Kogal

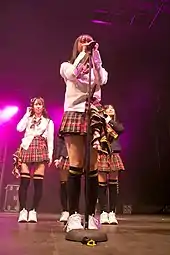

Kogal (コギャル, kogyaru) is a Japanese fashion culture (a type of gyaru fashion[1][2]) that involves girls wearing an outfit based on Japanese school uniforms (or their actual uniforms). The girls may also wear loose socks and scarves, and have dyed hair.[3][4] The word kogal is anglicized from kogyaru, a contraction of kōkōsei gyaru ("high school gal").

Aside from the miniskirt or microskirt, and the loose socks, kogals favor platform boots, makeup, and Burberry check scarves, and accessories considered kawaii or cute on bags and phones.[5] They may also dye their hair brown and get artificial suntans. They have a distinctive slang peppered with English words. They are often, but not necessarily, enrolled students. Centers of kogal culture include the Harajuku and Shibuya districts of Tokyo, in particular Shibuya's 109 Building. Pop singer Namie Amuro promoted the style. Kogals are avid users of photo booths, with most visiting at least once a week, according to non-scientific polls.[6]

Etymology

The word kogal is a contraction of kōkōsei gyaru (高校生ギャル, "high school gal").[7] It originated as a code used by disco bouncers to distinguish adults from minors.[7] The term is not used by the girls it refers to. They call themselves gyaru (ギャル),[8] a Japanese pronunciation of the English word "gal".[7] The term gyaru was first popularized in 1972 by a television ad for a brand of jeans.[9] In the 1980s, a gyaru was a fashionably dressed woman.[9] When written 子, ko means "young woman," so kogyaru is sometimes understood in the sense of "young gal".[10]

Character

Kogals have been accused of conspicuous consumption, living off their parents and enjo-kosai (amateur prostitution/dating service).[11] It is unclear how many girls were actually involved in prostitution.[12] Critics decry their materialism as reflecting a larger psychological or spiritual emptiness in modern Japanese life. Some kogals support their lifestyle with allowances from wealthy parents, living a "parasite single" existence that grates against traditional principles of duty and industry.[13] Though brand-name accessories are part of the kogal look, many kogal may buy these cheaply as knock-off versions of a high-brand item from stalls in back-alley markets like ura Harajuku.[14][15] Some feminists "saw the young women as cleverly negotiating their own position in a male patriarchal world."[16]

Others have charged that the kogal phenomenon is less about the girls and their fashions than a media practice to fetishize school uniforms and blame those required to wear them.[17] "I wish that I were in high school at a different time," said one schoolgirl. "Now, with kogal being such an issue in Japan, nobody can see me for me. They only see me as kogal, like the ones they see on TV."[13] Others state the kogal look was used alongside the enjo kōsai panic of the 1990s. A former editor of egg magazine, a gyaru fashion magazine, said "enjo kōsai began as a mischievous but relatively innocent way of playing pranks on middle-aged men." This included exchanged small amounts of money for dates that lasted a few minutes. It was reported that the media coverage was framed as if all high school girls "were rushing to Shibuya and having sex with men in karaoke boxes just to buy luxury goods." Years later, it was debunked as a stereotype. [18]

The kogal phenomenon has never represented a majority of teenage girls. Rather, it largely symbolizes the evolution of the role of women in capitalist Japan. As such, the kogal style rejects not only tradition which Japan is known for but the spirit of nationalism, seeking to embody stateless consumerism. This consumerism is communicated through knock-off designer goods, trips to photo booths, singing karaoke, partying, the use of love hotels, and incorporating new loanwords into everyday speech. Kogals also take a transactional approach to sexual activity, employing more risque language or referring openly to sex. Kogal hedonism and impolite language serve to assert self-hood of young Japanese women. Kogals' expertise in criticizing men, particularly older men, demonstrates their revolt against traditional gender norms. Kogal publications like Egg's artwork gallery of male anatomy show that kogal culture can also empower young women to express displeasure and value their own pleasure. Overall, kogal language, behavior, and images reflect an urge to usurp an orderly society.[19]

History

Japanese fashion began to divide by age in the 1970s with the appearance of gyaru magazines aimed at teens. Popteen, the most widely read of these magazines, has been publishing monthly since 1980. While mainstream fashion in the 1980s and early 1990s emphasized girlish and cute (kawaii), gyaru publications promoted a sexy aesthetic.[20] Top gyaru magazines, including Popteen, Street Jam and Happie Nuts, were produced by editors previously involved in creating pornography for men.[20]

Also in the 1980s, a male-and-female motorcycle-oriented slacker culture emerged in the form of the "Yankiis" (from the American word "Yankee") and Bosozoku Gals. The original kogals were dropouts from private school who, instead of lengthening their skirts like androgynous Yankii girls, created a new form of teen rebellion by shortening them.[21] These middle school dropouts were thus taking their cues from high school students and attempting to justify their independence by looking and acting older. The gals added their own touches like loose socks and a cellular phone.[22]

The 1993 television special Za kogyaru naito (The Kogal Night) introduced the kogal to a mass audience and provided a model for aspiring kogals to follow.[7] Platform shoes were popularized by singer Namie Amuro in 1994.[23] Egg, a fashion magazine for kogals, was established in 1995.

In the mid-1990s, the Japanese media gave a great deal of attention to the phenomenon of enjo kōsai ("paid dating") supposedly engaged in by bored housewives and high school students, thus linking kogals to prostitutes.[17] The movie Baunsu ko gaurusu (Bounce Ko Gals) (1997) by Masato Harada depicts kogals prostituting themselves to buy trendy fashion accessories.[24][25]

Kogal culture peaked in 1998. Kogals were then displaced by another style that gained popularity through Egg: ganguro, a gal culture that first appeared in the mid-1990s and used dark makeup combined with heavy amounts of tanning.[26] Ganguro evolved into another extreme look (though less extreme than ganguro) called yamanba ("mountain hag"). As looks grew more extreme, fewer girls were attracted to gal culture. Although there are still female students who sexualize their uniforms, the kogal is no longer a focus of fashion or media attention.

Gal fashion later reemerged in the form of the skin-whitening Shiro Gyaru, associated with Popteen.[27] One such example of this is the Onee Gal, who take their fashion cues from Hollywood. Clad in stilettos and jewels, these gals parade the streets of Shibuya. The women opting for this style are often gals of previous generations that are returning for this style, which is sexy yet more adult. Unlike their younger counterparts, there is less clubbing and more projecting an image of sky-high social status. Despite this, the Onee Gals are more serious about their lives than other gal groups, with their age placing them in college or the workforce. One of the driving forces behind this is Sifow, a singer and idol that subscribes to the Onee Gal style.[26]

The Hime gyaru (literally "lady gal," also translated as "princess gal"), also part of the Shiro Gyaru style, first appeared in 2007. The girls in this subculture seem to want to live as princesses like out of fairy tales, complete with over-glamorous lifestyles and items. They wear princess-like dresses (usually in pink or other pastels), and sport large, curly brown hair, usually in bouffants. Popular brands for this subsection of Gal include Liz Lisa and Jesus Diamante.[26][27][28][29]

The waves of changing female Japanese beauty culture such as the kogal represent a growing diversity in female beauty which contrasts with the focus on docility and cuteness perpetuated previously. Kogal and its predecessors visually chronicle the evolution of Japan into a consumer culture, visibly displaying the changing values and norms within Japanese culture as consumerism necessitates the displacement of the identity to surface features.[30]

Language

Kogals are identified primarily by looks, but their speech, called kogyarugo (コギャル語), is also distinctive,[7] including, but not restricted to the following: ikemen (イケ面, "Cool dude"), chō-kawaii (超かわいい, "totally cute"),[7] gyaru-yatte (ギャルやって, "do the gal thing"), gyaru-fuku (ギャル服, "gal clothes"), gyaru-kei shoppu (ギャル系ショップ, "gal-style shop"), gyaru-do appu no tame ni (ギャル度アップのために, "increasing her degree of galness"), chō maji de mukatsuku (超マジでむかつく, "really super frustrating").[7] As a way to celebrate their individuality, gals might say biba jibun (ビバ自分, "long live the self", derived from Viva and the Japanese word for "self").[7]

Gals' words are often created by contracting Japanese phrases or by literal translation of an English phrase, i.e. without reordering to follow Japanese syntax.[31] Gal words may also be created by adding the suffix -ingu (from English "-ing") to verbs, for example gettingu (ゲッティング, "getting").[31] Roman script abbreviations are popular, for example "MM" stands for maji de mukatsuku ("really frustrating"). "MK5" stands for maji de kireru go byoumae (マジでキレる5秒前, "on the verge of lit. 'five seconds away from' going ballistic").[31] Another feature of gal speech is the suffix -ra, meaning "like" or "learned from," as in Amura (アムラー, "like singer Namie Amuro").[31]

The English used in kogal speech is often a combination of two or more English words which have taken on new meaning in Japan.[7]

See also

- Gals! – a shōjo manga by Mihona Fujii about kogals

- Gyaru

- My First Girlfriend Is a Gal, a shōnen manga by Meguru Ueno

- Japanese street fashion

- Modern girl

- Preppy

- Uniform fetishism

- Zettai ryōiki

References

- "What Is Kogal Fashion, Gyaru's More Subtle Style Subculture?". Clozette. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- B, Rachel (August 7, 2013). "Gyaru-go". Tofugu. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- Uranaka, Taiga (November 12, 2003). "Man who gave us loose white socks eyes comeback" – via Japan Times Online.

- "Japan's schoolgirls set the trend". Independent.co.uk. November 23, 1997.

- "What Is Kogal Fashion, Gyaru's More Subtle Style Subculture?". Clozette. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- Miller, Laura; Bardsle, Jan. Bad Girls of Japan. p. 130.

- Miller, Laura, "Those Naughty Teenage Girls: Japanese Kogals, Slang, and Media Assessments", Journal of Linguistic Anthropology: Volume 14: Number 2 (2004).

- "» The History of the Gyaru – Part One:: Néojaponisme » Blog Archive". Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- "Shiro Gal (Light Skin Gal) Archived 2009-05-01 at the Wayback Machine"

- "Osaka - Japan"

- author (April 19, 2018). "Kogal Fashion Style: Japanese Youth Subculture | japadventure.com". japadventure.com. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - "» The History of the Gyaru – Part Two:: Néojaponisme » Blog Archive". Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- Sky Whitehead, "K is for Kogal Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine"

- Miller, Laura (2012). "Youth fashion and beautification". In Mathews, Gordon; White, Bruce (eds.). Japan's Changing Generations: Are Young People Creating a New Society?. Routledge. pp. 87–88. ISBN 9781134353897.

- Japanese Schoolgirl Confidential: How Teenage Girls Made a Nation Cool (Tuttle Publishing, 2014), ISBN 9781462914098

- "» The History of the Gyaru – Part Two:: Néojaponisme » Blog Archive". Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- Kinsella, Sharon, "What's Behind the Fetishism of Japanese School Uniforms?", Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture, Volume 6, Number 2, May 2002 , pp. 215-237(23)

- "» The History of the Gyaru – Part Two:: Néojaponisme » Blog Archive". Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- Miller, Laura (2004). "Those naughty teenage girls: Japanese Kogals, slang, and media assessments". Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 14 (2): 225–247. doi:10.1525/jlin.2004.14.2.225.

- Kinsella, Sharon, "Black faces, witches and racism", Bad Girls of Japan, edited by Laura Miller, Jan Bardsley, p. 146.

- "The Misanthropology of Late-Stage Kogal Archived 2007-10-16 at the Wayback Machine"

- Evers, Izumi, Patrick Macias, (2007) Japanese Schoolgirl Inferno: Tokyo Teen Fashion Subculture Handbook, p. 11. ISBN 0-8118-5690-9.

- Miller, Laura, "Youth Fashion and changing beautification practices," Japan's Changing Generations: Are Young People Creating a New Society edited by Gordon Mathews, Bruce White, p. 89.

- Nix, Bounce ko Gal aka Leaving (1997) Movie Review Archived 2009-10-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Bounce KoGALS (1997) Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

- "[Japanese Schoolgirl Inferno: Tokyo Teen Fashion Subculture Handbook]"

- "Gyaru Resurgence". Mekas. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011.

- "Japan's Latest Fashion Has Women Playing Princess for a Day", Wall Street Journal, November 20, 2008.

- "The Gyaru Handbook - Casual hime gyaru style DEBUNKED!". Gal-handbook.livejournal.com. November 19, 2007. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- Miller, Laura (2000). "Media Typifications and Hip Bijin". US - Japan Women's Journal. 19 (19): 176–205. JSTOR 42772168.

- "コギャル語&ギャル語辞典 Archived 2007-12-15 at the Wayback Machine"

Further reading

- Macias, Patrick; Evers, Izumi (2007). Japanese Schoolgirl Inferno - Tokyo Teen Fashion Subculture Handbook. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-8118-5690-4.

- "Those Naughty Teenage Girls: Japanese Kogals, Slang, and Media Assessments", by Laura Miller. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology: Volume 14: Number 2 (2004).

- Ashcraft, Brian; Ueda, Shoko (2014). Japanese schoolgirl confidential : how teenage girls made a nation cool. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462914098.

.jpg.webp)