Kocabaş cranium

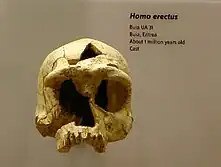

The Kocabaş cranium is the damaged calvarium fossil of a young Homo erectus discovered near the village of Kocabaş, located in the Denizli Province of Turkey by quarry workers in 2002.[1]

| |

| Catalog no. | Kocabaş |

|---|---|

| Common name | Kocabaş cranium |

| Species | Homo erectus |

| Age | 1.3-1.1 mya |

| Place discovered | Denizli Province, Turkey |

| Date discovered | 2002 |

| Discovered by | Quarry workers |

History

The Kocabaş calvarium was discovered in 2002 by quarry workers during a travertine mining operation possibly at Faber Quarry[2] near the Turkish village of Kocabaş. Although it is unknown where exactly the fossil was discovered, initial electron spin resonance dates suggest an age of 1.11±0.11 mya, and thermoluminescence suggests an age of 510±50 to 330±30 ka (later estimates suggesting 1.3-1.1 mya using chronology[3]). Further, the fauna of the site, such as Equus aff. sussenbornensis, may affirm a Lower-Middle Pleistocene date. In 2012, digital reconstruction and rearticulation using software was performed and published. Using the saw slice at the top of the skull and the anatomy of the outer bone and endocast as a guide, the team was able to restore the bone. Upon discovery, the left parietal and frontal being connected was used as a guide to reconstruct the mirrored half. The glabella was unable to be restored. Once complete and mirrored, the specimen demonstrates a more complete degree of preservation and allowed for the taking of measurements.[1]

Description

The specimen was discovered largely before the raw material was cut by saw blades into 35 mm-thick slabs to be commercially distributed, although it was sliced once transversely across the parietal, removing a section of the parietal and upper mid-frontal edge. Of what was recovered, the anterior of both parietals and lateral parts of the frontal were reported. The superior half of the temporal is intact on the left, with both sides being rimmed by temporal lines that are fused to form a marked ridge. Nothing remains of the orbital cavity on the left except for a minimal portion of the lateral orbital roof. The lateral supratoral region on the right is preserved and so is the brow, which is intact until the lateralmost supraorbital notch and the glabella, which is damaged to reveal both ethmoidal cells. Overall, the calvarium is composed of parts 1 (left frontal), 2 (right parietal), and 3 (right frontal). Sutures in the bone are not fully fused, suggesting that the individual was young,[1] possibly late juvenile or young adult in age.[2]

The curvature of the lobes of the brain appears similar to Zhoukoudian, Sangiran, and Dmanisi. Post-orbital constriction in the specimen and the large brow is close to Asian Homo erectus. Unlike specimens with developed brows and Dmanisi, a lateral supratoral depression is evident. This is most similar to Zhoukoudian L-C, OH 9 and KNM ER 3733. It lacks a keel, unlike Chinese specimens, but keeps slight parasagittal depressions. Vascular and cephalic impressions are developed in a manner typical of the species.[1]

Paleopathology

Many strange granular impressions on the endocranial surface of the frontal were described by Kappelman et al. (2008) and suggested that, based on the characters of the lesions, the individual was suffering from Leptomeningitis tuberculosa. Instead, Roberts et al. (2009) offered alternative explanations, such as post-depositional damage, which the original team reported were antemortem damage without proof. Their answer to bone remodeling is ectopic arachnoid granulations with post-depositional damage causing the grows to be sharpened. The original authors postulated that tuberculosis was caused by a lack of vitamin D due to dark-skinned hominins reaching Europe, leaving their immune systems compromised.[4] However, the comment made by Roberts et al. (2009) suggests that this is controversial because there are no signs of deficiency.[5]

Classification

Vialet et al. (2012) posit that the anatomy and measurements of the specimen supports the findings of Grimaud-Hervé et al. 2002 and Baab 2008, being a single long-lived but discontinuous species, Homo erectus.[6] They support the varied single species hypothesis seeing as how Kocabaş is alike to specimens from Georgia and Africa; thus, specimens from Africa and Asia are considered to belong to the single species Homo erectus with considerable variation.[1] Vialet et al. (2018) performed cladistic analysis as a part of their review of the specimen, indicating the it is intermediate of the thin-browed Chinese Homo erectus (Zhoukoudian) and the heavily-browed African Homo erectus (OH 9, Daka). As such, it aligns with the sample at Dmanisi, but remains morphologically distinguished from all parties. They cite the shorter and front-to-back narrower dimensions with a small size and a defined brow as set apart from mid-upper Pleistocene hominins. Their cladistic results:[2]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sts 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The hypothetical ancestor of the clade containing Kocabaş is supported by all sampled specimens having both temporal lines fusing and separating from the parietal as if not to form a developed ridge. It is not related to European hominins of the Middle Pleistocene, namely Arago and Ceprano, which are more basal in their brow. However, portions of the brow in Kocabaş that are damaged cannot be studied to confirm this. The frontal is weakly differentiated from African Homo erectus aged around 1 mya. This individual likely stems from an African lineage not related to the older groups from Asia. Other specimens of similar antiquity and dubious taxonomic identity, such as the mandible from Atapuerca and Orce, are not directly comparable. However, parietal from the Aurora stratum of Atapuerca and aged 900 ka share some features (orbital roof convexity, dimensions), which may be due to the age of the individuals. Nonetheless, the lineage may have dispersed from Africa 1.6-1.2 mya into the Mediterranean.[2] Antón and Middleton (2023), in their review of the taxon Homo erectus, assign Kocabaş to their "unknown, ?H. erectus" group.[7]

Paleoecology

The skull was discovered alongside Archidiskodon merionalis meridionalis and Palaeotragus, which together form an Upper Villafranchian fauna that was comprehensively catalogued during 2011-2012 field missions. The exact location of the calvarium was not recorded, but it was thought to have been found in the Faber Quarry, which reaches down 90 m and has stratigraphy that is comparable to the slab containing the hominin. Revised age estimates of this quarry includes 1.6 mya at minimum and 1.1 mya at minimum, although the skull probably belongs to the 1.3-1.1 mya range.[3] No lithics were reported, but Vialet et al. (2018) suggested based on chronology that these populations may have produced technology similar to the Oldowan or Acheulean.[2] Overlying the hominin is 20 m of shallow alkaline lake deposits bearing many ostracod fossils representing 16 taxa and dated 1.6-1.1 mya. The salinity is no greater than lower mesohaline, and the body was probably limited because of a loss of taxic diversity. Nearby travertine would have deposited calcium-rich water, which would have greatly affected the fauna.[8]

References

- Vialet, Amélie; Guipert, Gaspard; Cihat Alçiçek, Mehmet (2012-03-01). "Homo erectus found still further west: Reconstruction of the Kocabaş cranium (Denizli, Turkey)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. Mainland and insular Asia: Current debates about first settlements L'Asie continentale et insulaire : quelques points d?actualité sur les premiers peuplements. 11 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2011.06.005. ISSN 1631-0683.

- Vialet, Amélie; Prat, Sandrine; Wils, Patricia; Cihat Alçiçek, Mehmet (2018-01-01). "The Kocabaş hominin (Denizli Basin, Turkey) at the crossroads of Eurasia: New insights from morphometric and cladistic analyses". Comptes Rendus Palevol. Hominins and tools. Expansion from Africa towards Eurasia / Homininés et outils. Expansions depuis l’Afrique vers l’Eurasie. 17 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2017.11.003. ISSN 1631-0683.

- Lebatard, Anne-Elisabeth; Alçiçek, M. Cihat; Rochette, Pierre; Khatib, Samir; Vialet, Amélie; Boulbes, Nicolas; Bourlès, Didier L.; Demory, François; Guipert, Gaspard; Mayda, Serdar; Titov, Vadim V.; Vidal, Laurence; de Lumley, Henry (2014-03-15). "Dating the Homo erectus bearing travertine from Kocabaş (Denizli, Turkey) at at least 1.1 Ma". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 390: 8–18. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2013.12.031. ISSN 0012-821X. S2CID 129308837.

- Wilford, John Noble (2007-12-18). "Signs of TB in Ancient Skull Support Theory on Vitamin D". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-09-10.

- Roberts, Charlotte A.; Pfister, Luz‐Andrea; Mays, Simon (2009). "Letter to the editor: Was tuberculosis present in Homo erectus in Turkey?". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 139 (3): 442–444. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21056. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 19358292.

- Baab, Karen L. (2008-06-01). "The taxonomic implications of cranial shape variation in Homo erectus". Journal of Human Evolution. 54 (6): 827–847. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.11.003. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 18191986.

- Antón, Susan C.; Middleton, Emily R. (2023-06-01). "Making meaning from fragmentary fossils: Early Homo in the Early to early Middle Pleistocene". Journal of Human Evolution. 179: 103307. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2022.103307. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 37030994. S2CID 258014849.

- Rausch, Lea; Stoica, Marius (2019-09-06). "AN EARLY PLEISTOCENE ANOMALOHALINE WATER OSTRACOD FAUNA FROM LAKE DEPOSITS OF THE HOMO ERECTUS-BEARING KOCABAŞ LOCALITY (SW TURKEY)". Acta Palaeontologica Romaniae. 15 (2): 40–68. doi:10.35463/j.apr.2019.02.04. ISSN 1842-371X. S2CID 203090984.