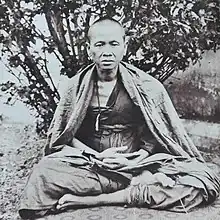

Khruba Siwichai

Khruba Siwichai (Thai: ครูบาศรีวิชัย, also spelled Sriwichai) was a Thai Buddhist monk born in 1878 in the village of Ban Pang, Li District, in Lamphun Province of northern Thailand.[1] Siwichai is best known for the building of many temples during his time, his charismatic and personalistic character, and his political conflict with local authorities.

Khruba Siwichai | |

|---|---|

ครูบาศรีวิชัย | |

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | Fuen or Fahong 11 June 1878 |

| Died | 21 February 1939 (aged 60) |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Nationality | Thai |

| School | Theravada |

| Dharma names | Sirivijaya |

| Temple | Wat Ban Pang |

Early life and rise to monkhood

Siwichai was born to a humble peasant family in Ban Pang. Early accounts suggest that on the particular day that he was born there was a heavy thunderstorm and rain and was thus given the name of In Fuen, "quake" or Fahong, "thunder". Given the context of his birth, many around his village accredited him as the phu mee boon or a person having merit.[2] As a child, Fahong has been described to have compassion with all beings. Previous biographies cite that as a child he would release the animals that his father caught for cooking or beg him to not hit fish as their heads would hurt.[3]

From an early age, Fehong expressed a serious interest in Buddhism as he believed that his family's present state of poverty was a consequence of his misbehavior in his previous life and became a well behaved monk so his parents would have a better life. He was ordained as a novice (samanera) at the age of 18 at the local temple in the village of Ban Pang. Fahong was ordained as a monk in 1899 at Wat Ban Hong Luang at which point the took a religious name of Phra Siwichai [4] and went on to study with his first teacher, Khruba Khattiya in Wat Bang Pan.

As a student, the Khruba was known to have great respect and reverence towards the science of magic and spells. Additionally, Khruba Siwichai gained reputation for his asceticism. Traditional accounts of his early career suggest Khruba Siwichai was an exemplary Buddhist monk, eating only one vegetarian meal a day and refraining from "habit-forming practices as chewing betel and fermented tea leaves, and smoking".[5] His generosity and compassion were evident to everyone around him. One of his biographers Sanga Suphapha said the following:

- He showed compassion and mercy towards anyone who appealed to him ... he did nothing that was useful to himself. He was not a monk of rank, but only a monk of the people ... As a result he was always moving about, doing useful things wherever he went ... They were things that led Buddhists to rejoice that a monk with the wide heart of a Bodhisattva had been born into the world.[6]

Temple constructions

Khruba Siwichai became the new abbot of Wat Ban Pang after the former abbot, Khruba Khattiya, passed away.[7] Soon after, he began building a new temple and finished it in 1904, naming it Wat Sri Don Chai Sai Mun Bun Rueng even though villagers still referred to it as a Wat Ban Pang.[8] This new temple was but the beginning of a career involving the repair and construction of more than one hundred religious and non-religious projects such as temples, roads, and bridges. Some of his more renowned monuments were temples on the top of Doi Suthep, the Suan Dok temple in Chiang Mai and the reliquary at the Camthewi temple in Lamphun.[9] Villagers were urged to donate their money and labor as an act of merit (bun). Nationally known Buddhist monk and writer Phikkhu Panyanantha described Khruba Siwichai as a monk not of rank, but of the people and gained massive popular support and the status of a ton bun (holy men).[10] A highly respected northern Thai monk writes:

Khruba Siwichai had done many good deeds to Buddhism. His goodness could hardly fade away from northern people' minds and especially for his many construction and renovation works. It seems that there were no other monks in this region who had done such thing like Khruba Siwichai.[11]

The Khruba's charismatic, and often rebellious, personality increased his reputation and influence. Many began to ascribe the title of bodhisatta with miraculous powers.[12] Early biographies report that the renovated Wat Phra Singha temple was constructed with the help of angels as the workers who were constructing the temple found pots full of gold.[13] Other accounts suggest that when working in any weather conditions they did not get hot or wet. Khruba consistently denied having these special powers, but his public ascription as a bodhisatta remained.

Conflict with local and national authorities

Khruba Siwichai came into serious conflict with the sangha, the authorities of the national order of monks, and the Siamese state. The Sangha Act of 1902 stipulated that monk ordinations by any senior monk required the permission of his respective sangha superior and of the District Officer. Khruba Siwichai had ordained monks and novices without been officially recognized as a "preceptor of the Thai hierarchy" leading to his confinement in a temple in Lamphun in about 1915-1916.[14] Siwichai's perceived ignorance and disregard for the law led to his years of imprisonment.

While most of the scholarship centers on that charge as the source of Siwichai's conflict, available evidence may complicate this issue. Firstly, Siwichai may have been fully aware and willing to comply with the law. Apparently, two officials within the central Thai administration, the kromakarn which represented the Religious Affairs Department and the naaj amphur who worked on behalf of the Ministry of Interior, denied Siwichai's request to appoint the monks. A detailed account in the Bangkok Times Weekly Mail describes the situation:

- About five years ago the [Siwichai] proposed to ordain a new priest, and the sent the Kamnan [subdistrict head] and head-man of the village to ask for a license from the Kromakarn and Nai Amphur. They were told that the license would be issued later, and that meantime they could be preparing for the ceremony. The priest did make the preparations - a Buat Nak [ordination ceremony] costs some money - and when it was near lent, the again sent the Kamnan and Phu Yai Ban [village headman] to get the promised license. This time it was definitely refused. Taking the view that there was nothing wrong in ordaining an honest man, the priest carried out the rite without a license.[15]

Siwichai was indeed the Abbot of his village temple at the time and the head of the temple in his subdistrict. Having held the title of priesthood for more than ten years, it is likely that he would have been in good standing to conduct and approve his own ordinations. It is much more plausible that the secular officials may have denied approval of the monks that were to be ordained due to certain clauses in the 1913 Ordination act. The act lists punishments for monks who ordained "forbidden" men which may have ranged from people pending court cases, evading taxes, or people simply fleeing taxes or military service.[16]

Furious over Siwichai's insubordination, he was arrested by the police and brought to the Wat Lii Luang temple where the district prelate Phrakhru Maharatnkhon resided. However, he was quickly sent to the temple of Lapmhun out of fear of the growing following that had gathered over the last four days in front of Wat Lii Luang. He was released soon after in Lamphun. Siwichai was arrested again a year after his initial imprisonment. The district prelate ordered all monks and novices under his jurisdiction to meet in order to certify that the religious leaders were acting in accord with all regulations. Once Siwichai decided not to go, the rest of the monks decided to not go as well.[17] Consequently, Siwichai was arrested once again and brought to the prelate in Lamphun. A committee was appointed by the provincial prelate and decided to forbid Siwichai to perform his duties as an ordainer and was demoted from his role as an abbot and subdistrict head. Siwichai was thus imprisoned for one year at Wat Phrathat Haripunchai in the city of Lamphun and returned to his temple in Baang Pang. This time, however, without the title of abbot and subdistrict head.

Siwichai was consequently banned from Lamphun in January 1918.[18] However, he refused to leave and in 1920 was invited by the lord (chao) of Lamphun to receive the alms of the city. On his Journey to Lamphun, then was followed by nearly 600 men and women, leading the officials to think that the "priest had come to create a revolt" and was, once again, arrested in Waluang.[19] This was brought to the attention of the Supreme Patriarch (sangharaja) in Bangkok who formed a committee in order to investigate the eight charges brought against Siwichai. The committee concluded ruled that the punishment of imprisonment for the ordination of monks should have come from Bangkok and that Siwichai's failure to attend the meetings were too severe.[20] The supreme patriarch sent him home and even contributed funds to help the costs of his journey back.[21] In this sense, it is apparent that the Bangkok sangha recognized many of Siwichai's actions and his refusal to cooperate with many of the local secular officials.

Death and influence

The Khruba died near the age of 61 in his home village at Wat Ban Pang on 21 February 1939.[22] He died out of exhaustion and sickness which were largely influenced by a long battle with hemorrhoids.[23] His body was cremated in 1946. Early accounts record that in the day of his cremation the sky became suddenly dark with heavy unexpected rain although it was not rainy season.[24]

Today, the Wat Ban Pang temple serves as a museum for the late Khruba, built by one of his original biographers Phra Anan Phutthathammo in June 1989.[25] The museum's entrance is protected by two statues of a Tiger from Khruba Siwichai's birth year. By the staircase, a small shrine has been placed for monks and others to worship Khruba Siwichai and recite his prayers. The museum features collections of paraphernalia associated with his various construction projects including maps, a bench for resting, and a carrier bicycle.[26] Additionally, the most notable temples that the Khruba built contain shrines built in his honor. For instance, the temple of Wat Phra Singha contains a shrine of Khruba Siwichai and features a long bronze statue of him, standing, in front of the "vihara". Similar bronze statues can be seen in the Wat Suan Dok temple and at the hilltop of Doi Suthep.[27]

References

Footnotes

- Cohen 2001, 228

- Treesahakiat 2011, 34-35

- Treesahakiat 2011, 35

- Treesahakiat 2011, 37

- Swearer 2005, 79

- Cohen 2001, 228

- Treesahakiat 2011, 37

- Treesahakiat 2011, 38

- Cohen 2001, 228

- Treesahakiat 2011, 47

- Treesahakiat 2011, 41

- Swearer 2005, 72

- Treesahakiat 2011, 44

- Keyes 1971, 557

- Bowie 2014, 715

- Bowie 2014, 716

- Premchit 2000, 33

- Premchit 2000, 37

- Bowie 2014, 716

- Bowie 2014, 717

- Bowie 2014, 717

- "ไขปริศนาวันเวลาที่ครูบาเจ้าศรีวิชัยมรณภาพ 20 กุมภาพันธ์, 21 กุมภาพันธ์ หรือ 22 มีนาคม?". มติชนสุดสัปดาห์. 31 August 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- Treesahakiat 2011, 50

- Treesahakiat 2011, 50

- TreesahakiatIsara 2011, 115

- TreesahakiatIsara 2011, 115

- TreesahakiatIsara 2011, 110

Bibliography

- Bowie, Katherine. "The Saint with Indra's Sword: Khruubaa Srivichai and Buddhist Millenarianism in Northern Thailand." Comp Stud Soc Hist Comparative Studies in Society and History 56.03 (2014): 681-713

- Cohen, Paul T. "Buddhism Unshackled: The Yuan 'Holy Man' Tradition and the Nation- State in the Tai World." Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 32, no. 2 (June 2001): 227-247.

- Keyes, Charles F. "Death of Two Buddhist Saints in Thailand." In Charisma and Sacred Biography, edited by Michael A. Williams, 149-180. Chambersburg, PA: American Academy of Religion, 1982.

- Premchit, Sommai. Prawati Khruba Siwichai nak bun haeng Lanna [The biography of Khruba Siwichai, the holy man of Lanna]. Chiang Mai: Ming Muang Press, 2000.

- Swearer, Donald K., Sommai Premchit, and Phaithoon Dokbuakaew. Sacred Mountains Of Northern Thailand And Their Legends. University of Washington Press, 2005.

- Treesahakiat, I. The Significance of Khruba Sriwichai's Role in Northern Thai Buddhism: His Sacred Biography, Meditation Practice and Influence (Thesis, Master of Arts). University of Otago. 2011.