Kings County Hospital Center

Kings County Hospital Center is a municipal hospital located in the East Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York City. It is owned and operated by NYC Health + Hospitals, a municipal agency that runs New York City's public hospitals. It has been affiliated with SUNY Downstate College of Medicine since Downstate's founding as Long Island College Hospital in 1860.[1] Kings County is a member of the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation.

| Kings County Hospital Center | |

|---|---|

| NYC Health + Hospitals | |

| |

Building S of the hospital in 2015 | |

| Geography | |

| Location | 451 Clarkson Avenue 11203, East Flatbush, Brooklyn, New York, United States |

| Coordinates | 40°39′24″N 73°56′42″W |

| Organization | |

| Funding | Public hospital |

| Type | Teaching |

| Affiliated university | SUNY Downstate College of Medicine[1] |

| Network | NYC Health + Hospitals[1] |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | Level I trauma center |

| Beds | 627[1] |

| History | |

| Opened | 1831[1] |

| Links | |

| Website | nychhc |

| Lists | Hospitals in New York |

| Other links | Hospitals in Brooklyn |

Kings County was named the country's first Level 1 trauma center.[2] It is also a Designated Stroke Center, Level III Perinatal Center, Designated AIDS Center, Parkinson's Disease Center of Excellence, Diabetes Education Center of Excellence, Behavioral Health Center (including inpatient, outpatient with dedicated emergency department) and Sexual Assault Forensic Examiner (SAFE) Program Center of Excellence.

Kings County serves the boroughs of Brooklyn and Staten Island, with over 510,000 clinic visits and 140,000 emergency department visits in 2015.[1] The hospital provides services to more than 800,000 people in the surrounding communities, including 415,650 in the primary service area of Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brownsville, Crown Heights, Canarsie, East Flatbush, East New York, Flatbush, and Prospect Lefferts Gardens. Ethnic diversity among the mostly black and Hispanic population served (94%) by Kings County is high, with large populations from the Caribbean as well as South American and African countries. Accordingly, Kings County employees speak 39 different languages to meet this diverse population's needs.[3]

History

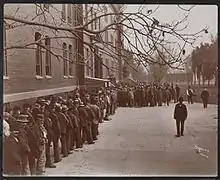

Kings County Hospital was born of necessity, dedicated to caring for the underprivileged of Brooklyn. In 1824, New York State established a law requiring several counties, including the County of Kings (Brooklyn), to purchase lands to be used exclusively to house the poor, deferring all potential real estate taxes which could be levied on the land. The law stated that taxation of the surrounding inhabitants would be used to fund these projects.[4]

The hospital was then established in 1830 as Brooklyn County Almshouse.[5] The first hospital building was constructed in 1837, after land was purchased from the Martense family for three thousand dollars.[6]

In 1857, an investigation was initiated by the temporary president of the State Senate, Mark Spencer, to visit all establishments created by the 1824 law. The investigation surveyed the Brooklyn County Almshouse, finding a hospital and lunatic asylum among other buildings constructed since the creation of the law. The hospital was a four-story 48 by 254 foot building housing 430 patients and lunatic asylum “260 feet long, wings 45 feet, and the centre 80 feet wide, four stories high” built to accommodate 150 patients but housing 205. At the height of the straitjacket, the lunatic asylum did not employ the use of physical restraints for patients, allowing them to freely mingle and take exercise at their leisure – “The resident physician observed that he considers 'kindness' more potent than chains”. The hospital and asylum each employed a single physician to care for all housed patients.[7] Famously in 1864, Walt Whitman committed his brother to the asylum. The mid-20th century was fruitful for public health and scientific advancement at Kings County. Some of the first successful large-scale family planning services in the country were started under renowned physician Louis Hellman. It began with his fight against a ban on family planning services in New York public hospitals in 1958. In 1965, due chiefly to efforts organized by Dr. Hellman, the New York State legislature lifted the ban on the prescription of birth-control medications in public hospitals in New York State. By 1966, it was demonstrated that these efforts were highly successful in lowering abortion rates, establishing a nationwide precedent. These efforts radically changed the availability for birth control among underserved and impoverished communities.[8]

Working with populations in which sickle cell anemia was endemic, in 1966, Drs. Margaret G. Robinson and R. Janet Watson observed a high incidence of pneumococcal meningitis in sickle cell patients – a similar rate to that of post-splenectomy patients. Upon this conclusion they developed the first explanation for such a similarity being inability of macrophage phagocytosis in these encapsulated bacteria.[9] These results were paramount in establishing the practice of vaccinating patients with sickle-cell anemia against encapsulated bacteria.

In 1997, Kings County began a modernization program.

- Phase I – a 250,000 sq ft (23,000 m2) bed tower was completed in 2001

- Phase II – a 260,000 sq ft (24,000 m2) treatment and diagnostic center was completed in 2005

- Phase III – an ambulatory center, was added in 2006

This work was managed by the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York, with the Gilbane/TDX Joint Venture as the Construction Manager. A 300,000 sq ft (28,000 m2) Behavioral Health Center was added in 2008.

In 2003, the US Army established a training program at the hospital called the Academy of Advanced Combat Medicine to train reservists in an emergency department that has received 600 cases per year of gunshot and stabbing victims.[10]

Services

The hospital offers a wide range of services – women's health, child & teen health, ambulatory care, behavior health, diagnostic services and surgical services.[11]

Kings County Hospital has an extensive history treating acutely injured patients and publishing in the field of trauma surgery, as early as 1906, on the subject of surgical management of epidural hematomas by C.F. Barber, a surgeon at the hospital.[12] The hospital has claimed many other "firsts" in the field of medicine, For instance, it was the site of the first open-heart surgery performed in New York State; NYC Health+Hospitals/Kings County physicians invented the world's first hemodialysis machine, conducted the first studies of HIV infection in women and produced the first human images using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[13]

Due to Kings County Hospital's prestige, many New York City Police Department officers reportedly prefer to get sent to the hospital if they get shot.[14]

Controversy

Kings County Hospital has paid out more than 1⁄3 of all medical malpractice claims against the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation (over $60 million). Since there are 11 city hospitals, this indicates that the hospital has a very high rate of malpractice claims compared to other city hospitals. It has been the most-sued hospital of the city's health care system.[15] Kings County has also been criticized as having the longest emergency room wait of all public hospitals in New York City, with an average wait of 90 minutes for non-life-threatening conditions.[16]

On June 19, 2008, Esmin Green, a 49-year-old native of the Caribbean country of Jamaica, died in the waiting room of the hospital's G Building, a psychiatric ward, which resulted in several people being fired, as well as investigations and lawsuits. The incident came in the midst of a federal lawsuit charging neglect by the hospital.[17][18]

After seven years of oversight, the United States Department of Justice declared the hospital a model program for the treatment of behavioral health conditions.[19]

References

- "About NYC Health + Hospitals/Kings County". City of New York. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- "History". City of New York. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- "2013 Community Health Needs Assessment" (PDF). www.nyc.gov. Health and Hospitals Corporation of New York City. 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- "1824 LAW". www.poorhousestory.com.

- Brooklyn Historical Society. "Brooklyn County Almshouse Questionnaire". Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- "History - Kings County Hospital Center". www.nyc.gov.

- "POORHOUSE History of Kings-Brooklyn County". www.poorhousestory.com.

- Yerby, Alonzo (1966). "Public Policy in Regard to Birth-Control Services". New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society. 275 (15): 824–826. doi:10.1056/NEJM196610132751507. PMID 5916183.

- Robinson, Margeret; WAtson, Janet (1966). "Pneumococcal Meningitis in Sickle-Cell Anemia". New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society. 274 (18): 1006–1008. doi:10.1056/NEJM196605052741806. PMID 5909733.

- Bleyer, Jennifer (December 6, 2005). "Battlefield Medics Shaped in Civilian Setting". The New York Times. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- "HHC - Services - Kings County Hospital Center". www.nyc.gov.

- Barber, C.F. (1906). "A More Careful Diagnosis in Head Injuries" (PDF). Brooklyn Medical Journal. 20 (12): 351–352. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- "History". Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Andy Newman (July 15, 2007). "In Hospital Scrubs and Officer's Blues, a Kinship". The New York Times. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- "Kings County Hospital Facing Another Lawsuit". WNYC – News. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- Blau, Reuven (December 2, 2018). "Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn has the longest emergency room wait of city hospitals". nydailynews.com. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- Marzulli, John (June 30, 2008). "Hospital video shows no one helped dying woman". New York Daily News.

- "Video shows death of US patient". bbc.co.uk. BBC. July 2, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story, Joseph P. Merlino, Joanna Omi, Jill Bowen, Oxford University Press, Jan 8, 2014 - Medical - 256 pages.