Æthelstan

Æthelstan or Athelstan (/ˈæθəlstæn/; Old English: Æðelstān [ˈæðelstɑːn]; Old Norse: Aðalsteinn; lit. 'noble stone';[4] c. 894 – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939.[lower-alpha 1] He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his first wife, Ecgwynn. Modern historians regard him as the first King of England and one of the "greatest Anglo-Saxon kings".[6] He never married and had no children; he was succeeded by his half-brother, Edmund I.

| Æthelstan | |

|---|---|

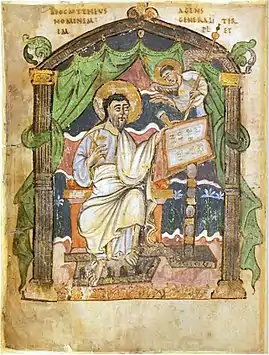

.jpg.webp) Æthelstan presenting a book to St Cuthbert, an illustration in a manuscript of Bede's Life of Saint Cuthbert, probably presented to the saint's shrine in Chester-le-Street by Æthelstan when he visited the shrine on his journey to Scotland in 934.[1] He wore a crown of a similar design on his crowned bust coins.[2] It is the oldest surviving portrait of an English king and the manuscript is the oldest surviving made for an English king.[3] | |

| King of the Anglo-Saxons | |

| Reign | 924–927 |

| Coronation | 4 September 925 Kingston upon Thames |

| Predecessor | Edward the Elder |

| King of the English | |

| Reign | 927 – 27 October 939 |

| Predecessor | Title established |

| Successor | Edmund I |

| Born | c. 894 Wessex |

| Died | 27 October 939 (aged about 45) Gloucester, England |

| Burial | |

| House | Wessex |

| Father | Edward the Elder |

| Mother | Ecgwynn |

When Edward died in July 924, Æthelstan was accepted by the Mercians as king. His half-brother Ælfweard may have been recognised as king in Wessex, but died within three weeks of their father's death. Æthelstan encountered resistance in Wessex for several months, and was not crowned until September 925. In 927, he conquered the last remaining Viking kingdom, York, making him the first Anglo-Saxon ruler of the whole of England. In 934, he invaded Scotland and forced Constantine II to submit to him. Æthelstan's rule was resented by the Scots and Vikings, and in 937 they invaded England. Æthelstan defeated them at the Battle of Brunanburh, a victory that gave him great prestige both in the British Isles and on the Continent. After his death in 939, the Vikings seized back control of York, and it was not finally reconquered until 954.

Æthelstan centralised government; he increased control over the production of charters and summoned leading figures from distant areas to his councils. These meetings were also attended by rulers from outside his territory, especially Welsh kings, who thus acknowledged his overlordship. More legal texts survive from his reign than from any other 10th-century English king. They show his concern about widespread robberies and the threat they posed to social order. His legal reforms built on those of his grandfather, Alfred the Great. Æthelstan was one of the most pious West Saxon kings, and was known for collecting relics and founding churches. His household was the centre of English learning during his reign, and it laid the foundation for the Benedictine monastic reform later in the century. No other West Saxon king played as important a role in European politics as Æthelstan, and he arranged the marriages of several of his sisters to continental rulers.

Background

By the ninth century the many kingdoms of the early Anglo-Saxon period had been consolidated into four: Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria and East Anglia.[7] In the eighth century, Mercia had been the most powerful kingdom in southern England, but in the early ninth, Wessex became dominant under Æthelstan's great-great-grandfather, Egbert. In the middle of the century, England came under increasing attack from Viking raids, culminating in invasion by the Great Heathen Army in 865. By 878, the Vikings had overrun East Anglia, Northumbria, and Mercia, and nearly conquered Wessex. The West Saxons fought back under Alfred the Great, and achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Edington.[8] Alfred and the Viking leader Guthrum agreed on a division that gave the Anglo-Saxons western Mercia, and eastern Mercia to the Vikings. In the 890s, renewed Viking attacks were successfully fought off by Alfred, assisted by his son (and Æthelstan's father) Edward and Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians. Æthelred ruled English Mercia under Alfred and was married to his daughter Æthelflæd. Alfred died in 899 and was succeeded by Edward. Æthelwold, the son of Æthelred, King Alfred's older brother and predecessor as king, made a bid for power, but was killed at the Battle of the Holme in 902.[9]

Little is known of warfare between the English and the Danes over the next few years, but in 909, Edward sent a West Saxon and Mercian army to ravage Northumbria. The following year the Northumbrian Danes attacked Mercia, but suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Tettenhall.[10] Æthelred died in 911 and was succeeded as ruler of Mercia by his widow Æthelflæd. Over the next decade, Edward and Æthelflæd conquered Viking Mercia and East Anglia. Æthelflæd died in 918 and was briefly succeeded by her daughter Ælfwynn, but in the same year Edward deposed her and took direct control of Mercia.[11]

When Edward died in 924, he controlled all of England south of the Humber.[11] The Viking king Sihtric ruled the Kingdom of York in southern Northumbria, but Ealdred maintained Anglo-Saxon rule in at least part of the former kingdom of Bernicia from his base in Bamburgh in northern Northumbria. Constantine II ruled Scotland, apart from the southwest, which was the British Kingdom of Strathclyde. Wales was divided into a number of small kingdoms, including Deheubarth in the southwest, Gwent in the southeast, Brycheiniog immediately north of Gwent, and Gwynedd in the north.[12]

Early life

According to the Anglo-Norman historian William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan was thirty years old when he came to the throne in 924, which would mean that he was born around 894. He was the oldest son of Edward the Elder. He was Edward's only son by his first consort, Ecgwynn. Very little is known about Ecgwynn, and she is not named in any contemporary source. Medieval chroniclers gave varying descriptions of her rank: one described her as an ignoble consort of inferior birth, while others described her birth as noble.[13] Modern historians also disagree about her status. Simon Keynes and Richard Abels believe that leading figures in Wessex were unwilling to accept Æthelstan as king in 924 partly because his mother had been Edward the Elder's concubine.[14] However, Barbara Yorke and Sarah Foot argue that allegations that Æthelstan was illegitimate were a product of the dispute over the succession, and that there is no reason to doubt that she was Edward's legitimate wife.[15] She may have been related to St Dunstan.[16]

William of Malmesbury wrote that Alfred the Great honoured his young grandson with a ceremony in which he gave him a scarlet cloak, a belt set with gems, and a sword with a gilded scabbard.[17] Medieval Latin scholar Michael Lapidge and historian Michael Wood see this as designating Æthelstan as a potential heir at a time when the claim of Alfred's nephew, Æthelwold, to the throne represented a threat to the succession of Alfred's direct line,[18] but historian Janet Nelson suggests that it should be seen in the context of conflict between Alfred and Edward in the 890s, and might reflect an intention to divide the realm between his son and his grandson after his death.[19] Historian Martin Ryan goes further, suggesting that at the end of his life Alfred may have favoured Æthelstan rather than Edward as his successor.[20] An acrostic poem praising prince "Adalstan", and prophesying a great future for him, has been interpreted by Lapidge as referring to the young Æthelstan, punning on the Old English meaning of his name, "noble stone".[21] Lapidge and Wood see the poem as a commemoration of Alfred's ceremony by one of his leading scholars, John the Old Saxon.[22] In Michael Wood's view, the poem confirms the truth of William of Malmesbury's account of the ceremony. Wood also suggests that Æthelstan may have been the first English king to be groomed from childhood as an intellectual, and that John was probably his tutor.[23] However, Sarah Foot argues that the acrostic poem makes better sense if it is dated to the beginning of Æthelstan's reign.[24]

Edward married his second wife, Ælfflæd, at about the time of his father's death, probably because Ecgwynn had died, although she may have been put aside. The new marriage weakened Æthelstan's position, as his step-mother naturally favoured the interests of her own sons, Ælfweard and Edwin.[17] By 920 Edward had taken a third wife, Eadgifu, probably after putting Ælfflæd aside.[25] Eadgifu also had two sons, the future kings Edmund and Eadred. Edward had several daughters, perhaps as many as nine.[26]

Æthelstan's later education was probably at the Mercian court of his aunt and uncle, Æthelflæd and Æthelred, and it is likely the young prince gained his military training in the Mercian campaigns to conquer the Danelaw. According to a transcript dating from 1304, in 925 Æthelstan gave a charter of privileges to St Oswald's Priory, Gloucester, where his aunt and uncle were buried, "according to a pact of paternal piety which he formerly pledged with Æthelred, ealdorman of the people of the Mercians".[27] When Edward took direct control of Mercia after Æthelflæd's death in 918, Æthelstan may have represented his father's interests there.[28]

Reign

The struggle for power

Edward died at Farndon in northern Mercia on 17 July 924, and the ensuing events are unclear.[29] Ælfweard, Edward's eldest son by Ælfflæd, had ranked above Æthelstan in attesting a charter in 901, and Edward may have intended Ælfweard to be his successor as king, either of Wessex only or of the whole kingdom. If Edward had intended his realms to be divided after his death, his deposition of Ælfwynn in Mercia in 918 may have been intended to prepare the way for Æthelstan's succession as king of Mercia.[30] When Edward died, Æthelstan was apparently with him in Mercia, while Ælfweard was in Wessex. Mercia acknowledged Æthelstan as king, and Wessex may have chosen Ælfweard. However, Ælfweard outlived his father by only sixteen days.[31]

Even after Ælfweard's death there seems to have been opposition to Æthelstan in Wessex, particularly in Winchester, where Ælfweard was buried. At first Æthelstan behaved as a Mercian king. A charter relating to land in Derbyshire, which appears to have been issued at a time in 925 when his authority had not yet been recognised outside Mercia, was witnessed only by Mercian bishops.[32] In the view of historians David Dumville and Janet Nelson he may have agreed not to marry or have heirs in order to gain acceptance.[33] However, Sarah Foot ascribes his decision to remain unmarried to "a religiously motivated determination on chastity as a way of life".[34][lower-alpha 2]

The coronation of Æthelstan took place on 4 September 925 at Kingston upon Thames, perhaps due to its symbolic location on the border between Wessex and Mercia.[36] He was crowned by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Athelm, who probably designed or organised a new ordo (religious order of service) in which the king wore a crown for the first time instead of a helmet. The new ordo was influenced by West Frankish liturgy and in turn became one of the sources of the medieval French ordo.[37]

Opposition seems to have continued even after the coronation. According to William of Malmesbury, an otherwise unknown nobleman called Alfred plotted to blind Æthelstan on account of his supposed illegitimacy, although it is unknown whether he aimed to make himself king or was acting on behalf of Edwin, Ælfweard's younger brother. Blinding would have been a sufficient disability to render Æthelstan ineligible for kingship without incurring the odium attached to murder.[38] Tensions between Æthelstan and Winchester seem to have continued for some years. The Bishop of Winchester, Frithestan, did not attend the coronation or witness any of Æthelstan's known charters until 928. After that he witnessed fairly regularly until his resignation in 931, but was listed in a lower position than he was entitled to by his seniority.[39]

In 933 Edwin was drowned in a shipwreck in the North Sea. His cousin, Adelolf, Count of Boulogne, took his body for burial at the Abbey of Saint Bertin in Saint-Omer. According to the abbey's annalist, Folcuin—who wrongly believed that Edwin had been king—thought he had fled England "driven by some disturbance in his kingdom". Folcuin stated that Æthelstan sent alms to the abbey for his dead brother and received monks from the abbey graciously when they came to England, although Folcuin did not realise that Æthelstan died before the monks made the journey in 944. The twelfth-century chronicler Symeon of Durham said that Æthelstan ordered Edwin to be drowned, but this is dismissed by most historians.[lower-alpha 3] Edwin might have fled England after an unsuccessful rebellion against his brother's rule, and his death may have put an end to Winchester's opposition.[41]

King of the English

Edward the Elder had conquered the Danish territories in east Mercia and East Anglia with the assistance of Æthelflæd and her husband Æthelred, but when Edward died the Danish king Sihtric still ruled the Viking Kingdom of York (formerly the southern Northumbrian kingdom of Deira). In January 926, Æthelstan arranged for his only full sister to marry Sihtric. The two kings agreed not to invade each other's territories or to support each other's enemies. The following year Sihtric died, and Æthelstan seized the chance to invade.[lower-alpha 4] Guthfrith, a cousin of Sihtric, led a fleet from Dublin to try to take the throne, but Æthelstan easily prevailed. He captured York and received the submission of the Danish people. According to a southern chronicler, he "succeeded to the kingdom of the Northumbrians", and it is uncertain whether he had to fight Guthfrith.[45] Southern kings had never ruled the north, and his usurpation was met with outrage by the Northumbrians, who had always resisted southern control. However, at Eamont, near Penrith, on 12 July 927, King Constantine II of Alba, King Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, Ealdred of Bamburgh, and King Owain of Strathclyde (or Morgan ap Owain of Gwent)[lower-alpha 5] accepted Æthelstan's overlordship. His triumph led to seven years of peace in the north.[47]

Whereas Æthelstan was the first English king to achieve lordship over northern Britain, he inherited his authority over the Welsh kings from his father and aunt. In the 910s Gwent acknowledged the lordship of Wessex, and Deheubarth and Gwynedd accepted that of Æthelflæd; following Edward's takeover of Mercia, they transferred their allegiance to him. According to William of Malmesbury, after the meeting at Eamont Æthelstan summoned the Welsh kings to Hereford, where he imposed a heavy annual tribute and fixed the border between England and Wales in the Hereford area at the River Wye.[48][lower-alpha 6] The dominant figure in Wales was Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, described by the historian of early medieval Wales Thomas Charles-Edwards as "the firmest ally of the 'emperors of Britain' among all the kings of his day". Welsh kings attended Æthelstan's court between 928 and 935 and witnessed charters at the head of the list of laity (apart from the kings of Scotland and Strathclyde), showing that their position was regarded as superior to that of the other great men present. The alliance produced peace between Wales and England, and within Wales, lasting throughout Æthelstan's reign, though some Welsh resented the status of their rulers as under-kings, as well as the high level of tribute imposed upon them. In Armes Prydein Vawr (The Great Prophecy of Britain), a Welsh poet foresaw the day when the British would rise up against their Saxon oppressors and drive them into the sea.[50]

According to William of Malmesbury, after the Hereford meeting Æthelstan went on to expel the Cornish from Exeter, fortify its walls, and fix the Cornish boundary at the River Tamar. This account is regarded sceptically by historians, however, as Cornwall had been under English rule since the mid-ninth century. Thomas Charles-Edwards describes it as "an improbable story", while historian John Reuben Davies sees it as the suppression of a British revolt and the confinement of the Cornish beyond the Tamar. Æthelstan emphasised his control by establishing a new Cornish see and appointing its first bishop, but Cornwall kept its own culture and language.[51]

_obverse.jpg.webp)

Æthelstan became the first king of all the Anglo-Saxon peoples, and in effect overlord of Britain.[52][lower-alpha 7] His successes inaugurated what John Maddicott, in his history of the origins of the English Parliament, calls the imperial phase of English kingship between about 925 and 975, when rulers from Wales and Scotland attended the assemblies of English kings and witnessed their charters.[54] Æthelstan tried to reconcile the aristocracy in his new territory of Northumbria to his rule. He lavished gifts on the minsters of Beverley, Chester-le-Street and York, emphasising his Christianity. He also purchased the vast territory of Amounderness in Lancashire, and gave it to the Archbishop of York, his most important lieutenant in the region.[lower-alpha 8] But he remained a resented outsider, and the northern British kingdoms preferred to ally with the pagan Norse of Dublin. In contrast to his strong control over southern Britain, his position in the north was far more tenuous.[56]

Invasion of Scotland in 934

In 934 Æthelstan invaded Scotland. His reasons are unclear, and historians give alternative explanations. The death of his half-brother Edwin in 933 might have finally removed factions in Wessex opposed to his rule. Guthfrith, the Norse king of Dublin who had briefly ruled Northumbria, died in 934; any resulting insecurity among the Danes would have given Æthelstan an opportunity to stamp his authority on the north. An entry in the Annals of Clonmacnoise, recording the death in 934 of a ruler who was possibly Ealdred of Bamburgh, suggests another possible explanation. This points to a dispute between Æthelstan and Constantine over control of his territory. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle briefly recorded the expedition without explanation, but the twelfth-century chronicler John of Worcester stated that Constantine had broken his treaty with Æthelstan.[57]

Æthelstan set out on his campaign in May 934, accompanied by four Welsh kings: Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, Idwal Foel of Gwynedd, Morgan ap Owain of Gwent, and Tewdwr ap Griffri of Brycheiniog. His retinue also included eighteen bishops and thirteen earls, six of whom were Danes from eastern England. By late June or early July he had reached Chester-le-Street, where he made generous gifts to the tomb of St Cuthbert, including a stole and maniple (ecclesiastical garments) originally commissioned by his step-mother Ælfflæd as a gift to Bishop Frithestan of Winchester. The invasion was launched by land and sea. According to Symeon of Durham, his land forces ravaged as far as Dunnottar in north-east Scotland, the furthest north that any English army had reached since Ecgfrith's disastrous invasion in 685, while the fleet raided Caithness, then probably part of the Norse kingdom of Orkney.[58]

No battles are recorded during the campaign, and chronicles do not record its outcome. By September, however, he was back in the south of England at Buckingham, where Constantine witnessed a charter as subregulus, thus acknowledging Æthelstan's overlordship. In 935 a charter was attested by Constantine, Owain of Strathclyde, Hywel Dda, Idwal Foel, and Morgan ap Owain. At Christmas of the same year Owain of Strathclyde was once more at Æthelstan's court along with the Welsh kings, but Constantine was not. His return to England less than two years later would be in very different circumstances.[59]

Battle of Brunanburh

In 934 Olaf Guthfrithson succeeded his father Guthfrith as the Norse King of Dublin. The alliance between the Norse and the Scots was cemented by the marriage of Olaf to Constantine's daughter. By August 937 Olaf had defeated his rivals for control of the Viking part of Ireland, and he promptly launched a bid for the former Norse kingdom of York. Individually Olaf and Constantine were too weak to oppose Æthelstan, but together they could hope to challenge the dominance of Wessex. In the autumn they joined with the Strathclyde Britons under Owain to invade England. Medieval campaigning was normally conducted in the summer, and Æthelstan could hardly have expected an invasion on such a large scale so late in the year. He seems to have been slow to react, and an old Latin poem preserved by William of Malmesbury accused him of having "languished in sluggish leisure". The allies plundered English territory while Æthelstan took his time gathering a West Saxon and Mercian army. However, Michael Wood praises his caution, arguing that unlike Harold in 1066, he did not allow himself to be provoked into precipitate action. When he marched north, the Welsh did not join him, and they did not fight on either side.[60]

The two sides met at the Battle of Brunanburh, resulting in an overwhelming victory for Æthelstan, supported by his young half-brother, the future King Edmund. Olaf escaped back to Dublin with the remnant of his forces, while Constantine lost a son. The English also suffered heavy losses, including two of Æthelstan's cousins, sons of Edward the Elder's younger brother, Æthelweard.[61]

The battle was reported in the Annals of Ulster:

A great, lamentable and horrible battle was cruelly fought between the Saxons and the Northmen, in which several thousands of Northmen, who are uncounted, fell, but their king Amlaib [Olaf], escaped with a few followers. A large number of Saxons fell on the other side, but Æthelstan, king of the Saxons, enjoyed a great victory.[62]

A generation later, the chronicler Æthelweard reported that it was popularly remembered as "the great battle", and it sealed Æthelstan's posthumous reputation as "victorious because of God" (in the words of the homilist Ælfric of Eynsham).[63] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle abandoned its usual terse style in favour of a heroic poem vaunting the great victory, employing imperial language to present Æthelstan as ruler of an empire of Britain.[64] The site of the battle is uncertain, however, and over thirty sites have been suggested, with Bromborough on the Wirral the most favoured among historians.[65]

Historians disagree over the significance of the battle. Alex Woolf describes it as a "pyrrhic victory" for Æthelstan: the campaign seems to have ended in a stalemate, his power appears to have declined, and after he died Olaf acceded to the kingdom of Northumbria without resistance.[66] Alfred Smyth describes it as "the greatest battle in Anglo-Saxon history", but he also states that its consequences beyond Æthelstan's reign have been overstated.[67] In the view of Sarah Foot, on the other hand, it would be difficult to exaggerate the battle's importance: if the Anglo-Saxons had been defeated, their hegemony over the whole mainland of Britain would have disintegrated.[68]

Kingship

Administration

Anglo-Saxon kings ruled through ealdormen, who had the highest lay status under the king. In ninth-century Wessex they each ruled a single shire, but by the middle of the tenth they had authority over a much wider area, a change probably introduced by Æthelstan to deal with the problems of governing his extended realm.[69] One of the ealdormen, who was also called Æthelstan, governed the eastern Danelaw territory of East Anglia, the largest and wealthiest province of England. He became so powerful that he was later known as Æthelstan Half King.[70] Several of the ealdormen who witnessed charters had Scandinavian names, and while the localities they came from cannot be identified, they were almost certainly the successors of the earls who led Danish armies in the time of Edward the Elder, and who were retained by Æthelstan as his representatives in local government.[71]

Beneath the ealdormen, reeves—royal officials who were noble local landowners—were in charge of a town or royal estate. The authority of church and state was not separated in early medieval societies, and the lay officials worked closely with their diocesan bishop and local abbots, who also attended the king's royal councils.[72]

As the first king of all the Anglo-Saxon peoples, Æthelstan needed effective means to govern his extended realm. Building on the foundations of his predecessors, he created the most centralised government that England had yet seen.[73] Previously, some charters had been produced by royal priests and others by members of religious houses, but between 928 and 935 they were produced exclusively by a scribe known to historians as "Æthelstan A", showing an unprecedented degree of royal control over an important activity. Unlike earlier and later charters, "Æthelstan A" provides full details of the date and place of adoption and an unusually long witness list, providing crucial information for historians. After "Æthelstan A" retired or died, charters reverted to a simpler form, suggesting that they had been the work of an individual, rather than the development of a formal writing office.[74]

A key mechanism of government was the king's council (witan in Old English).[75] Anglo-Saxon kings did not have a fixed capital city. Their courts were peripatetic, and their councils were held at varying locations around their realms. Æthelstan stayed mainly in Wessex, however, and controlled outlying areas by summoning leading figures to his councils. The small and intimate meetings that had been adequate until the enlargement of the kingdom under Edward the Elder gave way to large bodies attended by bishops, ealdormen, thegns, magnates from distant areas, and independent rulers who had submitted to his authority. Frank Stenton sees Æthelstan's councils as "national assemblies", which did much to break down the provincialism that was a barrier to the unification of England. John Maddicott goes further, seeing them as the start of centralised assemblies that had a defined role in English government, and Æthelstan as "the true if unwitting founder of the English parliament".[76]

Law

The Anglo-Saxons were the first people in northern Europe to write administrative documents in the vernacular, and law codes in Old English go back to Æthelberht of Kent at the beginning of the seventh century. The law code of Alfred the Great, from the end of the ninth century, was also written in the vernacular, and he expected his ealdormen to learn it.[77] His code was strongly influenced by Carolingian law going back to Charlemagne in such areas as treason, peace-keeping, organisation of the hundreds and judicial ordeal.[78] It remained in force throughout the tenth century, and Æthelstan's codes were built on this foundation.[79] Legal codes required the approval of the king, but they were treated as guidelines which could be adapted and added to at the local level, rather than a fixed canon of regulations, and customary oral law was also important in the Anglo-Saxon period.[80]

More legal texts survive from Æthelstan's reign than from any other tenth-century English king. The earliest appear to be his tithe edict and the "Ordinance on Charities". Four legal codes were adopted at Royal Councils in the early 930s at Grately in Hampshire, Exeter, Faversham in Kent, and Thunderfield in Surrey. Local legal texts survive from London and Kent, and one concerning the 'Dunsæte' on the Welsh border probably also dates to Æthelstan's reign.[81] In the view of the historian of English law Patrick Wormald, the laws must have been written by Wulfhelm, who succeeded Athelm as Archbishop of Canterbury in 926.[82] [lower-alpha 9] Other historians see Wulfhelm's role as less important, giving the main credit to Æthelstan himself, although the significance placed on the ordeal as an ecclesiastical ritual shows the increased influence of the church. Nicholas Brooks sees the role of the bishops as marking an important stage in the increasing involvement of the church in the making and enforcement of law.[84]

The two earliest codes were concerned with clerical matters, and Æthelstan stated that he acted on the advice of Wulfhelm and his bishops. The first asserts the importance of paying tithes to the church. The second enforces the duty of charity on Æthelstan's reeves, specifying the amount to be given to the poor and requiring reeves to free one penal slave annually. His religious outlook is shown in a wider sacralisation of the law in his reign.[85]

The later codes show his concern with threats to social order, especially robbery, which he regarded as the most important manifestation of social breakdown. The first of these later codes, issued at Grately, prescribed harsh penalties, including the death penalty for anyone over twelve years old caught in the act of stealing goods worth more than eight pence. This apparently had little effect, as Æthelstan admitted in the Exeter code: "I King Æthelstan, declare that I have learned that the public peace has not been kept to the extent, either of my wishes, or of the provisions laid down at Grately, and my councillors say that I have suffered this too long." In desperation the Council tried a different strategy, offering an amnesty to thieves if they paid compensation to their victims. The problem of powerful families protecting criminal relatives was to be solved by expelling them to other parts of the realm. This strategy did not last long, and at Thunderfield Æthelstan returned to the hard line, softened by raising the minimum age for the death penalty to fifteen "because he thought it too cruel to kill so many young people and for such small crimes as he understood to be the case everywhere".[86] His reign saw the first introduction of the system of tithing, sworn groups of ten or more men who were jointly responsible for peacekeeping (later known as frankpledge). Sarah Foot commented that tithing and oath-taking to deal with the problem of theft had its origin in Frankia: "But the equation of theft with disloyalty to Æthelstan's person appears peculiar to him. His preoccupation with theft—tough on theft, tough on the causes of theft—finds no direct parallel in other kings' codes."[87]

Historians differ widely regarding Æthelstan's legislation. Patrick Wormald's verdict was harsh: "The hallmark of Æthelstan's law-making is the gulf dividing its exalted aspirations from his spasmodic impact." In his view, "The legislative activity of Æthelstan's reign has rightly been dubbed 'feverish' ... But the extant results are, frankly, a mess.[88] In the view of Simon Keynes, however, "Without any doubt the most impressive aspect of King Æthelstan's government is the vitality of his law-making", which shows him driving his officials to do their duties and insisting on respect for the law, but also demonstrates the difficulty he had in controlling a troublesome people. Keynes sees the Grately code as "an impressive piece of legislation" showing the king's determination to maintain social order.[89]

Coinage

In the 970s, Æthelstan's nephew, King Edgar, reformed the monetary system to give Anglo-Saxon England the most advanced currency in Europe, with a good quality silver coinage, which was uniform and abundant.[90] In Æthelstan's time, however, it was far less developed, and minting was still organised regionally long after Æthelstan unified the country. The Grately code included a provision that there was to be only one coinage across the king's dominion. However, this is in a section that appears to be copied from a code of his father, and the list of towns with mints is confined to the south, including London and Kent, but not northern Wessex or other regions. Early in Æthelstan's reign, different styles of coin were issued in each region, but after he conquered York and received the submission of the other British kings, he issued a new coinage, known as the "circumscription cross" type. This advertised his newly exalted status with the inscription, "Rex Totius Britanniae". Examples were minted in Wessex, York, and English Mercia (in Mercia bearing the title "Rex Saxorum"), but not in East Anglia or the Danelaw.[91]

In the early 930s a new coinage was issued, the "crowned bust" type, with the king shown for the first time wearing a crown with three stalks. This was eventually issued in all regions apart from Mercia, which issued coins without a ruler portrait, suggesting, in Sarah Foot's view, that any Mercian affection for a West Saxon king brought up among them quickly declined.[92]

Church

Church and state maintained close relations in the Anglo-Saxon period, both socially and politically. Churchmen attended royal feasts as well as meetings of the Royal Council. During Æthelstan's reign these relations became even closer, especially as the archbishopric of Canterbury had come under West Saxon jurisdiction since Edward the Elder annexed Mercia, and Æthelstan's conquests brought the northern church under the control of a southern king for the first time.[93]

Æthelstan appointed members of his own circle to bishoprics in Wessex, possibly to counter the influence of the Bishop of Winchester, Frithestan. One of the king's mass-priests (priests employed to say Mass in his household), Ælfheah, became Bishop of Wells, while another, Beornstan, succeeded Frithestan as Bishop of Winchester. Beornstan was succeeded by another member of the royal household, also called Ælfheah.[94] Two of the leading figures in the later tenth-century Benedictine monastic reform in Edgar's reign, Dunstan and Æthelwold, served in early life at Æthelstan's court and were ordained as priests by Ælfheah of Winchester at the king's request.[95] According to Æthelwold's biographer, Wulfstan, "Æthelwold spent a long period in the royal palace in the king's inseparable companionship and learned much from the king's wise men that was useful and profitable to him".[96] Oda, a future Archbishop of Canterbury, was also close to Æthelstan, who appointed him Bishop of Ramsbury.[97] Oda may have been present at the battle of Brunanburh.[98]

Æthelstan was a noted collector of relics, and while this was a common practice at the time, he was marked out by the scale of his collection and the refinement of its contents.[99] The abbot of Saint Samson in Dol sent him some as a gift, and in his covering letter he wrote: "we know you value relics more than earthly treasure".[100] Æthelstan was also a generous donor of manuscripts and relics to churches and monasteries. His reputation was so great that some monastic scribes later falsely claimed that their institutions had been beneficiaries of his largesse. He was especially devoted to the cult of St. Cuthbert in Chester-le-Street, and his gifts to the community there included Bede's Lives of Cuthbert. He commissioned it especially to present to Chester-le Street, and out of all manuscripts he gave to a religious foundation which survive, it is the only one which was wholly written in England during his reign.[101] It has a portrait of Æthelstan presenting the book to Cuthbert, the earliest surviving manuscript portrait of an English king.[102] In the view of Janet Nelson, his "rituals of largesse and devotion at sites of supernatural power ... enhanced royal authority and underpinned a newly united imperial realm".[100]

Æthelstan had a reputation for founding churches, although it is unclear how justified this is. According to late and dubious sources, these churches included minsters at Milton Abbas in Dorset and Muchelney in Somerset. In the view of historian John Blair, the reputation is probably well-founded, but "these waters are muddied by Æthelstan's almost folkloric reputation as a founder, which made him a favourite hero of later origin-myths".[103] However, while he was a generous donor to monasteries, he did not give land for new ones or attempt to revive the ones in the north and east destroyed by Viking attacks.[104]

He also sought to build ties with continental churches. Cenwald was a royal priest before his appointment as Bishop of Worcester, and in 929 he accompanied two of Æthelstan's half-sisters to the Saxon court so that the future Holy Roman Emperor, Otto, could choose one of them as his wife. Cenwald went on to make a tour of German monasteries, giving lavish gifts on Æthelstan's behalf and receiving in return promises that the monks would pray for the king and others close to him in perpetuity. England and Saxony became closer after the marriage alliance, and German names start to appear in English documents, while Cenwald kept up the contacts he had made by subsequent correspondence, helping the transmission of continental ideas about reformed monasticism to England.[105]

Learning

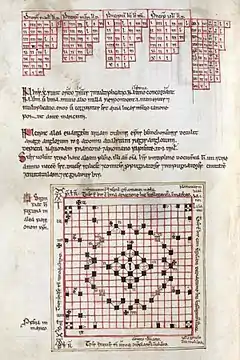

Æthelstan built on his grandfather's efforts to revive ecclesiastical scholarship, which had fallen to a low state in the second half of the ninth century. John Blair described Æthelstan's achievement as "a determined reconstruction, visible to us especially through the circulation and production of books, of the shattered ecclesiastical culture".[106] He was renowned in his own day for his piety and promotion of sacred learning. His interest in education, and his reputation as a collector of books and relics, attracted a cosmopolitan group of ecclesiastical scholars to his court, particularly Bretons and Irish. Æthelstan gave extensive aid to Breton clergy who had fled Brittany following its conquest by the Vikings in 919. He made a confraternity agreement with the clergy of Dol Cathedral in Brittany, who were then in exile in central France, and they sent him the relics of Breton saints, apparently hoping for his patronage. The contacts resulted in a surge in interest in England for commemorating Breton saints. One of the most notable scholars at Æthelstan's court was Israel the Grammarian, who may have been a Breton. Israel and "a certain Frank" drew a board game called "Gospel Dice" for an Irish bishop, Dub Innse, who took it home to Bangor. Æthelstan's court played a crucial role in the origins of the English monastic reform movement.[107]

Few prose narrative sources survive from Æthelstan's reign, but it produced an abundance of poetry, much of it Norse-influenced praise of the King in grandiose terms, such as the Brunanburh poem. Sarah Foot even makes a case that Beowulf may have been composed in Æthelstan's circle.[108]

Æthelstan's court was the centre of a revival of the elaborate hermeneutic style of later Latin writers, influenced by the West Saxon scholar Aldhelm (c. 639–709), and by early tenth-century French monasticism. Foreign scholars at Æthelstan's court such as Israel the Grammarian were practitioners. The style was characterised by long, convoluted sentences and a predilection for rare words and neologisms.[109] The "Æthelstan A" charters were written in hermeneutic Latin. In the view of Simon Keynes it is no coincidence that they first appear immediately after the king had for the first time united England under his rule, and they show a high level of intellectual attainment and a monarchy invigorated by success and adopting the trappings of a new political order.[110] The style influenced architects of the late tenth-century monastic reformers educated at Æthelstan's court such as Æthelwold and Dunstan, and became a hallmark of the movement.[111] After "Æthelstan A", charters became more simple, but the hermeneutic style returned in the charters of Eadwig and Edgar.[112]

The historian W. H. Stevenson commented in 1898:

The object of the compilers of these charters was to express their meaning by the use of the greatest possible number of words and by the choice of the most grandiloquent, bombastic words they could find. Every sentence is so overloaded by the heaping up of unnecessary words that the meaning is almost buried out of sight. The invocation with its appended clauses, opening with pompous and partly alliterative words, will proceed amongst a blaze of verbal fireworks throughout twenty lines of smallish type, and the pyrotechnic display will be maintained with equal magnificence throughout the whole charter, leaving the reader, dazzled by the glaze and blinded by the smoke, in a state of uncertainty as to the meaning of these frequently untranslatable and usually interminable sentences.[113]

However, Michael Lapidge argues that however unpalatable the hermeneutic style seems to modern taste, it was an important part of late Anglo-Saxon culture, and deserves more sympathetic attention than it has received from modern historians.[114] In the view of historian David Woodman, "Æthelstan A" should "be accorded recognition as an individual author of no little genius, a man who not only overhauled the legal form of the diploma but also had the ability to write Latin that is as enduringly fascinating as it is complex ... In many ways the diplomas of "Æthelstan A" represent the stylistic peak of the Anglo-Saxon diplomatic tradition, a fitting complement to Æthelstan's own momentous political feats and to the forging of what would become England."[115]

British monarch

Historians frequently comment on Æthelstan's grand and extravagant titles. On his coins and charters he is described as Rex totius Britanniae, or "King of the whole of Britain". A gospel book he donated to Christ Church, Canterbury is inscribed "Æthelstan, king of the English and ruler of the whole of Britain with a devout mind gave this book to the primatial see of Canterbury, to the church dedicated to Christ". In charters from 931 he is "king of the English, elevated by the right hand of the almighty to the throne of the whole kingdom of Britain", and in one manuscript dedication he is even styled "basileus et curagulus", the titles of Byzantine emperors.[116] Some historians are not impressed. "Clearly", comments Alex Woolf, "King Æthelstan was a man who had pretensions,"[117] while in the view of Simon Keynes, "Æthelstan A" proclaimed his master king of Britain "by wishful extension".[118] But according to George Molyneaux "this is to apply an anachronistic standard: tenth-century kings had a loose but real hegemony throughout the island, and their titles only appear inflated if one assumes that kingship ought to involve domination of an intensity like that seen within the English kingdom of the eleventh and later centuries."[119]

European relations

The West Saxon court had connections with the Carolingians going back to the marriage between Æthelstan's great-grandfather Æthelwulf and Judith, daughter of the king of West Francia (and future Holy Roman Emperor) Charles the Bald, as well as the marriage of Alfred the Great's daughter Ælfthryth to Judith's son by a later marriage, Baldwin II, Count of Flanders. One of Æthelstan's half-sisters, Eadgifu, married Charles the Simple, king of the West Franks, in the late 910s. He was deposed in 922, and Eadgifu sent their son Louis to safety in England. By Æthelstan's time the connection was well established, and his coronation was performed with the Carolingian ceremony of anointment, probably to draw a deliberate parallel between his rule and Carolingian tradition.[120] His "crowned bust" coinage of 933–938 was the first Anglo-Saxon coinage to show the king crowned, following Carolingian iconography.[121]

Like his father, Æthelstan was unwilling to marry his female relatives to his own subjects, so his sisters either entered nunneries or married foreign husbands. This was one reason for his close relations with European courts, and he married several of his half-sisters to European nobles[122] in what historian Sheila Sharp called "a flurry of dynastic bridal activity unequalled again until Queen Victoria's time".[123] Another reason lay in the common interest on both sides of the Channel in resisting the threat from the Vikings, while the rise in the power and reputation of the royal house of Wessex made marriage with an English princess more prestigious to European rulers.[124] In 926 Hugh, Duke of the Franks, sent Æthelstan's cousin, Adelolf, Count of Boulogne, on an embassy to ask for the hand of one of Æthelstan's sisters. According to William of Malmesbury, the gifts Adelolf brought included spices, jewels, many swift horses, a crown of solid gold, the sword of Constantine the Great, Charlemagne's lance, and a piece of the Crown of Thorns. Æthelstan sent his half-sister Eadhild to be Hugh's wife.[125]

Æthelstan's most important European alliance was with the new Liudolfing dynasty in East Francia. The Carolingian dynasty of East Francia had died out in the early tenth century, and its new Liudolfing king, Henry the Fowler, was seen by many as an arriviste. He needed a royal marriage for his son to establish his legitimacy, but no suitable Carolingian princesses were available. The ancient royal line of the West Saxons provided an acceptable alternative, especially as they (wrongly) claimed descent from the seventh-century king and saint, Oswald, who was venerated in Germany. In 929 or 930 Henry sent ambassadors to Æthelstan's court seeking a wife for his son, Otto, who later became Holy Roman Emperor. Æthelstan sent two of his half-sisters, and Otto chose Eadgyth. Fifty years later, Æthelweard, a descendant of Alfred the Great's older brother, addressed his Latin version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to Mathilde, Abbess of Essen, who was Eadgyth's granddaughter, and had apparently requested it. The other sister, whose name is uncertain, was married to a prince from near the Alps who has not definitely been identified.[126]

In early medieval Europe, it was common for kings to act as foster-fathers for the sons of other kings. Æthelstan was known for the support he gave to dispossessed young royalty. In 936 he sent an English fleet to help his foster-son, Alan II, Duke of Brittany, to regain his ancestral lands, which had been conquered by the Vikings. In the same year he assisted the son of his half-sister Eadgifu, Louis, to take the throne of West Francia, and in 939 he sent another fleet that unsuccessfully attempted to help Louis in a struggle with rebellious magnates. According to later Scandinavian sources, he helped another possible foster-son, Hakon, son of Harald Fairhair, king of Norway, to reclaim his throne,[127] and he was known among Norwegians as "Æthelstan the Good".[128]

Æthelstan's court was perhaps the most cosmopolitan of the Anglo-Saxon period.[129] The close contacts between the English and European courts ended soon after his death, but descent from the English royal house long remained a source of prestige for continental ruling families.[130] According to Frank Stenton in his history of the period, Anglo-Saxon England, "Between Offa and Cnut there is no English king who played so prominent or so sustained a part in the general affairs of Europe."[131]

Foreign contemporaries described him in panegyrical terms. The French chronicler Flodoard described him as "the king from overseas", and the Annals of Ulster as the "pillar of the dignity of the western world".[132] Some historians take a similar view. Michael Wood titled an essay, "The Making of King Aethelstan's Empire: an English Charlemagne?", and described him as "the most powerful ruler that Britain had seen since the Romans".[133] In the view of Veronica Ortenberg, he was "the most powerful ruler in Europe" with an army that had repeatedly defeated the Vikings; continental rulers saw him as a Carolingian emperor, who "was clearly treated as the new Charlemagne". She wrote:

Wessex kings carried an aura of power and success, which made them increasingly powerful in the 920s, while most Continental houses were in military trouble and engaged in internecine warfare. While the civil wars and the Viking attacks on the Continent had spelled the end of unity of the Carolingian empire, which had already disintegrated into separate kingdoms, military success had enabled Æthelstan to triumph at home and to attempt to go beyond the reputation of a great heroic dynasty of warrior kings, in order to develop a Carolingian ideology of kingship.[134]

Death

Æthelstan died at Gloucester on 27 October 939.[lower-alpha 10] His grandfather Alfred, his father Edward, and his half-brother Ælfweard had been buried at Winchester, but Æthelstan chose not to honour the city associated with opposition to his rule. By his own wish, he was buried at Malmesbury Abbey, where he had buried his cousins who died at Brunanburh. No other member of the West Saxon royal family was buried there, and, according to William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan's choice reflected his devotion to the abbey and to the memory of its seventh-century abbot Saint Aldhelm. William described Æthelstan as fair-haired "as I have seen for myself in his remains, beautifully intertwined with gold threads". His bones were later lost, but he is commemorated by an empty fifteenth-century tomb.[136]

Aftermath

After Æthelstan's death, the men of York immediately chose the Viking king of Dublin, Olaf Guthfrithson, as their king, and Anglo-Saxon control of the north, seemingly made safe by the victory of Brunanburh, collapsed. The reigns of Æthelstan's half-brothers Edmund (939–946) and Eadred (946–955) were largely devoted to regaining control. Olaf seized the east midlands, leading to the establishment of a frontier at Watling Street. In 941 Olaf died, and Edmund took back control of the east midlands in 942 and York in 944. Following Edmund's death, York again returned to Viking control, and it was only when the Northumbrians finally drove out their Norwegian Viking king, Eric Bloodaxe, in 954 and submitted to Eadred that Anglo-Saxon control of the whole of England was finally restored.[137]

Primary sources

Chronicle sources for the life of Æthelstan are limited, and the first biography, by Sarah Foot, was only published in 2011.[138] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in Æthelstan's reign is principally devoted to military events, and it is largely silent apart from recording his most important victories. An important source is the twelfth-century chronicle of William of Malmesbury, but historians are cautious about accepting his testimony, much of which cannot be verified from other sources. David Dumville goes so far as to dismiss William's account entirely, regarding him as a "treacherous witness" whose account is unfortunately influential.[139] However, Sarah Foot is inclined to accept Michael Wood's argument that William's chronicle draws on a lost life of Æthelstan. She cautions, however, that we have no means of discovering how far William "improved" on the original.[140]

In Dumville's view, Æthelstan has been regarded by historians as a shadowy figure because of an ostensible lack of source material, but he argues that the lack is more apparent than real.[141] Charters, law codes, and coins throw considerable light on Æthelstan's government.[142] The scribe known to historians as "Æthelstan A", who was responsible for drafting all charters between 928 and 935, provides very detailed information, including signatories, dates, and locations, illuminating Æthelstan's progress around his realm. "Æthelstan A" may have been Bishop Ælfwine of Lichfield, who was close to the king.[143] By contrast with this extensive source of information, no charters survive from 910 to 924, a gap which historians struggle to explain, and which makes it difficult to assess the degree of continuity in personnel and the operation of government between the reigns of Edward and Æthelstan.[144] Historians are also paying increasing attention to less conventional sources, such as contemporary poetry in his praise and manuscripts associated with his name.[145]

Legacy

The reign of Æthelstan has been overshadowed by the achievements of his grandfather, Alfred the Great, but he is now considered one of the greatest kings of the West Saxon dynasty.[146] Modern historians endorse the view of twelfth-century chronicler William of Malmesbury that "no one more just or more learned ever governed the kingdom".[147] Frank Stenton and Simon Keynes both describe him as the one Anglo-Saxon king who will bear comparison with Alfred. In Keynes's view he "has long been regarded, with good reason, as a towering figure in the landscape of the tenth century ... he has also been hailed as the first king of England, as a statesman of international standing".[148] David Dumville describes Æthelstan as "the father of mediaeval and modern England",[149] while Michael Wood regards Offa, Alfred, and Æthelstan as the three greatest Anglo-Saxon kings, and Æthelstan as "one of the more important lay intellectuals in Anglo-Saxon history".[150]

Æthelstan is regarded as the first King of England by modern historians.[lower-alpha 11] Although it was his successors who would achieve the permanent conquest of Viking York, Æthelstan's campaigns made this success possible.[146] His nephew Edgar called himself King of the English and revived the claim to rule over all the peoples of Britain. Simon Keynes argued that "the consistent usages of Edgar's reign represent nothing less than a determined reaffirmation of the polity created by Æthelstan in the 930s".[152] Historian Charles Insley, however, sees Æthelstan's hegemony as fragile: "The level of overlordship wielded by Æthelstan during the 930s over the rest of Britain was perhaps not attained again by an English king until Edward I."[153] George Molyneaux argues that:

The tendency of some modern historians to celebrate Æthelstan as "the first king of England" is, however, problematic, since there is little sign that in his day the title rex Anglorum was closely or consistently tied to an area similar to that which we consider England. When Æthelstan's rule was associated with any definite geographical expanse, the territory in question was usually the whole island of Britain.[154]

Simon Keynes saw Æthelstan's law-making as his greatest achievement.[79] His reign predates the sophisticated state of the later Anglo-Saxon period, but his creation of the most centralised government England had yet seen, with the king and his council working strategically to ensure acceptance of his authority and laws, laid the foundations on which his brothers and nephews would create one of the wealthiest and most advanced systems of government in Europe.[155] Æthelstan's reign built upon his grandfather's ecclesiastical programme, consolidating the ecclesiastical revival and laying the foundation for the monastic reform movement later in the century.[156]

Æthelstan's reputation was at its height when he died. According to Sarah Foot, "He found acclaim in his own day not only as a successful military leader and effective monarch but also as a man of devotion, committed to the promotion of religion and the patronage of learning." Later in the century, Æthelweard praised him as a very mighty king worthy of honour, and Æthelred the Unready, who named his eight sons after his predecessors, put Æthelstan first as the name of his eldest son.[157] In his biography of Æthelred, Levi Roach commented, "The king was clearly proud of his family and the fact that Æthelstan stands atop this list speaks volumes: though later overtaken by Alfred the Great in fame, in the 980s it must have seemed as if everything had begun with the king's great-uncle (a view with which many modern historians would be inclined to concur)."[158]

Memory of Æthelstan then declined until it was revived by William of Malmesbury, who took a special interest in him as the one king who had chosen to be buried in his own house. William's account kept his memory alive, and he was praised by other medieval chroniclers. In the early sixteenth century William Tyndale justified his English translation of the Bible by stating that he had read that King Æthelstan had caused the Holy Scriptures to be translated into Anglo-Saxon.[159] From the sixteenth century onwards, Alfred's reputation became dominant, and Æthelstan largely disappeared from popular consciousness. Sharon Turner's History of the Anglo-Saxons, first published between 1799 and 1805, played a crucial role in promoting Anglo-Saxon studies, and he helped to establish Brunanburh as a key battle in English history, but his treatment of Æthelstan was slight in comparison with Alfred. Charles Dickens had only one paragraph on Æthelstan in his Child's History of England, and although Anglo-Saxon history was a popular subject for nineteenth-century artists, and Alfred was frequently depicted in paintings at the Royal Academy between 1769 and 1904, there was not one picture of Æthelstan.[160]

Williams comments: "If Æthelstan has not had the reputation which accrued to his grandfather, the fault lies in the surviving sources; Æthelstan had no biographer, and the Chronicle for his reign is scanty. In his own day he was 'the roof-tree of the honour of the western world'."[161]

Notes

- Ninth-century kings of Wessex up to the reign of Alfred the Great used the title king of the West Saxons. In the 880s Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, accepted West Saxon lordship, and Alfred then adopted a new title, king of the Anglo-Saxons, representing his conception of a new polity of all the English people who were not under Viking rule. This endured until 927, when Æthelstan conquered the last Viking stronghold, York, and adopted the title king of the English.[5]

- An allusion in the twelfth-century Liber Eliensis to "Eadgyth, daughter of king Æthelstan" is probably a mistaken reference to his sister.[35]

- An exception is George Molyneaux, who states that "There are, however, grounds to suspect that Æthelstan may have had a hand in the death of Ælfweard's full brother Edwin in 933".[40]

- Some historians believe that Sihtric renounced his wife soon after the marriage and reverted to paganism,[42] while others merely state that Æthelstan took advantage of Sihtric's death to invade.[43] In the view of Alex Woolf, it is unlikely that Sihtric repudiated her because Æthelstan would almost certainly have declared war on him.[44]

- According to William of Malmesbury it was Owain of Strathclyde who was present at Eamont, but the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says Owain of Gwent. It could have been both.[46]

- William of Malmesbury's report of the Hereford meeting is not mentioned in the first volume of the Oxford History of Wales, Wales and the Britons 350–1064 by Thomas Charles-Edwards.[49]

- The situation in northern Northumbria, however, is unclear. In the view of Ann Williams, the submission of Ealdred of Bamburgh was probably nominal, and it is likely that he acknowledged Constantine as his lord, but Alex Woolf sees Ealdred as a semi-independent ruler acknowledging West Saxon authority, like Æthelred of Mercia a generation earlier.[53]

- In the view of Janet Nelson, Æthelstan had limited control over the north-west, and the donation of Amounderness in an area which had recently attracted many Scandinavian immigrants to "a powerful, but far from reliable, local potentate" was "a political gesture rather than a sign of prior control."[55]

- Wormald discusses the codes in detail in The Making of English Law.[83]

- Murray Beaven commented in 1918 that as the Anglo-Saxon day started at 4 p.m. the previous evening it is more likely that he died on 26 October, but as the exact date is not known Beaven preferred to keep the accepted date.[135]

- David Dumville's chapter on Æthelstan in Wessex and England is headed 'Between Alfred the Great and Edgar the Peacemaker: Æthelstan, The First King of England', and the title of Sarah Foot's biography is Æthelstan: The First King of England.[151]

Citations

- Foot 2011, pp. 120–121.

- Blunt 1974, pp. 47–48.

- Parker Library 2015.

- Foot 2011, p. 110.

- Keynes 2014, pp. 534–536.

- Wood 2005, p. 7.

- Stenton 1971, pp. 95, 236.

- Keynes & Lapidge 1983, pp. 11–13, 16–23.

- Stenton 1971, pp. 259–269, 321–322.

- Miller 2004.

- Costambeys 2004.

- Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 510–512, 548.

- Foot 2011, pp. 29–30.

- Keynes 1999, p. 467; Abels 1998, p. 307.

- Yorke 2001, pp. 26, 33; Foot 2011, pp. 29–31.

- Yorke 2004.

- Foot 2011, pp. 31–33.

- Lapidge 1993, p. 68 n. 96; Wood 1999, pp. 157–158.

- Nelson 1999a, pp. 63–64.

- Ryan 2013, p. 296.

- Lapidge 1993, pp. 60–68.

- Lapidge 1993, p. 69; Wood 1999, p. 158.

- Wood 1999, p. 157; Wood 2007, p. 199; Wood 2010, p. 137.

- Foot 2011, pp. 32, 110–112.

- Williams 1991a, p. 6; Miller 2004.

- Foot 2011, pp. xv, 44–52.

- Foot 2011, pp. 17, 34–36, 206.

- Foot 2011a.

- Foot 2011, p. 17.

- Keynes 2001, p. 51; Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 510.

- Foot 2011, p. 17; Keynes 2014, pp. 535–536; Keynes 1985, p. 187 n. 206.

- Foot 2011, pp. 73–74; Keynes 1999, pp. 467–468.

- Dumville 1992, p. 151; Nelson 1999b, p. 104.

- Foot 2011, p. 249.

- Foot 2011, p. 59.

- Foot 2011, pp. 73–74.

- Nelson 2008, pp. 125–126.

- Foot 2011, p. 40.

- Foot 2011, pp. 75, 83 n. 98; Thacker 2001, pp. 254–255.

- Molyneaux 2015, p. 29.

- Foot 2011, pp. 39–43, 86–87; Stenton 1971, pp. 355–356.

- Hart 2004; Thacker 2001, p. 257.

- Foot 2011, p. 18; Stenton 1971, p. 340; Miller 2014, p. 18.

- Woolf 2007, pp. 150–151.

- Foot 2011, pp. 12–19, 48.

- Foot 2011, p. 162 n. 15; Woolf 2007, p. 151; Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 511–512.

- Higham 1993, p. 190; Foot 2011, p. 20.

- Stenton 1971, pp. 340–41; Foot 2011, p. 163.

- Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 510–519.

- Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 497–523.

- Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 432; Davies 2013, pp. 342–343; Foot 2011, p. 164; Stenton 1971, pp. 341–342.

- Foot 2011, p. 20.

- Williams 1991c, pp. 116–117; Woolf 2007, p. 158.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 7–8, 13.

- Nelson 1999b, pp. 116–117.

- Higham 1993, p. 192; Keynes 1999, p. 469.

- Foot 2011, pp. 164–65; Woolf 2007, pp. 158–165.

- Foot 2011, pp. 87–88, 122–123, 165–167; Woolf 2007, pp. 158–166; Hunter Blair 2003, p. 46.

- Foot 2011, pp. 88–89; Woolf 2007, pp. 166–168.

- Higham 1993, p. 193; Livingston 2011, pp. 13–18, 23; Wood 1999, p. 166; Wood 2005, p. 158.

- Foot 2011, pp. 169–171; Stenton 1971, pp. 342–343; Woolf 2007, pp. 168–169; Smyth 1979, pp. 202–204.

- Woolf 2007, p. 169.

- Foot 2011, pp. 3, 210–211.

- Foot 2008, p. 144.

- Foot 2011, pp. 172–179; Scragg 2014, p. 58; Higham 1993, p. 193; Hill 2004, pp. 139–153; Livingston 2011, pp. 18–20.

- Woolf 2013, p. 256.

- Smyth 1984, p. 204; Smyth 1979, p. 63.

- Foot 2011, pp. 172–172.

- John 1982, p. 172; Stafford 2014, pp. 156–157.

- Hart 1992, p. 575.

- Foot 2011, p. 129.

- Foot 2011, p. 130.

- Foot 2011, p. 10.

- Foot 2011, pp. 71–72.

- Yorke 2014, pp. 126–127.

- Foot 2011, pp. 63, 77–79; Stenton 1971, p. 352; Maddicott 2010, p. 4.

- Foot 2011, p. 136.

- Pratt 2010, p. 332.

- Keynes 1999, p. 471.

- Roach 2013, pp. 477–479; Foot 2011, pp. 136–137.

- Pratt 2010, pp. 335–336, 345–346; Foot 2011, pp. 299–300.

- Wormald 1999, pp. 299–300.

- Wormald 1999, pp. 290–308, 430–440.

- Foot 2011, pp. 138, 146–148; Pratt 2010, pp. 336, 350; Keynes 1999, p. 471; Brooks 1984, p. 218.

- Foot 2011, pp. 136–140, 146–147.

- Foot 2011, pp. 140–142.

- Pratt 2010, pp. 339–347; Foot 2011, pp. 143–145.

- Wormald 1999, pp. 300, 308.

- Pratt 2010, p. 349.

- Campbell 2000, pp. 32–33, 181; Foot 2011, p. 152.

- Foot 2011, pp. 151–155.

- Foot 2011, pp. 155–156.

- Foot 2011, pp. 95–96.

- Foot 2011, p. 97.

- Lapidge 2004; Yorke 2004.

- Wood 2010, pp. 148–149.

- Foot 2011, pp. 97–98, 215.

- Cubitt & Costambeys 2004.

- Brooke 2001, p. 115.

- Nelson 1999b, p. 112.

- Foot 2011, pp. 117–124; Keynes 1985, p. 180.

- Karkov 2004, p. 55.

- Blair 2005, p. 348.

- Foot 2011, pp. 135–136.

- Foot 2011, pp. 101–102.

- Blair 2005, p. 348; Dumville 1992, p. 156.

- Foot 2011, pp. 94, 99–107, 190–191; Keynes 1985, pp. 197–98; Brett 1991, pp. 44–45.

- Foot 2011, pp. 109–117.

- Lapidge 1993, p. 107; Gretsch 1999, pp. 332–334, 336.

- Keynes 1999, p. 470.

- Gretsch 1999, pp. 348–49.

- Foot 2011, pp. 72, 214–215.

- Foot 2011, p. 214, quoting an unpublished lecture by Stevenson.

- Lapidge 1993, p. 140.

- Woodman 2013, p. 247.

- Foot 2011, pp. 212–213; Ortenberg 2010, p. 215.

- Woolf 2007, p. 158.

- Keynes 2001, p. 61.

- Molyneaux 2015, p. 211.

- Ortenberg 2010, pp. 211–215; Foot 2011, p. 46.

- Karkov 2004, pp. 66–67.

- Foot 2011, pp. xv, 44–45.

- Sharp 1997, p. 198.

- Ortenberg 2010, pp. 217–218; Sharp 2001, p. 82.

- Foot 2011, pp. 46–49, 192–193; Ortenberg 2010, pp. 218–219.

- Foot 2011, pp. xvi, 48–52; Ortenberg 2010, pp. 231–232; Nelson 1999b, p. 112; Wormald 2004.

- Foot 2011, pp. 22–23, 52–53, 167–168, 167–169, 183–184.

- Zacher 2011, p. 84.

- Zacher 2011, p. 82.

- MacLean 2013, pp. 359–361.

- Stenton 1971, p. 344.

- Ortenberg 2010, p. 211; Foot 2011, p. 210.

- Wood 1983, p. 250.

- Ortenberg 2010, pp. 211–222.

- Beaven 1918, p. 1, n. 2.

- Foot 2011, pp. 25, 186–187, 243, plate 16 and accompanying text; Thacker 2001, pp. 254–255.

- Keynes 1999, pp. 472–473.

- Cooper 2013, p. 189.

- Dumville 1992, pp. 146, 167–168.

- Foot 2011, pp. 251–258, discussing an unpublished essay by Michael Wood.

- Dumville 1992, pp. 142–143.

- Miller 2014, p. 18.

- Foot 2011, pp. 71–73, 82–89, 98.

- Keynes 1999, pp. 465–467.

- Foot 2011, p. 247.

- Williams 1991b, p. 50.

- Lapidge 1993, p. 49.

- Stenton 1971, p. 356; Keynes 1999, p. 466.

- Dumville 1992, p. 171.

- Wood 2005, p. 7; Wood 2007, p. 192.

- Dumville 1992, chapter IV; Foot 2011.

- Keynes 2008, p. 25.

- Insley 2013, p. 323.

- Molyneaux 2015, p. 200.

- Foot 2011, pp. 10, 70.

- Dumville 1992, p. 167.

- Foot 2011, pp. 94, 211, 228.

- Roach 2016, pp. 95–96.

- Foot 2011, pp. 227–233.

- Foot 2011, pp. 233–42.

- Williams 1991b, p. 51.

Sources

- Abels, Richard (1998). Alfred the Great: War, Kingship and Culture in Anglo-Saxon England. Harlow, Essex: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-04047-2.

- Beaven, Murray (1918). "King Edmund I and the Danes of York". English Historical Review. 33 (129): 1–9. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXXIII.CXXIX.1. ISSN 0013-8266.

- Blair, John (2005). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921117-3.

- Blunt, Christopher (1974). "The Coinage of Æthelstan, King of England 924–939". British Numismatic Journal. XLII: 35–160 and plates. ISSN 0143-8956.

- Brett, Caroline (1991). "A Breton pilgrim in England in the reign of King Æthelstan". In Jondorf, Gillian; Dumville, D.N. (eds.). France and the British Isles in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-487-9.

- Brooke, Christopher (2001). The Saxon and Norman Kings. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-23131-8.

- Brooks, Nicholas (1984). The Early History of the Church of Canterbury. Leicester, UK: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7185-1182-1.

- Campbell, James (2000). The Anglo-Saxon State. London, UK: Hambledon & London. ISBN 978-1-85285-176-7.

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013). Wales and the Britons 350–1064. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Cooper, Tracy-Anne (March 2013). "Review of Æthelstan: The First King of England by Sarah Foot". Journal of World History. 24 (1): 189–192. doi:10.1353/jwh.2013.0025. ISSN 1045-6007. S2CID 162023751.

- Costambeys, Marios (2004). "Æthelflæd [Ethelfleda] (d. 918), ruler of the Mercians". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8907. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Cubitt, Catherine; Costambeys, Marios (2004). "Oda [St Oda, Odo] (d. 958), archbishop of Canterbury". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20541. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Davies, John Reuben (2013). "Wales and West Britain". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland c. 500–c. 1100. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-42513-8.

- Dumville, David (1992). Wessex and England from Alfred to Edgar. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-308-7.

- Foot, Sarah (2008). "Where English Becomes British: Rethinking Contexts for Brunanburh". In Barrow, Julia; Wareham, Andrew (eds.). Myth, Rulership, Church and Charters. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Ashgate. pp. 127–144. ISBN 978-0-7546-5120-8.

- Foot, Sarah (2011). Æthelstan: The First King of England. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12535-1.

- Foot, Sarah (2011a). "Æthelstan (Athelstan) (893/4–939), king of England". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/833.(subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Gretsch, Mechtild (1999). The Intellectual Foundations of the English Benedictine Reform. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03052-6.

- Hart, Cyril (1992). The Danelaw. London, UK: The Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-1-85285-044-9.

- Hart, Cyril (2004). "Sihtric Cáech (Sigtryggr Cáech) (d. 927), king of York". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49273. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Higham, N. J. (1993). The Kingdom of Northumbria: AD 350–1100. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Alan Sutton. ISBN 978-0-86299-730-4.

- Hill, Paul (2004). The Age of Athelstan: Britain's Forgotten History. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-2566-5.

- Hunter Blair, Peter (2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83085-0.

- Insley, Charles (2013). "Southumbria". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland c. 500–c. 1100. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-42513-8.

- John, Eric (1982). "The Age of Edgar". In Campbell, James (ed.). The Anglo-Saxons. London, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-014395-9.

- Karkov, Catherine (2004). The Ruler Portraits of Anglo-Saxon England. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell. ISBN 978-1-84383-059-7.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael, eds. (1983). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred & Other Contemporary Sources. London, UK: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044409-4.

- Keynes, Simon (1985). "King Æthelstan's books". In Lapidge, Michael; Gneuss, Helmut (eds.). Learning and Literature in Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 143–201. ISBN 978-0-521-25902-6.

- Keynes, Simon (1999). "England, c. 900–1016". In Reuter, Timothy (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. III. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 456–484. ISBN 978-0-521-36447-8.

- Keynes, Simon (2001). "Edward, King of the Anglo-Saxons". In Higham, N. J.; Hill, D. H. (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 40–66. ISBN 978-0-415-21497-1.

- Keynes, Simon (2008). "Edgar rex admirabilis". In Scragg, Donald (ed.). Edgar King of the English: New Interpretations. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. pp. 3–58. ISBN 978-1-84383-399-4.

- Keynes, Simon (2014) [1st edition 1999]. "Appendix I: Rulers of the English, c. 450–1066". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (Second ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 521–538. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Lapidge, Michael (1993). Anglo-Latin Literature 900–1066. London, UK: The Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-1-85285-012-8.

- Lapidge, Michael (2004). "Dunstan [St Dunstan] (d. 988), archbishop of Canterbury". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8288. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Livingston, Michael (2011). "The Roads to Brunanburh". In Livingston, Michael (ed.). The Battle of Brunanburh: A Casebook. Exeter, Devon: University of Exeter Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-85989-862-1.

- MacLean, Simon (2013). "Britain, Ireland and Europe, c. 900–c. 1100". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland c. 500–c. 1100. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-42513-8.

- Maddicott, John (2010). The Origins of the English Parliament, 924–1327. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958550-2.

- Miller, Sean (2014). "Æthelstan". In Michael Lapidge; John Blair; Simon Keynes; Donald Scragg (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Miller, Sean (2004). "Edward [called Edward the Elder] (870s?–924), king of the Anglo-Saxons". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8514. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Molyneaux, George (2015). The Formation of the English Kingdom in the Tenth Century. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871791-1.

- Nelson, Janet (1999a). Rulers and Ruling Families in Early Medieval Europe. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-86078-802-7.

- Nelson, Janet L. (1999b). "Rulers and government". In Reuter, Timothy (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume III c. 900–c. 1024. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–129. ISBN 0-521-36447-7.

- Nelson, Janet (2008). "The First Use of the Second Anglo-Saxon Ordo". In Barrow, Julia; Wareham, Andrew (eds.). Myth, Rulership, Church and Charters. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-5120-8.

- Ortenberg, Veronica (2010). "'The King from Overseas: Why did Æthelstan Matter in Tenth-Century Continental Affairs?'". In Rollason, David; Leyser, Conrad; Williams, Hannah (eds.). England and the Continent in the Tenth Century: Studies in Honour of Wilhelm Levison (1876–1947). Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-53208-0.

- Parker Library (8 September 2015). "History by the Month: September and the Coronation of Æthelstan". Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- Pratt, David (2010). "Written Law and the Communication of Authority in Tenth-Century England". In Rollason, David; Leyser, Conrad; Williams, Hannah (eds.). England and the Continent in the Tenth Century: Studies in Honour of Wilhelm Levison (1876–1947). Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-53208-0.

- Roach, Levi (August 2013). "Law codes and legal norms in later Anglo-Saxon England". Historical Research. Institute of Historical Research. 86 (233): 465–486. doi:10.1111/1468-2281.12001.

- Roach, Levi (2016). Æthelred the Unready. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22972-1.

- Ryan, Martin J. (2013). "Conquest, Reform and the Making of England". In Higham, Nicholas J.; Ryan, Martin J. (eds.). The Anglo-Saxon World. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 284–334. ISBN 978-0-300-12534-4.

- Scragg, Donald (2014). "Battle of Brunanburh". In Michael Lapidge; John Blair; Simon Keynes; Donald Scragg (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Sharp, Sheila (Autumn 1997). "England, Europe and the Celtic World: King Athelstan's Foreign Policy". Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester. 79 (3): 197–219. doi:10.7227/BJRL.79.3.15. ISSN 2054-9318.

- Sharp, Sheila (2001). "The West Saxon Tradition of Dynastic Marriage". In Higham, N. J.; Hill, D. H. (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21497-1.

- Smyth, Alfred P. (1979). Scandinavian York and Dublin. Vol. 2. Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: Humanities Press. ISBN 978-0-391-01049-9.

- Smyth, Alfred (1984). Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000. London, UK: Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-0-7131-6305-6.

- Stafford, Pauline (2014). "Ealdorman". In Michael Lapidge; John Blair; Simon Keynes; Donald Scragg (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Stenton, Frank (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Thacker, Alan (2001). "Dynastic Monasteries and Family Cults". In N. J. Higham; D. H. Hill (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21497-1.

- Williams, Ann (1991a). "Ælfflæd queen d. after 920". In Williams, Ann; Smyth, Alfred P.; Kirby, D. P. (eds.). A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain. London, UK: Seaby. p. 6. ISBN 1-85264-047-2.

- Williams, Ann (1991b). "Athelstan, king of Wessex 924–39". In Ann Williams; Alfred P. Smyth; D. P. Kirby (eds.). A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain. London, UK: Seaby. pp. 50–51. ISBN 1-85264-047-2.

- Williams, Ann (1991c). "Ealdred of Bamburgh". In Ann Williams; Alfred P. Smyth; D. P. Kirby (eds.). A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain. London, UK: Seaby. pp. 116–117. ISBN 1-85264-047-2.

- Wood, Michael (1983). "The Making of King Aethelstan's Empire: An English Charlemagne?". In Wormald, Patrick; Bullough, Donald; Collins, Roger (eds.). Ideal and Reality in Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. pp. 250–272. ISBN 978-0-631-12661-4.

- Wood, Michael (1999). In Search of England. London, UK: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-024733-6.

- Wood, Michael (2005). In Search of the Dark Ages. London, UK: BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-53431-0.

- Wood, Michael (2007). "'Stand strong against the monsters': kingship and learning in the empire of king Æthelstan". In Wormald, Patrick; Nelson, Janet (eds.). Lay Intellectuals in the Carolingian World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83453-7.