Kielce pogrom

The Kielce pogrom was an outbreak of violence toward the Jewish community centre's gathering of refugees in the city of Kielce, Poland, on 4 July 1946 by Polish soldiers, police officers, and civilians[1] during which 42 Jews were killed and more than 40 were wounded.[1][2] Polish courts later sentenced nine of the attackers to death in connection with the crimes.[1]

| Kielce pogrom | |

|---|---|

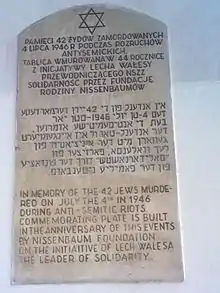

Plaque on ulica Planty 7, Kielce, dedicated by Lech Wałęsa, 1990 | |

| Location | Kielce, Poland |

| Date | 4 July 1946 Morning until evening (official cessation at 3 p.m.) |

| Target | Polish Jews |

| Deaths | 38 to 42 |

As the deadliest pogrom against Polish Jews after the Second World War, the incident was a significant point in the post-war history of Jews in Poland. It took place only a year after the end of the Second World War and the Holocaust, shocking Jews in Poland, non-Jewish Poles, and the international community. It has been recognized as a symptom of the precarious condition of Eastern European Jewish communities in the aftermath of the Holocaust and as a catalyst for the flight from Poland of most remaining Polish Jews who had survived the war.[3][4]

Background

Relations between Jewish and non-Jewish Poles were already strained before the war, as antisemitic propaganda was spread by members of parliament and clergy. According to Alina Skibińska and Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, during the 1930s "the relations between the communities ... began to increasingly resemble apartheid."[5]

During the German occupation of Poland, Kielce[6] and the villages around it[7] were completely ethnically cleansed by the Nazis[7][8] of its pre-war Jewish community, most of which perished in The Holocaust. By the summer of 1946, some 200 Jews, many of them former residents of Kielce, had returned from the Nazi concentration camps or refuge in the Soviet Union. About 150–160 of them were quartered in a single building administered by the Jewish Committee of Kielce Voivodeship at Planty,[9] a small street in the centre of the town.

On 1 July 1946, an eight-year-old non-Jewish Polish boy, Henryk Błaszczyk, was reported missing by his father Walenty Błaszczyk. According to the father, upon his return two days later the boy claimed he had been kidnapped by an unknown man, allegedly a Jew or a gypsy. Two days later, the boy, his father and the neighbour went to a local Citizens' Militia (state police) station. While passing the "Jewish house" at 7 Planty Street, Henryk pointed at a man nearby who, he said, had allegedly imprisoned him in the house's cellar. At the police station, Henryk repeated his story that he had been kidnapped and specified the Jews and their house as involved in his disappearance. A Civic Militia patrol of more than a dozen men was then dispatched on foot by the station commander Edmund Zagórski to search the house at 7 Planty Street for the place where Henryk had allegedly been kept.[10]

Although the kidnapping claim was quickly withdrawn,[11] Henryk Błaszczyk remained publicly silent about the events until 1998, when, in an interview to a Polish journalist he admitted he was never kidnapped but was living with an "unknown family" in a nearby village and was treated well. He perceived his disappearance as happening with his father's awareness and concerted by the communist security service. After returning home he was categorically commanded by his father not to discuss anything that happened and reaffirm only the story of "Jewish abduction" if ever asked. He was threatened to keep quiet long after 1946, which he did out of fear until the end of communist rule in Poland.[12]

Civic Militia publicised the rumours of the kidnapping and further announced that they were planning to search for the bodies of non-Jewish Polish children supposedly ritually murdered and kept in the house, resulting in the gathering of civilian spectators.[10] A confrontation ensued between the militia forces and officers of the Ministry of Public Security of Poland (UBP), which had been called in on the suspicion that the incident was a Jewish "provocation" to stir up unrest.

During the morning, the case came to the attention of other local state and military organs, including the Polish People's Army (LWP – communist controlled regular army), the Internal Security Corps (KBW, interior ministry paramilitary), and the Main Directorate of Information of the Polish Army (GZI WP, military intelligence and counterintelligence). About 100 soldiers and five officers were dispatched to the location at about 10 am. The soldiers were unfamiliar with the circumstances, but soon picked up rumors from the people in the street, who at this time commenced pelting the building with stones.[10]

Outbreak of violence

The Civic Militia and soldiers then forcibly broke into the building only to discover that it did not contain any abducted children as claimed. The inhabitants of the house, who had proper permits to bear arms for self defence, were ordered to surrender their weaponry and give up valuables. Someone (unclear who) started firing a weapon. Civic Militia and the KBW opened fire, killing and wounding a number of people in the building. In response, shots were fired from the Jewish side killing two or three non-Jewish Poles, including a Civic Militia officer. The head of the local Jewish Committee, Dr Seweryn Kahane, was fatally wounded by a GZI WP officer while telephoning the Kielce office of Public Security for help. A number of local priests attempted to enter the building but were stopped by militia officers, who vowed to control the situation.[10]

Following the initial murders inside the building, numerous Jews were driven outdoor by soldiers and later attacked with stones and clubs by civilians who crowded surrounding streets. By noon, the arrival of a large group of estimated about 600 to 1,000 workers from Ludwików steel mill, led by activists of Poland's ruling Polish Workers' Party (PPR, communist party), opened the next stage of the pogrom. Approximately 20 Jews were battered to death by the workers armed with iron rods and clubs. Some of the workers were members of the ORMO (volunteer reserve militia) and at least one possessed a handgun. Neither the military or security heads, including a Soviet army advisor, nor the local civic leaders, sought to prevent the aggression. A unit of Civic Militia cadets which also arrived at the scene did not intervene, but some of its members joined in the looting and violence which continued inside and outside the building.[13]

Among the slain Jews, nine had been shot dead, two were killed with bayonets, and the rest beaten or stoned to death. The dead included women and children. The mob also killed a Jewish nurse (Estera Proszowska), whom the attackers had mistaken for a Polish female attempting to aid the Jews. Two Jewish people not residing at Planty Street dwelling were also murdered on this day in separate incidents. Regina Fisz, her three-week old child, and a male companion were abducted at their home at 15 Leonarda Street by a group of four men led by Civic Militia corporal Stefan Mazur. They were robbed and driven out of the city, where Regina and her baby were shot while allegedly trying to escape, while her friend did manage to escape. Three non-Jewish Poles were among the dead. Two uniformed state servicemen were killed in gunfire exchange, most likely shot by Jews defending themselves. The cause of death of the third man remains unexplained.[13]

Cessation of violence

The pogrom ended at roughly 3:00 p.m. with the arrival of new security units from a nearby Public Security Academy, advanced by Colonel Stanisław Kupsza, and additional troops from Warsaw.[10] After warning shots discharge, on the order of Major Kazimierz Konieczny, the new troops swiftly restored order, posted guards, and removed all the survivors as well as corpses from the dwelling and its proximity.

The violence, nevertheless, did not stop. Wounded Jews being taken to the local hospital were beaten and robbed by soldiers,[10] and the injured were assaulted in the hospital by other patients. A civilian crowd approached one of the hospitals and demanded that the hurt Jews be handed over, but the hospital staff refused.

Trains passing through Kielce's main railway station were scrutinized for Jews by civilians and SOK railway guards, resulting in at least two passengers being murdered. As many as 30 more may have been killed in this manner, as the train murders reportedly continued for several months after the pogrom.[13] The large-scale disorder in Kielce ultimately ended some nine hours after it started. Polish born Julia Pirotte, a well-known French photojournalist with the French Resistance, photographed the pogrom's immediate aftermath.[14]

Aftermath

Reaction of the Communist government

One immediate reaction of the Communist government of Poland was to attempt to blame the pogrom on Polish independence underground,[15] alleging that uniformed members of anti-communist formations backing the Polish government-in-exile were egging the mob on. At the funeral of the Jewish victims, the Minister of Public Security, Stanisław Radkiewicz, stated that the pogrom was "a deed committed by the emissaries of the Polish government in the West and General Anders, with the approval of Home Army soldiers." Other early official statements at the time followed this line.[16]

After these initial attempts to blame the pogrom on "reactionary elements" opposed to the Communist regime, the Communist Party changed its policy. Party memoranda and internal reports pointed out that the local population felt no sympathy for the victims and was unwilling to publicly condemn the perpetrators.[17] The July 1946 report of the Radom Department of Information and Propaganda noted that "the Jewish pogrom in Kielce met with the moral approval of many groups in our society".[17] According to Gross, the Communist Party decided not to publicly condemn the pogrom because at the time it was "deeply committed to the struggle for the hearts and minds of the Polish population".[17] In July 1946, the Secretariat of the Central Committee did not place on the agenda the issue of the pogrom, and documents submitted by high party officials and other internal reports described the pogrom as an explosion of popular anger against the "parasitic elements" of society".[17] Gross concludes that in post-war Poland, "while Jews were literally running away from Communism" and leaving for Israel, "the Communists were politically running away from the Jews", in an effort to expand their consensus base in Polish society.[18]

Additional investigation into the circumstances of the massacre was opposed by the communist regime until the era of Solidarity, when in December 1981 an article was published in the Solidarity newspaper Tygodnik Solidarność.[19] However, the return of repressive government meant that files could not be accessed for research until after the fall of Communism in 1989, by which time many eyewitnesses had died. It was then discovered that many of the documents relating to the pogrom had been allegedly destroyed by fire or deliberately by military authorities.[20]

Trials

Between 9 and 11 July 1946, twelve civilians (one of them apparently mentally challenged) were arrested by MBP officers as perpetrators of the pogrom. The accused were tried by the Supreme Military Court in a joint show trial. Nine were sentenced to death and executed the following day by firing squad on the orders of Polish Communist leader Bolesław Bierut. The remaining three received prison terms ranging from seven years to life. According to author Krzysztof Kąkolewski (Umarły cmentarz), the twelve had been picked up from the watching crowd by the secret police.[2]

Aside from Kielce Voivodeship's Civic Militia commandant, Major Wiktor Kuźnicki, who was sentenced to one year for "failing to stop the crowd" (he died in 1947), only one militia officer was punished — for the theft of shoes from a dead body. Mazur's explanation regarding his killing of the Fisz family was accepted. Meanwhile, the regional UBP chief, Colonel Władysław Sobczyński, and his men were cleared of any wrongdoing. The official reaction to the pogrom was described by Anita J. Prazmowska in Cold War History, Vol. 2, No. 2:

Nine participants in the pogrom were sentenced to death; three others were given lengthy prison sentences. Militiaman, military men and functionaries of the UBP were tried separately and then unexpectedly all, with the exception of Wiktor Kuznicki, Commander of the MO, who was sentenced to one year in prison, were found not guilty of "having taken no action to stop the crowd from committing crimes." Clearly, during the period when the first investigations were launched and the trial, a most likely politically motivated decision had been made not to proceed with disciplinary action. This was in spite of very disturbing evidence that emerged during the pre-trial interviews. It is entirely feasible that instructions not to punish the MO and UBP commanders had been given because of the politically sensitive nature of the evidence. Evidence heard by the military prosecutor revealed major organisational and ideological weaknesses within these two security services.[21]

The neighbour of the Błaszczyk family who had originally suggested to Henryk that he had been kidnapped by Jews was subsequently tried, but acquitted.[10]

Effects on Jewish emigration from Poland

The ruthlessness of the murders put an end to the expectation of many Jews that they would be able to resettle in Poland after the end of the Nazi German occupation and precipitated a mass exodus of Polish Jewry.[22] Bożena Spank, a historian at Wrocław University estimated that from July 1945 until June 1946 about fifty thousand Jews crossed the Polish border illegally. In July 1946, almost twenty thousand decided to start a new life abroad.[10] Polish Minister Marian Spychalski, motivated by political and humanitarian reasons, signed a decree allowing Jews to leave officially without visas or exit permits, and the Jewish emigration from Poland increased dramatically.[23] In August 1946 the number of emigrants increased to thirty thousand. In September 1946, twelve thousand Jews left Poland.[10] By the spring of 1947, wrote Bernhard and Szlajfer, the number of Jews in Poland – in large part arriving from the Soviet Union – declined from 240,000 to 90,000 due to mass migration.[24] Britain demanded that Poland halt the Jewish exodus, but their pressure was largely unsuccessful.[25]

Reaction of the Catholic Church

Six months before the Kielce pogrom, during the celebration of Hanukkah, a hand grenade had been thrown into the headquarters of the local Jewish community. The Jewish Community Council had approached the Bishop of Kielce, Czesław Kaczmarek, requesting that he admonish the Polish people to refrain from attacking the Jews. The bishop refused, replying that "as long as the Jews concentrated upon their private business Poland was interested in them, but at the point when Jews began to interfere in Polish politics and public life, they insulted the Poles' national sensibilities".[26]

Similar remarks were delivered by the Bishop of Lublin, Stefan Wyszyński, when he was approached by a Jewish delegation. Wyszyński stated that the widespread hostility to Jews was provoked by Jewish backing of Communism (there was a widespread perception that Jews were supportive of Soviet-installed Communist administration in Poland; see Żydokomuna), which had also been the reason why "the Germans murdered the Jewish nation". Wyszyński also gave some credence to blood libel stories, commenting that the issue of the use of Christian blood was never fully clarified.[27]

The controversial stance of the Polish Roman Catholic Church towards anti-Jewish violence was criticised by the American, British and Italian ambassadors to Poland. Reports of the Kielce pogrom caused a major sensation in the United States, leading the American ambassador to Poland to insist that Cardinal August Hlond hold a press conference and explain the position of the church. In the conference held on 11 July 1946, Hlond condemned the violence, but attributed it not to racial causes but to rumours concerning the killing of Polish children by Jews. Hlond put the blame for the deterioration in Polish-Jewish relations on collaboration with the Soviet-backed Communist occupiers, Jews "occupying leading positions in Poland in state life". This position was echoed by Polish rural clergy and Cardinal Sapieha, who reportedly stated that the Jews had brought it upon themselves.[28]

Other reactions

Historian Łukasz Krzyżanowski analyzed the reactions to the pogrom and concludes: "Simply put, the Kielce pogrom met with approbation in many circles." He documents that some meetings held to commemorate the victims were interrupted by antisemitic shouting and groups of workers could not reach agreement to pass resolutions condemning the pogrom.[29]

Commemoration

Following the fall of communism, several commemorative plaques were unveiled in Kielce. In 1990 the first plaque was unveiled following the involvement of then Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa.[30][31] A monument by New York City-based artist Jack Sal entitled White/Wash II commemorating the victims was dedicated on 4 July 2006, in Kielce, on the 60th anniversary of the pogrom. At the dedication ceremony, a statement from the President of the Republic of Poland Lech Kaczyński condemned the events as a "crime and a great shame for the Poles and tragedy for the Polish Jews". The presidential statement asserted that in today's democratic Poland there is "no room for antisemitism" and brushed off any generalizations of the antisemitic image of the Polish nation as a stereotype.[32][33][34] Another monument intended to be a representative grave for the victims, was unveiled in the city in 2010.[35]

See also

- Anti-Jewish violence in Poland, 1944–1946

- Białystok pogrom

- Jedwabne pogrom

- Kielce pogrom (1918)

- Kraków pogrom

- Szczuczyn pogrom

- Tykocin pogrom

- Wąsosz pogrom

- From Hell to Hell, a 1997 Belarusian drama film about the Kielce pogrom

References

- THE KIELCE POGROM: A BLOOD LIBEL MASSACRE OF HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Interview with Krzysztof Kąkolewski, Archive copy at the Wayback Machine Also available with purchase at "To Moskwa zaplanowała ten mord" (The murder was planned in Moscow), Tygodnik Angora – "Przegląd prasy krajowej i światowej", Łódź, 29/2006 (839); section Kultura, p. 56. Copy available at Forum historycy.org, 3 July 2006, and at Gazeta.pl Forum (incomplete) Archived 7 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 7 June 2016. (in Polish)

- Engel, David (1998). "Patterns of Anti-Jewish Violence In Poland, 1944-1946" (PDF). Yad Vashem Studies Vol. XXVI. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. pp. 7, 28. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- "The Kielce Pogrom: A Blood Libel Massacre of Holocaust Survivors". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- Tokarska-Bakir, Joanna; Skibińska, Alina (2013). ""Barabasz" and the Jews: From the history of the "Wybraniecki" Home Army Partisan Detachment". Holocaust Studies and Materials (3): 13–78. ISSN 1689-9644. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Kielce- Yad Vashem

- Connelly, John (14 November 2012). "The Noble and the Base: Poland and the Holocaust". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Marta Kubiszyn; Zofia Sochańska; Ariana G. Lee (2009–2015). "Kielce". Virtual Shtetl. Translated by Aleksandra Bilewicz. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016.

- Williams, Anna, The Kielce Pogrom Archived 4 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, ucsb.edu; accessed 5 July 2016.

- Bożena Szaynok. "The Jewish Pogrom in Kielce, July 1946 – New Evidence". Intermarium. 1 (3). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

-

Lawrence, W.H. (6 July 1946). "Poles Declare Two Hoaxes Caused High Toll in Pogrom". The New York Times. Page 1.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Stempniak, Anna (2016). "Porwanie, którego nigdy nie było. Prawda o pogromie kieleckim". polskieradio.pl. Polskie Radio. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- (in Polish) Pogrom na Plantach Archived 3 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Rzeczpospolita, 1 July 2006.

- "Julia Pirotte's photographs from the aftermath of the massacre are available online at Yad Vashem". Yad Vashem.

- "Pogrom Żydów w Kielcach | Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN w Warszawie". polin.pl. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- Kamiński & Żaryn 2006, p. 29-33.

- Gross 2006, chpt. 4, "The Kielce Pogrom: Reactions".

- Gross 2006, chpt. 7. Conclusions.

- Kamiński & Żaryn 2006, p. 123.

- Kamiński & Żaryn 2006, pp. 123–124.

- Anita Prażmowska (2002). "Case Study: The Pogrom in Kielce". Poland's Century: War, Communism and Anti-Semitism. London, UK: London School of Economics and Political Science. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009.

- Abraham Duker. Twentieth century blood libels in the United States. In: Alan Dundes. The Blood Libel Legend: A Casebook in Anti-Semitic Folklore. University of Wisconsin Press, 1991.

- Marrus, Michael Robert; Aristide R. Zolberg (2002). The Unwanted: European Refugees from the First World War Through the Cold War. Temple University Press. p. 336. ISBN 1-56639-955-6. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018.

This gigantic effort, known by the Hebrew code word Brichah(flight), accelerated powerfully after the Kielce pogrom in July 1946

- Michael Bernhard, Henryk Szlajfer, From the Polish Underground, page 375 Archived 14 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine Published by Penn State Press, 2004, ISBN 0-271-02565-4, ISBN 978-0-271-02565-0. 500 pages

- Kochavi, Arieh J. (2001). Post-Holocaust Politics: Britain, the United States & Jewish Refugees, 1945–1948. The University of North Carolina Press. p. xi. ISBN 0-8078-2620-0.

Britain exerted pressure on the governments of Poland.

- Aleksiun, Natalia (2010). "The Polish Catholic Church and the Jewish Question in Poland, 1944–1948" (PDF). Yad Vashem. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2005. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- Eli Lederhendler (2005). Jews, Catholics, and the Burden of History. Oxford University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-19-530491-8.

- Peter C. Kent (2002). The Lonely Cold War of Pope Pius XII: The Roman Catholic Church and the Division of Europe. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 128.

- Krzyżanowski, Łukasz (2020). Ghost Citizens: Jewish Return to a Postwar City. Harvard University Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0-674-98466-0.

- "Tablice upamiętniające pogrom kielecki / Obiekty / Pomniki i tablice pamiątkowe w Kielcach / Oficjalna strona Miasta Kielce". www.um.kielce.pl. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "Anti-Jewish Violence in Poland After Liberation | www.yadvashem.org". anti-jewish-violence-in-poland-after-liberation.html. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Matthew Day, 60 years on, Europe's last pogrom still casts dark shadow, The Scotsman, 5 July 2006.

- "60. rocznica Pogromu w Kielcach – pomnik / Obiekty / Pomniki i tablice pamiątkowe w Kielcach / Oficjalna strona Miasta Kielce". www.um.kielce.pl. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "Pogrom kielecki – to była zbrodnia i hańba". WPROST.pl (in Polish). 17 July 2006. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "05.07.2010 – odsłonięcie odnowionego grobowca ofiar pogromu kieleckiego | Wirtualny Sztetl". sztetl.org.pl. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

Sources

- Gross, Jan Tomasz (2006). Fear. Anti-semitism in Poland after Auschwitz. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-43096-0. OCLC 320326507.

- Kamiński, Łukasz; Żaryn, Jan (2006). Reflections on the Kielce Pogrom. Institute of National Remembrance. ISBN 83-60464-23-5.