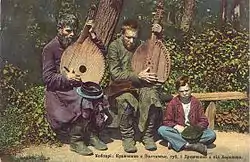

Kobzar

A kobzar (Ukrainian: кобзар, pl. kobzari Ukrainian: кобзарі) was an itinerant Ukrainian bard who sang to his own accompaniment, played on a multistringed bandura or kobza.

Tradition

.jpg.webp)

Kobzars were often blind and became predominantly so by the 1800s. Kobzar literally means 'kobza player', a Ukrainian stringed instrument of the lute family, and more broadly — a performer of the musical material associated with the kobzar tradition.[1][2]

The professional kobzar tradition was established during the Hetmanate Era around the sixteenth century in Ukraine. Kobzars accompanied their singing with a musical instrument known as the kobza, bandura, or lira. Their repertoire primarily consisted of para-liturgical psalms and "kanty", and also included a unique epic form known as dumas.

At the turn of the nineteenth century there were three regional kobzar schools: Chernihiv, Poltava, and Slobozhan, which were differentiated by repertoire and playing style.

Traditional minstrels from this time period also included lirnyky, musicians who played the hurdy-gurdy.[3] While some sources suggest that kobzari were not always blind, lirnyky were likely disabled, and in general to be considered a kobzar or lirnyk, the minstrel was blind.[3] Kobzari and lirnyki were considered the same category of minstrel, belonging to the same guilds and sharing songs.[3]

Guilds

In Ukraine, kobzars organized themselves into regional guilds or brotherhoods, known as tsekhs (tsekhy).[4] They developed a system of rigorous apprenticeships (usually three years in length) before undergoing the first set of open examinations in order to become a kobzar.[5][6] Among the marks of professional competence necessary to gain entry to a guild was mastery of a secret guild language known as the lebiiska mova.[7]

These guilds were thought to have been modelled on the Orthodox Church brotherhoods as each guild was associated with a specific church.[6] These guilds then would take care of one church icon or purchase new religious ornaments for their affiliated church (Kononenko, p. 568–9).[8] The Orthodox Church however was often suspicious of and occasionally even hostile to kobzars.

End of kobzardom

The institution of the kobzardom essentially ended in the Ukrainian SSR in the mid 1930s during Stalin's radical transformation of rural society which included the liquidation of the kobzars of Ukraine.[9][10][11][12] Kobzar performance was replaced with stylized performances of folk and classical music utilising the bandura.

Soviet version

Soviet kobzars were stylised performers on the bandura created to replace the traditional authentic kobzari who had been wiped out in the 1930s. These performers were often blind and although some actually had contact with the authentic kobzari of the previous generation, many received formal training in the Folk conservatories by trained musicians and played on contemporary chromatic concert factory made instruments.

Their repertoire was primarily made up of censored versions of traditional kobzar repertoire and focused on stylized works that praised the Soviet system and Soviet heroes.

Re-establishment of the tradition

In recent times, there has been an interest in reviving of authentic kobzar traditions which is marked by the re-establishing the Kobzar Guild as a centre for the dissemination of historical authentic performance practice.

Other use of the term

Kobzar is a seminal book of poetry by Taras Shevchenko, the great national poet of Ukraine.

The term "kobzar" has on occasion been used for hurdy-gurdy players in Belarus (where the hurdy-gurdy is often referred to as a "kobza", and bagpipe players in Poland where the bagpipe is referred to as a "kobza" or "koza").

References

- Volodymyr Kushpet "Startsivstvo", 500pp, Kyiv "Tempora" 2007

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Susan Ranson, Ben Hutchinson(2008), Rainer Maria Rilke's The book of hours, Camden House. p. 215. ISBN 1-57113-380-1

- Kononenko, Natalie O. (1998). Ukrainian minstrels: and the blind shall sing. Folklores and folk cultures of Eastern Europe. Armonk, N.Y. London: M.E. Sharpe. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7656-0145-2.

- Kononenko, Natalie O. (1998). Ukrainian minstrels: and the blind shall sing. Folklores and folk cultures of Eastern Europe. Armonk, N.Y. London: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 66–85. ISBN 978-0-7656-0145-2.

- Kononenko, Natalie O. (1998). Ukrainian minstrels: and the blind shall sing. Folklores and folk cultures of Eastern Europe. Armonk, N.Y. London: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 86–107. ISBN 978-0-7656-0145-2.

- Kononenko, Natalie O. (1998). Ukrainian minstrels: and the blind shall sing. Folklores and folk cultures of Eastern Europe. Armonk, N.Y. London: M.E. Sharpe. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7656-0145-2.

- Kononenko, Natalie O. (1998). Ukrainian minstrels: and the blind shall sing. Folklores and folk cultures of Eastern Europe. Armonk, N.Y. London: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 72–74. ISBN 978-0-7656-0145-2.

- Kononenko, Natalie O. (1998). Ukrainian minstrels: and the blind shall sing. Folklores and folk cultures of Eastern Europe. Armonk, N.Y. London: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-0-7656-0145-2.

- Grigorenko site Archived 2005-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ‘Remember the peasantry’: A study of genocide, famine, and the Stalinist Holodomor in Soviet Ukraine, 1932-33, as it was remembered by post-war immigrants in Western Australia who experienced it Lesa Melnyczuk Morgan, 2010, University of Notre Dame Australia "During the mid-1930s, the [kobzars] were invited to the First All-Ukrainian Congress of Lirniki and Banduristy (folk singers, minstrels) where they were arrested and, in most cases shot". In the notes: "Although noted by a few different authors there is no mention of where this occurred." Accessed 8 February 2021

- Robert Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow. Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine., p.266. ISBN 0195051807

- Volkov Solomon, ed. Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich (New York: Faber & Faber,1979), pp.214-15. ISBN 978-0060144760

- Kononenko, Natalie O. “The Influence of the Orthodox Church on Ukrainian Dumy.” Slavic Review 50 (1991): 566–75.

External links

- Kobzars at Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- "Kobzar" book by Taras Shevchenko at Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- National Union of the Ukrainian Kobzars official site (in Ukrainian)

- The last kobzar, a portrait of OSTAP KINDRACHUK, a film by Vincent Moon