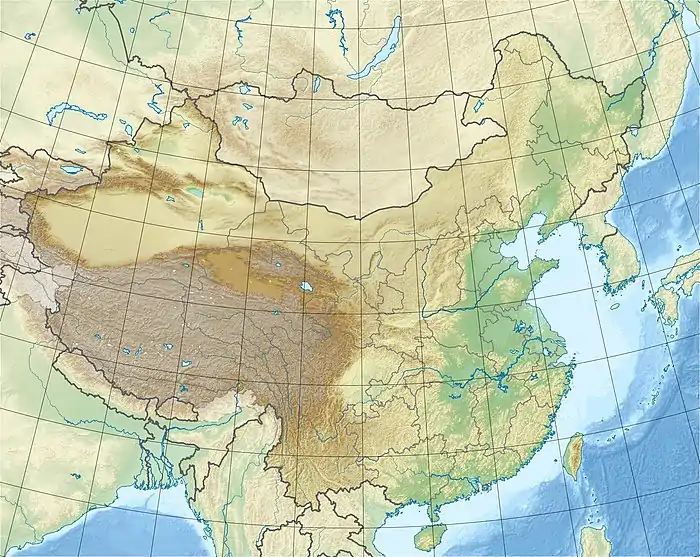

Qinghai Lake

Qinghai Lake or Ch'inghai Lake, also known by other names, is the largest lake in China. Located in an endorheic basin in Qinghai Province, to which it gave its name, Qinghai Lake is classified as an alkaline salt lake. The lake has fluctuated in size, shrinking over much of the 20th century but increasing since 2004. It had a surface area of 4,317 km2 (1,667 sq mi), an average depth of 21 m (69 ft), and a maximum depth of 25.5 m (84 ft) in 2008.

| Qinghai Lake | |

|---|---|

From space (November 1994). North is to the left. | |

Qinghai Lake  Qinghai Lake | |

| Location | Qinghai |

| Coordinates | 37°00′N 100°08′E |

| Type | Endorheic salt lake |

| Basin countries | China |

| Surface area | 4,186 km2 (1,616 sq mi) (2004) 4,489 km2 (1,733 sq mi) (2007)[1] 4,543 km2 (1,754 sq mi) (2020)[2] |

| Max. depth | 32.8 m (108 ft) |

| Water volume | 108 km3 (26 cu mi) |

| Surface elevation | 3,260 m (10,700 ft) |

| Islands | Sand Island, Bird Islands |

| Settlements | Haiyan County |

| References | [1] |

Names

| Qinghai Lake | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 靑海湖 or 青海湖 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Grue Sea Lake Blue Sea Lake | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | མཚོ་སྔོན་པོ་ མཚོ་ཁྲི་ཤོར་རྒྱལ་མོ་ | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Хөх нуур | ||||||||||||||

| Mongolian script | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡥᡠᡥᡠ ᠨᠣᠣᡵ | ||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Huhu Noor | ||||||||||||||

| Former names | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xihai | |||||||||||||

| Chinese | 西海 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Western Sea | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Qinghai is the romanized Standard Chinese pinyin pronunciation of the name 青海. Although modern Chinese distinguishes between the colors blue and green, this distinction did not exist in classical Chinese. The color 青 (qīng) was a "single" color inclusive of both blue and green as separate shades. (English for qīng is cyan or turquoise, also linguists have coined the portmanteau "grue" to discuss its existence in Chinese and other languages.)[3] The name is thus variously translated as "Blue Sea",[4] "Green Sea",[5] "Blue-Green Sea",[6] "Blue/Green Sea",[7] etc. For a time after its wars with the Xiongnu, Han China connected the lake with the legendary "Western Sea" assumed to balance the East China Sea, but as the Han Empire expanded further west into the Tarim Basin other lakes assumed the title.[8]

In English, Qinghai Lake was formerly known as Ch'inghai Lake or Koko Nor;[9] the Chinese Postal Map romanization was of the Mongolian name ᠬᠥᠬᠡ ᠨᠠᠭᠤᠷ. As for the Mongolians, the color of the lake is unambiguously labeled blue, but classical Mongolian did not distinguish between lakes and larger bodies of water. The Chinese name, using "sea" rather than "lake," is thus an overly literal calque of this name,[6][10] used by the Upper Mongols, some of whom made up the local ruling class during the standardization of western Chinese toponyms in the Qing dynasty.[11] Similar use of the Chinese word for "sea" to translate Mongolian lake toponyms can be seen elsewhere around Qinghai, as with Lake Heihai ("Black Sea") in the Kunlun Mountains.

The Tibetans also separately calqued the name as Tibetan: མཚོ་སྔོན་པོ་, Wylie: Mtsho-sngon-po, THL: Tso ngönpo "Blue Lake, Sea".

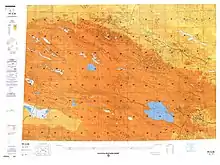

Geography

Qinghai Lake lies about 100 kilometers (62 mi) west of Xining in a hollow of the Tibetan Plateau at 3,205 meters (10,515 ft) above sea level.[12] It lies between Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture and Hainan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in northeastern Qinghai in Northwest China. The lake has fluctuated in size, shrinking over much of the 20th century but increasing since 2004. It had a surface area of 4,317 square kilometers (1,667 sq mi), an average depth of 21 meters (69 ft), and a maximum depth of 25.5 m (84 ft) in 2008.[13]

Twenty-three rivers and streams empty into Qinghai Lake, most of them seasonal. Five permanent streams provide 80% of the total influx.[14] The relatively low inflow and high evaporation rates have turned Qinghai saline and alkaline; the salt concentration is presently about 1.4% by weight (seawater has a salt concentration of about 3.5%), with a pH of 9.3.[15] It has increased in salinity and basicity since the early Holocene.[15]

At the tip of the peninsula on the western side of the lake are Cormorant Island and Egg Island, collectively known as the Bird Islands.

Qinghai Lake became isolated from the Yellow River about 150,000 years ago.[15] If the water level were to rise by approximately 50 meters (160 ft), the connection to the Yellow River would be reestablished via the low pass to the east used by highway S310.

18,000 years ago, just after the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, the lake level of Lake Qinghai was around 30 metres lower than today. Between 15,600 and 10,700 years ago, lake levels secularly increased to around 10 metres lower than the present lake level, after which they declined slightly until around 9,200 years ago, when they began to rise again. Around 5,900 years ago, lake levels reached a peak of a few metres higher than today, before declining again amidst a regional cooling and drying trend until 1,400 years ago, when they were less than 10 metres lower than average modern levels. They then began to rise once more until reaching their present level.[16]

Climate

The lake often remains frozen for three months continuously in winter.[17]

| Climate data for Qinghai Lake (1981−2010 normals, extremes 1981−2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

8.8 (47.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

19.1 (66.4) |

22.8 (73.0) |

23.7 (74.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −5.2 (22.6) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

3.2 (37.8) |

7.9 (46.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.1 (62.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −12.3 (9.9) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

1.3 (34.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.7 (53.1) |

11.3 (52.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

0.8 (33.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −17.9 (−0.2) |

−15.5 (4.1) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

0.7 (33.3) |

4.4 (39.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

5.9 (42.6) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−13.9 (7.0) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.9 (−16.4) |

−25.8 (−14.4) |

−23.6 (−10.5) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−26.9 (−16.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1 (0.0) |

2 (0.1) |

6 (0.2) |

17 (0.7) |

45 (1.8) |

65 (2.6) |

87 (3.4) |

85 (3.3) |

54 (2.1) |

20 (0.8) |

3 (0.1) |

1 (0.0) |

386 (15.1) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 48 | 44 | 46 | 53 | 61 | 70 | 73 | 73 | 72 | 60 | 47 | 49 | 58 |

| Source 1: China Meteorological Data Service Center[17] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: www.yr.no (temperature averages) [18] | |||||||||||||

History

During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), substantial numbers of Han Chinese lived in the Xining valley to the east.[8] In the 17th century, Mongolic-speaking Oirat and Khalkha tribals migrated to Qinghai and became known as Qinghai Mongols.[19] In 1724, the Qinghai Mongols led by Lobzang Danjin revolted against the Qing Dynasty. The Yongzheng Emperor, after putting down the rebellion, stripped away Qinghai's autonomy and imposed direct rule. Although some Tibetans lived around the lake, the Qing maintained an administrative division from the time of Güshi Khan between the Dalai Lama's western realm (slightly smaller than the current Tibet Autonomous Region) and the Tibetan-inhabited areas in the east. Yongzheng also sent Manchu and Han settlers to dilute the Mongols.[20]

During Nationalist rule (1928-1949), the Han formed a majority of Qinghai Province's residents, although Chinese Muslims (Hui) dominated the government.[21] The Kuomintang Hui general Ma Bufang, having invited Kazakh Muslims,[22] joined the governor of Qinghai and other high ranking Qinghai and national government officials in conducting a joint Kokonuur Lake Ceremony to worship the God of the Lake. During the ritual, the Chinese national anthem was sung and all participants bowed to a Portrait of Kuomintang founder Sun Yat-sen as well as to the God of the Lake. Participants, both Han and Muslim, made offerings to the god.[23]

After the 1949 Chinese revolution, refugees from the 1950s Anti-Rightist Movement settled in the area west of Qinghai Lake.[8] After the Chinese economic reform in the 1980s, drawn by new business opportunities, migration to the area increased, causing ecological stresses. Fresh grass production in Gangcha County north of the lake declined from a mean of 2,057 kilograms per hectare (1,835 lb/acre) to 1,271 kg/ha (1,134 lb/acre) in 1987. In 2001, the State Forestry Administration of China launched the "Retire Cropland, Restore Grasslands" (退耕,还草) campaign and started confiscating Tibetan and Mongol pastoralists' guns in order to preserve the endangered Przewalski's gazelle.[8]

Prior to the 1960s, 108 freshwater rivers emptied into the lake. As of 2003, 85% of the river mouths have dried up, including the lake's largest tributary, the Buha River. In between 1959 and 1982, there had been an annual water level drop of 10 centimeters (3.9 in), which was reversed at a rate of 10 cm/year (3.9 in/year) between 1983 and 1989, but has continued to drop since. The Chinese Academy of Sciences reported in 1998 the lake was again threatened with loss of surface area due to livestock over-grazing, land reclamations, and natural causes.[24] Surface area decreased 11.7% in the period from 1908 to 2000.[25] During that period, higher lake floor areas were exposed and numerous water bodies separated from the rest of the main lake. In the 1960s, the 48.9-square-kilometer (18.9 sq mi) Gahai Lake (尕海, Gǎhǎi) appeared in the north; Shadao Lake (沙岛, Shādǎo), covering an area of 19.6 km2 (7.6 sq mi) to the northeast, followed in the 1980s, along with Haiyan Lake (海晏, Hǎiyàn) of 112.5 km2 (43.4 sq mi).[26] Another 96.7 km2 (37.3 sq mi) daughter lake split off in 2004. In addition, the lake has now split into half a dozen more small lakes at the border. Qinghai Provincial Remote Sensing Center, attributed the separation of Qinghai Lake to shrinkage of the water surface as a result of a lowered water level and desertification in the region. The water surface has shrunk by 312 km2 (120 sq mi) over the last three decades.[27]

Wildlife

The lake is located at the crossroads of several bird migration routes across Asia. Many species use Qinghai as an intermediate stop during migration. As such, it is a focal point in global concerns regarding avian influenza (H5N1), as a major outbreak here could spread the virus across Europe and Asia, further increasing the chances of a pandemic. Minor outbreaks of H5N1 have already been identified at the lake. The Bird Islands have been sanctuaries of the Qinghai Lake Natural Protection Zone since 1997.

There are five native fish species: The edible naked carp (Gymnocypris przewalskii, 湟鱼; huángyú),[28] which is the most abundant in the lake, and four stoneloaches (Triplophysa stolickai, T. dorsonotata, T. scleroptera and T. siluroides).[15] Other Yellow River fish species occurred in the lake, but they disappeared with the increasing salinity and basicity, beginning in the early Holocene.[15]

Culture

There is an island in the western part of the lake with a temple and a few hermitages called "Mahādeva, the Heart of the Lake" (mTsho snying Ma hā de wa) which historically was home to a Buddhist monastery. The temple was also used for religious purposes and ceremonies.[29] No boat was used during summer, so monks and pilgrims traveled to and from only when the lake froze over in winter. A nomad described the size of the island by saying that: "if in the morning a she-goat starts to browse the grass around it clockwise and its kid anti-clockwise, they will meet only in the night, which shows how big the island is."[30] It is also known as the place to which Gushri Khan and other Khoshut Mongols migrated during the 1620s.[31]

The lake is currently circumnavigated by pilgrims, mainly Tibetan Buddhists, especially every Horse Year of the 12-year cycle. Nikolay Przhevalsky estimated it would take about eight days by horse or 15 walking to circumambulate the lake, but pilgrims report it takes about 18 days on horseback, and one took 23 days walking to complete the circuit.[32]

Gallery

Rapeseed fields

Rapeseed fields Grassland near the lake

Grassland near the lake Gya'yi Monastery (རྒྱ་ཡེ་དགོན) at Qinghai Lake

Gya'yi Monastery (རྒྱ་ཡེ་དགོན) at Qinghai Lake Yurt on the shore

Yurt on the shore

See also

References

Citations

- "Area of Qinghai Lake Has Increased Continuously". China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved August 28, 2008.

- 青海湖面积较上年同期增大28平方公里. Xinhua News. 21 May 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Hamer (2016).

- Columbia Encycl. (2001).

- Lorenz, Andreas (31 May 2012), "Old and New China Meet along the Yellow River", Der Spiegel, Hamburg: Spiegel Verlag.

- Bell (2017), p. 4.

- Zhu & al. (1999), p. 374.

- Harris (2008), pp. 130–132.

- Stanford (1917), p. 21.

- Huang (2018), p. 58.

- Xiyu Tongwen Zhi (1763).

- Buffetrille 1994, p. 2; Gruschke 2001, pp. 90 ff.

- Zhang, Guoqing (2011). "Water level variation of Lake Qinghai from satellite and in situ measurements under climate change". Journal of Applied Remote Sensing. 5 (1): 053532. Bibcode:2011JARS....5a3532Z. doi:10.1117/1.3601363. S2CID 53463010.

- Rhode, David; Ma Haizhou; David B. Madsen; P. Jeffrey Brantingham; Steven L. Forman; John W. Olsen (2009). "Paleoenvironmental and archaeological investigations at Qinghai Lake, western China: Geomorphic and chronometric evidence of lake level history" (PDF). Quaternary International. 218 (1–2): 3. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2009.03.004. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- Zhang & al. (2015).

- Wang, Zheng; Zhang, Fan; Li, Xiangzhong; Cao, Yunning; Hu, Jing; Wang, Huangye; Liu, Hongxuan; Li, Ting; Liu, Weiguo (May 2020). "Changes in the depth of Lake Qinghai since the last deglaciation and asynchrony between lake depth and precipitation over the northeastern Tibetan Plateau". Global and Planetary Change. 188: 103156. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2020.103156. S2CID 216231872. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- 中国地面气候标准值月值(1981-2010) (in Chinese (China)). China Meteorological Data Service Center. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- "Climate: Qinghai Lake, China". Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- Sanders (2010), pp. 2–3, 386, 600.

- Perdue (2005), pp. 310–312.

- Hutchings (2003), p. 351.

- Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-7425-1144-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002), p. 51.

- "China's Qinghai Lake drying up". World Tibet Network News. March 27, 1998. Archived from the original on May 29, 2004. Retrieved May 29, 2004.

- People's Daily. Archived 2016-11-11 at the Wayback Machine

- "Two New Saltwater Lakes Separate from Qinghai Lake". fpeng.peopledaily.com. 2001-10-26. Archived from the original on 2003-11-07.

- Qinghai Lake splits due to deterioration. Chinadaily.com.cn (2004-02-24). Retrieved on 2010-09-27.

- Su (2008), p. 19.

- Gruschke (2001).

- Buffetrille (1994), pp. 2–3.

- Shakabpa (1962).

- Buffetrille (1994), p. 2.

Bibliography

- "Qinghai", Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.), New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

- 《欽定西域同文志》 [Imperial Glossary of the Western Regions] (in Chinese), Beijing, 1763.

- Bell, Daniel (2017). Syntactic Change in Xining Mandarin (PDF) (PhD thesis). Newcastle: Newcastle University..

- Buffetrille, Katia (Winter 1994), "The Blue Lake of Amdo and Its Island: Legends and Pilgrimage Guide", The Tibet Journal, XIX (4).

- Gruschke, Andreas (2001), "The Realm of Sacred Lake Kokonor", The Cultural Monuments of Tibet's Outer Provinces, vol. I: The Qinghai Part of Amdo, Bangkok: White Lotus Press, pp. 93 ff, ISBN 974-7534-59-2.

- Hamer, Ashley (10 June 2016), "What the Color Grue Means about the Impact of Language", Curiosity.

- Harris, Richard B. (2008), Wildlife Conservation in China: Preserving the Habitat of China's Wild West, M.E. Sharpe.

- Huang Fei (2018), Dongchuan in Eighteenth-Century Southwest China, Reshaping the Frontier Landscape, Vol. 10, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 9789004362567.

- Hutchings, Graham (2003), Modern China: A Guide to a Century of Change, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, p. 351.

- Perdue, Peter C. (2005), China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Sanders, Alan (2010), Historical Dictionary of Mongolia, Scarecrow Press.

- Shakabpa, Tsepon W.D. (1962), Tibet: A Political History, New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Stanford, Edward (1917), Complete Atlas of China, 2nd ed., London: China Inland Mission.

- Su Shuyang (2008), China: Ein Lesebuch zur Geschichte, Kultur, und Zivilisation (in German), Wissenmedia Verlag, ISBN 978-3-577-14380-6.

- Zhang; et al. (2015), "Article 9780: Gymnocypris przewalskii (Cyprinidae) on the Tibetan Plateau", Scientific Reports, vol. 5.

- Zhu Yongzhong; et al. (1999), "Education among the Minhe Monguo", China's National Minority Education: Culture, Schooling, and Development, New York: Falmer Press, pp. 341–384, ISBN 9781135606626.

External links

Media related to Lake Qinghai at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lake Qinghai at Wikimedia Commons- (in Chinese) Qinghai Lake Protection and Utilization Administration Bureau (official)

- (in Chinese) Qinghai Lake Tourism and Culture Network (official)

- More Birds in Qinghai Lake (Eastday.com.cn 07/17/2001)

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.