Kavad I

Kavad I (Middle Persian: 𐭪𐭥𐭠𐭲 Kawād; 473 – 13 September 531) was the Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 488 to 531, with a two or three-year interruption. A son of Peroz I (r. 459–484), he was crowned by the nobles to replace his deposed and unpopular uncle Balash (r. 484–488).

| |

|---|---|

| King of Kings of Iran and non-Iran[lower-alpha 1] | |

.jpg.webp) Plate of a Sasanian king hunting rams, perhaps Kavad I | |

| King of the Sasanian Empire | |

| 1st reign | 488–496 |

| Predecessor | Balash |

| Successor | Jamasp |

| 2nd reign | 498/9–531 |

| Predecessor | Jamasp |

| Successor | Khosrow I |

| Born | 473 |

| Died | 13 September 531 (aged 57–58) |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue | |

| House | House of Sasan |

| Father | Peroz I |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Inheriting a declining empire where the authority and status of the Sasanian kings had largely ended, Kavad tried to reorganize his empire by introducing many reforms whose implementation was completed by his son and successor Khosrow I. They were made possible by Kavad's use of the Mazdakite preacher Mazdak leading to a social revolution that weakened the authority of the nobility and the clergy. Because of this, and the execution of the powerful king-maker Sukhra, Kavad was imprisoned in the Castle of Oblivion ending his reign. He was replaced by his brother Jamasp. However, with the aid of his sister and an officer named Siyawush, Kavad and some of his followers fled east to the territory of the Hephthalite king who provided him with an army. This enabled Kavad to restore himself to the throne in 498/9.

Bankrupted by this hiatus, Kavad applied for subsidies from the Byzantine emperor Anastasius I. The Byzantines had originally paid the Iranians voluntarily to maintain the defense of the Caucasus against attacks from the north. Anastasius refused the subsidies, which led Kavad to invade his domains, thus starting the Anastasian War. Kavad first seized Theodosiopolis and Martyropolis respectively, and then Amida after holding the city under siege for three months. The two empires made peace in 506, with the Byzantines agreeing to pay subsidies to Kavad for the maintenance of the fortifications on the Caucasus in return for Amida. Around this time, Kavad also fought a lengthy war against his former allies, the Hephthalites; by 513 he had re-taken the region of Khorasan from them.

In 528, war between the Sasanians and Byzantines erupted again, because of the Byzantines refusal to acknowledge Khosrow as Kavad's heir, and a dispute over Lazica. Although Kavad's forces suffered two notable losses at Dara and Satala, the war was largely indecisive, with both sides suffering heavy losses. In 531, while the Iranian army was besieging Martyropolis, Kavad died from an illness. He was succeeded by Khosrow I, who inherited a reinvigorated and mighty empire that equaled that of the Byzantines.

Because of the many challenges and issues Kavad successfully overcame, he is considered one of the most effective and successful kings to rule the Sasanian Empire. In the words of the Iranologist Nikolaus Schindel, he was "a genius in his own right, even if of a somewhat Machiavellian type."

Name

Due to increased Sasanian interest in Kayanian history, Kavad was named after the mythological Kayanian king Kavi Kavata.[1] The name is transliterated in Greek as Kabates,[2] Chü-he-to in Chinese,[3] and Qubādh in Arabic.[2]

Background and state of Sasanian Iran

The son of the Sasanian shah Peroz I (r. 459–484), Kavad was born in 473.[4][lower-alpha 2] The Sasanian family had been the monarchs of Iran since 224 after the triumph of the first Sasanian shah Ardashir I (r. 224–242) over the Parthian (Arsacid) Empire.[5] Although Iranian society was greatly militarised and its elite designated themselves as a "warrior nobility" (arteshtaran), it still had a significantly smaller population, was more impoverished, and was a less centralized state compared to the Roman Empire.[5] As a result, the Sasanian shahs had access to fewer full-time fighters, and depended on recruits from the nobility instead.[5] Some exceptions were the royal cavalry bodyguard, garrison soldiers, and units recruited from places outside Iran.[5]

The bulk of the high nobility included the powerful Parthian noble families (known as the wuzurgan) that were centered on the Iranian plateau.[6] They served as the backbone of the Sasanian feudal army and were largely autonomous.[6] The Sasanian shahs had noticeably little control over the wuzurgan; attempts to restrict their self-determination usually resulted in the murder of the shah.[7] Ultimately, the Parthian nobility worked for the Sasanian shah for personal benefit, personal oath, and, conceivably, a common awareness of the "Aryan" (Iranian) kinship they shared with their Persian overlords.[6]

Another vital component of the army was the Armenian cavalry, which was recruited from outside the ranks of the Parthian wuzurgan.[8] However, the revolt of Armenia in 451 and the loss of its cavalry had weakened the Sasanian's attempts to keep the Hunnic tribes (i.e. the Hephthalites, Kidarites, Chionites and Alkhans)[9] of the northeastern border in check.[10][11][lower-alpha 3] Indeed, Kavad's grandfather Yazdegerd II (r. 438–457) had managed to hold off the Kidarites during his wars against them, which had occupied him throughout most of his reign.[11][12][13] Now, however, Sasanian authority in Central Asia began to decay.[11]

In 474 and the late 470s/early 480s, Peroz was defeated and captured twice by the Hephthalites respectively.[14][15] In his second defeat, he offered to pay thirty mule packs of silver drachms in ransom, but could only pay twenty. Unable to pay the other ten, he sent Kavad in 482 as a hostage to the Hephthalite court until he could pay the rest.[14][16][17] He eventually managed to gain the ten mule packs of silver by imposing a poll-tax on his subjects, and thus secured the release of Kavad before he mounted his third campaign in 484.[17] There, Peroz was defeated and killed by a Hephthalite army, possibly near Balkh.[10][4][18] His army was completely destroyed, and his body was never found.[19] Four of his sons and brothers had also died.[14] The main Sasanian cities of the eastern region of Khorasan−Nishapur, Herat and Marw were now under Hephthalite rule.[4]

Sukhra, a member of the Parthian House of Karen, one of the Seven Great Houses of Iran, quickly raised a new force and stopped the Hephthalites from achieving further success.[20] Peroz' brother, Balash, was elected as shah by the Iranian magnates, most notably Sukhra and the Mihranid general Shapur Mihran.[21] However, Balash proved unpopular among the nobility and clergy who had him blinded and deposed after just four years in 488.[22][23] Sukhra, who had played a key role in Balash's deposition,[22] appointed Kavad as the new shah of Iran.[24] According to Miskawayh (d. 1030), Sukhra was Kavad's maternal uncle.[4]

First reign

Accession and conditions of the empire

Kavad ascended the throne in 488 at the age of 15. His youth is emphasized on his coins, which show him with short whiskers.[4] He inherited an empire that had reached its lowest ebb. The nobility and clergy exerted great influence and authority over the nation, and were able to act as king-makers, as seen by their choice to depose Balash.[25] Economically, the empire was not doing well either, the result of drought, famine, and the crushing defeats delivered by the Hephthalites. They had not only seized large parts of its eastern provinces, but had also forced the Sasanians to pay vast amounts of tribute to them, which had depleted the royal treasury of the shah.[26][27][28] Rebellions were occurring in the western provinces including Armenia and Iberia.[26][29] Simultaneously, the country's peasant class was growing more and more uneasy and alienated from the elite.[29]

Conflict with Sukhra over the empire

.png.webp)

The young and inexperienced Kavad was tutored by Sukhra during his first five years as shah.[4] During this period, Kavad was a mere figurehead, whilst Sukhra was the de facto ruler of the empire. This is emphasized by al-Tabari, who states that Sukhra "was in charge of government of the kingdom and the management of affairs ... [T]he people came to Sukhra and undertook all their dealings with him, treating Kavad as a person of no importance and regarding his commands with contempt."[24] Numerous regions and the representatives of the elite paid tribute to Sukhra not to Kavad.[30] Sukhra controlled the royal treasury and the Iranian military.[30] In 493, Kavad, having reached adulthood, wanted to put an end to Sukhra's dominance, and had him exiled to his native Shiraz in southwestern Iran.[4][30] Even in exile, however, Sukhra was in control of everything except the kingly crown.[30] He bragged about having put Kavad on the throne.[30]

Alarmed by the thought that Sukhra might rebel, Kavad wanted to get rid of him completely. He lacked the manpower to do so, however, as the army was controlled by Sukhra and the Sasanians relied mainly on the military of the Seven Great Houses of Iran.[31] He found his solution in Shapur of Ray, a powerful nobleman from the House of Mihran, and a resolute opponent of Sukhra.[32] Shapur, at the head of an army of his own men and disgruntled nobles, marched to Shiraz, defeated Sukhra's forces, and imprisoned him in the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon.[33] Even in prison, Sukhra was considered too powerful and was executed.[33] This caused displeasure among some prominent members of the nobility weakening Kavad's status as shah.[34] It also marked the temporary loss of authority of the House of Karen, whose members were exiled in the regions of Tabaristan and Zabulistan, which was away from the Sasanian court in Ctesiphon.[35][lower-alpha 4]

The Mazdakite movement and Kavad I's deposition

Not long after Sukhra's execution, a Zoroastrian priest named Mazdak caught Kavad's attention. Mazdak was the chief representative of a religious and philosophical movement called Mazdakism. Not only did it consist of theological teachings, it also advocated for political and social reforms, which would impact the nobility and clergy.[36][37] The Mazdak movement was against violence and called for the sharing of wealth, women and property,[27] an archaic form of communism.[34] According to modern historians Touraj Daryaee and Matthew Canepa, sharing women was most likely an overstatement and defamation deriving from Mazdak's decree that loosened marriage rules to help the lower classes.[37] Powerful families saw this as a tactic to weaken their lineage and advantages, which was most likely the case.[37] Kavad used the movement as a political tool to curb the power of the nobility and clergy.[34][27] Royal granaries were distributed, and land was shared among the lower-classes.[36]

The historicity of the persona of Mazdak has been questioned.[21] He may have been a fabrication to take blame away from Kavad.[38] Contemporary historians, including Procopius and Joshua the Stylite make no mention of Mazdak naming Kavad as the figure behind the movement.[38] Mention of Mazdak only emerges in later Middle Persian Zoroastrian documents, namely the Bundahishn, the Denkard, and the Zand-i Wahman yasn.[38] Later Islamic-era sources, particularly al-Tabari's work, also mention Mazdak.[38] These later writings were perhaps corrupted by Iranian oral folklore, given that blame put on Mazdak for the redistribution of aristocratic properties to the people, is a topic repeated in Iranian oral history.[38] Other "villains" in Iranian history, namely Gaumata in the Behistun Inscription of the Achaemenid ruler Darius the Great (r. 522 – 486 BC), and Wahnam in the Paikuli inscription of the Sasanian shah Narseh (r. 293–302), are frequently accused of similar misdeeds.[38] Regardless of the main figure behind this movement, the nobility deposed Kavad in 496. They installed his more impressionable brother Jamasp on the throne.[39][40] One of the other reasons behind Kavad's deposal was his execution of Sukhra.[4] Meanwhile, chaos was occurring in the country, notably in Mesopotamia.[40]

Imprisonment, flight and return

A council soon took place among the nobility to discuss what to do with Kavad. Gushnaspdad, a member of a prominent family of landowners (the Kanarangiyan) proposed that Kavad be executed. His suggestion was overruled, however, and Kavad was imprisoned instead in the Prison of Oblivion in Khuzestan.[41][39] According to Procopius' account, Kavad's wife approached the commander of the prison. They came to an understanding that she would be allowed to see Kavad in exchange for sleeping with him.[42] Kavad's friend, Siyawush, who was regularly in the same area as the prison, planned his friend's escape by preparing horses near the prison.[42] Kavad changed clothes with his wife to disguise himself as a female, and escaped from the prison and fled with Siyawush.[42]

Al-Tabari's account is different. He says that Kavad's sister helped him to escape by rolling him in a carpet, which she made the guard believe was soaked with her menstrual blood.[43] The guard did not object or investigate the carpet, "fearing lest he become polluted by it".[43] One of the authors of the Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, John Robert Martindale, proposes she may have in fact been Sambice, Kavad's sister-wife, who was the mother of his eldest son, Kawus.[44] Regardless, Kavad managed to escape imprisonment, and fled to the court of the Hephthalite king, where he took refuge.[42][39] According to the narratives included in the history of al-Tabari, during his flight Kavad met a peasant girl from Nishapur, named Niwandukht, who became pregnant with his child, who would later be Khosrow I.[45][lower-alpha 5] However, the story has been dismissed as "fable" by the Iranologist Ehsan Yarshater.[48] Khosrow's mother was in reality a noblewoman from the Ispahbudhan clan, one of the Seven Great Houses of Iran.[49] At the Hephthalite court, Kavad gained the support of the Hephthalite king, and also married his daughter (who was Kavad's niece).[4]

During his stay at the Hephthalite court, Kavad might have witnessed the rise of the Hephthalites to a better position than that of their former suzerains, the Kidarites.[50] The present-day district of Qobadian (the Arabicized form of Kavadian) near Balkh, which was then under Hephthalite rule, was perhaps founded by Kavad, and possibly served as his source of revenue.[51] In 498 (or 499), Kavad returned to Iran with a Hephthalite army.[52][4] When he crossed the domains of the Kanarangiyan family in Khorasan, he was met by Adergoudounbades, a member of the family, who agreed to help him.[41] Another noble who supported Kavad was Zarmihr Karen, a son of Sukhra.[4]

Jamasp and the nobility and clergy did not resist as they wanted to prevent another civil war.[53] They came to an agreement with Kavad that he would be shah again with the understanding that he would not hurt Jamasp or the elite.[53] Jamasp was spared, albeit probably blinded, while Gushnaspdad and other nobles who had plotted against Kavad were executed.[4] Generally, however, Kavad secured his position by lenience.[34] Adergoudounbades was appointed the new head of the Kanarangiyan,[54] while Siyawush was appointed the head of the Sasanian army (arteshtaran-salar).[42] Another of Sukhra's sons, Bozorgmehr, was made Kavad's minister (wuzurg framadār).[53] Kavad's reclamation of his throne displays the troubled circumstances of the empire, where in a time of anarchy a small force was able to overwhelm the nobility-clergy alliance.[39]

Second reign

Reforms

Right: The "Kulagysh plate", Sasanian silver bowl, showing a battle scene between two knights. 6th-7th Century.

Kavad's reign is noteworthy for his reforms, which he had been able to make with the nobility and clergy weakened by the Mazdakites. They would not be completed under his reign but were continued by his son, Khosrow I.[4][55] The serious blows the Sasanians had suffered at the hands of the Hephthalites in the last quarter of the 5th-century was a key reason behind the reforms the two made.[56] Tax reform was implemented, a poll tax was created, and a review of taxable land was undertaken to ensure taxation was fair.[57] The empire was divided into four frontier regions (kust in Middle Persian), with a military commander (spahbed) in charge of each district; a chancery was also added to keep the soldiers equipped.[57][58] Before Kavad and Khosrow's reforms, the Iranians' general (Eran-spahbed) managed the empire's army.[59] Many of these military commanders were notably from the Parthian wuzurgan, indicating the continuation of their authority, despite the efforts by Kavad and Khosrow.[8] A new priestly office was also created known as the "advocate and judge of the poor" (driyōšān jādag-gōw ud dādwar), which assisted the clergy to help the poor and underprivileged (an obligation they had possibly ignored previously).[60][57]

The power of the dehqan, a class of small land-owning magnates, increased substantially (and possibly even led to their establishment in the first place).[57] A group of these dehqans was enlisted into a group of cavalry men, who were managed directly by the shah and earned steady wages.[4] This was done to decrease the reliance on the Parthian cavalry.[61] Soldiers were also enlisted from Sasanian allies, such as the Hephthalites, Arabs, and Daylamites.[61] As a result, the newly rejuvenated Sasanian army proved successful in its efforts in subsequent decades. It sacked the Byzantine city of Antioch in 540, conquered Yemen in the 570s, and under the Parthian military commander Bahram Chobin defeated both the Hephthalites and Western Turkic Khaganate in the late 580s.[8]

Although the reforms were beneficial for the Sasanian Empire, they may also have resulted in the decline of the traditional links between the aristocracy and the crown under Hormizd IV (r. 579–590) and Khosrow II (r. 590–628), to the degree that many belonging to the wuzurgan class—notably Bahram Chobin of the Mihran family, and later Shahrbaraz of the same family—were bold enough to dispute the legitimacy of the Sasanian family and lay claims to the throne.[62]

Persecution of Mazdak and his followers

With his reforms under way by the 520s, Kavad no longer had any use for Mazdak,[57] and he officially stopped supporting the Mazdakites.[4] A debate was arranged where not only the Zoroastrian priesthood, but also Christian and Jewish leaders slandered Mazdak and his followers.[57] According to the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings), written several centuries later by the medieval Persian poet Ferdowsi, Kavad had Mazdak and his supporters sent to Khosrow. His supporters were killed in a walled orchard buried head first with only their feet visible.[57] Khosrow then summoned Mazdak to look at his garden, saying: "You will find trees there that no-one has ever seen and no-one ever heard of even from the mouth of the ancient sages."[57] Mazdak, seeing his followers' corpses, screamed and passed out. He was executed afterwards by Khosrow, who had his feet fastened on a gallows, and had his men shoot arrows at Mazdak.[57] (The validity of the story is uncertain; Ferdowsi used much earlier reports of events to write the Shahnameh, and thus the story may report some form of contemporary memory.[63])

Building projects

Many places were founded or re-built under Kavad. He is said to have founded the city Eran-asan-kerd-Kawad in Media;[4] Fahraj in Spahan;[64] and Weh-Kawad, Eran-win(n)ard-Kawad, Kawad-khwarrah, and Arrajan in Pars.[4][65] He rebuilt Kirmanshah in Media, which he also used as one of his residences.[66] He is also said to have founded a township in Meybod, which was named Haft-adhar ("seven fires"), because of a Zoroastrian fire temple being established there. Its original fire was created by fire brought from seven other temples in Pars, Balkh, Adurbadagan, Nisa, Spahan, Ghazni, and Ctesiphon.[67]

In the Caucasus, Kavad had new fortifications built at Derbent,[68] and ordered the construction of the Apzut Kawat wall (Middle Persian: *Abzūd Kawād, "Kavad increased [in glory]" or "has prospered").[69] The prominent Caucasian Albanian capital of P'artaw, which had been rebuilt during the reign of Peroz I and named Perozabad ("the city of Peroz"), was fortified by Kavad and called Perozkavad ("victorious Kavad").[70] The Albanian former capital of Kabala, a large urban area that included the headquarters of one of the Albanian bishops, was also fortified by Kavad.[71] He founded the city of Baylakan, which by most researchers is identified with the ruins of Oren-kala.[72] Ultimately, these extensive buildings and fortifications transformed Caucasian Albania into a bastion of Iranian presence in the Caucasus.[73]

The India trade

The Sasanians exerted considerable influence on trade in the region under Kavad.[74] By using the strategic location of the Persian Gulf, the Sasanians interfered to prevent Byzantine traders from taking take part in the India trade. They accomplished this either by bargaining with trade associates in the Indian subcontinent—ranging from the Gupta Empire in the north to the Anuradhapura monarchs of Sri Lanka in the south—or by attacking the Byzantine boats.[74] Iranian traders were also able to seize Indian vessels well before they could make contact with Byzantine traders.[74] These advantages resulted in the Iranian traders establishing something resembling a monopoly over the India trade.[75]

Anastasian war

The Sasanians and Byzantines had kept peace since the brief Byzantine–Sasanian War of 440. The last major war between the two empires had been during the reign of Shapur II (r. 309–379).[76] However, war finally erupted in 502. Bankrupted by his hiatus in 496–498/9, Kavad applied for subsidies to the Byzantine Empire, who originally had paid the Iranians voluntarily to maintain the defense of the Caucasus against attacks from the north.[77] The Iranians seemingly saw the money as a debt due to them.[77] But now Emperor Anastasius I (r. 491–518) refused subsidies forcing Kavad to attempt to obtain the money by force.[78] In 502, Kavad invaded Byzantine Armenia with a force that included Hephthalite soldiers.[21] He captured Theodosiopolis, perhaps with local support; in any case, the city was undefended by troops and weakly fortified.[78]

He then marched through southwestern Armenia, reportedly without facing any resistance, and entrusted local governor with the administration of the area.[79] He proceeded to cross the Armenian Taurus, and reached Martyropolis, where its governor Theodore, surrendered without any resistance and gave Kavad two years worth of taxes collected from the province of Sophene.[80][81] Because of this, Kavad let Theodore keep his position as governor of the city.[81] Kavad then besieged the fortress-city of Amida through the autumn and winter (502–503). The siege proved to be a far more difficult enterprise than Kavad had expected; the defenders, although unsupported by troops, repelled the Iranian assaults for three months before they were finally defeated.[81]

He had its inhabitants deported to a city in southern Iran, which he named "Kavad's Better Amida" (Weh-az-Amid-Kawad). He left a garrison in Amida which included his general Glon, two marzbans (margraves) and 3,000 soldiers.[82] The Byzantines failed in their attempt to recapture the city. Kavad then tried unsuccessfully to capture Edessa in Osroene.[83] In 505 an invasion of Armenia by the Huns from the Caucasus led to an armistice; the Byzantines paid subsidies to the Iranians for the maintenance of the fortifications on the Caucasus,[84] in return for Amida.[4] The peace treaty was signed by the Ispahbudhan aristocrat Bawi, Kavad's brother-in-law.[85] Although Kavad's first war with the Byzantines did not end with a decisive winner, the conquest of Amida was the greatest accomplishment achieved by a Sasanian force since 359, when the same city had been captured by Shapur II.[4]

Relations with Christianity

Kavad's relationship with his Christian subjects is unclear. In Christian Iberia, where the Sasanians had earlier tried to spread Zoroastrianism, Kavad represented himself as an advocate of orthodox Zoroastrianism. In Armenia, however, he settled disputes with the Christians and appears to have continued Balash's peaceful approach. The Christians of Mesopotamia and Iran proper practised their religion without any persecution, despite the punishment of Christians in Iran proper being briefly mentioned in c. 512/3. Like Jamasp, Kavad also supported the patriarch of the Church of the East, Babai, and Christians served in high offices at the Sasanian court.[4] According to Eberhard Sauer, Sasanian monarchs only persecuted other religions when it was in their urgent political interests to do so.[86]

According to the Chronicle of Seert and the historian Mari ibn Sulayman, Kavad ordered all the religious communities in the empire to submit written descriptions of their beliefs. This took place sometime before 496. In response to this command, the Patriarch Aqaq commissioned Elishaʿ bar Quzbaye, interpreter of the school of Nisibis, to write for the Church of the East. His work was then translated from Syriac to Persian and presented to Kavad. This work has since been lost.[87]

Kavad's reign marked a new turn in Sasanian–Christian relations; before his reign, Jesus had been seen solely as the defender of the Byzantines.[88] This changed under Kavad. According to an apocryphal account in the Chronicle of Pseudo–Zachariah of Mytilene, written by a West Syrian monk at Amida in 569, Kavad saw a vision of Jesus whilst besieging Amida, which encouraged him to remain resolute in his effort.[88] Jesus guaranteed to give him Amida within three days, which happened.[88] Kavad's forces then sacked the city, taking much booty.[88] The city's church was spared, however, due to the relationship between Kavad and Jesus.[88] Kavad was even thought to have venerated a figure of Jesus.[88] According to modern historian Richard Payne, the Sasanians could now be viewed as adherents of Jesus and his saints, if not Christianity itself.[88]

Wars in the east

Not much is known about Kavad's wars in the east. According to Procopius, Kavad was forced to leave for the eastern frontier in 503 to deal with an attack by "hostile Huns", one of the many clashes in a reportedly lengthy war. After the Sasanian disaster in 484, all of Khorasan was seized by the Hephthalites; no Sasanian coins minted in the area (Nishapur, Herat, Marw) have been found from his first reign.[4] The increase in the number of coins minted at Gorgan (which was now the northernmost Sasanian point) during his first reign may indicate a yearly tribute he paid to the Hephthalites.[89] During his second reign, his fortunes changed. A Sasanian campaign in 508 led to the conquest of the Zundaber (Zumdaber) Castellum, associated with the temple of az-Zunin in the area of ad-Dawar, situated between Bust and Kandahar.[90] A Sasanian coin dating to 512/3 has been found in Marw. This indicates the Sasanians under Kavad had managed to re-conquer Khorasan after successfully dealing with the Hephthalites.[4]

Negotiations with the Byzantines over the adoption of Khosrow

Around 520 to secure the succession of his youngest son Khosrow, whose position was threatened by rival brothers and the Mazdakite sect, and to improve his relationship with the Byzantine emperor Justin I, Kavad proposed that he adopt Khosrow.[91] This proposal was greeted initially with enthusiasm by the Byzantine emperor and his nephew, Justinian. However, Justinian's quaestor, Proclus, opposed the move concerned over the possibility that Khosrow might attempt to take over the Byzantine throne.[4] The Byzantines made a counter-proposal to adopt Khosrow not as a Roman but as a barbarian.[92] In the end the negotiations did not reach a consensus. Khosrow reportedly felt insulted by the Byzantines, and his attitude towards them deteriorated.[4]

Mahbod, who with Siyawush, had acted as the diplomats in the negotiations accused him of purposely sabotaging them.[92] Further accusations were made against Siyawush, which included his reverence for new deities, and having his dead wife buried, a violation of Iranian law. Siyawush was thus most likely a Mazdakite, the religious sect that Kavad had originally, but now no longer, supported. Although Siyawush was a close friend of Kavad and had helped him escape imprisonment, Kavad did not try to prevent his execution. Seemingly his purpose was to restrict Siyawush's immense authority as the head of the Sasanian army, a post which was disliked by the other nobles.[4] Siyawush was executed, and his office was abolished.[93] Despite the breakdown of the negotiations, it was not until 530 that full-scale warfare on the main western frontier broke out. In the intervening years, the two sides preferred waging war by proxy, through Arab allies in the south and Huns in the north.[94]

Iberian war

Hostility between the two powers erupted into conflict once again in 528, just a year after the new Byzantine emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565) had been crowned. This was supposedly the result of the Byzantines not acknowledging Khosrow as Kavad's heir. According to the Greek chronicler John Malalas, military clashes first took place in Lazica, which had been disputed between the two empires since 522. Not long after this the battles also spread down to Mesopotamia, where the Byzantines suffered a heavy defeat near the border. In 530, one of the famous open-field battles took place between the Byzantine and Sasanian troops at Dara.[4]

The Sasanian army led by Perozes, Pityaxes and Baresmanas suffered a severe defeat. The battle did not, however, bring an end to the conflict.[4] The following year Kavad raised an army, which he sent under Azarethes to invade the Byzantine province of Commagene.[95] When the Byzantine army under Belisarius approached, Azarethes and his men withdrew east, halting at Callinicum.[95] In the ensuing battle the Byzantines suffered a heavy defeat, but Iranian losses were so great Kavad was displeased with Azarethes, and relieved him of his command.[95][96] In 531, the Iranians besieged Martyropolis. During the siege, however, Kavad became ill and died on 13 September.[97][4] As a result, the siege was lifted and peace was made between Kavad's successor Khosrow I and Justinian.[4]

Coins

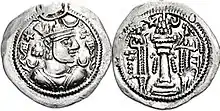

The provinces of Gorgan, Khuzestan, and Asoristan provided the most Sasanian coinage for Kavad during his reign.[98] His reign marks the introduction of distinctive traits on the obverse sides of the coin which includes astral symbols, particularly, a crescent on both of his shoulders, and a star in the left corner.[98] The reverse side shows the traditional fire altar flanked by two attendants facing it in veneration.[98] Kavad used the title of kay (Kayanian) on his coins,[98] a title that had been used since the reign of his grandfather Yazdegerd II (r. 438–457).[13] Kavad was, however, the last Sasanian shah to have kay inscribed on his coins—the last one issued in 513.[98] The regular obverse inscription on his coins simply has his name; in 504, however, the slogan abzōn ("may he prosper/increase") was added.[98][99]

Succession

According to Procopius and other historians, Kavad had written a succession plan that favoured Khosrow just before his death. Historian John Malalas stated that Kavad crowned Khosrow himself.[100] However, at the beginning of Khosrow's reign in 531, Bawi, and other members of the Iranian aristocracy, became involved in a conspiracy to overthrow Khosrow and make Kavad, the son of Kavad's second eldest son Jamasp, the shah of Iran.[101] Upon learning of the plot, Khosrow executed all of his brothers and their offspring, as well as Bawi and the other nobles who were involved.[85]

Khosrow also ordered the execution of Kavad, who was still a child, and was away from the court, being raised by Adergoudounbades. He sent orders to kill Kavad, but Adergoudounbades disobeyed and secretly raised him until he was betrayed to the shah in 541 by his own son, Bahram. Khosrow had him executed, but Kavad, or someone claiming to be him, managed to flee to the Byzantine Empire.[102]

Legacy

Kavad's reign is considered a turning point in Sasanian history.[4] As a result of the many challenges and issues Kavad successfully handled, he is considered one of the most effective and successful kings to rule the Sasanian Empire.[4] In the words of Iranologist Nikolaus Schindel he was "a genius in his own right, even if of a somewhat Machiavellian type."[4] He was successful in his efforts to reinvigorate his declining empire paving the way for a smooth transition to his son Khosrow I, who inherited a powerful empire. He improved it further during his reign, becoming one of the most popular shahs of Iran earning the epithet Anushirvan ("the immortal soul").[103]

The Ziyarid dynasty, which mainly ruled over Tabaristan and Gorgan between 931–1090, claimed that the founder of the dynasty, Mardavij (r. 930–935), was descended from Kavad.[104][105]

Family tree

|

King of Kings | ||||||

| Yazdegerd II[21] (r. 438–457) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hormizd III[21] (r. 457–459) | Peroz I[21] (457–484) | Balash[21] (r. 484–488) | Zarer[21] (d. 485) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Balendukht[106] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kavad I (r. 488–496, 498/9–531) | Jamasp[21] (r. 496–498/9) | Perozdukht[107] | Sambice[44] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kawus[21] (d. c. 531) | Jamasp[108] (d. c. 532) | Xerxes[109] | Khosrow I[21] (r. 531–579) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Also spelled "King of Kings of Iranians and non-Iranians".

- According to Greek chronicler John Malalas, Kavad died at the age of 82, whilst the medieval Persian poet Ferdowsi states that he died at 80, which would put his year of birth sometime in 449-451.[4] The Greek historian Procopius states that Kavad was not old enough to take part in Peroz I's Hephthalite war in 484, and describes him as being around the age of 14-16. This also corresponds with account of the 9th-century Muslim historian Abu Hanifa Dinawari, who stated that Kavad was 15 years-old when he became shah.[4] Sasanian coinage portray Kavad as a young man during his first reign, with short whiskers and no moustache.[4] This is unusual, since Sasanian shahs are generally bearded on their coinage. Besides Kavad, the only Sasanian shahs not to have a bearded portrait are the child-rulers Ardashir III (r. 628–630) and Khosrow III (r. 630–630).[4] This implies that Kavad most likely ascended the throne at a rather young age, which puts his birth in 473.[4]

- Armenian soldiers, however, would serve the Sasanians again in the 6th and 7th-centuries.[10]

- Although some of Sukhra's sons would later serve Kavad, the power of the Karens was first restored during the reign of Kavad's son and successor, Khosrow I Anushirvan (r. 531–579), who reportedly regretted Kavad's approach to the family, and gave them the post of military commander (spahbed) of Khorasan.[35]

- Although al-Tabari places this event before Kavad's first reign, modern scholars agree that it took place in the interlude before his second reign.[46][47]

References

- Boyce 2001, p. 127.

- Bosworth 1999, p. 128 (note #329).

- Pulleyblank 1991, pp. 424–431.

- Schindel 2013a, pp. 136–141.

- McDonough 2013, p. 603.

- McDonough 2013, p. 604.

- McDonough 2013, p. 604 (see also note 3).

- McDonough 2011, p. 307.

- Rezakhani 2017, pp. 85–87.

- McDonough 2011, p. 305.

- McDonough 2013, p. 613.

- Daryaee 2014, p. 23.

- Daryaee.

- Potts 2018, p. 295.

- Bonner 2020, pp. 136–137.

- Rezakhani 2017, p. 127.

- Bonner 2020, p. 137.

- Schippmann 1999, pp. 631–632.

- Payne 2015b, p. 287.

- Payne 2015b, p. 288.

- Shahbazi 2005.

- Chaumont & Schippmann 1988, pp. 574–580.

- Bonner 2020, p. 139.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 78.

- Daryaee 2014, pp. 25–26.

- Axworthy 2008, p. 58.

- Daryaee 2014, p. 26.

- Daryaee & Rezakhani 2016, p. 50.

- Kia 2016, p. 253.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 79.

- Pourshariati 2008, pp. 79–80.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 80.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 81.

- Frye 1983, p. 150.

- Pourshariati 2017.

- Daryaee 2014, pp. 26–27.

- Daryaee & Canepa 2018.

- Shayegan 2017, p. 809.

- Daryaee 2014, p. 27.

- Axworthy 2008, p. 59.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 267.

- Procopius, VI.

- Bosworth 1999, p. 135.

- Martindale 1980, pp. 974–975.

- Bosworth 1999, p. 128.

- Kia 2016, p. 257.

- Rezakhani 2017, p. 133 (note 22).

- Bosworth 1999, p. p. 128 (note 330).

- Bosworth 1999, p. 128 (note 330); Rezakhani 2017, p. 133 (note 22); Martindale 1992, pp. 381–382; Pourshariati 2008, pp. 110–111

- Rezakhani 2017, p. 133.

- Rezakhani 2017, p. 133 (note 23).

- Rezakhani 2017, p. 131.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 114.

- Pourshariati 2008, pp. 267–268.

- Axworthy 2008, pp. 59–60.

- Daryaee & Rezakhani 2017, p. 209.

- Axworthy 2008, p. 60.

- Miri 2012, p. 24.

- Daryaee 2014, p. 124.

- Daryaee 2014, pp. 129–130.

- McDonough 2011, p. 306.

- Shayegan 2017, p. 811.

- Axworthy 2008, p. 61.

- Langarudi 2002.

- Gaube 1986, pp. 519–520.

- Calmard 1988, pp. 319–324.

- Modarres.

- Kettenhofen 1994, pp. 13–19.

- Gadjiev 2017a.

- Chaumont 1985, pp. 806–810.

- Gadjiev 2017b, pp. 124–125.

- Gadjiev 2017b, pp. 125.

- Gadjiev 2017b, pp. 128–129.

- Sauer 2017, p. 294.

- Sauer 2017, p. 295.

- Daryaee 2009.

- Daryaee & Nicholson 2018.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 62.

- Howard-Johnston 2013, p. 872.

- Howard-Johnston 2013, pp. 872–873.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 63.

- Bonner 2020, p. 156 (see also note 184).

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 69–71.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 77.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 111.

- Sauer 2017, p. 190.

- Võõbus 1965, pp. 126–127.

- Payne 2015a, p. 171.

- Potts 2018, pp. 296–297.

- Potts 2018, p. 297.

- Schindel 2013a, pp. 136–141; Kia 2016, p. 254

- Procopius, XI.

- Sundermann 1986, p. 662.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 81–82.

- Martindale 1992, p. 160.

- Procopius, Book I.xviii.

- Procopius Book I.xxi.

- Schindel 2013b, pp. 141–143.

- Schindel 2013c, p. 837.

- Crone 1991, p. 32.

- Frye 1983, p. 465

- Martindale 1992, pp. 16, 276; Pourshariati 2008, pp. 268–269; Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 112.

- Kia 2016, pp. 256–257, 261; Schindel 2013a, pp. 136–141; Daryaee 2014, pp. 28–30

- Curtis & Stewart 2009, p. 38.

- Spuler 2014, pp. 344–345.

- Toumanoff 1969, p. 28.

- Rezakhani 2017, p. 128.

- Martindale 1980, p. 1995.

- Shahîd 1995, p. 76.

Bibliography

Ancient works

- Procopius, History of the Wars.

Modern works

- Bosworth, C. E., ed. (1999). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume V: The Sāsānids, the Byzantines, the Lakhmids, and Yemen. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4355-2.

- Axworthy, Michael (2008). A History of Iran: Empire of the Mind. New York: Basic Books. pp. 1–368. ISBN 978-0-465-00888-9.

- Bonner, Michael (2020). The Last Empire of Iran. New York: Gorgias Press. pp. 1–406. ISBN 978-1463206161.

- Boyce, Mary (2001). Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Psychology Press. pp. 1–252. ISBN 9780415239028.

- Calmard, Jean (1988). "Kermanshah iv. History to 1953". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XVI, Fasc. 3. pp. 319–324.

- Chaumont, M. L. (1985). "Albania". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 8. pp. 806–810.

- Chaumont, M. L.; Schippmann, K. (1988). "Balāš, Sasanian king of kings". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 6. pp. 574–580.

- Crone, Patricia (1991). "Kavād's Heresy and Mazdak's Revolt". Iran. 29: 21–42. doi:10.2307/4299846. JSTOR 4299846. (registration required)

- Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Stewart, Sarah (2009). The Rise of Islam: The Idea of Iran Vol 4. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1845116910.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2009). "Šāpur II". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240. ISBN 978-0857716668.

- Daryaee, Touraj; Rezakhani, Khodadad (2016). From Oxus to Euphrates: The World of Late Antique Iran. H&S Media. pp. 1–126. ISBN 9781780835778.

- Daryaee, Touraj; Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "The Sasanian Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 1–236. ISBN 9780692864401.

- Daryaee, Touraj; Canepa, Matthew (2018). "Mazdak". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- Daryaee, Touraj; Nicholson, Oliver (2018). "Qobad I (MP Kawād)". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- Daryaee, Touraj. "Yazdegerd II". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Frye, R. N. (1983). "The political history of Iran under the Sasanians". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3(1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. pp. 1–411. ISBN 9783406093975.

false.

- Gadjiev, Murtazali (2017a). "Apzut Kawāt wall". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Gadjiev, Murtazali (2017b). "Construction Activities of Kavād I in Caucasian Albania". Iran and the Caucasus. Brill. 21 (2): 121–131. doi:10.1163/1573384X-20170202.

- Gaube, H. (1986). "Arrajān". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5. pp. 519–520.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). "Justinian's First Persian War and the Eternal Peace". The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. 82–97. ISBN 0-415-14687-9.

- Howard-Johnston, James (2013). "Military Infrastructure in the Roman Provinces North and South of the Armenian Taurus in Late Antiquity". In Sarantis, Alexander; Christie, Neil (eds.). War and Warfare in Late Antiquity: Current Perspectives. Brill. ISBN 978-9004252578.

- Kettenhofen, Erich (1994). "Darband". Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. VII. pp. 13–19.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693912.

- Martindale, John R., ed. (1980). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume II, AD 395–527. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20159-4.

- Martindale, John R., ed. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume III, AD 527–641. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20160-8.

- McDonough, Scott (2011). "The Legs of the Throne: Kings, Elites, and Subjects in Sasanian Iran". In Arnason, Johann P.; Raaflaub, Kurt A. (eds.). The Roman Empire in Context: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 290–321. doi:10.1002/9781444390186.ch13. ISBN 9781444390186.

- McDonough, Scott (2013). "Military and Society in Sasanian Iran". In Campbell, Brian; Tritle, Lawrence A. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Warfare in the Classical World. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–783. ISBN 9780195304657.

- Langarudi, Rezazadeh (2002). "Fahraj". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Modarres, Ali. "Meybod". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Miri, Negin (2012). "Sasanian Pars: Historical Geography and Administrative Organization". Sasanika: 1–183.

- Payne, Richard E. (2015a). A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity. Univ of California Press. pp. 1–320. ISBN 9780520961531.

- Payne, Richard (2015b). "The Reinvention of Iran: The Sasanian Empire and the Huns". In Maas, Michael (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila. Cambridge University Press. pp. 282–299. ISBN 978-1-107-63388-9.

- Potts, Daniel T. (2018). "Sasanian Iran and its northeastern frontier". In Mass, Michael; Di Cosmo, Nicola (eds.). Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–538. ISBN 9781316146040.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2017). "Kārin". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1991). "Chinese-Iranian relations i. In Pre-Islamic Times". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. V, Fasc. 4. pp. 424–431.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 9781474400305.

- Sauer, Eberhard (2017). Sasanian Persia: Between Rome and the Steppes of Eurasia. London and New York: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–336. ISBN 9781474401029.

- Schindel, Nikolaus (2013a). "Kawād I i. Reign". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XVI, Fasc. 2. pp. 136–141.

- Schindel, Nikolaus (2013b). "Kawād I ii. Coinage". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XVI, Fasc. 2. pp. 141–143.

- Schindel, Nikolaus (2013c). "Sasanian Coinage". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199733309.

- Schippmann, Klaus (1999). "Fīrūz". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IX, Fasc. 6. pp. 631–632.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2005). "Sasanian dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition.

- Sundermann, W. (1986). "Artēštārān sālār". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6. p. 662.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century. Volume 1, Part 1: Political and Military History. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 978-0-88402-214-5.

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2017). "Sasanian political ideology". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–1021. ISBN 9780190668662.

- Spuler, Bertold (2014). Iran in the Early Islamic Period: Politics, Culture, Administration and Public Life between the Arab and the Seljuk Conquests, 633-1055. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-28209-4.

- Tafazzoli, Ahmad (1989). "Bozorgān". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 4. Ahmad Tafazzoli. p. 427.

- Toumanoff, Cyril (1969). "Chronology of the early kings of Iberia". Traditio. Cambridge University Press. 25: 1–33. doi:10.1017/S0362152900010898. JSTOR 27830864. S2CID 151472930. (registration required)

- Võõbus, Arthur (1965). History of the School of Nisibis. Secrétariat du Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium.

Further reading

- Crone, Patricia (2012). The Nativist Prophets of Early Islamic Iran: Rural Revolt and Local Zoroastrianism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107642386.

- Gil, Moshe (2012). "King Qubādh and Mazdak". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. University of Chicago Press. 71 (1): 75–90. doi:10.1086/664453. S2CID 163367979.

_of_Firdawsi_LACMA_M.73.5.23.jpg.webp)