Dunduff Castle

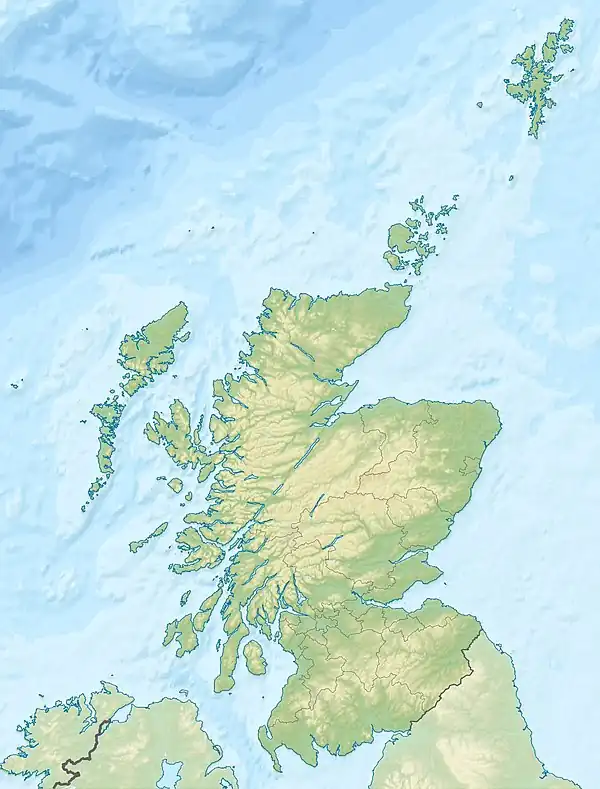

Dunduff Castle is a restored stair-tower in South Ayrshire, Scotland, built on the hillside of Brown Carrick Hills above the Drumbane Burn, and overlooking the sea above the village of Dunure.

| Dunduff Castle | |

|---|---|

| Dunduff, South Ayrshire, Scotland GB grid reference NS2719216370 | |

Dunduff Castle from the south, following restoration | |

Dunduff Castle | |

| Coordinates | 55.410704°N 4.731241°W |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Private |

| Open to the public | No |

| Condition | Restored |

| Site history | |

| Built | Circa 1696 |

| In use | 17th century |

| Materials | Stone |

History

As a place name Dunduff may contain the Gaelic elements for "hill" or "fort" and "stag", as in Dundaff near Fintry.[1] Other suggestions are that Duff is a personal name, therefore "Fort of Duff"[2] or "Black Hill Fort" from the Gaelic 'Dun Dùbh.[3]

Glennie identifies Dunduff Castle with Dindywydd, a site mentioned by Aneirin or Neirin, a Dark Age Brythonic poet, in one of his Arthurian poems as preserved in a late 13th-century manuscript known as the Book of Aneirin.[4]

Castle ruins

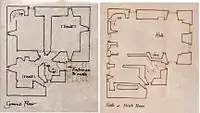

Lying to the east of Dunduff Farm on a rocky knoll, this tower castle was built to an L-shaped plan, with a square three floored stair-tower[5] in the re-entrant angle on the south. Three barrel-vaulted chambers are on the ground floor and these were accessed via the lobby of the tower. A private chamber on the first floor was accessed by a corridor that ran the length of the main block. A fireplace in the wing heated the hall, with its splayed window embrasure. An intermediate floor once existed, as indicated by joist sockets. Window and door features of the original ruin suggest construction in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.[6]

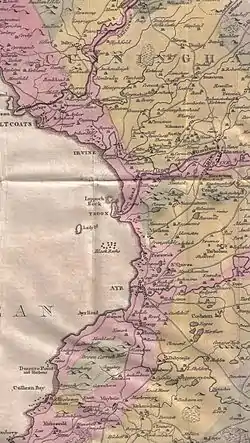

The General Roy map of 1747–1755 shows a Dunduff Mill associated with the castle; this mill is also recorded in a charter of 1581.[7][8] William Aiton's map of 1808 shows Dunduff Castle, however it is not annotated as a ruin, although Dunure is.[9]

Groome refers to the ruin in 1903 as a baronial fortalice.[10]

Abandonment

In 1696 the castle was recorded as being nearly finished.[5][11] Smith sees it as having been left unfinished.[12][13] The cartographers show a Dunduff Castle as entire from Pont's maps (1560–1614)[14] until the advent of Armstrong's map of 1775, which marks Dunduff as a ruin.[15]

There is therefore some considerable doubt that Dunduff Castle was ever completed.[16] Abercrummie in A Description of Carrict [17] lists Dunduff among the houses of the Gentry in Carrick as "a house on the coast never finished".

In 1891 the Rev R Lawson in his book, Places of Interest about Maybole with Sketches of Persons of Interest,[18] states:-

On the hill side above stand the ruins of the unfinished castle of Dunduff a local illustration of that searching question of our Lord's—" Which of you, intending to build a tower, sitteth not down first and counteth the cost, whether he have sufficient to finish it Lest haply, after he hath laid the foundation, and is not able to finish it, all that behold it begin to mock him, saying, This man began to build and was not able to finish."

Restoration

The ruins were consolidated and the tower completely restored for use as a family residence in the 1990s.[11][19] Ian Begg produced the design for the restoration.[20]

Lairds and lands of Dunduff

It is recorded that Sir John de Graham was born on the lands of Dunduff in 1298. During the Wars of Scottish Independence he fought alongside Sir William Wallace and was killed at the Battle of Falkirk where the Scottish army was routed by King Edward I. He was buried at the Falkirk Old Parish Church in Stirlingshire. The poet Robert Burns visited his grave in 1787.[21]

Smith[12] sees Dunduff as having been a castle of the Kennedy clan and their septs, together with the other castles in the area, namely Greenan, Dunure, Kilhenzie, Doonside, Sauchrie, Craigskean, Beoch, Auchendrane, Garryhorne, Brockloch, and Smithstone. To make the point he quotes:

|

The first written record of Dunduff is in the reign of William the Lion (1165–1214) at which time Walter Champenais de Karrig made a grant of land at Dunduff to the monks of Melrose.[22]

In 1581 the properties associated with Dunduff are the 12 merk lands, the grain mill of Dunduff, the 10 merk lands of Glentig, with its grainmill, the 5 and a half merk lands of Mekill Sallauchan, and the 4 merk lands of Little Sallauchan.[23]

Stewart lairds

The first Laird of Dunduff was William Stewart, married to Isobel Ker. In 1528 he was the Scottish Ambassador to France as appointed by James V; he died in 1552.[25] His father was Sir Andrew Stewart, second Lord Evondale, first Lord of the Bedchamber to King James IV. The family traced its line directly to King Robert II of Scotland.[26]

The next record is that of William Stewart, second Laird of Dunduff in 1558, his wife being Elizabeth Corry. The correct family name seems to have been Stewart, however they often used the name Dunduff as a surname. Paterson speculated that they obtained the property through marriage with an heiress with the surname Dunduff. Matthew, third laird, was born at Dunduff in 1560, inherited the property from his father William in 1580, and is referred to as "Dunduff of that Ilk".

In the 16th century the master of Cassilis (younger brother of the earl) enter into a bond with the laird of Dunduff (Matthew Stewart) and the laird of Auchindraine to murder his brother, the Earl of Culzean; all three had suffered at his hands.[27] Thomas Kennedy of Bargany, who liberated Alan Stewart Commendator of Crossraguel from Gilbert Kennedy, Earl of Cassilis, and the "black vault" of Dunure, was an ancestor of the Lairds of Dunduff.[25]

The Laird of Bargany then had an unsuccessful property dispute with the earl over the lands of Newark,[28] which resulted in a fourth member joining the group and an attempt on the life of Culzean being made.[29] On 1 January 1598 the earl dined at supper with Sir Thomas Nasmyth at Maybole and the plotters and their servants lay in wait, however despite eight shots being fired at him, the earl escaped unharmed, having run away through the streets of Maybole with the benefit of a dark and murky night for concealment. The earl's brother, the Master of Cassillis, was one of those involved, together with Mure of Auchendrayne.[28]

The result of this incident for the Laird of Dunduff was that he was held briefly in Edinburgh Castle and was then banished from Scotland, England, Ireland and all the Isles and fined 1000 merks.[29][30] This sentence was either evaded or not enforced and upon his return the laird and the earl settled their disagreements and became friends; he died in 1609.[31] George, brother of Matthew was murdered by John Glendoning of Drumraschein 1601.[30]

William Stewart, the fourth laird inherited the lands from his father. In 1668, it is recorded that the John, the fifth (and last) Stewart Laird of Dunduff and his brother William were prevented, being opposed to Oliver Cromwell and supporting the crown, from renewing the covenant and shortly after the property was sold and passed into the hands of the Whiteford family.[32] John's sister inherited Mount Stewart and her daughter was Alice, Countess of Wicklow.

Whiteford or Whitefoord lairds

The family of Quhitefoord or Whiteford held lands of this name in the south-east of Paisley until 1689. Originally Walter was given the lands of Whitefoord by Alexander III, following his actions at the Battle of Largs in 1263.[33] James Whiteford of Dunduff (d 1697) married Isabel Blair, a daughter of Sir Bryce Blair of that Ilk. Another James Whiteford is recorded in charters of 1700 and 1714; a Bryce Whiteford of Dunduff and Cloncaird (d 1726) married Elizabeth Cuninghame, daughter of Sir David Cuninghame of Cloncaird.[34]

A James Whiteford of Dunduff held lands at Drumfadd in 1757 and a Lady Dunduff, widow of Bryce Whiteford before 1750, is recorded as living in Ayr in 1767, dying in 1775 at the age of 85.[32][35] The title 'lady' was often given as a mark of respect to elderly widows whose husbands were not ennobled, such as the wives of lairds.[36] The family possessed other estates at one time, such as Blairquhan Castle, then known as Whiteford Castle, Whitefoord Tower, Cloncaird Castle and Ballochmyle.[33][37] The family now live in Shropshire, England.[33]

A Walter Whyteford (Sic) became Laird of Fail in 1619, the grant to him of the old Fail monastery being ratified in 1621 by parliament. The Wallaces of Craigie had expected to inherit the property.[38]

Irish connection

William Stewart, 4th Laird of Dunduff, was born circa 1580 and became a baronet. Sir William had applied for land in Ulster during the Plantation of Ulster and was granted 1,000 acres (400 hectares);[39] this was during the 'plantation period' under King James VI of Scotland (James I of England). These lands were in County Donegal known as Coolaghy in the Barony of Raphoe, known as Fort Dunduff and later as the Manor of Mount-Stewart. Sir William had the power to create tenures, and to appoint court baron and court leet.

Mount-Stewart passed to the family of the Alice Howard, 1st Countess of Wicklow.[25]

Mount-Stewart in Donegal should not be confused with Mount Stewart in County Down, Northern Ireland, which was latterly the home of the Vane-Tempest-Stewart family, Marquesses of Londonderry.

Dunduff Mill

Matthew Dunduff aka Stewart obtained possession of the Dunduff corn mill in 1581. The mill was powered by one of the burns running off the Brown Carrick Hill, but its exact location is unknown. Dunduff Mill was driven by a breast paddle and a single pair of stones. The sifting and blowing of the husks were done by hand as the mill had no blowers or mechanical sieves.[40]

Associated archaeology

Dane's Hill

Smith and others record an Iron Age fort or motte with this name on a separate rocky knoll about 170 metres (560 feet) west of the castle. The structure has a medial ditch, once of significant depth and two ramparts; its sides are precipitous and rocky, except next to the rampart. A local tradition states that he Danes fought here[2][11] and also associates the Danes with the construction of a castle at Dunure.[41]

Finds

A crown-size coin of Albert and Elizabeth of Bruges and Brabant (c. 1630) was ploughed up near Dunduff Castle.[42]

Dunduff Creek

The exact location has been lost, but in 1655 a Dunduff Creek is recorded as being in use as a small harbour between Dunure and the Heads of Ayr.[42]

Kirkbride

To the west of the castle, just beyond Dunduff Farm, are the rectangular shaped ruins of the pre-reformation church, dedicated to St Brigid, the Irish Saint from Kildare, who lived c.453–525 Other Ayrshire dedications included Giffen and Trearne, Irvine, Sundrum, Ardrossan, West Kilbride and South Kilbride near Stewarton. Kirkebride at Larges (sic) had belonged to the Cistercian foundation of St Mary of North Berwick, together with 52 acres (21 hectares) of land and a salt pan. The name 'Larges' was the secular name of the area and was once used to describe much of the old parish; it survives in the name of Largs Farm.[43]

In 1928, amongst the rubble, a cross was found carved on a slab. The stone had a chamfered edge and the cross bore an unusual lozenge-shape, cut out at the centre. It may have been the consecration stone of the chapel and was dated as possibly 12th century. The whereabouts of this cross is at present unknown.[43]

The church was abandoned after the parish of Kirkbride merged with that of Maybole and was ruinous by 1696.[43] In 2010 only some ruins remain together with the churchyard and its gravestones.[20] A field next to the church is known as the "Priest's Land", and Groome states that the cemetery was still in use as late as 1903.[10]

References

Notes;

- Johnston, Page 110

- Smith, Page 176

- "Place Names Accessed : 2010-03-06" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- Glennie, Page 81

- Close, Page 167

- RCAHMS Record Accessed: 2010-03-06

- Paterson, Page 429

- Roy Map Accessed : 2010-03-06 Archived 18 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Aiton, Map

- Groome, Page 428

- Campbell, Page 175

- Smith, Page 182

- Dougal, Page 88

- Timothy Pont Accessed : 2010-03-06

- Captain Armstrong Accessed : 2010-03-06 Archived 4 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Gazetteer for Scotland

- Abercrummie, W. (1696). A Description of Carrict

- Archived 2 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine Lawson, R. (1891). Places of Interest about Maybole with Sketches of Persons of Interest

- Pictures of Dunduff Castle

- Love, Page 298

- Mackay, Page 335

- Paterson, Page 428

- AWAA, Page 167

- Aiton, Map insert

- "Royal House of Stewart Accessed : 2010-03-06". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- "The Royal House of Stewart Accessed : 2010-03-06". Archived from the original on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- Paterson, Page 45

- MacArthur, Page 58

- Paterson, Page 46

- Paterson, Page 430

- Paterson, Page 50

- Paterson, Page 431

- Coventry, Page 595

- Whiteford Genealogy Accessed : 2010-03-06

- Ayr & its People Accessed : 2010-03-06

- James McAdam Accessed : 2010-03-06

- Whiteford Genealogy Accessed : 2010-03-07

- Paterson, Page 33

- Ulster Ancestry Accessed : 2010-03-06

- Wilson, Page 73

- Harvey, Page 30

- Scotland's Places Accessed : 2010-03-06

- Kirkbride by A. Hendry : Accessed : 2010-03-07

Sources;

- Archaeological & Historical Collections relating to the counties of Ayrshire & Wigtown. Edinburgh : Ayr Wig Arch Assoc. Vol. VI. 1889

- Aiton, William (1811). General View of The Agriculture of the County of Ayr; observations on the means of its improvement; drawn up for the consideration of the Board of Agriculture, and Internal Improvements, with Beautiful Engravings. Glasgow.

- Abercrummie, William (1696). Carrick in 1696. Maybole Historical Society. 2003.

- Aiton, William (1811). General View of the Agriculture of the County of Ayr. Glasgow.

- Campbell, Thorbjørn (2003). Ayrshire: A Historical Guide. Edinburgh : Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-267-0

- Close, Robert (1992), Ayrshire and Arran: An Illustrated Architectural Guide. Pub. Roy Inc. Arch Scot. ISBN 1-873190-06-9.

- Coventry, Martin (2010). Castles of the Clans. Musselburgh : Goblinshead. ISBN 1-899874-36-4.

- Crawford, Archibald (1844). The Brownie of Dunure. Ayrshire Wreath MDCCCXLIV. Kilmarnock : H. Crawford & Son.

- Dougall, Charles S. (1911). The Burns Country. London : A & C Black.

- Glennie, John S. Stuart (1869). Arthurian Locations. Edinburgh : Edmonston & Douglas.

- Graham, Angus (1984). Old Ayrshire harbours. Ayrshire collections, v. 14, no. 3. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc

- Groome, Francis H. (1903). Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland. V.1 London : Caxton

- Harvey, William. Picturesque Ayrshire. Dundee : Valentine & Sons.

- Johnston, J. B. (1903). Place-names of Scotland. Edinburgh : David Douglas.

- Lawson, R. (1891). Places of interest about Maybole, with sketches of persons of interest. Paisley : J. and R. Parlane.

- Love, Dane (2003). Ayrshire : Discovering a County. Ayr : Fort Publishing. ISBN 0-9544461-1-9.

- MacArthur, Wilson. (1952). The River Doon. London : Cassell & Co. Ltd.

- Mackay, James (2004). Burns. A Biography of Robert Burns. Darvel : Alloway Publishing. ISBN 0907526-85-3.

- Paterson, James (1863–66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V. – III – Carrick. Edinburgh: J. Stillie.

- Salter, Mike (2006). The Castles of South-West Scotland. Malvern : Folly. ISBN 1-871731-70-4.

- Smith, John (1895). Prehistoric Man in Ayrshire. London : Elliot Stock.