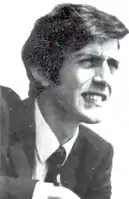

Kostas Georgakis

Kostas Georgakis (Greek: Κώστας Γεωργάκης) (23 August 1948 – 19 September 1970) was a Greek student studying geology in Italy. On 26 July 1970, while in Italy, he gave an interview denouncing the dictatorial regime of Georgios Papadopoulos. The junta retaliated by attacking him, pressuring his family, and rescinding his military exemption. In a final, fatal, protest in the early hours of 19 September 1970, Georgakis set himself ablaze in Matteotti square in Genoa. He died later that day, an estimated 1,500 people attended his 22 September funeral, with hundreds of anti-junta resistance members leading a demonstration. Melina Mercouri carried a bouquet for the hero of the anti-junta. After being briefly interred in Genoa his remains were transported by ship to Corfu, and on 18 January 1971 he was buried. After the junta collapsed the Government of Greece erected a monument and plaque in his home town of Corfu, another plaque was placed in Matteotti square, and multiple poems have been written in his honor.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Early life

Georgakis grew up in Corfu in a family of five. His father was a self-employed tailor of modest means. Both his father and grandfather distinguished themselves in the major wars that Greece fought in the 20th century. He attended the second lyceum in Corfu where he excelled in his studies. In August 1967, a few months after the 21 April coup in Greece, Georgakis went to Italy to study as a geologist in Genoa. He received 5,000 drachmas per month from his father and this, according to friends' testimony, made him feel guilty for the financial burden his family endured so that he could attend a university. In Italy he met Rosanna, an Italian girl of the same age and they got engaged.[7] In 1968 Georgakis became a member of the Center Union party of Georgios Papandreou.[8]

Protest

On 26 July 1970, Georgakis gave an anonymous interview to a Genovese magazine, during which he revealed that the military junta's intelligence service had infiltrated the Greek student movement in Italy.[8] In the interview he denounced the junta and its policies and stated that the intelligence service created the National League of Greek students in Italy and established offices in major university cities.[8] A copy of the recording of the interview was obtained by the Greek consulate and the identity of Georgakis was established.[8]

Soon after, he was attacked by members of the junta student movement. While in the third year of his studies and having passed the exams of the second semester Georgakis found himself in the difficult position of having his military exemption rescinded by the junta as well as his monthly stipend that he received from his family.[9] The junta retaliated for his involvement in the anti-junta resistance movement in Italy as a member of the Italian branch of PAK.[7] His family in Corfu also sent him a letter describing the pressure that the regime was applying to them.[8][10]

Fearing for his family in Greece, Georgakis decided that he had to make an act to raise awareness in the West about the political predicament of Greece.[8] Once he made the decision to sacrifice his life, Georgakis filled a canister with gasoline, wrote a letter to his father and gave his fiancée Rosanna his windbreaker telling her to keep it because he would not need it any longer.[10]

Around 1:00 a.m. on 19 September 1970, Georgakis drove his Fiat 500 to Matteotti square. According to eyewitness accounts by street cleaners working around the Palazzo Ducale there was a sudden bright flash of light in the area at around 3:00 am. At first they did not realise that the flame was a burning man. Only when they approached closer did they see Georgakis burning and running while ablaze shouting, "Long Live Greece", "Down with the tyrants", "Down with the fascist colonels" and "I did it for my Greece."[7][10] The street cleaners added that at first Georgakis refused their help and ran away from them when they tried to extinguish the fire.[10][11] They also said that the smell of burning flesh was something they would never forget and that Georgakis was one in a million.[10]

According to an account by his father who went to Italy after the events, Georgakis's body was completely carbonised from the waist down up to a depth of at least three centimetres in his flesh. Georgakis died nine hours after the events in the square at around 12 noon the same day.[10][12] His last words were: Long Live Free Greece.[13]

Reaction of the junta

The Greek newspaper To Vima in the January 2009 article "The 'return' of Kostas Georgakis" with the subtitle "Even the remains of the student who sacrificed himself for Democracy caused panic to the dictatorship" by Fotini Tomai, supervisor of the historical and diplomatic archives of the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The article reports that throughout the crisis in Italy the Greek consulate sent confidential reports to the junta where it raised fears that the death of Georgakis would be compared to the death of Jan Palach (through express diplomatic letter of 20 September 1970 Greek: ΑΠ 67, εξ. επείγον, 20 Σεπτεμβρίου 1970) and could adversely affect Greek tourism while at the same time it raised concerns that Georgakis's grave would be used for anti-junta propaganda and "anti-nation pilgrimage" and "political exploitation".[7]

Through a diplomatic letter dated 25 August 1972 (ΑΠ 167/ΑΣ 1727, 25 Αυγούστου 1972) Greek consular authorities in Italy reported to the junta in Athens that an upcoming Italian film about Georgakis would seriously damage the junta and it was proposed that the junta take measures through silent third-party intervention to obtain the worldwide distribution rights of the film so that it would not fall into the hands of German, Scandinavian, American stations and the BBC which were reported as interested in obtaining it.[7] The film was scheduled to appear at the "Primo Italiano" festival in Torino, at the festival of Pesaro and the Venice anti-festival under the title "Galani Hora" ("Blue Country"; in Italian, "Uno dei tre"). Gianni Serra was the director and the film was a coproduction by RAI and CTC at a total cost of 80 million Italian lire. The dictatorship was also afraid that the film would create the same anti-junta sentiment as the film Z by Costa-Gavras.[7]

The minister of Foreign Affairs of the junta Xanthopoulos-Palamas in the secret encrypted message ΑΠ ΓΤΛ 400-183 of 26 November 1970 (ΑΠ ΓΤΛ 400-183 απόρρητον κρυπτοτύπημα, 26 Νοεμβρίου 1970) suggests to the Greek consular authorities in Italy to take precautions so that during the loading of the remains on the ship to avoid any noise and publicity.[7] It was clear that the junta did not want a repeat of the publicity that occurred during Georgakis's funeral procession on 22 September 1970 in Italy.[7]

On 22 September 1970 Melina Merkouri led a demonstration of hundreds of flag and banner-waving Italian and Greek anti-junta resistance members during the funeral procession of Georgakis in Italy. Merkouri was holding a bouquet of flowers for the dead hero. According to press reports Greek secret service agents were sent from Greece for the occasion.[7] The number of people at the funeral was estimated at 1,500.[9] In another diplomatic letter it is mentioned that Stathis Panagoulis, brother of Alexandros Panagoulis was scheduled to give the funeral address but did not attend.[7]

According to diplomatic message ΑΠ 432, dated 23 September 1970 (ΑΠ 432, 23 Σεπτεμβρίου 1970) from the Greek Embassy in Rome, then ambassador A. Poumpouras transmitted to the junta that hundreds of workers and anti-junta resistance members accompanied Georgakis's body from the hospital to the mausoleum in Genoa where he was temporarily interred. In the afternoon of the same day a demonstration of about a thousand was held which was organised by leftist parties shouting "anti-Hellenic" and anti-American slogans according to the ambassador. In the press conference which followed the demonstrations Melina Merkouri was scheduled to talk but instead Ioannis Leloudas from Paris and Chistos Stremmenos attended, the latter bearing a message from Andreas Papandreou. According to the ambassador's message Italian police took security precautions around the Greek consulate at the time, at the request of the Greek Embassy in Rome.[7]

Another consular letter by consul N. Fotilas (ΑΠ 2 14 January 1971, ΑΠ 2, 14 Ιανουαρίου 1971) mentioned that on 13 January 1971 the remains of Georgakis were transferred to the ship Astypalaia owned by Vernikos-Eugenides under the Greek flag. The ship was scheduled to leave for Piraeus on 17 January carrying the remains of Georgakis to Greece. With this a series of obstacles, mishaps, adventures and misadventures involving the return of the remains came to an end.[7]

On 18 January 1971, a secret operation was undertaken by the junta to finally bury Georgakis's remains in the municipal cemetery of Corfu city. A single police cruiser accompanied the Georgakis family, who were transported to the cemetery by taxi.[10]

Letters written

Letter to his father

Georgakis wrote a final letter to his father. Newspaper publisher, and owner of Kathimerini, Helen Vlachos, in one of her books, mentions this letter as well.[3][10]

My dear father. Forgive me for this act, without crying. Your son is not a hero. He is a human, like all the others, maybe a little more fearful. Kiss our land for me. After three years of violence I cannot suffer any longer. I don't want you to put yourselves in any danger because of my own actions. But I cannot do otherwise but think and act as a free individual. I write to you in Italian so that I can raise the interest of everyone for our problem. Long Live Democracy. Down with the tyrants. Our land which gave birth to Freedom will annihilate tyranny! If you are able to, forgive me. Your Kostas.

Letter to a friend

In a letter to a friend Georgakis mentions:

I am sure that sooner or later the people of Europe will understand that a fascist regime like the one based on Greek tanks is not only an insult to their dignity as free men but also a constant threat to Europe. ... I do not want my action to be considered heroic as it is nothing more than a situation of no choice. On the other hand, maybe some people will awaken to see what times we live in.[8]

Recognition

The Municipality of Corfu has dedicated a memorial in his honour near his home in Corfu city. His sacrifice was later recognized and honoured by the new democratic Hellenic Government after metapolitefsi.[1]

In his monument a plaque is inscribed with his words in Greek. The monument was created gratis by sculptor Dimitris Korres.[14]

Poet Nikiforos Vrettakos in his poem "I Thea tou Kosmou" (The View of the World) wrote for Georgakis:

...you were the bright summary of our drama...in one and the same torch, the light of the resurrection and our mourning by the gravestone...[15]

Poet Yannis Koutsoheras wrote:[12]

| Original | Translation |

|---|---|

ζωντανός σταυρός φλεγόμενος |

Living cross burning |

On 18 September 2000 in a special all-night event at Matteotti square, Genoa honoured the memory of Georgakis.[16]

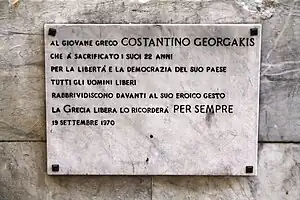

In Matteotti square where he died, a plaque stands with the inscription in Italian: La Grecia Libera lo ricorderà per sempre (Free Greece will remember him forever).[15] The complete inscription on the plaque reads:

Al Giovane Greco Constantino Georgakis che à sacrificato i suoi 22 anni per la Libertà e la Democrazia del suo paese. Tutti gli Uomini Liberi rabbrividiscono davanti al suo Eroico Gesto. La Grecia Libera lo ricorderà per sempre

which translates in English:

To the young Greek Konstantin Georgakis who sacrificed his 22 years for the Freedom and Democracy of his country. All Free Men shudder before his heroic gesture. Free Greece will remember him forever

Legacy

I cannot but think and act as a free individual

— Kostas Georgakis

Georgakis is the only known junta opponent to have killed himself in protest against the junta and he is considered the precursor of the later student protests, such as the Polytechnic uprising.[1] At the time, his death caused a sensation in Greece and abroad as it was the first tangible manifestation of the depth of resistance against the junta. The junta delayed the arrival of his remains to Corfu for four months citing security reasons and fearing demonstrations while presenting bureaucratic obstacles through the Greek consulate and the junta government.[1][8][10][15]

Kostas Georgakis is cited as an example indicating the strong relation between an individual's identity and his/her reasons to continue living.[17] Georgakis' words were cited as an indication that his strong identification as a free individual gave him the reason to end his life.[17]

Film

- Once Upon A Time There Were Heroes, Direction: Andreas Apostolidis, Screenplay: Stelios Kouloglou, Cinematography: Vangelis Koulinos, Created by: Stelios Kouloglou, Production: Lexicon & Partners, BetacamSp Colour 58 minutes.[18][19]

- Reportage without frontiers: documentary Title: "The Georgakis Case" Director: Kostas Kouloglou

- Uno dei tre (1973) Film by Gianni Serra[20]

Books

See also

Citations

- "Story of Kostas in Corfu City Hall website". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2010. [lower-alpha 1]

- Annamaria Rivera (2012). Il fuoco della rivolta. Torce umane dal Maghreb all'Europa. Edizioni Dedalo. p. 118. ISBN 978-88-220-6322-9. Retrieved 15 March 2013.[lower-alpha 2]

- Helen Vlachos (1972). Griechenland, Dokumentation einer Diktatur. Jugend und Volk. ISBN 978-3-7141-7415-1. Retrieved 15 March 2013.[lower-alpha 3]

- Giovanni Pattavina; Oriana Fallaci (1984). Alekos Panagulis, il rivoluzionario don Chisciotte di Oriana Fallaci: saggio politico-letterario. Edizioni italiane di letteratura e scienze. p. 211. Retrieved 10 April 2013.[lower-alpha 4]

- Rivisteria. 2000. p. 119. Retrieved 10 April 2013.[lower-alpha 5]

- Kostis Kornetis (2013). Children of the Dictatorship: Student Resistance, Cultural Politics and the "Long 1960s" in Greece. Berghahn Books. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-78238-001-6.[lower-alpha 6]

- "The "return" of Kostas Georgakis" with the subtitle "Even the remains of the student who sacrificed himself for Democracy caused panic to the dictatorship"". To Vima. 11 January 2009. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012.[lower-alpha 7]

- "CEDOST Centro di documentazione storico politica su stragismo, terrorismo e violenza politica (Historical Documentation Centre on campaigns of violence, terrorism and political violence)". Archived from the original on 4 April 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2008.[lower-alpha 8]

- G. Laschi (2012). Memoria d'Europa. Riflessioni su dittature, autoritarismo, bonapartismo e svolte democratiche. FrancoAngeli. p. 103. ISBN 978-88-568-4704-8. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Kostas Georgakis: The tragic sacrifice which shook the junta" Κώστας Γεωργάκης: Η τραγική θυσία που κλόνισε τη χούντα. (in Greek). Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.[lower-alpha 12]

- Jason Manolopoulos (2011). Greece's 'Odious' Debt: The Looting of the Hellenic Republic by the Euro, the Political Elite and the Investment Community. Anthem Finance Anthem Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780857287717.

- "Georgakis' story". Archived from the original on 21 February 2010.

- Italian book archive[lower-alpha 14]

- "Simerini". Retrieved 6 September 2016.[lower-alpha 9]

- "Kostas Georgakis" Κώστας Γεωργάκης. sansimera.gr. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2023. [lower-alpha 10]

- "The Georgakis Case". Reportage without frontiers. Archived from the original on 30 August 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010. [lower-alpha 11]

- Zillmer, John C. (Michigan State University) (2008). The unity of identity: A defense of an ideal. p. 74. ISBN 9780549844228. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Greek Film Festival". Archived from the original on 15 December 2008. [lower-alpha 13]

- "mia fora ke enan kero ipirchan iroes Andreas Apostolidis Greece". International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam.

- "Uno dei tre – film – Archivio Aamod". Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

Notes

- During the years of dictatorship in Greece (1967–1974) many Corfiots were enlisted in resistance groups, but the case of Kostas Georgakis is unique in the whole of Greece. The 22 year-old Corfiot student of geology with an act of self-sacrifice and a spirit of dynamic protest, which could not bear to see Greece under the military regime, set himself on fire the first morning hours of 19 September 1970 in the Matteoti Sq. in the Italian city of Genoa. For security reasons his body was buried in Corfu four months later, his self-sacrifice though, a rare event for that time, caused international sensation and was considered as one of the most important resistance acts of that period. Later the Hellenic State and his homeland Corfu honoured the man, who with his life became a symbol of resistance and patriotism, herald of the students' sacrifice in Polytechnion in 1973

- [L]o studente di geologia Kostas Georgakis, oppositore greco di cultura laica, esasperato dalle minacce e dalle rappresaglie subite da agenti dei servizi segreti greci in Italia, s'immolò in piazza Matteotti per protestare contro la giunta dei Colonnelli.

- Chapter: In memoriam Kostas Georgakis Er starb für die Freiheit Griechenlands so wie Jan Palach für die der Tschechoslowakei Lieber Vater, verzeih mir diese Tat und weine nicht. Dein Sohn ist kein Held, er ist ein Mann wie alle anderen, vielleicht nur etwas ängstlicher.

- Uno di questi fu lo studente greco Kostas Georgakis, un ragazzo di 22 anni che il 29 settembre 1970 si bruciò vivo a Genova per protestare contro la soppressione della libertà in Grecia. La sera del suo sacrificio riaccompagnò a casa la fidanzata.

- Il suicidio del giovane studente greco Kostas Georgakis in sacrificio alla propria patria nel nome di libertà e democrazia apre una finestra su trent'anni di storia ...

- In 1971 at the Piazza Matteotti in Genova, the young student Kostas Georgakis set himself ablaze in protest against the Colonels ... a Panteios student and present-day political scientist, recalls how he suffered when Georgakis died, being inspired by his action ...

- Article by Fotini Tomai supervisor of the historical and diplomatic archives of the Greek Foreign Ministry 11 January 2009 (Greek: IΑΝΟΥΑΡΙΟΣ 1971 Η «επιστροφή» του Κώστα ΓεωργάκηΑκόμη και η σορός του φοιτητή που θυσιάστηκε για τη δημοκρατία προκαλούσε πανικό στη δικτατορία ΦΩΤΕΙΝΗ ΤΟΜΑΗ)

(ΑΠ ΓΤΛ 400-183, απόρρητον κρυπτοτύπημα, 26 Νοεμβρίου 1970). χούντας υπουργός Εξωτερικών Ξανθόπουλος-Παλαμάς, μόλις δύο μήνες αργότερα, συνιστώντας «ευαρεστηθήτε μεριμνήσητε όπως κατά μεταφοράν και φόρτωσιν σορού επί πλοίου αποφευχθή πας θόρυβος και δημοσιότης» (ΑΠ ΓΤΛ 400-183, απόρρητον κρυπτοτύπημα, 26 Νοεμβρίου 1970). " and "Εν μέσω πλήθους Ιταλών και ελλήνων αντιστασιακών οι οποίοι συνοδεύουν με σημαίες και λάβαρα τη νεκρώσιμη πομπή του Γεωργάκη, η Μελίνα Μερκούρη κρατώντας ανθοδέσμη για τον νεκρό ήρωα. Ανάμεσά τους, σύμφωνα με δημοσιεύματα του Τύπου, υπήρχαν αρκετοί μυστικοί πράκτορες σταλμένοι από την Ελλάδα

...

εκατοντάς φοιτητών και εργατών συνώδευσαν νεκρόν από νοσοκομείου μέχρι νεκρικού θαλάμου νεκροταφείου ένθα εναπετέθη. Συμμετέσχε και αριστερός Υποδήμαρχος Γενούης Geroflini.Απόγευμα αυτής ημέρας έλαβε χώραν προαγγελθείσα και οργανωθείσα υπό αριστερών κομμάτων διαδήλωσις.Συμμετέσχον περίπου χίλιοι με συνθήματα κατ΄ αρχήν ανθελληνικά και εν συνεχεία αντικομμουνιστικά αντιαμερικανικά. Εις συνέντευξιν Τύπου ην επρόκειτο δώση Μερκούρη,παρέστησαν αντ΄ αυτής οι Ιωάννης Λελούδας εκ Παρισίων και Χρίστος Στρεμμένος, όστις και εκόμισε μήνυμα του Α. Παπανδρέου. Κατόπιν ημετέρων ενεργειών,αστυνομία είχε λάβει ικανά μέτρα προστασίας εισόδου Προξενείου» and "σύμφωνα με πληροφορίες της προξενικής ελληνικής αρχής στη Βενετία, ετοιμαζόταν να προβληθεί στο φεστιβάλ Ρrimo Ιtaliano (Τορίνο), στο φεστιβάλ του Ρesaro και στο αντιφεστιβάλ Βενετίας ταινία με τίτλο «Γαλανή χώρα» («Ρaese azzurro») του σκηνοθέτη Τζιάνι Σέρα, συμπαραγωγή της RΑΙ ΤV και της εταιρείας CΤC, συνολικής δαπάνης 80 εκατομμυρίων λιρετών Ιταλίας, με σενάριο βασισμένο στη ζωή και το τέλος του Γεωργάκη και πολύ μικρές παραλλαγές." also "Σε άλλο τηλεγράφημα γινόταν μνεία του γεγονότος ότι δεν παρέστη τελικώς ο αδελφός τού Αλέκου Παναγούλη Στάθης, που είχε αρχικώς αναγγελθεί ότι επρόκειτο να εκφωνήσει τον επικήδειο. Ωστόσο η σορός του άτυχου νέου θα παραμείνει επί τετράμηνο στον νεκροθάλαμο του νεκροταφείου της Γένοβας και ύστερα από χρονοβόρα διαδικασία θα φορτωθεί εν μέσω περιπετειών στις 13 Ιανουαρίου 1971 στο υπό ελληνική σημαία πλοίο «Αστυπάλαια», πλοιοκτησίας Βερνίκου-Ευγενίδη, το οποίο, σύμφωνα με τον πρόξενο Κ. Φωτήλα, υπολογιζόταν να καταπλεύσει στον Πειραιά το μεσημέρι της 17ης Ιανουαρίου (ΑΠ 2, 14 Ιανουαρίου 1971). - Translation via Google: Kosta Georgakis attended the University of Genoa and in 1968 he had enrolled in the Ek-Edin (Greek Democratic Youth) body of the Union of the Center to which Alexandros Panagoulis and Andreas Papandreou belonged, among others. His impatience with the dictatorship of the colonels led him to release an interview on 26 July 1970 with a Genoese periodical, signa a, in which, anonymously, he not only denounced the crimes of the dictatorship, but made public the news that some people, posing as students, they had formed an association called Esesi (National League of Greek students in Italy), with offices in the main Italian university cities, which worked for the Greek secret services (Kyp) registering and denouncing democratic students. It also highlighted the link between the colonels and some far-right Italian soldiers and politicians, documented since 1969.

The recording of this interview reached the Greek Consulate where Kostas was recognized and a few days later he was presumably attacked by one of the Esesi members.

Political activity in an anti-dictatorial sense usually had repercussions on the families who remained in Greece and Georgakis was very worried about this. He therefore decided that the only significant gesture he could make, without causing retaliation, was to burn himself and he did so shouting "Long live free Greece" on September 19, 1970 in Piazza Matteotti.

He wrote to a friend: I am sure that sooner or later the peoples of Europe will understand that a fascist regime like the Greek one based on tanks is not only an offense to their dignity as free men but also a continuous threat to Europe. ... I don't want this action of mine to be considered heroic as it is nothing more than a no-choice situation. On the other hand it will perhaps awaken some people to whom it will show the times we live in. (C. Paputsis, The big one, The Kostas Georgakis case, Genoa, Erga Edizioni).

For four months his remains remained unburied due to the bureaucratic obstacles that the Consulate and the Greek Government opposed to transport to Corfu.) - Memory of a brave lad. Thursday 11 September 2008. (Μνήμη ενός γενναίου παλικαριού ΡΕΠΟΡΤΑΖ: Κώστας Σπηλιωτόπουλος Πέμπτη 11 Σεπ 2008)

- Ο μεγάλος μας ποιητής Νικηφόρος Βρεττάκος απαθανάτισε τη θυσία του με τους στίχους από το ποίημά του «Η Θέα του Κόσμου»: «…ήσουν η φωτεινή περίληψη του δράματός μας…στην ίδια λαμπάδα τη μία, τ' αναστάσιμο φως κι ο επιτάφιος θρήνος μας…»" "Στο σημείο της θυσίας υπάρχει σήμερα μια μαρμάρινη στήλη με την επιγραφή στα ιταλικά: «Η Ελλάδα θα τον θυμάται για πάντα». Η Χούντα αποσιώπησε το γεγονός κι επέτρεψε τη μεταφορά της σορού του στη γενέτειρά του με καθυστέρηση τεσσάρων μηνών, φοβούμενη τη λαϊκή αντίδραση. Η πράξη του αφύπνισε τη διεθνή κοινή γνώμη για την κατάσταση στην Ελλάδα, που στέναζε κάτω από την μπότα των Συνταγματαρχών.

- Τίτλος : ΥΠΟΘΕΣΗ ΓΕΩΡΓΑΚΗ Θέμα : ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΑ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΚΑ Τριάντα χρόνια μετά, στις 18 Σεπτεμβρίου του 2000, η Γένοβα ξενύχτησε. Στο κέντρο της πόλης, στην πλατεία Ματεότι, έγινε μια ειδική εκδήλωση αφιερωμένη στον Κώστα Γεωργάκη.Το ντοκιμαντέρ του Στέλιου Κούλογλου φέρνει στην επιφάνεια μια υπόθεση η οποία ακόμη και μετά την πτώση της δικτατορίας έμεινε για πολλά χρόνια στο αρχείο.

- Αγαπημένε μου πατέρα. Συγχώρεσέ μου αυτή την πράξη, χωρίς να κλάψεις. Ο γιος σου δεν είναι ένας ήρωας. Είναι ένας άνθρωπος, όπως οι άλλοι, ίσως με λίγο φόβο παραπάνω. Φίλησε τη γη μας για μένα. Μετά από τρία χρόνια βίας δεν αντέχω άλλο. Δε θέλω εσείς να διατρέξετε κανέναν κίνδυνο, εξαιτίας των δικών μου πράξεων. Αλλά εγώ δεν μπορώ να κάνω διαφορετικά παρά να σκέπτομαι και να ενεργώ σαν ελεύθερο άτομο. Σου γράφω στα ιταλικά για να προκαλέσω αμέσως το ενδιαφέρον όλων για το πρόβλημά μας. Ζήτω η Δημοκρατία. Κάτω οι τύραννοι. Η γη μας που γέννησε την ελευθερία θα εκμηδενίσει την τυραννία! Εάν μπορείτε, συγχωρέστε με. Ο Κώστας σου.

- Costas Georgakis was a student at the University of Genoa in Italy. On 18 September 1970, Georgakis, then barely 22 years old, chose death by self-immolation, in order to protest the dictatorship in Greece. Although his act was concealed by the Greek state, it aroused international public opinion and turned the world's attention to Greece's military regime. This documentary reconstructs the main facets of the life of Costas Georgakis, his childhood and adolescence in Corfu, his spiritual and political concerns, his participation in the struggle against the dictatorship, his decision to sacrifice his life in an ultimate act of protest against the dictatorship. People who knew Georgakis are interviewed, including his family, his childhood friends, his professors, his comrades in the resistance movement, but also Genovese, for whom Georgakis is a part of history and a symbol of democracy. This film was screened to an audience of students from the University of Athens, who are the same age as Georgakis was when he made the big decision, and their reactions were also filmed. How do the young people of today view Georgakis' act? Do they consider it useless or pointless? For which issues would they be prepared to sacrifice their own lives?

- [L]a storia del ventiduenne greco che nel settembre del 1970 si diede fuoco in piazza Matteotti a Genova al grido di "Viva la Grecia libera". Era iscritto al terzo anno di Geologia all'università di Genova.

Translation by Google: The story of the 22 year old Greek who in September 1970 set himself on fire in Piazza Matteotti in Genoa shouting "Long live free Greece." He was enrolled in the third year of Geology at the University of Genoa

External links

- Story of Kostas on the website of the Corfu City Hall

- "Italian website with tribute to Kostas Georgakis". Archived from the original on 4 April 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2008.