Sverre of Norway

Sverre Sigurdsson (Old Norse: Sverrir Sigurðarson) (c. 1145/1151 – 9 March 1202) was the king of Norway from 1184 to 1202.

| Sverre Sigurdsson | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Contemporary bust of Sverre from the Nidaros Cathedral, dated c. 1200.[1] | |

| King of Norway | |

| Reign | 1177 (claimed) /1184 (undisputed) – 9 March 1202 |

| Coronation | 29 June 1194, Bergen |

| Predecessor | Magnus V |

| Successor | Haakon III |

| Born | c. 1145/1151 |

| Died | 9 March 1202 Bergen, Kingdom of Norway |

| Burial | Old Cathedral, Bergen (destroyed in 1531) |

| Spouse | Margaret of Sweden |

| Issue | Christina of Norway Sigurd Lavard Haakon III of Norway |

| House | Sverre |

| Father | Unås Sigurd II of Norway (claimed; dubious) |

| Mother | Gunnhild |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism, excommunicated from AD1194, the King's dominions and Kingdom under Interdictum since AD1198, until his death, yet maintaining communion with the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (cf. Communion of the cults of Saint Olav and Saint Valdemar). |

Many consider him one of the most important rulers in Norwegian history. He assumed power as the leader of the rebel party known as the Birkebeiner in 1177, during their struggle against King Magnus Erlingsson. After Magnus fell at the Battle of Fimreite in 1184, Sverre ruled as sole king of Norway. Differences with the Church, however, led to his excommunication in 1194. Another civil war began against the church-supported Baglers, which lasted beyond Sverre's death in 1202.

The most important historical source on Sverre's life is his biography, the Sverris saga, in part written while Sverre was alive. This saga is likely biased, since the foreword states that part was written under Sverre's direct sponsorship. Correspondence between the pope and the Norwegian bishops can be used as an alternate source when it comes to church affairs. The saga and the letters mostly agree about the hard facts.

Supposedly, King Sverre was short, so he usually directed his troops from horseback during battles. The contrast is great to the traditional Norse warrior ideals where the king was expected to lead his men from the front of the battle line. Sverre was a talented improviser, both in political and military life. His innovative tactics often helped the Birkebeiners against more tradition-bound opponents. During battle he had his men operate in smaller groups, while previously tactics similar to the shield wall had been preferred. This made the Birkebeiners more mobile and adaptable.

Early life

According to the saga, Sverre was born in 1151 to Gunnhild and her husband Unås, a comb maker from the Faroes. When Sverre was five, the family moved to the Faroes where Sverre was raised in the household of Unås' brother Roe, bishop of the Faroes on Kirkjubøargarður in Kirkjubøur. It was here that Sverre studied for the priesthood and was ordained. The priest school of Kirkjubøur must have been of a high standard, for Sverre was later described as very well educated.[2] The legend says that he was hidden in a cave near the village. This cave actually exists and gave the mountain Sverrihola (303 m, "Sverre's cave") on the south tip of Streymoy its name.

Sverre, however, was not suited for a priestly life. The saga states that he had several dreams which he interpreted as a sign that he was destined for greater things. Further, in 1175, his mother revealed that Sverre was really the son of King Sigurd Munn. In the following year, Sverre travelled to Norway to seek his destiny.

Paternity

The tale told in Sverre's saga is the official version. Historians have questioned the veracity of it, especially with regard to Sverre's alleged paternity.[3] Some historians have considered his claim to be King Sigurd's son to be false, as did many of his contemporaries. Others have believed the paternal claim to be true, while most historians have found that the paternal question cannot be given a definite answer.[3] Although the fact that kings fathered illegitimate sons was taken for granted, other facts indicate that Sverre was in his early thirties when he came to Norway, such as the age of his own sons and nephews. It has been cited against Sverre's claim that according to Canon law, one had to be at least 30 years old to be eligible for the priesthood. If Sverre was 30 years old when he became a priest, this would place his birth no later than 1145, making his paternal claim impossible, as Sigurd Munn was born in 1133. This particular objection has lost credence as it has become clear that this age limit was routinely ignored in Scandinavia at the time. However, other objections remain, such as the fact that Sverre consistently refused to undergo an ordeal by fire to prove his claims. At the time, such a trial was routine for new claimants to the throne, and belief in its efficacy seems to have been universal; yet Sverre refused to undergo it. If Sverre's claim was false, however, he would lack royal legitimacy, dooming his plans to failure. Regardless, his motivation is clear: to capture the throne of Norway, whether he could prove royal blood or not. After all, Norway had seen other claimants, since Harald Gille, whose paternity was equally questionable.

The fact that Sigurd Munn's daughter Cecilia acknowledged Sverre as the son of Sigurd is inconclusive. Sverre's actions offered her a welcome possibility to divorce from the marriage with Folkvid the Lawspeaker, into which she claimed to have been forced by Erling Skakke.

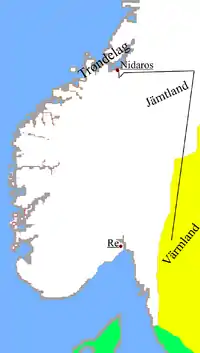

Support from Earl Birger Brosa of Sweden is more a sign of pragmatic politics on the part of the Swedes, as their ally party in Norway needed a new leader and had chosen Sverre. Sverre was not the Earl's first choice, however. They had first supported Øystein Møyla, who had died at the Battle of Re in 1177. The Swedish dynastic lines were themselves engaged in civil war, and the current rulers of the family after King Erik were at war with the Danish king Valdemar. Erling Skakke had submitted to Valdemar some decades earlier, and it was beneficial for the Swedes at the time to support the opponents of Erling's regime, namely Sverre.

Norway in 1176

In 1176, Norway was slowly recovering from decades of multiple civil wars. The causes were largely due to the lack of any clear succession laws. According to the old customs, all the king's sons, legitimate or illegitimate, had equal right to the throne. It was customary for brothers to rule the kingdom together, but when quarrels arose, war was frequently the result.

Sigurd Munn, claimed by Sverre as his father, had been slain by his brother Inge Krokrygg in 1155. Sigurd's son Håkon Herdebrei had been chosen to be king by his father's followers. The conflict was now a regional conflict, with King Inge having the strongest support in Viken, while most of Håkon's followers were from Trøndelag. Inge Krokrygg fell in 1161. His party then took the five-year-old Magnus Erlingsson as king. Magnus was the son of Erling Skakke and Kristin, daughter of King Sigurd the Crusader. In 1162, at the Battle of Veøy, Håkon Herdebrei fell and his faction began to fall apart. In 1164 Magnus was crowned by Archbishop Øystein Erlendsson. With the Church and most of the aristocracy on his side, Magnus' kingship seemed secure. Several uprisings followed, but they were all suppressed. Erling Skakke had been regent during his son's minority and continued to be the country's real ruler even after Magnus had come of age.

Sverre meets the Birkebeiners

Thus when Sverre came to Norway he found the prospects for a successful uprising to be small. Distraught, he travelled east and came to Östergötland in Sweden just before Christmas. There he met with the local ruler, Birger Brosa, who was married to Sigurd Munn's sister, Brigit Haraldsdotter. Sverre revealed to Birger Brosa his claim to the throne, but Birger was at first unwilling to give any aid. He was already supporting another group, the Birkebeiners — the Birchlegs. This group had risen in 1174 under the leadership of Øystein Møyla who claimed to be the son of King Øystein Haraldsson. They had received the name Birkebeiners because their poverty led some of them to wind the bark of the birch about their legs, instead of wearing shoes. But in January 1177, the Birkebeiners met a crushing defeat at the Battle of Re and Øystein fell. Sverre met with the remnants in Värmland. After some initial doubts, Sverre let himself be persuaded to become the Birkebeiners’ next leader.

Rise to power

Upon Sverre's initial contact, the Birkebeiners had been reduced to a ragtag army of brigands and vagabonds with no more than 70 men, according to the saga. Many regard Sverre's achievement of forging them into a force of skilled and professional soldiers as proof of his leadership qualities.

Difficult years

During the early years as leader of the Birkebeiners, Sverre and his men were almost constantly on the move. The Birkebeiners were generally viewed as troublemakers with little chance of success by the general populace, who most of all desired peace. Although peasant gatherings were no match for the battle hardened Birkebeiners, Magnus or Erling Skakke frequently had the Birkebeiner on the run.

In June 1177, Sverre first led his men to Trøndelag where Sverre was proclaimed as king at Øretinget. Since this was the traditional place to choose a king, the event carried important symbolic weight. The Birkebeiners then moved south to Hadeland, where they were forced northwards again. Sverre then decided to turn west, attempting to take Bergen by surprise. At Voss, however, the Birkebeiners were ambushed by the local peasants. Although the Birkebeiners were victorious, the surprise element on Bergen was eliminated, forcing the group eastwards again. After almost freezing to death on Sognefjell, they wintered in Østerdal.

The next spring, after a short stay in Viken, Sverre and the Birkebeiners returned to Trøndelag. The Birkebeiners now shifted to a more confrontational strategy. However, an attack on Nidaros ended in defeat at the Battle of Hatthammeren (Slaget på Hatthammeren). After fleeing south, they met Magnus' army in Ringerike, with the skirmish ending in a tactical victory for the Birkebeiners. Encouraged, the Birkebeiners returned to Trøndelag and managed to subdue the region enough to stay in Nidaros during the winter.

In the spring of 1179, Magnus and Erling Skakke attacked Nidaros, forcing another apparent retreat. Confident that the Birkebeiners had again fled southwards, Magnus and his men were complacent. Sverre, however, had turned around at Gauldal and marched again upon the city. The two armies met 19 June in the Battle of Kalvskinnet. Erling Skakke was killed in a battle that ended in a clear victory for Sverre. This victory secured Sverre's hold on Trøndelag.

Victory over the Heklungs

After Sverre's victory at Kalvskinnet, the war changed somewhat in character. The Trønders accepted Sverre as their king; the two sides were now much more equal in power. At some point, Magnus' party acquired the nickname Heklungs (Heklunger). Hekle is Old Norse for hood and is here probably meant to imply the traditional monk garb.

Several battles now followed. Magnus Erlingsson again attacked Trøndelag in the spring of 1180, this time reinforced by conscripts from western Norway. But in the Battle of Ilevollene (Slaget på Ilevollene), just outside Nidaros, the Heklungs were again defeated and Magnus fled to Denmark. With Magnus out of the country, Sverre could sail south and occupy Bergen, but his hold on the region remained weak.

Determined to achieve a decisive victory against the Birkebeiners, Magnus returned with his fleet the next year. The two forces met at sea 31 May 1181 in the Battle of Nordnes. The battle ended in a tactical victory for the Birkebeiners; the Heklungs fled when Magnus was mistakenly believed to have been killed. With his men in poor shape, Sverre decided to withdraw to Trøndelag. Some attempts at negotiation were now made, but these soon broke down. Magnus would not accept Sverre as co-king with equal status, and Sverre could not accept becoming Magnus' vassal.[4]

With Magnus controlling western Norway from his seat at Bergen, it became problematic for Sverre to keep his men supplied. Sverre therefore led his men south to Viken, a firm Heklung stronghold. He could therefore let his men plunder here with little damage to his cause. However, Magnus exploited Sverre's absence well.[5] In November he raided Trøndelag and managed to seize and burn the Birkebeiner fleet. Sverre had to return or risk losing his one secure foothold.

During summer 1182, Magnus made an attempt to take Nidaros by siege, but was repulsed with grave losses when the Birkebeiners launched a surprise night attack. Sverre now started an extensive shipbuilding program. Without a fleet, he could have no hopes of expanding his influence further south. In spring 1183 Sverre attacked Bergen with parts of his new fleet. Avoiding detection by the enemy scouts, he caught the Heklungs off guard, seizing their entire fleet. Magnus fled to Denmark, leaving crown and sceptre behind.

In the sea battles of medieval Scandinavia, the side with the largest and highest ships would usually have an advantage, since this meant the crew could attack the enemy from above with projectiles and other weapons. Sverre built the largest ship afloat at the time, the Mariasuda. Because of its great size, the seaworthiness of the Mariasuda was rather poor and it would only be useful within the narrow fjords. Either because of luck or good strategy such a situation would soon arise.

Early spring 1184, Magnus returned to Viken from Denmark with new ships. In April he sailed north towards Bergen. At about the same time, Sverre had gone to Sogn to put down a local uprising and was still there when Magnus came to Bergen in June. After chasing out the few Birkebeiners there, Magnus set sail again, having heard news of Sverre's current position. The two fleets met 15 June at Fimreite in the long and narrow Sognefjord. The Battle of Fimreite proved to be the final struggle between Birkebeiners and Heklungs. Magnus had several large ships, but none as huge as the Mariasuda. While the Mariasuda held up half of the enemy fleet, the rest attacked the outlying enemy ships. Panic began to spread as the Heklungs fled aboard their larger ships. These ships soon became overloaded and began to sink. Many of the wounded and tired men could not keep themselves afloat and drowned, including King Magnus. Most of the Heklung leadership fell there, along with a huge number of men at both sides.[6] Leaderless, the Heklungs were now broken as a political party. Sverre could now finally, after a six-year struggle, claim to be the sole and uncontested king of Norway.

Troubled reign

Now that the dissatisfied priest and his band of vagrants and outcasts had become king and rulers of Norway, Sverre worked to consolidate his power. He placed his loyal men in high positions (sysselmann) throughout the kingdom and negotiated marriage alliances between the old and new nobility. Sverre himself married the Swedish princess Margaret, daughter of Erik the Saint and sister of King Knut Eriksson of Sweden.

Although Norway had seen several conflicts in the previous decades, the victor had reconciled with his opponents. Reconciliation in Sverre's case, however, proved to be difficult. It was a long war with more casualties than previous conflicts. Most of the older noble dynasties had lost men and thirsted for vengeance. Further, that many people of non-noble origin were now elevated to noble standing was difficult for many to accept. Peace was not to last long.

Kuvlungs and Øyskjeggene

Autumn 1185 the Kuvlungs (Kuvlungene) rose in Viken. Their leader, Jon Kuvlung, was a former monk and was claimed to be the son of Inge the Hunchback. This group was in many ways the direct successor of the Heklungs, with many of its members coming from former Heklung families. The Kuvlungs soon gained control of eastern and western Norway, the old Heklung strongholds.

In autumn 1186, the Kuvlungs attacked Nidaros. This offensive took Sverre by surprise; he took refuge in the recently constructed stone castle Sion. The Kuvlungs, unable to take the castle, were forced to retreat. In 1188 Sverre sailed south with a large fleet. They first met at Tønsberg, but neither side dared to offer battle. The Kuvlungs slipped away to Bergen. Sverre attacked Bergen just before Christmas. Jon Kuvlung was killed, which ended the Kuvlung rising. Some minor uprisings followed, but these never rose above banditry and were suppressed on a local scale.

The next serious threat came in 1193 with the Øyskjeggene (the Isle Beards). This group's pretender to the throne was Sigurd, a child claimed to be the bastard son of Magnus Erlingsson. The real leader was Hallkjell Jonsson who was Magnus’ brother-in-law. Conspiring with the earl of Orkney, Harald Maddadsson, Hallkjell gathered most of his men on the Orkney and Shetland Islands, hence the name of the group. After establishing themselves in Viken, the Øyskjeggene sailed on to Bergen. Although they occupied the city itself and the surrounding regions, a force of Birkebeiners held on in Sverresborg castle. In spring 1194 Sverre sailed south to confront the Øyskjeggene. The two fleets met 3 April in the Battle of Florvåg (slaget ved Florvåg). Here the battle experience of the Birkebeiner veterans proved to be decisive. Hallkjell fell with most of his men.

Sverre and the church

.png.webp)

The Church of Norway had been organized under the Archbishopric of Nidaros in 1152. Øystein Erlendsson, who had become archbishop in 1161, had been one of Magnus Erlingsson's main supporters. In return, the church had secured its position as an independent institution and also gained several other privileges.

Øystein had returned to Nidaros from England in 1183, and during his last years a state of truce existed between church and king. When Øystein died on 26 January 1188, Eirik Ivarsson, bishop of Stavanger, was elected as his successor. Sverre now probably hoped that his relationship with the church could be normalised. He therefore approached Eirik with hopes of being crowned — the definite proof of recognition. However, in Eirik's eyes, Sverre was little more than a usurper and king-murderer.[7]

The situation now escalated into an open breach as Sverre began building up a list of privileges that were contrary to the church law made by St. Olaf, the traditional founder of the Norwegian Church. Eirik on his side preached against the king and his men, and sent letters of complaint to the Pope, but in the short term his offensive weapons were few. In 1190 Sverre attempted to force the archbishop into submission, claiming that Eirik had broken the law by having 90 armed men in his service. According to law, the archbishop's guard was limited to 30 men. Rather than submit to the king's will, Eirik fled to Lund where the Danish archbishop had his seat. From there he sent a delegation to Rome asking the pope for advice.[8]

With the archbishop absent, Sverre tightened his grip on the bishops, and on Nikolas Arnesson in particular. Nikolas was the half-brother of Inge Krokrygg and had become bishop of Oslo in 1190 against Sverre's wish. After the destruction of the Øyskjeggs at Florvåg, Sverre arranged a meeting with Nikolas where he claimed to have proof that the bishop had colluded with the Øyskjeggs. The king accused Nikolas of treason and threatened severe punishment. Nikolas submitted, and on 29 June, together with the other bishops, he crowned Sverre. Sverre's domestic priest was elected bishop of Bergen.

Meanwhile, archbishop Eirik had at last received a reply from Rome. In a letter dated 15 June 1194, Pope Celestine III laid out the foundational rights of the Norwegian Church supporting Eirik on every point.[9] Empowered by this letter, Eirik could take the step of excommunicating Sverre and order the Norwegian bishops to join him in exile in Denmark.

The following spring, Sverre sent the still loyal Tore, bishop of Hamar, to Rome to plead his case before the pope. He returned in early 1197, according to the saga, carrying a papal letter which annulled the excommunication of Sverre. In Denmark, Tore is said to have fallen ill and died under suspicious circumstances, but not before pawning the papal letter.[10] The pawnbrokers then travelled to Norway and delivered it to Sverre who used it for everything it was worth. No other sources confirm this story and most historians now agree that the letter was forged.[11]

With the death of Pope Celestine in January 1198, the conflict entered a short lull until the new pope, Innocent III, had brought himself up to date, but then the conflict was further escalated. In October, Innocent III placed Norway under interdict and in letters to Eirik accused Sverre of forgery.[12] He also sent letters to admonish neighboring kings to dispossess Sverre. They did the contrary: Sweden continued actively to support the Birkebeiners and John of England sent mercenaries to help Sverre. In 1200 Innocent found it necessary to warn the Archbishop of Canterbury not to accept further gifts from Sverre.[13]

Around this time someone close to Sverre wrote a speech against the bishops, En tale mot biskopene. In this work, the unknown author discussed the relationship between King and Church. By referring to well known theological works such as the Decretum Gratiani and the writings of Augustine of Hippo, the author attempted to prove that the excommunication of Sverre was unjust and thus not binding. The author also tried to defend the right of Sverre to appoint bishops. To support this view he had to interpret Norwegian law, since the Church had long considered this to be simony. By now Sverre had his hands full with the church-supported Bagler rising, and the direct struggle with the church became a sideshow, at least for him personally.

The Bagler war

During spring 1196 the Bagler party was formed at Halør in Denmark in opposition against Sverre. Their leaders were Nikolas Arnesson, the nobleman Reidar Sendemann from Viken and Sigurd Jarlsson, a bastard son of Erling Skakke. Eirik the Archbishop also gave his support. As their king, they chose Inge Magnusson, supposedly the son of Magnus Erlingsson. They then sailed back to Norway.

Sverre happened to be in Viken, and the two forces soon encountered each other, although no major battles were fought. Sverre gave his eldest son, Sigurd Lavard, the responsibility of guarding a ballista he had had built. However, the Baglers launched a surprise night attack during which the ballista was destroyed and Sigurd and his men were chased away. Sverre was furious and never gave his son a command again. After some more indecisive fighting, Sverre sailed north to Trondheim, where he spent the winter. The Baglers had Inge hailed as king on Borgarting and soon established a firm control over the Viken region, with Oslo as their main seat.

In spring 1197, Sverre called out the leidang from the northern and western parts of the country, and in May he was able to sail south to Viken with more than 7000 men, a considerable force. The Birkebeiners attacked Oslo 26 July, and after many casualties on both sides, the Baglers were forced inland. Sverre now spent some time war-taxing the region, but with his leidang troops close to mutiny, Sverre withdrew to Bergen where he had decided to spend the winter. This was to be a near fatal mistake. The Baglers had meanwhile travelled north to Trøndelag by land where they had entered Nidaros with little opposition. The garrison at Sverresborg held fast for a while until their commander Torstein Kugad changed sides and let the Baglers into the castle. The Baglers had Sverresborg completely dismantled. Sverre's home region was now in enemy hands.

The year 1198 was to be the nadir of Sverre's fortunes. In May Sverre launched his attempt to recapture Trøndelag. This time Sverre failed to achieve surprise and the Birkebeiner fleet consisted mostly of smaller ships. In the sea battle that followed, the Birkebeiners were soundly beaten. In the aftermath of this battle the Baglers further consolidated their hold on Trøndelag and many went over to what they believed to be the winning side.

After his defeat, Sverre limped back to Bergen. He was soon followed by a numerically superior Bagler army under the leadership of Nikolas Arnesson and Hallvard of Såstad. Sverre continued to hold Bergenhus fortress. This castle proved to be impregnable, giving the Birkebeiners a secure base of operation. The following summer was to be called the "Bergen’s summer" and was dominated by indecisive skirmishing in the Bergen area. On 11 August the Baglers set fire to Bergen. The destruction was complete, even the churches were burnt down. Facing starvation, Sverre slipped away with most of his men to Trøndelag.

In Trøndelag, most of the population was still loyal to Sverre, and many of those who had joined the Baglers now changed sides again. Sverre was also able to play on the Baglers' brutality at Bergen. The Trønders promised to provide Sverre with a new fleet, in all 8 large ships were constructed and several transport ships were converted. The Baglers sailed into the Trondheimsfjord in early June. On 18 June 1199 the two fleets met at the Battle of Strindafjord (slaget på Strindfjorden). Here Sverre won a crushing victory, and the surviving Baglers fled to Denmark.

Sverre could now take control over Viken and prepared to spend the winter in Oslo, but the countryside remained largely hostile. Early the next year, a spontaneous uprising took place as huge numbers of people started drifting towards Oslo to throw the Birkebeiners out. This peasant army was untrained and without organization and was no match for the battle-hardened Birkebeiners. In a battle on 6 March 1200 the peasants were defeated piecemeal. However, the Birkebeiners' grip on the region was still weak, and Sverre decided to sail back to Bergen.

With Sverre gone, the Baglers could return in force from Denmark and soon they had re-established their hold on Eastern Norway. The two sides then spent a year raiding each other's territories with no lasting gains for either side, although the Birkebeiners had the upper hand at sea.

In Spring 1201 Sverre sailed out from Bergen with a large leidang force in what would be his last campaign season. With this army he could demand war taxes without opposition on both sides of the Oslofjord during the summer. In September he set up camp at Tønsberg and laid siege to Tønsberg Fortress, which was garrisoned by Reidar Sendemann and his men. The siege dragged on because the other Bagler leaders dared not send a relief force and the garrison did not fall for any of Sverre's tricks. At last, on 25 January, Reidar and his men surrendered, and Sverre decided to sail back to Bergen.

During the return journey Sverre fell ill, and by the time they reached Bergen, the king was dying. On his death bed, Sverre appointed his sole living son, Håkon, as his heir and successor and in a letter advised him to seek reconciliation with the Church. Sverre died 9 March 1202. He was buried in Christ Church, Bergen, which was destroyed in 1591.

Notes

- Sverre Sigurdsson (Store norske leksikon)

- Debes, Hans Jacob (2000). "1". Hin lærdi skúlin í Havn (in Faroese). Sprotin. pp. 12–15. ISBN 99918-44-57-0.

- Knut Helle: Sverre Sigurdsson (in Norwegian) Norsk biografisk leksikon,

- Krag 2005:113–116

- Krag 2005:117

- The saga gives 2160 as the total number of dead for both side. The various numbers given in the saga are generally plausible, though some over estimation is likely.

- Krag 2005:151

- Diplomatarium Norvegicum vol. VI, page 4

- Diplomatarium Norvegicum vol. II, page 2

- Jonsson 1995:153

- Bagge 2005:164

- Diplomatarium Norvegicum vol. VI page 10

- Diplomatarium Norvegicum vol. XVII page 1221

References

- Karl Jonsson; et al. (1995) [1967]. Sverresoga. translation to Norwegian by Halvdan Koht (6th ed.). Oslo: Det Norske Samlaget. ISBN 82-521-4474-8.

- Claus Krag (2005). Sverre – Norges største middelalderkonge. Oslo: H. Aschehoug & Co. ISBN 82-03-23201-9.

- Sverre Sigurdsson – Nordisk familjebok

- Diplomatarium Norvegicum

- Geoffrey Malcolm Gathorne-Hardy (1956). A royal impostor: King Sverre of Norway. London: Oxford University Press.

External links

- Oslo's coin cabinet – coins issued by Sverre

- The Saga of King Sverri of Norway – a translation from 1899

- The Saga of King Sverri of Norway – a translation from 1899

- Of Sverre, King of Norway – from William of Newburgh's History of English Affairs, Book three, chapter six