Knossos (modern history)

Knossos (Greek: Κνωσός, Knōsós, [knoˈsos]), also romanized Cnossus, Gnossus, and Knossus, is the main Bronze Age archaeological site at Heraklion, a modern port city on the north central coast of Crete. The site was excavated and the palace complex found there partially restored under the direction of Arthur Evans in the earliest years of the 20th century. The palace complex is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete. It was undoubtedly the ceremonial and political centre of the Minoan civilization and culture.

Κνωσός | |

Royal road to Knossos | |

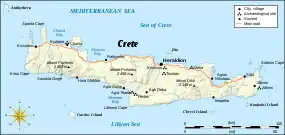

Crete, showing Heraklion, location of ancient Knōsos | |

| Alternative name | Cnossus |

|---|---|

| Location | Heraklion, Crete, Greece |

| Region | North central coast, 5 km (3.1 mi) southeast of Heraklion |

| Coordinates | 35°17′52.66″N 25°9′47.36″E |

| Type | Palace complex, administrative center, capital of Crete and regions within its jurisdiction |

| Length | North-south length of inhabited area is 5 km (3.1 mi)[1] |

| Width | East-west width of inhabited area is 3 km (1.9 mi) max. |

| Area | Total inhabited area is 10 km2 (3.9 sq mi). The palace building itself is 14,000 m2 (150,000 sq ft)[2] |

| History | |

| Builder | Unknown |

| Material | Ashlar blocks of limestone or gypsum, wood, mud-brick, rubble for fill, plaster |

| Founded | The first settlement dates to about 7000 BC. The first palace dates to 1900 BC. |

| Abandoned | At some time in Late Minoan IIIC, 1380–1100 BC |

| Periods | Neolithic to Late Bronze Age. The first palace was built in the Middle Minoan IA period. |

| Cultures | Minoan, Mycenaean |

| Associated with | In the Middle Minoan, people of unknown ethnicity termed Minoans; in the Late Minoan, by Mycenaean Greeks |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1900–1931 1957–1960 1969–1970 |

| Archaeologists | For the initial teams's work discovering the palace: Arthur Evans; David George Hogarth, Director of the British School of Archaeology at Athens; Duncan Mackenzie, superintendent of excavation; Theodore Fyfe, Architect; Christian Doll, Architect For the additional work on the Neolithic starting in 1957: John Davies Evans |

| Condition | Restored and maintained for visitation. Evans used mainly concrete. Modern interventions include open roofing of fragile areas, stabilized soil, paved walkways, non-slip wooden ramps, trash receptacles, perimeter barbed wire fence, security lighting, retail store and dining room[3] |

| Ownership | Originally owned by Cretans, then by Arthur Evans, followed by the British School at Athens, and finally by the current owner, the Hellenic Republic. |

| Management | 23rd Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | "Knossos". British School at Athens. Archived from the original on 2012-05-24. "Knossos". Odysseus. Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-06-17. |

| Current activity is preservational. Restoration is extensive. Painted concrete was used for wood in the pillars. The frescoes often were recreated from a few flakes of painted plaster. | |

Quite apart from its value as the center of the ancient Minoan civilization, Knossos has a place in modern history as well. It witnessed the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the enosis, or "unification," of Crete with Greece. It has been a center of Aegean art and archaeology even before its initial excavation. Currently a branch of the British School at Athens is located on its grounds. The mansion Evans had built on its grounds, Villa Ariadne, for the use of the archaeologists, was briefly the home of the Greek government in exile during the Battle of Crete in World War II. Subsequently, it was the headquarters for three years of the Nazi Germany's military governorship of Crete. Turned over to the Greek government in the 1950s, it has been maintained and improved as a major site of antiquities. Studies conducted there are ongoing.

Excavation by Minos Kalokairinos

The ruins at Knossos were discovered in either 1877 or 1878 by Minos Kalokairinos, a Cretan merchant and antiquarian. There are basically two accounts of the tale, one deriving from a letter written by Heinrich Schliemann in 1889, to the effect that in 1877 the "Spanish Consul," Minos K., excavated "in five places." Schliemann's observations were made in 1886, when he visited the site with the intent of purchasing it for further excavation. At that time, several years after the event, Kalokairinos related to him what he could remember of the excavations.[4] This is the version adopted by Ventris and Chadwick for Documents in Mycenaean Greek. By "Spanish Consul" Heinrich must have meant a position similar to that held by Kalokairinos' brother, Lysimachos, who was the "English Consul." Neither was a consul in today's sense. Lysimachos was the Ottoman dragoman appointed by the pasha to facilitate affairs conducted by the English in Crete.

In the second version, in December 1878 Kalokairinos conducted the first excavations at Kephala Hill, which brought to light part of the storage magazines in the west wing and a section of the west facade. From his 12 trial trenches covering an area of 55 m (180 ft) by 40 m (130 ft) he removed numbers of large-sized pithoi, still containing food substances. He saw the double-axe, sign of royal authority, carved in the stone of the massive walls. In February 1879, the Cretan parliament, fearing the Ottoman Empire would remove any artefacts excavated, stopped the excavation.[5] This version is based on the 1881 letters of William James Stillman, former consul for the United States in Crete, and coincidentally a good friend of Arthur Evans from their years as correspondents in the Balkans. He tried to intervene in the closing of the excavation, but failed. He applied for a firman to excavate himself, but none were being granted to foreigners. They were all viewed as aligning themselves with insurrection, which was true.[6] Evans and Stillman had been whole-heartedly anti-Ottoman, along with most other British and American citizens.

The question could easily have been settled if some ad hoc record of the excavation had survived. Kalokairinos did make a careful record, but during the renewed Cretan insurrection in 1898, his house in Heraklion was destroyed with all the pithoi and his excavation notes. His diaries survived, but they were not very specific. According to Stillman, the "trial trenches" were not exactly that, but were numbers of irregular pits and tunnels. Only the major ones were even recorded. The question of what was at the site before he began work is of less relevance. Arthur Evans' subsequent excavations removed all trace of it and of Kalokairinos' pits.

Waiting for the march of history

After Kalokairinos, several noted archaeologists attempted to preempt the site by applying for a firman, but none was granted by the then precarious Ottoman administration in Crete. Arthur Evans, Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, noted antiquarian and scion of the wealthy Evans family, arrived in Herakleion for the first time in February 1894, mending from his grief at the death of his beloved wife, Margaret, nearly one year previously. Just before her death he had purchased some signet stones engraved in a strange script, which, he was told, were from Crete. During his mourning period Federico Halbherr and Stillman had kept him posted on developments in Crete. It was there that his renewed interest focused. He could not find Halbherr, who had gone to Khania. He purchased more sealstones and an engraved gold ring from Ioannis Mitsotakis, dragoman for Russia (English "Russian vice-consul," but he was a native, not a Russian). After meeting Kalokairinos and inspecting his collection, he set out for Knossos. There he immediately jumped into a trench to examine the signs of the double-axe. The next day he met Halbherr.[7]

The two made a brief tour of Crete. Based on the script he was finding everywhere, which matched that of the stones he had purchased in Athens and the marks on the walls at Knossos, Evans made up his mind. He would excavate, but he had not a moment to lose. He solved the funds obstacle by creating The Cretan Exploration Fund in imitation of the Palestine Exploration Fund, removing the funding from any particular individual, at least in theory initially. The only contributors at first were the Evans'. He secured the services of the local Ottoman administration in purchasing 1/4 of the hill with the first option of buying the whole hill later. They would accept a down payment of £235. Then he went home to wind up his affairs at Youlbury and the Ashmolean. When he returned in 1895 he brought in David George Hogarth, director of the British School at Athens. The two pressed successfully for the purchase of the entire hill and valley adjoining it, obtaining more money through contributions. The owners would accept future payments on the installment plan. Evans selected the site for his future quarters in 1896. They still could not obtain the firman. There was nothing to do but wait for history, which by then was looming on the horizon.[8] After an exploration of Lasithi, or eastern Crete (coincidentally the Muslim half), with John Myres in 1895, the two returned to London in 1896 to write about the Bronze Age forts they had discovered there, under the very shadow of looming civil war.

Crete changes hands

Crete had never belonged to independent Greece, a cause of insurrection and continual conflict between Muslim (previously converted Greek, Turkish and Arab) and Christian (primarily Greek) populations. Of a population of about 270,000, 70,000 were Muslim. In 1897 the conflict in the chronic civil war reached a new crisis. Macedonian Christians, preparing their own insurrection, began sending arms surreptitiously to Crete. The Great Powers were for a blockade, but Britain vetoed it. In 1897, George I of Greece sent Greek troops to the island to protect the Greeks.

The Sultan appealed to the Great Powers, a coalition of European nations that had taken an interest in the Greek revolution. When the Moslems destroyed the Christian quarter of Khania, the capital of Crete, a city of 23,000, British and French marines secured the city, setting up a neutral zone. Shortly after, they secured other cities in the same way. King George sent a fleet containing an occupation force under Prince George. He was warned that a blockade of Athens might ensue, but he sent a reply refusing all measures of the powers, stating that he would not "abandon the Cretan people," and subsequently attacking Khania with the Cretan Christians. The attacking force was driven off with naval gunfire. The Greek army was given six days to leave the island, which they did. The Ottoman army was then ordered to concentrate in "fortified places which are at present occupied by the European detachments" so that they could be guarded and kept in protective custody. For the time being all parties complied. Greece and Turkey, however, resolved the Balkans issue in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, an Ottoman victory. The Great Powers: England, France, Italy, and Russia, however, did not allow the Ottomans to exploit their victory in the Cretan conflict. Crete would remain in the Ottoman Empire, but it would be governed autonomously under their protectorate. A new Constitution was drawn up.[9]

On Crete the Moslems rioted in Candia. In addition to native Christians, 17 British nationals and Lysimachos Kalokairinos were slaughtered. The excavation journal from Knossos was lost. Coalition troops moved swiftly. Turkish troops were ferried off the island by the British fleet. The forces of the Great Powers summarily executed anyone they caught participating in the conflict. The death rate was highest in 1897. While Evans was exploring in Libya, from which he was expelled by the Ottomans, Hogarth returned to Crete, reporting that, from the ship in which he was returning, he saw a village burn and battle raging on the hillside. Prince George of Greece and Denmark was now appointed high commissioner of the protectorate. Evans came back on the scene in 1898, again the foreign correspondent of the Manchester Guardian. He was instrumental and tireless in trying to bring about the rule of reason in Crete, taking the side of the oppressed Moslems finally, as did Hogarth. He ended by assisting the relief effort to stricken villages.[10]

The Cretan Republic was born in 1899 when a combined Christian and Muslim government was elected in accordance with the new constitution. It lasted until 1913. For the time being Evans was not needed in politics. As a firman was no longer necessary, he turned his full attention to the excavation of Knosses, eager to push ahead with it before some other event should remove it from him.

Excavation, 1900–1905

The major excavations at Knossos were performed 1900–1905, at the end of which the wealthy Evans was insolvent. Much later, when he inherited his father's considerable estate, his wealth would be restored, and then some, but in 1905 he had to cancel the excavation of 1906 and return to England to find ways to generate income from Youlbury. The palace, however, had been uncovered, and Evans' concepts of Minoan civilization were known extensively to the public. The term 'palace' may be misleading: in modern English, it usually refers to an elegant building used to house a high-ranking individual, such as a head of state. Knossos was an intricate conglomeration of over 1,000 interlocking rooms, some of which served as artisans' workrooms and food-processing centers (e.g. wine presses). It served as a central storage point, and a religious and administrative center, as well as a factory. No doubt a monarch did reside there, but so also did the better part of his administration. In the age of Linear B, the "palaces" came to be thought of as administrative centers.

The initial team

After the liberation of Crete in 1898, an Ottoman firman was no longer required to excavate, but the permission was in some respects just as difficult to obtain. Before the new Constitution went into effect, the French School of Archaeology under Théophile Homolle was under the impression that it had the right to excavate, based on a previous claim of André Joubin. He soon discovered the Cretan Exploration Fund's ownership. A dispute ensued. David George Hogarth, now Director of the British School at Athens, backed Evans. Evans appealed to the High Commissioner.

In view of Evans' activity on behalf of the cause of Cretan freedom, the Prince decided in his favor, provided he finished paying for the site. This decision was subsequently reaffirmed by the new Cretan government. They knew they could count on Evans to support the subsequent movement for enosis, or union with Greece. By now the price for the rest of the site had diminished. The Cretan Exploration Fund, thanks to additional contributions, purchased it for £200. Prince George was patron of the fund, Evans and Hogarth directors, and Myres secretary. They raised £510, just enough to begin excavation.[11]

Evans' first step after paying for the estate was to restore the former Turkish owner's house as a storeroom, but as it turned out, the repairs were incomplete. A leaking roof was to cause irreplaceable losses of the initial tablets. He and Hogarth lived in Heraklion. After they disagreed on the management of the future excavation, Hogarth suggested that Duncan Mackenzie, who had become notorious after his excavations on the island of Melos, be employed as superintendent. Mackenzie had excavated Phylakopi expertly, 1896–1899, but escaped with the excavation notes, leaving large, unpaid bills, ostensibly to do independent research. Evans cabled him in Rome. He arrived in a week. He was to prove a site superintendent of great capability, but always under Evans' management. Unlike Evans' imaginative guesses, his accounts were sparse and prosaic. Evans also hired, at Hogarth's recommendation, an architect at the beginning of his career, then at the British School at Athens, David Theodore Fyfe. For a foreman Hogarth gave him his own foreman, Gregorios Antoniou, informally Gregóri, a "grave robber and looter of antiquities," who, trusted in a responsible post, proved fanatically loyal.[12] Having helped to get Evans started, Hogarth gracefully departed to excavate the cave at Lasithi, Crete.

The first season

The start of the excavation was a gala event. On March 23, 1900, Evans, Hogarth, Fyfe, and Alvisos Pappalexakis, a second foreman, staged a donkey parade from Heraklion to Kephala Hill. A crowd of persons hoping to be hired had gathered before dawn, some coming from great distances. The archaeologists pitched a tent. Evans ran up the Union Jack. Evans used his cane, called Prodger, to divine a spot to dig for water. The Cretans openly sneered. By chance the diggers broke into an old well, from which water began to gush, establishing Evans as man of supernatural power from that moment on. They hired 31 men, Christians and Muslims. Mackenzie arrived in the afternoon to start a day book of excavation notes.

A few days later, beginning to clear Kalokairinos' pits, they found a stirrup jar, and then a clay tablet, covered with script. Evans hired 79 more men, and purchased iron wheelbarrows. More tablets turned up on April 5. With luck subsequently paralleled by that of Carl Blegen, who discovered the archive room at Pylos on the first day's dig, the excavators uncovered the Throne Room, and in it, a large cache of tablets surrounded by the remains of a box in a terra cotta piece that had once been a bathtub. Evans named the chair found in the room, "the Throne of Ariadne," and the room itself, "Ariadne's Bath." The discovery of the tablets at such an early stage was as unlucky as it was lucky. Evans and Mackenzie had not yet formulated the stratigraphy of the site, and therefore did not record the layers in which the tablets were found. Later reconstruction was to be a judgement, providing a basis for disagreement between Evans and Mackenzie, and controversy over the dates of the tablets.[13]

The tablets soon gave evidence that they were highly friable, but in addition to them, flakes of fresco plaster were beginning to be visible. Realising that he could not trust these fragile artefacts to the unskilled diggers, Evans hired Ioannis Papadakis, a Byzantine fresco restorer, to supervise the delicate excavation. Papadakis used a plaster encasement technique, but even so many tablets were lost. Meanwhile, John Evans had read of the excavation in the London Times. He provided the immediate funds for hiring 98 additional workers, as well as more expertise on the growing number of fresco fragments, Heinrich Schliemann's old draftsman and artist, Émile Victor Gilliéron and his son Émile.

The two artists performed the same services for Evans as they had for Schliemann, reconstruction of full fresco scenes from nothing but flakes. Some of these were very imaginative.[14] There was no deceit of Evans; he knew the method, and approved and paid for the result. Similarly, there was no deceit of the public. Evans and his team were aiming at restoration and reconstruction right from the beginning, rather than pure analysis and preservation. They differed from Mackenzie in this regard. The fact that both Gilliérons were implicated later in life in the manufacture and sale of fraudulent Minoan artefacts is irrelevant; in the early excavation, no one knew what a Minoan object was. They created the concept. Nor can it justly be said that Evans was taken in by them or that the public was deceived by them. It is true that some scenes are mainly guesswork. Others are not.

The first season lasted only nine weeks. Evans' last journal entry for that year (1900) was on May 21. At that time he hired 150 more diggers for a final effort. He also reports a personal episode of malaria. Mackenzie's last entry was May 26, which must have been the last day of the dig for that year, perhaps the most productive of the entire excavation, if judged by progress made. In the few days subsequent, Evans, MacKenzie and Fyfe turned their attention to analysis of the results. Evans wrote reports. Fyfe completed a ground plan. MacKenzie was assigned the classification of pottery. The stratigraphy therefore is most likely mainly his; however, that circumstance does not necessarily validate his memory of the layers in which the tablets were found over Evans'. After a week Evans returned to his home in Youlbury.[15]

The second season

The second season[16] began in February 1901. The three archaeologists were eager to make more progress. By then Mackenzie had formulated the basic stratigraphy. Earliest was a "Kamarais Palace" phase, beginning at about 1800 BC, in parallel with the Kamarais Palace uncovered by Halbherr at Phaistos. Halbherr had dated it to the time of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom based on archaeological similarities. It was followed by a "Mycenaean Palace" phase, beginning at 1550, and a "decline" starting at 1400. Evans turned these into Early, Middle and Late Minoan.

Some severe difficulties appeared in the second season, forcing a decision that split archaeological practice, but as far as Knossos was concerned, Evans and his team had no choice. The severe winter rains had destroyed much of the exposed site through dissolving the mud-brick structures, attacking the alabaster, which was easily dissolved, and washing away many of the features. If the archaeologists did not act to protect the dig, it would melt away even as they excavated. Elsewhere on Crete Hogarth had already encountered the vanishing excavation, washed away by flooding. The team decided to restore, a practice opposed by some archaeologists; that is, as they excavated, they would intervene in the structures to preserve them in situ. Evans noted that nothing out of character with the findings must be introduced. Reconstructed features must be based on other evidence discovered at the site. But of course, the reconstruction was not the original.

Evans began with the columns, wooden structural supports that had more or less disappeared from the delicate structures. He took the shapes from the now restored frescos of the Throne Room. He reinforced or reconstructed walls with concrete. Wooden beams were replaced where evidence indicated there had been one. The Grand Staircase was an especially delicate reconstruction. The excavators could not simply expose the staircase; the walls would collapse. He hired two silver miners from Athens to tunnel down the staircase so that he could prop up the walls and ceilings. Utilizing Fyfe's expertise, he reconstructed fallen second stories and their supporting beams and columns. The palace as it appears today is neither as it was originally nor as it was when excavated. It is a facsimile of the original based on evidence found in the excavation. Evans has been criticised for the decision to restore, but it was either that or nothing. The excavation would have reverted to hillside long since. The criteria as to how much of the design is Evans' or Fyfe's and how much is quasi-original are still in the ephemeral clues from the excavation as recorded mainly by MacKenzie and Evans. The palace cannot justly be discounted as Evan's vision of the past, nor yet can it be accepted as a true remembrance. Evans also used the palace at Phaistos as a template for similar architectural features.

Restoration was an expensive operation. Evans did not stint the expenses he felt were required, even against Hogarth's advice. Hogarth accused him of not understanding thrift because he was a rich man's son. There were but few contributions to the Cretan Exploration Fund. The rich man himself, John Evans, showed up on the back of a donkey that year, his 77th. He had just ridden the donkey extensively over the mountains of Crete in his own exploration of the area, sleeping on boards with a thin mattress. He made major contributions, but he did not cover the cost. Evans insisted the contributions be made to him personally so that no questions of control of the site would be raised. There were scandals that year of workmen pocketing money intended for food, and selling copies of tablets on the black market. The season was cut short in June. The archaeologists were all suffering from malaria, contracted from mosquitos hatched in the standing pools left from the severe winter rains.

Back in Britain that year, Evans encountered the first criticisms of his interpretation of the site. William Ridgeway at Cambridge proposed that the Mycenaeans influenced the Minoans rather than vice versa. Evans called this point of view "Ridgewayism." It did not stand the test of time. There is no evidence of Greeks in the Mediterranean in 1800, but ample evidence of Cretan influence at various locations later Greek. A second line of attack, formulated by W.H.D. Rouse at Cambridge, proclaimed the etymologic impossibility of deriving labyrinth from labrys, and denied any association of mazes and axes. He proposed a derivation of labyrinth from the name of an Egyptian king instead, attempting to "pull rank" on Evans as a scholar, referring to his views as "childish." The Egyptian derivation was never generally accepted. The discovery of the "Mistress of the Labyrinth" in Linear B after Evans' death made Rouse's view less likely. There was evidently a labyrinth at Knossos, of unstated nature, but of religious context, and no one could deny the ample presence of the double-axe symbol.

The third season

The third season, February through June 1902,[17] was intended to be the last, but there was too much work to do to stop then. Evans put 250 diggers to work. In February a cache of fallen fresco fragments came to light, including those of the Queen's Megaron. From them he defined the "Knossian School" of fresco painters. Evans propped up more walls, discovered the sanitation system with the first flush toilet, and uncovered a cache of objects in precious materials, such as the ivory figurines. The work seemed to be nearly done. He anticipated a short season to finish up in the next year.

The fourth season

The 1903 season was expected to be short; the major work was considered done.[18] Evans and Mackenzie stopped keeping detailed notes, making periodic summary journal entries instead. Halvor Bagge was hired to make drawings. However, discovery of the Theatral Area indicated that more work than suspected remained. The season's 50 men were supplemented by another 150 to excavate it.

Toward the end of the season Evans discovered the snake goddess and other valuable portables that might easily be stolen and smuggled. The question came before the Cretan government as to whether members of the excavation, notably Evans, could remove objects from Crete. Evans was anxious to build up a collection in the Ashmolean Museum of which he was Keeper. The answer was resoundingly no. All the artefacts were removed to a temporary museum set up in some old Turkish barracks. There they were guarded by Cretan soldiers. Apparently, however, Evans managed to slip away a few artefacts. He was the least trusted by the Cretan government. The British consul advised Evans that a contribution of artefacts to the museum in Candia might assist his petition to remove artefacts from the country. However, Evans did not follow the advice. He was allowed to take out plaster casts and some pottery fragments.

The fifth season

In the 1904 season Evans expanded operations geographically, discovering the Royal Tomb. His haste and his concentration on Minoan times caused him to sweep away Greek and Roman antiquities on the periphery of the palace as "of no importance," unthinkingly committing what would be in today's high technology milieu, which analyzes pollen and fragments in dust where no antiquities appear to be, a major error. He and the other archaeologists were not only exhausted but were suffering chronically from malarial fevers, not the best circumstances for good judgement, but they were also the only hope of the antiquities being preserved. In addition, the political situation in Heraklion was deteriorating rapidly. They pushed on.

Under the stress Mackenzie was stricken by a complication: growing alcoholism. This condition is attested by Arthur Weigall, an egyptologist, who associated with, and conversed extensively with, Mackenzie on the latter's visit to Saqqara, 1904. Weigall, noting Duncan's disposition to drink whiskey more freely than others, on questioning MacKenzie about it, was told of Mackenzie's custom, at the end of a long, hard day, to down four shots and gallop home to Candia on a horse he named Hellfire.[19]

This testimony is critical as an indirect character reference to Evans. A decade after his death Carl Blegen and others were to make charges that Evans persecuted Mackenzie to cover up errors concerning the date of the Knossos tablets. No record was made of the stratigraphy of the tablets at the time of their discovery, because no stratigraphy yet existed. Mackenzie and Evans disagreed on what they could remember. Later Mackenzie was fired for being drunk on the job. Mackenzie's family denied that Mackenzie was a drinker at all. Evans was accused of malicious persecution of Mackenzie because of the disagreement. Mackenzie could not find work, Blegen and others asserted, because Evans' Old Harrovian network blacklisted him, not because he was an alcoholic or could not be trusted with excavation funds. In fact neither man had any idea of the importance the stratigraphy of the tablets would assume. They simply disagreed on the memory, as they had on many topics. According to Weigall, Mackenzie had a drinking problem as early as 1904. Malicious persecution is not in character with Evans, who always took the side of the underdog, was a thorn in the side to the British military in Crete, performed compassionate works, and was generally troublesome to British intelligence, namely Hogarth, who was paid British agent, although perhaps not in that capacity at Knossos. And finally, Evans' glowing tribute to Mackenzie in his chief work, Palace of Minos, is not in character with a malicious disposition. Like his wife, Evans was popular generally as a sweet and compassionate man, forgiving of sins and willing to think the best of people. He lost his temper, apparently frequently, but was never vindictive, which endeared him to one and all.

The sixth season

The 6th campaign of 1905 was not much of a campaign as far as the hiring of diggers is concerned. The main excavation was over. This season was the last of the initial series. Political troubles had resurfaced in Crete. The Therisos Rebellion pitted a faction of the Cretan Assembly that had voted for enosis at a special meeting at Therisos against the High Commissioner, Prince George, who declared martial law. The revolt was led by the Prime Minister, Eleftherios Venizelos. The issue was whether Crete would remain an autonomous, nominally Ottoman state under the protectorship of the Great Powers, or was a province of Greece. If democracy were to prevail, enosis must be regarded as having been effected by the vote. Prince George commanded the Cretan Gendarmerie. A mild civil war broke out between it and determined bands of citizens. The garrisons of the Great Powers, all but abandoned, lay quiet. In November both sides agreed to arbitration by an international commission.

Evans, dwelling in Candia next to the garrison there, was not affected. The excavation fell relatively silent. Fyfe went home to further his architectural career. Evans replaced him with Christian Charles Tyler (CCT) Doll, another architect, whom he set to rebuilding the Grand Staircase before it collapsed. The substitute woodwork had now rotted away as well. Doll gave it the form it has today. Over the next few years he dismantled the stairs, replaced the wooden beams with steel ones coated with concrete to look like wood, replaced the wooden columns with plaster-coated stone ones, then reassembled the stairs, a technique that became popular for moving monumental antiquities in later decades. In 1910 two additional gypsum blocks were found to fit spaces in the wall, indicating a fourth story had been present. Doll put them in place, supporting them with reinforced concrete.

Doll finished his work on the Grand Staircase in time for Isadora Duncan's visit to the Palace of Minos in 1910. She was a noted dancer who assumed for a time the pose of dancing in floating Greek-style robes and bare feet. She performed on the Grand Staircase at Knossos, floating up and down the stairs. Subsequently, Evans had a malarial night hallucination, in which he saw the characters of the Grand Procession Fresco, led by the Priest-King, floating up and down the stairs.[20]

The grand debut, 1906–1908

In 1906 Arthur Evans was financially insolvent and deeply in debt. He was selling items from his personal art collection to help pay the cost of restoration. This condition did not dampen his enthusiasm for the site. He knew that he was making a contribution to the history of man, which he effused in his lectures and writings. When he returned to Britain each year, honors never failed to accrue to him, not, however money.

He still had an allowance from his father. He decided to use it to build a residence near Knossos. It was never intended to be modest, nor was it for Evans alone, even though he would own it personally, as he did the site. Doll drew up plans in 1906. They ordered the material, the steel from Britain, struggling with the government of Crete for the licenses to import it. Foreigners by then were no longer popular. The Great Powers were viewed as impeding enosis, which, in fact, they were. They had made an agreement with the Ottoman Empire, which they did not intend to break. Commissioners came to Crete, formulated a set of recommendations to the Great Powers, and left. They were further in the direction of enosis than Prince George, the High Commissioner, wished to go; for example, they provided for the departure of all foreign troops and their replacement with a native Cretan defense force. The Prince resigned as High Commissioner in 1906, to be replaced by Alexandros Zaimis. He did everything in his power to support enosis.

International troops began to withdraw in 1908, starting with the French garrison. The British remained until enosis was an accepted fact in 1913. By then it was clear that the Ottoman Empire was no longer an ally of Britain. Meanwhile, Evans had Doll construct his grand house in 1906 and 1907, with his usual disregard for thrift. The house was at first called Palazzo Evans, but then he changed it to Villa Ariadne in honor of the work done at Knossos. The term, "palazzo," is the key to its style. It was constructed of reinforced concrete, in vogue at the time, faced with limestone. The bedrooms were semi-subterranean for coolness. The villa was two-story, today surrounded by trees, then placed on the open hillside. Evans took an upper room where he could observe the sea. By implication, the sea must have been visible from the upper stories of the ancient palace complex as well. Every possible view had an alcove, and every alcove had a window seat. There were walks through an Edwardian garden planted with Cretan flowering shrubs and perennials. The rooms were placed in no special order, but were joined by long corridors. The villa had a bathroom, unusual for those times. The villa is located behind the Little Palace, an easy walk from the hill of the palace complex, and also within walking distance of Heraklion. Today it is near to being swallowed by the suburbs, except for some open land left around it.

Evans was the star resident when he was present, but he never intended the building as his private retreat. All the archaeologists lived there, MacKenzie and Doll included. All important guests stayed there, such as visiting scholars and archaeologists, and yet, it was not a hotel. Like the Cretan palaces, it served also as an administrative center. Every week the workmen would form a queue in the garden to receive their wages. For staff Evans hired Manolaki Akoumianakis as groundskeeper, and Kostis Chronakis as butler and handyman, with his wife, Maria, as cook and housekeeper. This staff were to become known internationally.[21] Evans's house in town also was fully staffed with servants.

In June 1907, after the departure of Evans's friend and supporter, the Prince, Minos Kalokairinos sued Evans on the grounds that the latter had taken a field of his without payment, had excavated without permission, and had illegally removed antiquities found there from the country. The charges as made were undoubtedly true. Evans had excavated a grave there. The antiquities were in the Ashmolean. Kalokairinos was now a lawyer, having attended the university of Athens. The Prince was no longer able to facilitate civil matters for Evans. Ultimately the case was dismissed, due to the death of Kalokairinos by natural causes. He had continued to be interested in local antiquities, publishing an archaeological newsletter, which never mentioned the British excavations.

Evans responded to the increasing unrest and isolation from the Cretans by associating all the more with the British. Until the palazzo was done, he continued to live next to the British garrison in Heraklion. He was a regular guest at the officer's mess there. When not at the garrison, he was hosting dinners for the officers in his own house. The Palace of Minos was now open to a select public. Evans held tea parties in the Throne Room and the Hall of the Double Axes, both subsequently rebuilt. On pleasant days officers and their wives strolled from the garrison to the palace, where they were shown around by whoever happened to be there. Scholarly visitors from all over Europe and the Mediterranean visited often. It became part of the new social life that developed around the last British military outpost in Crete.[22]

In May 1908, Evans's run of tragedies culminated with the death of his father. He inherited a considerable part of the Evans fortune, however. In October by coincidence he inherited the Dickinson fortune from his mother's side. Financial problems at Knossos were over for the time being; however, the place has always been expensive to maintain for whoever owned it. The excavation was in the main done. It remained to Evans to publish it. Having the time and the means, he produced documentation that remains a standard in the field, even today, a privilege not available to most archaeologists.

Knossos in the First World War

As soon as war broke out in 1914, Arthur Evans stopped all work and returned home, to work on Palace of Minos and other documentation for the previous excavations, as well as to formulate future plans. During the war Crete was not on the front lines, but archaeological work did not resume until 1922.

Reconstitution of the palace, 1922–1930

The archaeologists did not return to Knossos until 1922, when the question of Ottoman influence had been settled once and for all (more or less) by the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the defeat of Greek and British forces occupying Turkey after the First World War, and treaties that established the borders of the Republic of Turkey under Mustafa Kemal, founder and first Prime Minister. By then the wood used in the reconstruction work done before 1913 was rotten and many parts of the palace were on the verge of collapse. Evans thus decided to "reconstitute" the palace using reinforced concrete.

To oversee reconstruction, Evans hired Piet de Jong, an English artist and architect who had previously worked both as an archaeological illustrator and in the Greek Reconstruction Service after World War One. Reconstruction work began with the Stepped Portico. In 1926, Fyfe returned for a month to rebuild the South Propylaeum.

Evans's reconstructions are controversial. They included reconstructions of features not attested in the archaeological record, such as ceilings, stairways, and upper stories. Moreover, his choice of concrete made his work irreversible, meaning that his reconstructions cannot be corrected as new evidence comes to light.

In 1926, Evans donated the palace, the grounds, and Villa Ariadne to the British School at Athens. In essence the school was to take over the excavation and operate it as a means of training students, though transfer had no immediate effect on the direction or the living arrangements. Rather, the decision was a financial one for Evans, who was struggling to pay for upkeep and improvement of the site. The Greek and British governments approved the transfer, waiving taxes.[23]

In 1929, Evans fired his assistant, Duncan MacKenzie. Despite his previous invaluable contributions, MacKenzie had grown unreliable due to chronic illness including alcoholism, depression, and malaria. Evans planned to retire him at the end of the year, but an incident of drunkenness on the job caused Evans to move the date up to June of that year. MacKenzie was unable to find another position in archaeology, and died in an institution for the mentally ill in 1934.

Interwar Knossos

Evans replaced Mackenzie with John Pendlebury, a 25-year-old archaeologist just getting a start through the British School of Archaeology at Athens. Pendlebury had many qualities remarked by his contemporaries. He was an outstanding athlete, swimming often and running wherever he went to work or for adventure, exceeded in this regard only by some of his female graduate students. He walked all over Crete in his first year. He spoke fluent Cretan, sang the native songs, danced the native dances, and was the accepted natural leader wherever he went. He wore a glass eye and delighted in carrying a sword-cane, which parallels to Evans's short-sightedness and cane, Prodger, may well have been influential in the development of a rapport. He was joined by his wife, Hilda, in 1930. He and Evans conducted the last excavation in the palace, the Temple Tomb.

Subsequently, Evans went home, leaving the site in Pendlebury's able hands. He would return rarely before 1935, when he was at hand for the dedication of his memorial, and received an honorary citizenship of Heraklion. Then he returned no more. Pendlebury was by no means alone. He was the leader of a "new generation" at Knossos.[24] Humfry Payne was the Director of the British School at age 28. He was assisted by Dilys Powell, his wife. Together with Pendlebury they brought in a set of graduate students of exceptional talent, who could be sent over Crete and Greece and trusted to conduct excavations. Among them were five women. Many would not get many years older, and all would be tested to the utmost of their ability. Ignored in World War I, Knossos was at the center of Mediterranean operations in World War II.

Now that the excavation was finally over, Evans was concerned with organizing and dating material that had been placed in the Stratigraphical Museum, which he had kept from the beginning. It consisted of thousands of shards of pottery, which had to be organized and dated. Pendlebury inherited this task. He had the assistance of his wife, Hilda, and of Manoli Akoumianos, a foreman under Evans, now an archaeologist.

In addition they were joined by Mercy Money-Coutts, Lord Latymer's only daughter. She had a degree in modern history, and later became expert in Minoan pottery.[25][26] She also spoke French from childhood, was an artist, a good horsewoman and an expert marksman. She enjoyed hunting foxes and stalking deer. She was the only graduate student who could outrun Pendlebury.[24]

Museum work was not John Pendlebury's preference. Even while working at Knossos, he developed commitments to the Egyptian Exploration Society, assuming directorship of the excavation at Amarna on an occasional basis. Resigning as Knossos Curator in 1934, he excavated Lasithi, Crete, 1936–1939, with Hilda and Mercy. Like Evans, Pendlebury did not ask for character references. His diggers included two murderers, a sheep-stealer and a leper. Meanwhile, Evans replaced him with Richard W. Hutchinson, who was Knossos Curator in absentia during the three-year occupation of Crete by the Germany. Both Pendlebury and Hutchinson wrote works that, next to Evans's Palace of Minos, have become standard on the archaeology of Crete.

In 1938 the British War Office interviewed the Knossos archaeologists for possible service in MI(R), Military Intelligence (Research), which was incorporated into Special Operations Executive (SOE) in 1940. They were interested in recruiting persons with special knowledge and languages of the Mediterranean area in case war should break out. The archaeologists were to wait to be contacted. After war broke out in 1939 most British citizens abroad returned home to volunteer their services in any capacity. The urgency was less in Crete because, at least for some months, Greece remained neutral. In 1939 archaeological operations everywhere in Crete were closing. The archaeologists there also were returning to Britain. Among them was Pendlebury, who, despairing of MI(R), enlisted in a cavalry regiment. In 1940, in the shadow of the invasion of Greece, MI(R) contacted Pendlebury. He was given a course in explosives. His assignment was travel to Crete, contact the Cretans he had known, and organize bands of partisans. He was the only British citizen to be allowed into Crete by the Greek government. The other recruits went on to Cairo, where they were given various assignments. As a cover Pendlebury, posing as a cavalry officer, was made a military attaché, a Vice Consul, at Heraklion, in charge of liaison between the Greek and British militaries. At the time there were no significant British forces in Crete, but this cover gave him an excuse to be in the countryside.[27]

Knossos in the Second World War

After the Battle of Crete, the area was occupied by Nazi Germany. After the Germans left in 1944, Evans's Villa Ariadne became the headquarters of the British Area Command. The newly founded UNRRA took up residence there and began to bring relief to the Cretans. Relief workers included the archaeologist Mercy Seiradaki who had previously worked with Evans at the site. The German surrender in 1945 was signed at Villa Ariadne.[24]

Post-war Knossos

In 1945, Hutchinson resumed the curatorship of Knossos, which was passed to Piet de Jong in 1947, and then to the Greek Archaeological Service in 1951. Since then, the area around the site has urbanized with growth of Heraklion, and the site itself has become a major tourist attraction. In 1966 Sinclair Hood built a new Stratigraphical Museum.

See also

References

- Papadopoulos, John K (1997), "Knossos", in Delatorre, Marta (ed.), The conservation of archaeological sites in the Mediterranean region : an international conference organized by the Getty Conservation Institute and the Paul Getty Museum, 6–12 May 1995, Los Angeles: The Paul Getty Trust, p. 93

- McEnroe, John C. (2010). Architecture of Minoan Crete: Constructing Identity in the Aegean Bronze Age. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 50. However, Davaras & Doumas 1957, p. 5, an official guide book in use in past years, gives the dimensions of the palace as 150 m (490 ft) square, about 20,000 m2 (220,000 sq ft). A certain amount of subjectivity is undoubtedly involved in setting the borders for measurement.

- Stratis, James C. (October 2005), Kommos Archaeological Site Conservation Report (PDF), kommosconservancy.org

- Driessen 1990, p. 24.

- Castleden 1990, p. 22.

- Begg 2004, pp. 8–9.

- MacGillivray 2000, pp. 115–124.

- Gere 2009, pp. 64–65.

- The above summary is based on Johnston, Albert Sidney; Clarence A Bickford; William W. Hudson; Nathan Haskell Dole (1897). "The Eastern Crisis". The Cyclopedic Review of Current History. 7 (2): 17–46.

- MacGillivray 2000, pp. 154–162

- MacGillivray 2000, pp. 163–168.

- MacGillivray 2000, pp. 170–173.

- The events of the early excavation are stated by MacGillivray 2000, pp. 174–191.

- Gere 2009, p. 111. "Some of the most popular images of Minoan life, such as the 'Ladies in Blue' fresco are almost complete inventions of these twentieth-century artists."

- MacGillivray 2000, pp. 190–191.

- MacGillivray 2000, pp. 202–216.

- MacGillivray 2000, pp. 216–221.

- MacGillivray 2000, pp. 221–226.

- MacGillivray 2000, pp. 227–230.

- MacGillivray 2000, pp. 231–233

- MacGillivray 2000, pp. 236–241.

- Brown 1983, pp. 30–31.

- MacGillivray 2000, pp. 290–294

- Schofield, Elizabeth, "Mercy Money-Coutts Seiradaki (1910-1993)", Breaking Ground: Women in Old World Archaeology (PDF), Brown University

- 'University News', The Times 30 July 1932, p12

- Elizabeth Schofield, Mercy Money-Coutts Seiradaki (1910-1993)

- Beevor, Antony (1994). Crete: the battle and the resistance. Boulder: Westview Press. pp. 3–5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Bibliography

- Begg, D.J. Ian (2004), "An Archaeology of Palatial Mason's Marks on Crete", in Chapin, Ann P (ed.), ΧΑΡΙΣ: Essays in Honor of Sara A. Immerwahr, Hesperia Supplement 33, pp. 1–28

- Benton, Janetta Rebold and Robert DiYanni.Arts and Culture: An introduction to the Humanities, Volume 1 (Prentice Hall. New Jersey, 1998), 64–70.

- Bourbon, F. Lost Civilizations (New York, Barnes and Noble, 1998), 30–35.

- Brown, A. Cynthia (1983). Arthur Evans and the Palace of Minos. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum. ISBN 9780900090929.

- Castleden, Rodney (1990). The Knossos Labyrinth: A New View of the 'Palace of Minos' at Knossos. London; New York: Routledge.

- Davaras, Costos; Doumas, Alexandra (Translator) (1957). Knossos and the Herakleion Museum: Brief Illustrated Archaeological Guide. Athens: Hannibal Publishing House.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - Driessen, Jan (1990). An early destruction in the Mycenaean palace at Knossos: a new interpretation of the excavation field-notes of the south-east area of the west wing. Acta archaeologica Lovaniensia, Monographiae, 2. Leuven: Katholieke Universiteit.

- Gere, Cathy (2009). Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226289540.

- Gundelach, Karl (1965), "The Battle for Crete 1941", in Jacobsen, Hand Adolph; Rohwer, J; Fitzgerald, Edward (Translator) (eds.), Decisive Battles of World War II: the German View (First American ed.), New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, pp. 99–132

{{citation}}:|editor3-first=has generic name (help) - Kiriakopoulos, G C (1995). The Nazi occupation of Crete: 1941 - 1945. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger.

- Landenius Enegren, Hedvig. The People of Knossos: prosopographical studies in the Knossos Linear B archives (Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, 2008) (Boreas. Uppsala studies in ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern civilizations, 30).

- MacGillivray, Joseph Alexander (2000). Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth. New York: Hill and Wang (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). ISBN 9780809030354.

External links

- "Knossos". interkriti. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- "The Battle for Crete". This Happens in War. Remembering Scotland at War. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- "The union of Crete with Greece". Explore Crete. Retrieved 27 May 2012.