Kirkdale sundial

The Saxon sundial at St Gregory's Minster, Kirkdale in North Yorkshire, near Kirkbymoorside, is an ancient canonical sundial which dates to the mid 11th century.

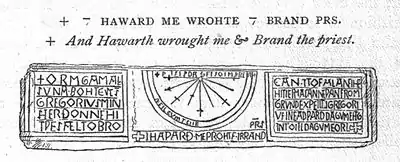

The panel containing the actual sundial above the church doors is flanked by two panels, bearing a rare inscription in Old English, the language of the Anglo-Saxons. The sundial, discovered during a renovation in 1771, commemorates the rebuilding of the ruined church, about the year 1055, by Orm, son of Gamal, whose Scandinavian names suggest that he may have been a descendant of Vikings who overran and settled this region in the late 9th century. [2]

Inscription

The inscription on the sundial reads as follows:

- + ORM GAMAL / SVNA BOHTE SCS / GREGORIVS MIN / STER ÐONNE HI / T ǷFS ÆL TOBRO // CAN ⁊ TOFALAN ⁊ HE / HIT LET MACAN NEǷAN FROM / GRVNDE ΧΡE ⁊ SCS GREGORI / VS IN EADǷARD DAGVM CNG / ⁊ [I]N TOSTI DAGVM EORL +

- Orm Gamal suna bohte Sanctus Gregorius Minster ðonne hit wæs æl tobrocan and tofalan and he hit let macan newan from grunde Christe and Sanctus Gregorius in Eadward dagum cyning and in Tosti dagum eorl.

(ǷFS may be an error for ǷES, though if the letters were originally painted, as seems quite possible, the E may have appeared intact. The Anglo-Saxon character '⁊' is one of the Tironian notes and stands for the conjunction 'and' (functionally equivalent to the ampersand). Several characters in the Anglo-Saxon alphabet but no longer used in English appear in the inscriptions. Ð/ð (called 'eth')is equivalent to modern 'th', as also is þ (called 'thorn'). Ƿ (called 'wynn') is equivalent to modern 'w'; and Æ/æ (called 'ash') is here equivalent to modern 'a').

- "Orm son of Gamal bought St Gregory's Minster when it was all broken down and ruined and he had it made anew from the ground for Christ and St. Gregory in the days of Edward the king and in the days of Tosti the earl."[3]

The sundial itself is inscribed

- + ÞIS IS DÆGES SOLMERCA + / ÆT ILCVM TIDE

- þis is dæges solmerca, æt ilcum tide.

- "This is the day's sun-marker, at every tide."

And at the bottom of the central panel is the line

- +⁊ HAǷARÐ ME ǷROHTE ⁊ BRAND / PRS

- and Hawarð me wrohte and Brand presbyter(i) [or preostas] .

- "And Haward wrought me and Brand priest(s)."[3]

The reference is to Edward the Confessor and Earl Tostig, Edward's brother-in-law, who was the son of Earl Godwin of Wessex and the brother of Harold. Tostig held the Earldom of Northumbria from 1055 to 1065, fixing the date of the church's reconstruction to that decade. He is also known for the murder of Gamal, Orm's father. The language of the inscription is late Old English, with a failing case and gender system. The compound solmerca is otherwise unattested in English, and has been ascribed to Scandinavian influence (Old Norse solmerki 'sign of the zodiac').[4][5]

The Historic England Web site, which lists St Gregory's as Grade I, provides the following translation of the full, three part inscription: "Orm Gamal's son bought St. Gregory's Minster when it was all broken down and fallen and he let it be made anew from the ground to Christ and St. Gregory, in Edward's days, the king, and in Tosti's days, the Earl. This is day's Sun marker at every tide. And Haworth me wrought and Brand, priests."[6] The last two sentences are more fully translated by some sources as: "This is the day’s sun-marking at every hour. And Hawarth made me and Brand priest(s)"[7][8][9]

The Journal of the Yorkshire Archaeological and Historical Society. (Volume 69), published in 1997, offers more persuasive interpretations of the final sentence: "First, it makes two statements: that Hawarth made the sundial (that is, he was the craftsman), and that Brand was the priest. The second interpretation is that both Hawarth (who was probably a craftsman and could have been a priest) and Brand the priest (acting as his assistant or instructor), together made the sundial. Higgitt has suggested that 'Brand was perhaps responsible for the drafting and laying out of the text, and perhaps too for the design of the sundial'.27"[10] (The Higgitt referred to is John Higgitt who was a medieval scholar who specialized in analyses of Anglo-Saxon inscriptions. He contributed to a 1997 Medieval Archaeology journal report, Kirkdale - The inscriptions, 41. Vol 41, pp. 51–99.)[11][12][13]

Part of the sundial's historical significance is its testimony that, a century and a half after the Viking colonisation of the region, the settlers' descendants such as Orm Gamalson were now using English, not Danish or Norwegian, as the appropriate language for monumental inscriptions.[14]

Notes

- Wall, J. Charles (1912), Porches & Fonts.Pub. Wells, Gardner, Darton & Co., Ltd., London. P. 66.

- Goodall, John (October 2015). Parish Church Treasures: The Nation's Greatest Art Collection. Bloomsbury Continuum. p. 27. ISBN 9781472917645.

- Blair, John (2010). "The Kirkdale dedication inscription and its Latin models: ROMANITAS in late Anglo-Saxon Yorkshire". In Hall, Alaric; Timofeeva, Olga; Fox, Bethany (eds.). Interfaces Between Language and Culture in Medieval England: A Festschrift for Matti Kilpio. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers. p. 140. ISBN 978-90-04-18011-6.

- Kilpatrick, Kelly A. (16 September 2010). "St Gregory's Minster, Kirkdale, North Yorkshire". Project Woruldhord. University of Oxford. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Gibson, William Sidney (1846–1847). The history of the monastery founded at Tynemouth, in the diocese of Durham, to the honour of God, under the invocation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and S. Oswin, king and martyr, Vol. 1. London. pp. 15–17.

- Historic England. "ST GREGORYS MINSTER, Welburn (1149213)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal". Yorkshire Archaeological Society. 4 July 1997. Retrieved 4 July 2018 – via Google Books.

- Cuesta, Julia Fernández; Pons-Sanz, Sara M. (21 March 2016). The Old English Gloss to the Lindisfarne Gospels: Language, Author and Context. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 9783110447163. Retrieved 4 July 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Kirkdale". greatenglishchurches.co.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- https://archive.org/stream/YAJ0691997/YAJ0691997_djvu.txt, p=103

- "John Higgitt". Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Library". archaeologydataservice.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Watts, Lorna; Rahtz, Philip; Okasha, Elisabeth; Bradley, S. A. J.; Higgitt, John (1997), "Kirkdale—The Inscriptions" (PDF), Medieval Archaeology, 41: 51–99, doi:10.1080/00766097.1997.11735608

- [The Story of English episode 2 - The Mother Tongue — Part 4 / 7, PBS Documentary. See also discussion in S. A. J. Bradley, Orm Gamalson's Sundial (Kirkdale, 2002) and in M. Townend, Scandinavian Culture in Eleventh-Century Yorkshire (Kirkdale, 2009).

References

- David Scott and Mike Cowham Time Reckoning in the Medieval World – A study of Anglo – Saxon and early Norman Sundials. Great Britain, British Sundial Society 2010, pp. 46–46.

- Richard Fletcher, St. Gregory's Minster Kirkdale. Kirkdale: The Joint Church Council, 1990.

- James Lang, The Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture: York and Eastern Yorkshire, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1991.

- R. I. Page, How long did the Scandinavian language survive in England? The epigraphical evidence, In Clemoes and Hughes, eds. England before the Conquest: Studies in primary sources presented to Dorothy Whitelock. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 1971, pp. 165–181.

- S. A. J. Bradley, Orm Gamalson's Sundial : The Lily's Blossom and the Roses' Fragrance (The Kirkdale Lecture 1997). Kirkdale: Trustees of the Friends of St Gregory's Minster, 2002. ISBN 0-9542605-0-3.

External links

- The Kirkdale Sundial Retrieved 13 February 2012