Khonds

Khonds (also spelt Kondha and Kandha) are an indigenous Adivasi tribal community in India. Traditionally hunter-gatherers, they are divided into the hill-dwelling Khonds, and plain-dwelling Khonds for census purposes, but the Khonds themselves identify by their specific clans. Khonds usually hold large tracts of fertile land, but still practice hunting, gathering, and slash-and-burn agriculture in the forests as a symbol of their connection to, and as an assertion of their ownership of the forests wherein they dwell. Khonds speak the Kui language and write it in the Odia script.

A Khond woman in Odisha | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Odisha | 1,627,486 (2011 census)[1] |

| Languages | |

| Kui, Kuvi, Odia | |

| Religion | |

| Currently mostly Hinduism and Christianity[2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Dravidian people • Dangaria Kandha • Gondi people | |

The Khonds are the largest tribal group in the state of Odisha. They are known for their rich cultural heritage, valourous martial traditions, and indigenous values, which center on harmony with nature. The Kandhamal district in Odisha has a fifty-five percent Khond population, and is named after the tribe.

They are a designated Scheduled Tribe in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Jharkhand and West Bengal.[3]

Language

The Khonds speak Kui and Kuvi as their native languages. They are most closely related to the Gondi language. Both are Dravidian languages and are written with the Odia script.[4]

Society

The Khonds are adept land dwellers of the forest and hill environment. However, due to development interventions in education, medical facilities, irrigation, plantation, they have adapted to the modern way of life in many ways. Their traditional lifestyle, language, food habits, customary traits of economy, political organization, norms, values, and world view have been drastically changed in recent times.

The traditional Khond society is based on geographically demarcated clans, each consisting of a large group of related families identified by a Totem, usually of a male wild animal. Each clan usually has a common surname and is led by the eldest male member of the most powerful family of the clan. All the clans of the Khonds owe allegiance to the "Kondh Pradhan", who is usually the leader of the most powerful clan of the Khonds.

The Khond family is often nuclear, although extended joint families are also found. Female family members are on equal social footing with the male members in Khond society, and they can inherit, own, hold, and dispose of property without reference to their parents, husband or sons. Women have the right to choose their husbands, and to seek divorce. However, the family is patrilineal and patrilocal. Remarriage is common for divorced or widowed women and men. Children are never considered illegitimate in Khond society and inherit the clan name of their biological or adoptive fathers with all the rights accruing to natural born children.

The Kondhs have a dormitory for adolescent girls and boys which forms a part of their enculturation and education process. The girls and boys sleep at night in their respective dormitory and learn social taboos, myths, legends, stories, riddles, proverbs amidst singing and dancing the whole night, thus learning the way of the tribe. The girls are usually instructed in good housekeeping and in ways to bring up good children while the boys learn the art of hunting and the legends of their brave and martial ancestors.

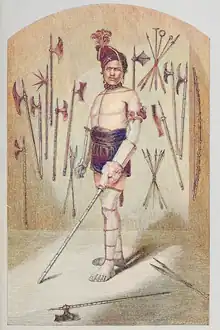

Bravery and skill in hunting determine the respect that a man gets in the Khond tribe. A large number of Khonds were recruited by the British during the First and Second World Wars and were prized as natural jungle warfare experts and fierce warriors. Even today a large proportion of the Khond men join the State police or Armed Forces of India to seek an opportunity to prove their bravery. Modern education has facilitated the entry of a large number of Khonds into Government Civil Service, and adaptation to modern life has ensured that the tribe is one of the most politically dominant in Odisha.

The men usually forage or hunt in the forests. They also practise the podu system of shifting cultivation on the hill slopes where they grow different varieties of rice, lentils and vegetables. Women usually do all the household work from fetching water from the distant streams, cooking, serving food to each member of the household to assisting the men in cultivation, harvesting and sale of produce in the market.[5]

The Khond commonly practice clan exogamy. By custom, marriage must cross clan boundaries (a form of incest taboo). The clan is strictly exogamous, which means marriages are made outside the clan (yet still within the greater Khond population). The form of acquiring mate is often by negotiation. However, marriage by capture or elopement is also rarely practiced. For marriage bride price is paid to the parents of the bride by the groom, which is a striking feature of the Khonds. The bride price was traditionally paid in tiger pelts though now land or gold sovereigns are the usual mode of payment of bride price.

Religious beliefs

_(14783429545).jpg.webp)

Traditionally the Khond religious beliefs were syncretic combining totemism, animism, ancestor worship, shamanism and nature worship. British writers also note that the Khonds practiced human sacrifice.[6] Traditional Khond religion involved the worship mountains, Rivers, Sun, Earth. Baredi is place of worship. Traditional Khond religion involved different rituals such as Jhagadi or Kedu or Meriah Puja, Sru Penu Puja, Dharni Penu Puja, Guruba Penu Puja, Turki Penu Puja, and Pitabali Puja. Matiguru involved worship of earth through before sowing seeds. Other rituals connected with land fertility were 'Guruba Puja', 'Turki Puja' and in some cases 'Meriah Puja (human sacrifice)' to appease Dharni (earth). Saru penu puja involved the sacrifice of fowls and feast. In Dehuri sacrifice goat and chicken were sacrificed. Gurba Penu Puja and Turki penu puja performed outside the village. Pitabali Puja was performed by offering flowers, fruits, sandal paste, incense, ghee-lamps, ghee, sundried rice, turmeric, buffalo or a he-goat and fowl.[7]

The Traditional Khond religion gave highest importance to the Earth goddess, who is held to be the creator and sustainer of the world. The gender of the deity changed to male and became Dharni Deota. His companion is Bhatbarsi Deota, the hunting god. To them once a year a buffalo was sacrificed. Before hunting they would worship the spirit of the hills and valleys they would hunt in lest they hide the animals the hunter wished to catch.

In Traditional Khond religion, a breach of accepted religious conduct by any member of their society invited the wrath of spirits in the form of lack of rain fall, soaking of streams, destruction of forest produce, and other natural calamities. Hence, the customary laws, norms, taboos, and values were greatly adhered to and enforced with high to heavy punishments, depending upon the seriousness of the crimes committed. The practise of traditional Khond religion has practically become extinct today.

Extended contact with the Oriya speaking Hindus made Khonds to adopt many aspects of Hinduism and Hindu culture. The contact with the Hindus led the Khonds to adopt Hindu deities into their pantheon and rituals. For example, the Kali and Durga are worshiped as manifestations of Dharani, but always with the sacrifice of buffaloes, goats, or fowl. Similarly, Shiva is worshipped as a manifestation of Bhatbarsi Deota with tribal rituals not seen in Hinduism. Jagganath, Ram, Krishna and Balram are other popular deities who have been "tribalised" in Khond adaptation of Hinduism.[8]

Many Khonds converted to Protestant Christianity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century due to the efforts of the missionaries of the Serampore Mission. The influence of Khond traditional beliefs on Christianity can be seen in some rituals such as those associated with Easter and resurrection when ancestors are also venerated and given offerings, although the church officially rejects the traditional beliefs as pagan. Many Khonds have also converted to Islam and a great diversity of religious practises can be seen among the members of the tribe. There is widespread religious diversity within the tribe, and often within the same family. However, the Khond tribal identity and affiliation predominates the social and ethical culture far more than individual religious faith.

Significantly, as with many indigenous peoples, the conceptual worldview of the natural environment and its sacredness subscribed to by the Khond reinforce the social and cultural practices that define the tribe. Here, the sacredness of the earth perpetuates tribal socio-ethics, wherein harmony with nature and respect for ancestors is deeply embedded. This is in stark contrast to non tribal, materialistic, economics-centred, resource extractive worldview that may not prioritise the primacy of the land or acknowledge environment as a spiritual and cultural resource and thereby promote deforestation, strip-mining etc. for development projects. This divergence in worldviews of the Khonds with the Policy makers has led to a situation of conflict in many instances.[9]

Economy

They have an economy based on hunting and gathering, trapping game, collecting wild fruits, tubers and honey apart from subsistence agriculture i.e. shifting cultivation or slash-and-burn cultivation, locally called Podu.[10] The Khonds are excellent fruit farmers. The most striking feature of the Khonds is that they have adapted to horticulture and grow pineapple, oranges, turmeric, ginger and papaya in plenty. Forest fruit trees like mango and jackfruit, Mahua, Guava, Tendu and Custard apples are collected, which fulfill the major dietary chunk of the Khonds. Besides, the Khonds practice shifting cultivation, or podu chasa as it is locally called, as part of agriculture for growing lentils, beans and millets retaining the most primitive features of agricultural underdevelopment. Millets and beans along with game and fish form the staple diet of the Khonds. A dietary shift from millets to carbohydrate rich, processed foods has led to an obesity and diabetes among tribals. Turmeric grown in the Kandhamal district by the Khonds is a registered Geographical Indication product.

The Khonds grow several native cultivars of fragrant and coloured rice. Parboiled rice is preferred as a staple.

They go out for collective hunts as well collect the seasonal fruits and roots in the forest. They usually cook food with oil extracted from sal and mahua seeds. They also use medicinal plants. These practices make them mainly dependent on forest resources for survival. The Khonds smoke fish and meat for preservation.

Uprisings

The Khonds are a fiercely independent tribe of formidable, bold and aggressive warriors who have risen up against the colonial authority on numerous occasions. For example, from 1753 to 1856 in the century long Ghumsar uprising the Khonds rebelled against the rule of the East India Company and carried out sustained guerilla warfare as well as pitched combat against the British.[11][12]

Social and environmental concerns

The Dongria clan of Khonds inhabit the steep slopes of the Niyamgiri Range of Koraput district and over the border into Kalahandi. They work entirely on the steep slopes for their livelihood. Vedanta Resources, a UK-based mining company, threatened the future of homeland of the Dongria Khonds clan of this tribe who reside in the Niyamgiri Hills which has rich deposits of bauxite.[13] The bauxite mining also threatened the source and potability perennial streams in the Niyamgiri Hills.

The tribe's plight was the subject of a Survival International short film narrated by actress Joanna Lumley.[14] In 2010 India's environment ministry ordered Vedanta Resources to halt a sixfold expansion of an aluminium refinery in Odisha.[15][16] As part of its Demand Dignity campaign, in 2011 Amnesty International published a report concerning the rights of the Dongria Kondh.[17][18]

Celebrities backing the campaign included Arundhati Roy (the Booker prize-winning author), as well as the British actors Joanna Lumley and Michael Palin.[18]

In April 2013, the Supreme Court in a landmark decision, Orissa Mining Corporation Ltd vs Ministry Of Environment & Forest dated 18 April 2013, upheld the ban on Vedanta's project in the Niyamgiri Hills, ruling that development projects can not be at the cost of Constitutional cultural and religious fundamentaal rights of the Khonds and directed that the consent of the Khond community affected by the Vedanta project must be obtained prior to commencement.

The Khonds voted against the project in August 2013, and in January 2014 the Ministry for Environment and Forests stopped the Vedanta project.[19]

The Niyamgiri movement and the resultant decision of the Supreme Court is considered a major milestone in indigenous rights jurisprudence in India.

Communal unrest and insurgency

On 25 December 2007, ethnic conflict broke out between Khond tribals and Pano Scheduled Caste people in Kandhamals.

On 23 August 2008, Hindu ascetic Swami Lakshmanananda Saraswati - who worked among the Khond tribals for their educational upliftment - was murdered along with four others, including a boy by a team of Maoist gunmen which allegedly included Catholic Panos. Maoist rebels took responsibility for the multiple murders.[20] This led to large-scale riots between the indigenous ethnic Kandha tribe and the Scheduled Caste Pano communities. The underlying causes are complex and cross political and religious boundaries.[21] Land encroachment, perceived or otherwise, was the main source of tension between the Khond and Pano communities. It was widely believed by the Khonds that Panos were purchasing tribal land by forged documents wherein they were shown to be Khonds. The clash was predominantly ethnic, as both Hindu Kondhs and Protestant Christian Kondhs were on the same side, fighting against Catholic and Hindu Panos.

Later the conflict assumed communal overtones, as it was projected by western media to be a persecution of "Christian Minorities" rather than an ethnic conflict for land resources.

In April 2010, a special "fast track" court in Phulbani convicted 105 people.[22] Ten people were acquitted due to lack of evidence.

Kandhamal district is currently a part of the Red Corridor of India, an area with significant Maoist insurgency activity.[23] Suspected Maoist rebels detonated a roadside land mine on 27 November 2010, blowing up an ambulance. A patient, a paramedic, and the vehicle's driver were killed.[24]

See also

- Kandhamal, district

- Naxalite-Maoist Insurgency in India Red Corridor

- Lakshmanananda Saraswati

References

- "A-11 Individual Scheduled Tribe Primary Census Abstract Data and its Appendix". www.censusindia.gov.in. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "ST-14 Scheduled Tribe Population By Religious Community - Odisha". census.gov.in. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- "List of notified Scheduled Tribes" (PDF). Census India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Kui (India)". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Jena M. K., et.al. Forest Tribes of Orissa: Lifestyles and Social Conditions of selected Orissan Tribes, Vol.1, Man and Forest Series 2, New Delhi, 2002, pages -13-18.

- Russell, Robert Vane (1916). pt. II. Descriptive articles on the principal castes and tribes of the Central Provinces. Macmillan and Company, limited.

- "Shifting Cultivation by the Juangs of Orissa". etribaltribue. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- "konds". Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Hardenberg, Roland, Children of the Earth Goddess:Society, Sacrifice and Marriage in the Highlands of Orissa in Transformations in Sacrificial Practices: From Antiquity to Modern Times ...By Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, Axel Michaels, Claus Ambos, Lit Verlag Muster, 2005, pages -134.

- "Kandha Hand Book" (PDF). Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- Behera, Maguni Charan (2021). "Against the British: Kandha Leadership in Ghumsar Uprising (1753–1856)". Tribe British Relations in India. Springer. pp. 237–257. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-3424-6_15. ISBN 9789811634246. S2CID 239219992.,

- Kumar, Raj (2004). Essays on Social Reform Movements. Discovery Publishing House. p. 266. ISBN 978-8-17141-792-6.

- "Tribe takes on global mining firm". BBC. 17 July 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- Survival International

- "India blocks Vedanta mine on Dongria-Kondh tribe's sacred hill". Guardian News and Media Ltd. 24 August 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- "India puts stop to expansion of Vedanta aluminium plant". BBC. 21 October 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- India: Generalisations, omissions, assumptions: The failings of Vedanta’s Environmental Impact Assessments for its bauxite mine and alumina refinery in India’s state of Odisha (Executive Summary) Amnesty International.

- "Indian tribe's Avatar-like battle against mining firm reaches supreme court". Guardian News and Media Ltd. 8 April 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- "Vedanta Resources lawsuit (re Dongria Kondh in Orissa)". Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- "Majority of Maoist supporters in Orissa are Christians". The Hindu. PTI. Archived from the original on 8 October 2008.

- "India's remote faith battleground". BBC News. 26 September 2008.

- Sib Kumar Das (1 April 2010). "7 sentenced in Kandhamal riots cases". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- "83 districts under the Security Related Expenditure Scheme". IntelliBriefs. 11 December 2009. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- "Report: Suspected rebels kill 3 in eastern India". The Guardian. London. 28 November 2010.

External links

- Pictures

- Sinlung Sinlung - Indian tribes

- Dongria Kondh Survival International (Includes Images)

- A 5 minute video about the tribe and the challenges they face from Vedanta Resources