Zhang Shicheng

Zhang Shicheng (simplified Chinese: 张士诚; traditional Chinese: 張士誠; pinyin: Zhāng Shìchéng; 1321-1367), born Zhang Jiusi (張九四), was one of the leaders of the Red Turban Rebellion in the late Yuan dynasty of China.

| Zhang Shicheng 張士誠 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Reign | 1354–1357 (King of Zhou) 1363–1367 (King of Wu) | ||||||||

| Born | Zhang Jiusi (張九四) 1321 Zhizhi 1 (至治元年) | ||||||||

| Died | 1367 (aged 45–46) Zhizheng 27 (至正二十七年) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Zhou → Wu | ||||||||

Early life

Zhang Shicheng came from a family of salt shippers, and he himself started out in this trade in Northern Jiangsu, transporting both "legal" and "contraband" salt, as did his brothers Zhang Shiyi (张士義), Zhang Shide (张士德), and Zhang Shixin (张士信). By his generosity he earned the respect of other salt workers who made him their leader when they rebelled against the oppressive government in 1353.[1][2]

Since the 1340s, the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty began to face numerous crises. The Yellow River flooded constantly, and other natural disasters also occurred. At the same time, the Yuan dynasty required considerable military expenditure to maintain its vast empire. This was solved mostly through additional taxation that fell mainly on the Han Chinese population which constituted the lowest two castes in the four castes of the Yuan dynasty. From this chaos, leaders rose up in many places throughout the empire. Zhang Shicheng, who was a salt shipper from Jiangsu province rebelled against the Yuan dynasty in 1353. Zhang with his brother soon conquered Taizhou, Xinghua and Gaoyou in 1353.

Regional rule

In 1354, Zhang declared the establishment of the Da Zhou state[3] and declared himself King Cheng (誠王) with the era name "Tianyou" (天佑). Soon afterward, on the same year Zhang controlled Yangzhou, an important center of salt trade on the Grand Canal of China, just north of the Yangtze.

In 1356, Zhang seized Suzhou,[4] the main hub of transportation and commerce of Jiangnan (the "South of the Lower Yangtze" region), and made the city his capital. The lands he now controlled not only were one of the country's main granaries, but also produced over half of all salt in China.[2] Zhang's regime was mostly patterned on the Yuan dynasty model, but made use of some of the earlier traditional Chinese terminology as well.[2]

_-_3_Cash_-_Scott_Semans.jpg.webp)

Zhang appointed his brother Zhang Shixin as prime minister and Zhang Shide as General commander. Many ethnic Han Yuan generals submitted to Zhang after he had established the Zhou state. The Zhou became the most prosperous kingdom compared to its rivals such as the Yuan, Zhu Yuanzhang and Chen Youliang.

The Yangtze Delta literati strongly backed the Zhou regime, and because of this, his rival the future Ming emperor Zhu Yuanzhang was highly suspicious of them. When the highly educated Southern literati came to dominate the civil service examinations, the emperor would set quotas and restrictions on their appointments to curb them.[5][6]

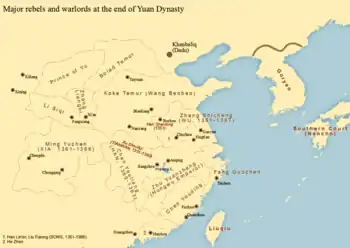

Around that time, his main rival for domination in central China became Zhu Yuanzhang, who had just installed himself in Nanjing. It is reported that after several defeats from troops loyal to Zhu in 1356–57, Zhang offered to pay tribute to Zhu in exchange for the recognition of his autonomy.[7] Zhu, however, refused Zhang's offer,[7] and in 1357, Zhang accepted a title from the Yuan government, and agreed to start shipping grain to the Yuan capital (Beijing) region by sea.[2]

Zhang had significantly expanded his domain by 1363, when he declared himself the King of Wu (吴王, Wu Wang), possibly following the example of his main rival, the Nanjing-based Zhu Yuanzhang, who had earlier (1361) made himself the Duke of Wu (吴公, Wu Gong). Not to be outdone, in 1364, Zhu promoted himself to a King (Wang) of Wu as well.[2][8]

Fall and legacy

It is speculated by modern historians that if Zhang had been more decisive and cooperated with another rival (and the western neighbor) of Zhu, Chen Youliang, Zhang and Chen could have crushed Zhu's incipient Ming state. However, "indolent" Zhang was apparently content to merely control the lower Yangtze region; his two attempts to attack Zhu's territories were both defeated decisively.[7]

After Zhu Yuanzhang's victory over Chen Youliang and his son Chen Li and taking full control of their former territories (by around 1365), Zhu was able to turn more of his fighting power against Zhang.[7] Zhu's started with cutting off Zhang from any possible aid from the Yuan rulers in the north. This was accomplished by his taking Gaoyou on the Grand Canal of China on April 24, 1366. In the same year (1366), Zhang lost his younger brother Zhang Shide, who was also an important general in his army, feared by Zhu's troops, when the younger Zhang fell from his horse and died.[9] By late December 1366, Zhang's capital Suzhou was surrounded by Zhu's army.[7]

The struggle between the two "Kings of Wu" came to the end on October 1, 1367, when Suzhou fell to Zhu Yuanzhang's troops after a 10-month siege.[7] Zhang tried to hang himself. but was discovered in the act, captured, and taken to Zhu's capital, Nanjing.[7] What happened to Zhang there is not known for sure: according to various sources, he was either beaten to death[2][8] or finally managed to hang himself successfully.[7][10] Meanwhile, Zhu incorporated a quarter million of Zhang's troops into his army,[7] proclaimed himself the first emperor of the new Ming dynasty on the (Chinese) New Year Day of 1368 (January 20 or 23, 1368) and punished Zhang's surviving supporters in Suzhou by extortionate taxes.[2][8]

Zhang Shicheng's tomb in Xietang, Suzhou is still standing today. After his death, his memory still made an impression in the hearts of the peoples of Suzhou. On every 30 July (Zhang's birthday), the locals of Suzhou celebrated with straw dragon toys hanging at the doors of their houses. At the same time, they set fire to 94 straw stems, the significance being "9" and "4" forming Zhang's birth name; at the same time, it was a homonym for "continued remembrance" (久思). According to tradition, as emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang became suspicious of these local practises, and asked local officials to investigate; the locals claimed that they were worshipping Kṣitigarbha (地藏王, Dizangwang in Mandarin). This was again another word play as the locals were actually worshipping Zhang as a local prince (地张王, Dizhangwang). This celebration continued under Communist rule, and lasted until the establishment of the People's Republic of China.

Luo Guanzhong and Zhang Shicheng

Although very little reliable information exists about the life of the famous novelist Luo Guanzhong, some scholars surmise that Luo may have been a member of Zhang Shicheng's staff during the early days of Zhang's kingdom. It is believed Luo became disillusioned with Zhang after he made accommodations with the Mongol rulers. After the disillusionment, Luo turned to a literary career, writing his Romance of the Three Kingdoms. However, the scant historical evidence has been interpreted in various ways, with arguments in favor of Luo having been on the side of other participants in the conflict.[11]

References

Citations

- Tora Yoshida, Hans Ulrich Vogel, Salt Production Techniques in Ancient China. On Google Books, p. 48

- Edward L. Farmer, Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. BRILL, 1995. ISBN 90-04-10391-0, ISBN 978-90-04-10391-7. On Google Books. P. 23.

- Needham, Joseph; Ling Wang Science and civilisation in China, Volume 4, Part 1 Cambridge University Press; 1 edition (8 May 2008) ISBN 978-0-521-87566-0 p. 292

- Hay, Jonathan. "ART OF THE MING DYNASTY (1368-1644)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-17. Retrieved 2023-08-24.

- Benjamin A. Elman (2013). Civil Examinations and Meritocracy in Late Imperial China. Harvard University Press. pp. 25–28. ISBN 978-0-674-72604-8.

- Benjamin A. Elman (2000). A Cultural History of Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China. University of California Press. pp. 90–92. ISBN 978-0-520-92147-4.

- Peter Allan Lorge (2005). War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900-1795: 900 - 1795. Taylor & Francis. pp. 101, 104–105. ISBN 978-0-415-31691-0.

- Linda Cooke Johnson, Cities of Jiangnan in Late Imperial China. SUNY Press, 1993. ISBN 0-7914-1423-X, 9780791414231 On Google Books, pp. 26-27.

- History of Ming (明代史),ed: Fu Lecheng (zh:傅樂成),Changqiao (長橋) Publishers, 1980

- Zhang Shicheng

- Luo Guanzhong; Kuan-Chung Lo; Moss Roberts (1999). Three Kingdoms: A Historical Novel. University of California Press. pp. 450–451. ISBN 978-0-520-21585-6.

External links

Media related to Zhang Shicheng at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Zhang Shicheng at Wikimedia Commons