Kings Langley Palace

Kings Langley Palace was a 13th-century Royal Palace which was located to the west of the Hertfordshire village of Kings Langley in England. During the Middle Ages, the palace served as a residence of the Plantagenet kings of England.[1] It fell into disuse sometime during the 16th century and became a ruin. Today, nothing remains of the building except for some archaeological remains. The site is a scheduled ancient monument.[2]

| Kings Langley Palace | |

|---|---|

Former site of Kings Langley Palace | |

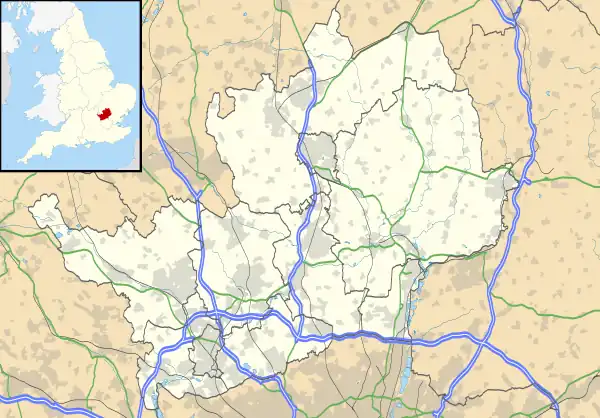

Former location of the Palace in modern Hertfordshire | |

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Type | Palace |

| Town or city | Kings Langley, Hertfordshire |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°42′43″N 0°27′32″W |

| Estimated completion | 1277 |

| Demolished | 17th century |

History

The origins of Kings Langley Palace are not known, but it is thought that the estate land was originally the property of the Manor of Chilterne Langley or Langley Chenduit. The estate would have part of a large, dense forest stretching from London out to Berkhamsted which was abundant in deer, and a hunting lodge is known to have existed on the estate during the reign of Henry III. The Manor became a royal possession in 1276 when Queen Eleanor of Castile, wife of King Edward I ("Edward Longshanks"), acquired the estate and supervised the development of a lavish royal household. There are records of a "new start" in 1277, and these are thought to be either improvements to an existing property or a new house being built at the top of the hill.[3][4] Little is known about the early development of the palace, but records exist from 1279-1281 which indicate that the palace had private chambers for the Edward I and Eleanor and for their son, Alphonso, Earl of Chester.[5]

King's Langley Palace served as a family home for Edward and Eleanor. Their son, Edward of Caernarfon (later King Edward II), who was born in Caernarfon Castle in 1284, spent much of his youth at Langley Palace. Prince Alfonso, heir to the throne, died only months after the young Edward's birth, and Queen Eleanor died unexpectedly in 1290. With Prince Edward now heir to the throne, Langley Palace was destined to be inherited by the young prince. After Eleanor's death, the King took residence at Ashridge and held Parliament there in 1290 and 1291. In 1299 the aging King Edward I remarried to Margaret of France, granting her Berkhamsted and Hertford Castles, and he returned to Langley. That same year, he summoned the Bishop of Norwich, John Salmon, John of Berkhamsted, Abbot of St Albans, and Aymon, Count of Savoy, to celebrate the feast day of All Saints with him and Queen Margraret at King's Langley.[6]

After Prince Edward was invested as Prince of Wales, King Edward I granted Langley to him in 1302. The young prince was enthusiastic about music, the arts, horse racing and kept a small menagerie, which included a lion and a camel, at Langley. He also allowed his favourite, Piers Gaveston, to live with him at the palace, a companionship which scandalised England at the time.[3][7] In 1307 Edward II was crowned king and founded the neighbouring King's Langley Priory in 1308 in the park of his manor adjacent to the palace. It was here that King Edward reburied his beloved Gaveston in January 1315 following his execution. Langley Palace remained the King's favourite residence until his death in 1327.[8] Today, no traces of the monastery church or Gaveston's tomb remain.[4][9]

.jpg.webp)

During the reign of Edward III, his fifth son, Edmund of Langley was born in Langley Palace in 1341 and drew his name from the manor. After his death in 1402, Edmund was buried in the priory there.[10] In the late 1340s, England was being ravaged by the spread of Black Death; with high death rates in London, Edward III moved his Court out of the city to Langley Palace in July 1349, and for a short period the seat of government was based in Kings Langley.[6] Edward also removed his extensive collection of religious relics from the Tower of London and brought them to Kings Langley for safekeeping.[11]

The author of The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer, would have visited the palace during his appointment as Clerk of the Kings Works to King Richard II between 1389 and 1391.[12]

Later King Richard II celebrated Christmas there.[6] The Palace was damaged by a serious fire in 1431;[13] accounts describe "a great and disastrous fire at the manor of our lady Joan the Queen at Langley" (referring to Joan of Navarre, wife of Henry IV) which was blamed on "the negligence and drowsiness of a ministrel and insufficient care of a lighted candle."[14] However, records of subsequent repair work to the buildings indicate that the palace was not entirely destroyed by the fire.[15] The last evidence of the Palace being used for official occasions was in 1476 when William Wallingford, Abbot of St Albans Abbey, held a banquet there for the Bishop of Llandaff.[6]

The manor was transferred to Eton College but reverted to the Crown, for Henry VIII conveyed it upon Catherine of Aragon, whom he was about to marry. During Henry's reign, a new class of landowner emerged; instead of estates being held by powerful feudal lords who were often a challenge to the sovereign, estates were now being granted to servants of the crown. Holders of high office were granted freehold land as a reward from the king, and they used their new property as a source of income. John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford, was given custody of the royal park at Kings Langley in 1538, one of many perquisites he accumulated at the court of Henry VIII. The park was acquired by a wealthy lawyer, Sir Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal of England and the builder of Old Gorhambury House near St Albans.[16]

During the reign of Charles I, Kings Langley royal park was cleared to make way for agriculture and tenant farmers cultivated the land. By 1652 there were 10 farmers on the estate.[17] In 1626, Charles I granted the Langley Estate to Sir Charles Morrison, owner of the Estate of Cassiobury at nearby Watford who already held a lease on part of the land at Langley. Upon his death in 1628, the estate passed to his daughter, Elizabeth Morrison and her husband Arthur Capell, 1st Baron Capell of Hadham. Capell, a Royalist in the English Civil War was executed in 1649, and the estate was granted to a Parliamentarian, Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex. Following the Restoration, the Langley Estate was returned by the Crown to the Capell family, granting it to Capell's son Arthur Capell and also creating him Earl of Essex.[18]

In the late 17th century the expansion of the London population meant that landowners in the surrounding country were increasingly turning their land to agricultural use, to meet the demand for food and animal feed. Many parks eventually disappeared; Kings Langley Park did not feature on a 1675 map drawn by John Seller.[17]

The estate of Langley Palace remained in the possession of the Earls of Essex until 1900, when the 7th Earl, George Capell, sold the land to a Mr. E. N. Loyd of Langleybury.[6][19]

Remnants of the Palace complex remained for many years after it ceased to be a royal residence, falling gradually into decay. The gatehouse and parts of the main building were still standing in 1591, and in his 1728 History of Hertfordshire, Nathanael Salmon states that "Here the rubbish of royalty exists" in reference to Kings Langley.[6] James Sargant Storer's 1816 account features an illustration of the "Remains of an Ancient Palace Kings Langley Herts" which is said to be a farm house which "exhibits the ancient bake-house and some other vestiges of the domestic offices of the palace."[20] A description published by John Murray in 1895 reports that "at Kings Langley some outer walls only exist of the once royal palace, erected by Henry III."[21]

Today, nothing remains of the royal palace; the site was occupied by the Rudolf Steiner School, which closed in March 2019.[13] A small display case of items from the Palace era recovered during excavation could previously be seen in the school entrance hall. Buildings from King's Langley Priory were also used by the Steiner School.[22] Some ruins exist in the vicinity; ruined flint walls and fragments of stonework remain in the garden of house number 80, Langley Hill, which are thought to be part of a house built for Sir Charles Morrisson around 1580 when he held a lease on the Crown land.[23]

Architecture

The Palace had a triple courtyard layout.[24] Accounts dating from August 1279 to November 1281, shortly after the estate became a royal possession, describe building work on the house which encompassed construction of chambers for the king and queen and for their son, Alphonso, Earl of Chester, paving the queen's cloister, planting of a vineyard, digging of a well and expansion of a moat. Further records list the construction of a new gateway (1282–1283); a wine cellar (1291–1292); louvres for the roof of the hall built by a carpenter, Henry of Bovingdon; a stone wall enclosing the court (1296–1297); and the addition of new fireplaces in two "great chambers". The palace had a bath-house, domestic offices, a bakery, roasting house, great kitchen and "le Longrewe" ("the long house").[5] Between 1359 and 1370, further additions were made to the palace, which included a bath house and a new entrance gate at a cost of £3000, and Totternhoe Stone was used to pave the bath house and for a fireplace in the King's chamber.[10][25]

It appears from excavations in 1970 that the Palace also had a huge underground wine cellar, situated under the present-day gymnasium;[13][26] this cellar is thought to have been built around 1291–1292 and was located on the west side of a kitchen court, opposite a bakehouse. Excavations also revealed the presence of a structure to the east of this which is thought to be a probable gatehouse.[27] This gatehouse opened out onto an approach road, now known as Langley Hill. Because the kitchens were located on the west side of the site, it is thought that the great hall of the palace ran on an east-west alignment.[28]

Records exists stating that a brickmaker to the king, William Veyse, was appointed in 1437 to produce bricks for Kings Langley Palace. In 1440 bricks from le Frithe, near St Albans, were used to make fireplaces and ovens in the Palace, possibly as part of repair works following the fire of 1431. Veyse was also appointed in 1440 to supply bricks for a stone wall at the Tower of London.[14]

In Literature

Act III, scene IV of William Shakespeare's play Richard II is set in the gardens of Kings Langley Palace, in which Queen Isabel learns of King Richard's imprisonment.[29]

References

- (Storer 1816, p. 718)

- Historic England. "Royal Palace (site of) (1005252)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- "History of the Royal Palace". Kings Langley Local History & Museum Society. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- (Neal 1977)

- (Neal 1977, pp. 125–6)

- "Parishes: King's Langley". British History Online. Victoria County History. 1908. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- (Shields 2013)

- May McKusack, The Fourteenth Century (Oxford History of England) 1959.2.

- Walter Phelps Dodge, Piers Gaveston: a chapter of early constitutional history, 1899:179; May Kusack, The Fourteenth Century (Oxford History of England) 1959:47;

- (Emery 2000, p. 257)

- Sloane, Barney (2013). The black death in London. New York: The History Press. ISBN 9780752496399. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Sheilds, Pamela (2009). Hertfordshire Secrets and Spies. Stroud: Amberley. p. 15. ISBN 9781848687882.

- "Kings Langley Palace". The Dacorum Heritage Trust. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- "The Brickmakers of St Albans". Hertfordshire Genealogy. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- (Neal 1977, p. 126)

- (Prince 2008, p. 16)

- (Prince 2008, p. 32)

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Essex, Arthur Capel, 1st Earl of". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 781–782.

- Shirley, Evelyn Philip (1867). Some Account of English Deer Parks: With Notes on the Management of Deer. J. Murray. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- (Storer 1816, p. 717)

- Handbook for Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, and Huntingdonshire. John Murray. 1895. ISBN 9781167108068.

- Lionel M, Munby, The History of Kings Langley

- "Ruins of Langley Palace in the Garden of No 80 (York Ridge), Kings Langley". British Listed Buildings. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Anthony Emery (1996). Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300-1500: Volume 2, East Anglia, Central England and Wales. Cambridge University Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-521-58131-8.

- Brown, Julian Munby, Richard Barber, Richard (2008). Edward III's Round Table at Windsor: The House of the Round Table and the Windsor Festival of 1344. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. p. 55. ISBN 9781843833918. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - John Steane (2003). The Archaeology of the Medieval English Monarchy. Taylor & Francis. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-203-16522-5.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (2002). Hertfordshire (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 217. ISBN 9780300096118. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- (Neal 1977, p. 143)

- Forsyth, Mary (2015). "2: the Medieval Town". Watford: A History. The History Press. ISBN 9780750966481. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

Bibliography

- Storer, James Sargant (1816). "Abbey at King's Langley, Hertfordshire". the Antiquarian Itinerary. London. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- Neal, David (1977). "Excavations at the Palace of Kings Langley, Hertfordshire 1974-1976" (PDF). Medieval Archaeology. The Society for Medieval Archaeology. 24. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Shields, Pamela (2013). Royal Hertfordshire Murders and Misdemeanours. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1445630571. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- Prince, Hugh (2008). "II: Elizabethan Parks". Parks in Hertfordshire since 1500. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780954218997. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Emery, Anthony (2000). "King's Langley Palace". Greater medieval houses of England and Wales, 1300-1500. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. p. 257. ISBN 9780521581318. Retrieved 28 November 2015.