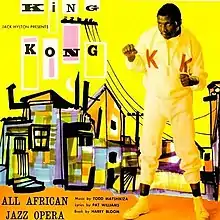

King Kong (1959 musical)

King Kong (1959) was a landmark[1] South African jazz-influenced musical, billed at the time as an "all-African jazz opera".

| King Kong | |

|---|---|

Original African Cast Recording | |

| Music | Todd Matshikiza |

| Lyrics | Todd Matshikiza Pat Willams |

| Book | Harry Bloom |

| Basis | the life of Ezekiel Dlamini |

| Premiere | 2 February 1959: Witwatersrand University Great Hallmaver |

| Productions | 1959 Johannesburg 1961 West End |

It has been called "an extraordinary musical collaboration that took place in apartheid-torn South Africa.... a model of fruitful co-operation between black and white South Africans in the international entertainment field, and a direct challenge to apartheid."[2] Opening in Johannesburg on 2 February 1959 at Witwatersrand University Great Hall, the musical, based on the life of Ezekiel Dhlamini[3] was an immediate success, with The Star newspaper calling it "the greatest thrill in 20 years of South African theatre-going".[4]

It "swept South Africa like a storm" according to one report,[5] touring the country for two years and playing to record-breaking multi-racial audiences, before being booked for a London production in 1961,[6] by which time it had been seen by some 200,000 South Africans.[4]

Background

The music and some of the lyrics for King Kong were written by Todd Matshikiza. The lyrics were by Pat Willams and the book by Harry Bloom.[7] The musical was directed by Leon Gluckman with orchestration and arrangements by pianist Sol Klaaste, tenor saxophonist Mackay Davashe, alto saxophonist Kippie Moeketsi and composer Stanley Glasser. King Kong was choreographed by Arnold Dover.

The decor and costumes were designed by Arthur Goldreich, a Jewish communist architect and visual designer (who was later arrested during an apartheid clampdown).

King Kong had an all-black cast. The musical portrayed the life and times of a heavyweight boxer, Ezekiel Dlamini, known as "King Kong". Born in 1921, his life degenerated, after a meteoric boxing rise, into drunkenness and gang violence. He knifed his girlfriend, asked for the death sentence during his trial and instead was sentenced to 14 years' hard labour. He was found drowned in 1957 and it was believed his death was suicide. He was 36.

After being a hit in South Africa, touring for two years during which it was seen by more than a quarter of a million people, of whom two-thirds were white, the musical played at the Prince's Theatre in the West End of London in 1961. The liner notes for the London cast recording state: "No theatrical venture in South Africa has had the sensational success of King Kong. This musical, capturing the life, colour, and effervescence -- as well as the poignancy and sadness -- of township life, has come as a revelation to many South Africans that art does not recognize racial barriers. King Kong has played to capacity houses in every major city in the Union [of South Africa], and now, the first export of indigenous South African theatre, it will reveal to the rest of the world the peculiar flavour of township life, as well as the hitherto unrecognized talents of its people. The show, as recorded here, opened at the Princes Theatre, London, on February 23, 1961."

The song "Sad Times, Bad Times" was considered a reference at the time to the infamous South African Treason Trial in Pretoria, which had begun in 1956 and lasted for more than four years before it collapsed with all the accused acquitted. Among the defendants were Albert Luthuli (African National Congress president), secretary Walter Sisulu, Oliver Tambo and Nelson Mandela. According to John Matshikiza, King Kong's first night was attended by Mandela, who at the interval congratulated Todd Matshikiza "on weaving a subtle message of support for the Treason Trial leaders into the opening anthem".[8] As Lewis Nkosi wrote: "The resounding welcome accorded to the musical at Wits University Great Hall, in Johannesburg, on Feb 2nd 1959, was not so much for the jazz musical as a finished artistic product as it was applause for an idea which had been achieved by pooling together resources from both black and white artists in the face of impossible odds."[2]

Cast

King Kong launched the international career of Miriam Makeba, who played the shebeen queen of the Back of the Moon, a popular shebeen of the time in Sophiatown.

The male lead was Nathan Mdledle of the Manhattan Brothers. There was a cast of 72, among them Caiphus Semenya, Sophie Mgcina, Letta Mbulu, Benjamin Masinga and Dottie Tiyo[9]

Other musicians in the show included Hugh Masekela,[10] Jonas Gwangwa, Kippie Moeketsi, Miriam Makeba,[11] Thandi Klaasen, all of whom went on to have successful careers. In the 2017 memoir King Kong – Our Knot of Time and Music by lyricist Williams, Abdullah Ibrahim – formerly known as Dollar Brand – puts the record straight about his supposed involvement with the musical: "In spite of what everyone says, I had nothing to do with it."[12] The London cast featured Nathan Mdlele and Peggy Phango, with Joseph Mogotsi, Ben Masinga, Stephen Moloi, Sophie Mgcina, Patience Gowabe and former "Miss South Africa 1955" Hazel Futa.

Peggy, Patience and Hazel later became The Velvettes, the backing vocal singers for Cyril Davies All Stars band and performed backing vocals on the Joe Meek-produced single "She's Fallen in Love with the Monster Man" by Screaming Lord Sutch and the Savages in 1964.

Songs

Original production:[13]

- "Sad Times, Bad Times"

- "Marvellous Muscles"

- "King Kong"

- "Kwela long"

- "Back of the Moon"

- "Petal’s Song"

- "Damn Him"

- "Strange"

- "Better than New"

- "Mad"

- "Quickly in Love"

- "In the Queue"

- "It’s a Wedding"

- "Death Song"

London production, 1961[14][15]

- Act I

- "Sad Times, Bad Times"—Overture (The Company)

- "Marvelous Muscles" (Nathan Mdlele and The Company)

- "King Kong" (Nathan Mdlele and The Company)

- "Kwela Kong" (Orchestra)

- "Back of the Moon" (Peggy Phango, Joseph Mogotsi)

- "The Earth Turns Over" (Sophie Mgcina and Men)

- "Gumboot Dance" (The Company)

- "Damn Him!" (The Company)

- "Party Tonight"

- "King King" (The Company)

- Act II

- "Be Smart, Be Wise" (Ben Masinga, Sophie Mgcina, Lemmy "Special" Mabaso, and Men)

- "Crazy Kid" (Lemmy "Special" Mabaso and The Alexander Junior Bright Boys)

- "Tshotsholosa -- Road Song" (The Company)

- "Quickly in Love" (Nathan Mdlele, Peggy Phango, Stephen Moloi, Ben Massinga, Patience Gowabe, Sophie Mgcina)

- "In the Queue" (The Company)

- "It's a Wedding" (The Company)

- "Wedding Hymn" (The Company)

- "Death Song" (Nathan Mdlele)

- "King Kong--Reprise" (The Company)

- "Sad Times, Bad Times--Finale" (Orchestra)

Plot

From the London cast recording liner notes (no indication of copyright):

In the dim light of early morning the township people set out for work ("Sad Times, Bad Times"). As Pauline, the washerwoman, leaves to deliver a bundle of washing a boy picks out a tune on a penny whistle—the "Little Kong" song, which has become a great favourite with the children. This sets the group reminiscing about the life of King Kong, who has become something of a legend in the township. And so we see the great King Kong in his heyday, surrounded by photographers, journalists and an excited township crowd ("Marvelous Muscles"). There is a big fight coming off, and everybody is confident it will be a pushover for the Champ ("King Kong"). King wins the fight and takes his friends to celebrate in Back of the Moon, the township's most famous shebeen ("Kwela Kong").

Joyce, who is the "shebeen queen", falls for King ("Back of the Moon"). Their love affair goes off at a hot pace, which is unlucky for Petal, who has a secret passion for the prizefighter ("The Earth Turns Over"). It is also bad news for Lucky, the fast and fancy leader of the Prowlers gang, who had previously been Joyce's man. Later, Lucky and his gang corner Popcorn, King Kong's friend and second, and King and his crowd arrive just in time to save him. In the ensuing brawl, King kills one of the gangsters with his fists, and Lucky swears to get even with him ("Damn Him!").

King spends ten months in the cells awaiting trial and Joyce finds new male company. King's trainer, Jack, signs up a new heavyweight, and continues with his pursuit of Nurse Miriam Ngidi. With King out of the picture, the Prowlers have it all their own way in the township. Then one Sunday when the streets are full of people ("Gumboot Dance") King Kong returns home acquitted. Everybody is overjoyed to see him and although King's pleasure sours a little when he learns about the new heavyweight, he is reassured by the tribal welcome home given him by the whole township ("King King").

Act Two opens with children playing in the township streets. Popcorn warns the children against boxing and tells of trouble in King Kong's camp ("Be Smart, Be Wise"). Lights go out, the township turns in for the night, then suddenly—crash! It is another snatch and grab raid by the Prowlers. Things are going badly for King. With Lucky and his gang exerting pressure on any prospective opponents, he can get no proper fights. The best Jack can do is to sign him up with Greb Mabisa, a middleweight. Lucky lets this fight go, knowing it will make a fool of King. Meanwhile, the ex-champ has laid off training, is making no attempt to get fit, and has fallen out with Joyce. But she agrees to give King one more chance, on condition that he never hits another man outside the ring. In the atmosphere of reconciliation, Jack at last announces that he and Nurse Miriam Ngidi are getting married ("Quickly in Love").

King loses the fight against Greb. The township is incredulous, and King experiences the scorn and mockery of the early morning bus queue the day after the fight ("In the Queue"). Lucky and his gang taunt him unmercifully. Enraged, he hits at the people in the queue, and Joyce, in disgust, walks out on him forever.

The whole town comes to Jack and Miriam's wedding ("Wedding Hymn") and in the middle of the ceremony King arrives, demanding "Where's Joyce?" A few minutes later Joyce comes in with Lucky, and in that moment King sees not only his own downfall, but Joyce's tragic return to the tough life of the shebeen keeper and gangster's girl. In blind fury, he kills Joyce. At his trial, a showman and eccentric to the end, King dismisses his lawyer, pleads guilty and asks the judge to sentence him to death ("Death Song"). He is given fifteen years imprisonment, but two weeks later drowns himself in a dam at the farm prison to which he was committed. As the show ends, it is evening in the township yard and the people are streaming back from work.

Legacy

In February 2017, saxophonist Soweto Kinch presented a BBC Radio 3 programme entitled King Kong – The Township Jazz Musical, with Hugh Masekela, Pat Williams and singer Abigail Kubeka among the featured guests.[2] A revival of the musical opened in autumn 2017 at the Fugard Theatre in Cape Town, produced by Eric Abraham, for whom it took 20 years to secure the rights.[9][16][17] It received positive reviews in South African press,[18][19][20] but drew unfavourable comparisons with the original production from a writer in Opera magazine.[21]

References

- John Blacking, "Trends in the Black Music of South Africa, 1959-1969", in Elizabeth May (ed.), Musics of Many Cultures: An Introduction, University of California Press, 1980, p. 197.

- "Sunday Feature: King Kong – The Township Jazz Musical" (Press release). London: BBC. Archived from the original on 4 May 2017.

- "King Kong the Musical 1959 -1961 | South African History Online".

- "King Kong, the first All African Jazz Opera", Soul Safari, 10 August 2009.

- Abbey Maine, "An African Theatre in South Africa", African Arts, Vol. 3, No. 4 (Summer, 1970), pp. 42–44.

- Percy Tucker biography at Just the Ticket.

- Todd Matshikiza, Harry Bloom, & Pat Williams, King Kong – The African Jazz Opera, London: Collins, 1961. OCLC 2399779.

- John Matshikiza, "An incomplete masterpiece" (5 February 1999), in Todd Matshikiza & John Matshikiza, With the Lid Off: South African Insights from Home and Abroad 1959-2000, Milpark: M&G Books, 2000; pp. 95–96.

- Marianne Thamm, "King Kong lives again: Iconic 1950s musical revival set to be highlight on SA 2017 cultural calendar", Daily Maverick, 10 January 2017.

- "Hugh Masekela – Musical Legend", January 2007.

- "South African Singer Miriam Makeba Dies". Billboard.

- Williams, P. (2017). King Kong - Our Knot of Time and Music: A personal memoir of South Africa's legendary musical. Granta Publications. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-84627-654-5.

- Original cast: King Kong – An African Jazz Opera, Gallo, catalogue no. CDZAC51R, 2003. (Via Stern's Music.)

- Muller, Carol Ann (2008). Focus: Music of South Africa. Focus on world music (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-415-96071-7. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- Jack Hylton Presents King Kong, All African Musical; London Production Cast, Original Cast Recording, Decca #LK 4392, 1961.

- "SA’s first ‘black’ musical King Kong returns with a world-class cast", City Press, 7 June 2017.

- "King Kong Cape Town", The Fugard Theatre.

- "BWW Review: Revival of KING KONG at The Fugard Theatre as Complex as it is Thrilling", Broadway World, 19 Aug 2017.

- "KING KONG REVIEW", WeekendSpecial, 6 Aug 2017.

- "ALL-BLACK SOUTH AFRICAN CAST EXPLOSIVE IN THE REWARDING "KING KONG" REVIVAL AT JOBURG MANDELA THEATRE", The Theatre Times, 11 Oct 2017.

- Ballantine, Christopher (2019). "Revisiting Todd Matshikiza's King Kong". South African Music Studies. 38 (1): 357–360. hdl:10520/EJC-1c9d39bfb0.

Further reading

- 1961 "Theater Abroad: Cry, the Beloved Country", Time magazine review, 3 March 1961.

- Pat Williams, King Kong – Our Knot of Time & Music: A personal memoir of South Africa’s legendary musical, Portobello Books, 2017, ISBN 978-1846276538.

- Various Press Clippings relating to the King Kong musical.