMal/Puṇya rMal/bSod nams (Nepali: Puṇyamalla) (fl. 1336–1339) of Purang royalty (another Khas family)

- sPri ti sMal/Pra ti rmal (Nepali: Pṛthvīmalla) (fl. 1354–1358) son

Decline

After the Siege of Chittorgarh in 1303, large immigration of Rajputs occurred into Nepal. Before it, few small groups of Rajputs had been entering into the region from Muslim invasion of India.[5] These immigrants were quickly absorbed into the Khas community due to larger similarities.[5] Historian and Jesuit Ludwig Stiller considers the Rajput interference to the politics of Khas Kingdom of Jumla was responsible for its fragmentation and he explains:

Though they were relatively few in number, they were of higher caste, warriors and of a temperament that quickly gained them the ascendancy in the princedoms in the Jumla Kingdom, their effect on the kingdom was centrifugal.

— Ludwig Stiller's "The Rise of House of Gorkha"[5]

Francis Tucker also further states that "the Rajputs was so often guilty of base ingratitude and treachery to gratify his ambition. They were fierce, ruthless people who would stop at nothing."[5] After the late 13th century the Khas empire collapsed and divided into Baise Rajya (22 principalities) in Karnali-Bheri region and Chaubise rajya (24 principalities) in Gandaki region. [5]

The 22 principalities were

The 24 principalities were

References

Footnotes

- Balirāja went on to become sovereign king of Jumla and founder of Kalyal dynasty.[28]

Notes

- Gnyawali 1971, p. 266.

- Adhikary 1997, p. 37.

- Krishna P. Bhattarai (1 January 2009). Nepal. Infobase Publishing. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-4381-0523-9.

- Thakur 1990, p. 287.

- Pradhan 2012, p. 3.

- Rahul 1978, p. 60.

- Regmi 1965, p. 717.

- Carassco 1959, pp. 14–19.

- Pradhan 2012, p. 21.

- Tucci 1956, p. 109.

- Tucci 1956, p. 112.

- "Ian Alsop: The Metal Sculpture of the Khasa Mallas". Archived from the original on 15 November 2021.

- Regmi 1971, p. 269.

- Gnyawali 1971, p. 267.

- Regmi 1971, pp. 269–271.

- "Nepali language | Britannica".

- Gnyawali 1971, p. 265.

- Tucci 1956, p. 43.

- Gnyawali 1971, pp. 268.

- Sinja valley – UNESCO World Heritage Centre

- Tucci 1956, p. 11.

- Adhikary 1997, p. 76.

- Le Huu Phuoc, Buddhist Architecture, p.269

- Tucci 1956, p. 110.

- Adhikary 1997, p. 81.

- "Buddhist relics in western Nepal – Nepali Times". Archived from the original on 15 November 2021.

- Adhikary 1997, p. 35.

- Adhikary 1997, p. 72.

- Adhikary 1997, p. 89.

- Adhikary 1997, p. 84.

- Tucci 1956, p. 66.

- http://therisingnepal.org.np/news/1783 Archived 27 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Regmi 1965, p. 714.

- Tucci 1956, pp. 54–59.

- Tucci 1956, p. 50.

- L. Petech (1980), 'Ya-ts'e, Gu-ge, Pu-rang: A new study', The Central Asiatic Journal 24, pp. 85–111; R. Vitali (1996), The kingdoms of Gu.ge Pu.hrang. Dharamsala: Tho.ling gtsug.lag.khang.

Books

- Adhikary, Surya Mani (1997). The Khaśa kingdom: a trans-Himalayan empire of the middle age. Nirala. ISBN 978-81-85693-50-7.

- Carassco, Pedro (1959), Land and polity in Tibet, ISBN 0295740833

- Gnyawali, Surya Bikram (1 December 1971) [1962], "The Malla Kings of Western Nepal" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 3 (12): 265–268

- Pradhan, Kumar L. (2012), Thapa Politics in Nepal: With Special Reference to Bhim Sen Thapa, 1806–1839, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, ISBN 9788180698132

- Rahul, Ram (1978). The Himalaya as a frontier. Vikas. ISBN 9780706905649.

- Regmi, D.R. (1965), Medieval Nepal, vol. 1, Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (1 December 1971), "The Baleshwar Inscription of King Krachalla" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 3 (12): 269–272

- Thakur, Laxman S. (1990). K. K. Kusuman (ed.). The Khasas An Early Indian Tribe. pp. 285–293. ISBN 978-81-7099-214-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Tucci, Giuseppe (1956), Preliminary Report on Two Scientific Expeditions in Nepal, David Brown Book Company, ISBN 9788857526843