Kūkai

Kūkai (空海; 27 July 774 – 22 April 835[1]), born Saeki no Mao (佐伯 眞魚),[2] posthumously called Kōbō Daishi (弘法大師, "The Grand Master who Propagated the Dharma"), was a Japanese Buddhist monk, calligrapher, and poet who founded the esoteric Shingon school of Buddhism. He travelled to China, where he studied Tangmi (Chinese Vajrayana Buddhism) under the monk Huiguo. Upon returning to Japan, he founded Shingon—the Japanese branch of Vajrayana Buddhism. With the blessing of several Emperors, Kūkai was able to preach Shingon teachings and found Shingon temples. Like other influential monks, Kūkai oversaw public works and constructions. Mount Kōya was chosen by him as a holy site, and he spent his later years there until his death in 835 C.E.

Kūkai | |

|---|---|

空海 | |

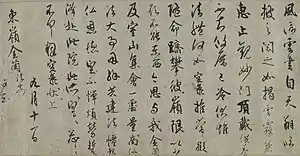

Painting of Kūkai from the Shingon Hassozō, a set of scrolls depicting the first eight patriarchs of the Shingon school. Japan, Kamakura period (13th-14th centuries). | |

| Title | Founder of Shingon Buddhism |

| Personal | |

| Born | 27 July 774 (15th day, 6th month, Hōki 5)[1] |

| Died | 22 April 835 (age 60) (21st day, 3rd month, Jōwa 2)[1] |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Vajrayana Buddhism, Shingon |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Huiguo |

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism in Japan |

|---|

|

Because of his importance in Japanese Buddhism, Kūkai is associated with many stories and legends. One such legend attribute the invention of the kana syllabary to Kūkai, with which the Japanese language is written to this day (in combination with kanji), as well as the Iroha poem, which helped to standardise and popularise kana.[3]

Shingon followers usually refer to Kūkai by the honorific title of Odaishi-sama (お大師様, "The Grand Master"), and the religious name of Henjō Kongō (遍照金剛, "Vajra Shining in All Directions").

Biography

Early years

Kūkai was born in 774 in the precinct of Zentsū-ji temple, in Sanuki province on the island of Shikoku. His family were members of the aristocratic Saeki family, a branch of the ancient Ōtomo clan. In modern scholarship, his first name is generally believed to be Mao ("True Fish"),[5] although one source records his birth name as Tōtomono ("Precious One"). Kūkai was born in a period of important political changes with Emperor Kanmu (r. 781–806) seeking to consolidate his power and to extend his realm, taking measures which included moving the capital of Japan from Nara ultimately to Heian (modern-day Kyoto).

Little more is known about Kūkai's childhood. At the age of fifteen, he began to receive instruction in the Chinese classics under the guidance of his maternal uncle. During this time, the Saeki-Ōtomo clan suffered government persecution due to allegations that the clan chief, Ōtomo Yakamochi, was responsible for the assassination of his rival Fujiwara no Tanetsugu.[5] The family fortunes had fallen by 791 when Kūkai journeyed to Nara, the capital at the time, to study at the government university, the Daigakuryō (大学寮). Graduates were typically chosen for prestigious positions as bureaucrats. Biographies of Kūkai suggest that he became disillusioned with his Confucian studies, but developed a strong interest in Buddhist studies instead.

Around the age of 22, Kūkai was introduced to Buddhist practice involving chanting the mantra of Kokūzō (Sanskrit: Ākāśagarbha), the bodhisattva of the void. During this period, Kūkai frequently sought out isolated mountain regions where he chanted the Ākāśagarbha mantra relentlessly. At age 24 he published his first major literary work, Sangō Shiiki, in which he quotes from an extensive list of sources, including the classics of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. The Nara temples, with their extensive libraries, possessed these texts.

During this period in Japanese history, the central government closely regulated Buddhism through the Sōgō (僧綱, Office of Priestly Affairs) and enforced its policies, based on the ritsuryō legal code. Ascetics and independent monks, like Kūkai, were frequently banned and lived outside the law, but still wandered the countryside or from temple to temple.[6]

During this period of private Buddhist practice, Kūkai had a dream, in which a man appeared and told Kūkai that the Mahavairocana Tantra is the scripture which contained the doctrine Kūkai was seeking.[5] Though Kūkai soon managed to obtain a copy of this sutra which had only recently become available in Japan, he immediately encountered difficulty. Much of the sutra was in untranslated Sanskrit written in the Siddhaṃ script. Kūkai found the translated portion of the sutra was very cryptic. Because Kūkai could find no one who could elucidate the text for him, he resolved to go to China to study the text there. Ryuichi Abe suggests that the Mahavairocana Tantra bridged the gap between his interest in the practice of religious exercises and the doctrinal knowledge acquired through his studies.[6]

Travel and study in China

In 804, Kūkai took part in a government-sponsored expedition to China, led by Fujiwara no Kadanomaro, in order to learn more about the Mahavairocana Tantra. Scholars are unsure why Kūkai was selected to take part in an official mission to China, given his background as a private monk who was not sponsored by the state. Theories include family connections within the Saeki-Ōtomo clan, or connections through fellow clergy or a member of the Fujiwara clan.[5]

The expedition included four ships, with Kūkai on the first ship, while another famous monk, Saichō was on the second ship. During a storm, the third ship turned back, while the fourth ship was lost at sea. Kūkai's ship arrived weeks later in the province of Fujian and its passengers were initially denied entry to the port while the ship was impounded. Kūkai, being fluent in Chinese, wrote a letter to the governor of the province explaining their situation.[7] The governor allowed the ship to dock, and the party was asked to proceed to the capital of Chang'an (present day Xi'an), the capital of the Tang dynasty.

After further delays, the Tang court granted Kūkai a place in Ximing Temple, where his study of Chinese Buddhism began in earnest. He also studied Sanskrit with the Gandharan pandit Prajñā (734–810?), who had been educated at the Indian Buddhist university at Nalanda.

It was in 805 that Kūkai finally met the monk Huiguo (746–805) the man who would initiate him into Chinese Esoteric Buddhism (Tangmi) at Chang'an's Qinglong Monastery (青龍寺). Huiguo came from an illustrious lineage of Buddhist masters, famed especially for translating Sanskrit texts into Chinese, including the Mahavairocana Tantra. Kūkai describes their first meeting:

Accompanied by Jiming, Tansheng, and several other Dharma masters from the Ximing monastery, I went to visit him [Huiguo] and was granted an audience. As soon as he saw me, the abbot smiled, and said with delight, "since learning of your arrival, I have waited anxiously. How excellent, how excellent that we have met today at last! My life is ending soon, and yet I have no more disciples to whom to transmit the Dharma. Prepare without delay the offerings of incense and flowers for your entry into the abhisheka mandala".[6]

Huiguo immediately bestowed upon Kūkai the first level abhisheka (esoteric initiation). Whereas Kūkai had expected to spend 20 years studying in China, in a few short months he was to receive the final initiation, and become a master of the esoteric lineage. Huiguo was said to have described teaching Kūkai as like "pouring water from one vase into another".[6] Huiguo died shortly afterwards, but not before instructing Kūkai to return to Japan and spread the esoteric teachings there, assuring him that other disciples would carry on his work in China.

Kūkai arrived back in Japan in 806 as the eighth Patriarch of Esoteric Buddhism, having learnt Sanskrit and its Siddhaṃ script, studied Indian Buddhism, as well as having studied the arts of Chinese calligraphy and poetry, all with recognized masters. He also arrived with a large number of texts, many of which were new to Japan and were esoteric in character, as well as several texts on the Sanskrit language and the Siddhaṃ script.

However, in Kūkai's absence Emperor Kanmu had died and was replaced by Emperor Heizei who exhibited no great enthusiasm for Buddhism. Kūkai's return from China was eclipsed by Saichō, the founder of the Tendai school, who found favor with the court during this time. Saichō had already had esoteric rites officially recognised by the court as an integral part of Tendai, and had already performed the abhisheka, or initiatory ritual, for the court by the time Kūkai returned to Japan. Later, with Emperor Kanmu's death, Saichō's fortunes began to wane.

Saichō requested, in 812, that Kūkai give him the introductory initiation, which Kūkai agreed to do. He also granted a second-level initiation upon Saichō, but refused to bestow the final initiation (which would have qualified Saichō as a master of esoteric Buddhism) because Saichō had not completed the required studies, leading to a falling out between the two that was not resolved; this feud later extended to the Shingon and Tendai sects.

Little is known about Kūkai's movements until 809 when the court finally responded to Kūkai's report on his studies, which also contained an inventory of the texts and other objects he had brought with him, and a petition for state support to establish the new esoteric Buddhism in Japan. That document, the Catalogue of Imported Items, is the first attempt by Kūkai to distinguish the new form of Buddhism from that already practiced in Japan. The court's response was an order to reside in Takao-san temple (modern Jingo-ji) in the suburbs of Kyoto. This was to be Kūkai's headquarters for the next 14 years. The year 809 also saw the retirement of Emperor Heizei due to illness and the succession of the Emperor Saga, who supported Kūkai and exchanged poems and other gifts.

Emerging from obscurity

In 810, Kūkai emerged as a public figure when he was appointed administrative head of Tōdai-ji, the central temple in Nara, and head of the Sōgō (僧綱, Office of Priestly Affairs).

Shortly after his enthronement, Emperor Saga became seriously ill, and while he was recovering, Emperor Heizei fomented a rebellion, which had to be put down by force. Kūkai petitioned the Emperor to allow him to carry out certain esoteric rituals which were said to "enable a king to vanquish the seven calamities, to maintain the four seasons in harmony, to protect the nation and family, and to give comfort to himself and others". The petition was granted. Prior to this, the government relied on the monks from the traditional schools in Nara to perform rituals, such as chanting the Golden Light Sutra to bolster the government, but this event marked a new reliance on the esoteric tradition to fulfill this role.

With the public initiation ceremonies for Saichō and others at Takao-san temple in 812, Kūkai became the acknowledged master of esoteric Buddhism in Japan. He set about organizing his disciples into an order – making them responsible for administration, maintenance and construction at the temple, as well as for monastic discipline. In 813 Kūkai outlined his aims and practices in the document called The admonishments of Konin. It was also during this period at Takaosan that he completed many of the seminal works of the Shingon School:

- Attaining Enlightenment in This Very Existence

- The Meaning of Sound, Word, Reality

- Meanings of the Word Hūm

All of these were written in 817. Records show that Kūkai was also busy writing poetry, conducting rituals, and writing epitaphs and memorials on request. His popularity at the court only increased, and spread.

Meanwhile, Kukai's new esoteric teachings and literature drew scrutiny from a noted scholar-monk of the time named Tokuitsu, who traded letters back and forth in 815 asking for clarification. The dialogue between them proved constructive and helped to give Kūkai more credibility, while the Nara Schools took greater interest in esoteric practice.[9]

Mount Kōya

In 816, Emperor Saga accepted Kūkai's request to establish a mountain retreat at Mount Kōya as a retreat from worldly affairs. The ground was officially consecrated in the middle of 819 with rituals lasting seven days. He could not stay, however, as he had received an imperial order to act as advisor to the secretary of state, and he therefore entrusted the project to a senior disciple. As many surviving letters to patrons attest, fund-raising for the project now began to take up much of Kūkai's time, and financial difficulties were a persistent concern; indeed, the project was not fully realised until after Kūkai's death in 835.

Kūkai's vision was that Mt. Kōya was to become a representation of the Mandala of the Two Realms that form the basis of Shingon Buddhism: the central plateau as the Womb Realm mandala, with the peaks surrounding the area as petals of a lotus; and located in the centre of this would be the Diamond Realm mandala in the form of a temple which he named Kongōbu-ji ("Diamond Peak Temple"). At the center of the temple complex sits an enormous statue of Vairocana, who is the personification of Ultimate Reality.

Public works

In 821, Kūkai took on a civil engineering task, that of restoring Manno Reservoir, which is still the largest irrigation reservoir in Japan.[10] His leadership enabled the previously floundering project to be completed smoothly, and is now the source of some of the many legendary stories which surround his figure. In 822 Kūkai performed an initiation ceremony for the ex-emperor Heizei. In the same year Saichō died.

Tō-ji Period

When Emperor Kanmu had moved the capital in 784, he had not permitted the powerful Buddhists from the temples of Nara to follow him. He did commission two new temples: Tō-ji (Eastern Temple) and Sai-ji (Western Temple) which flanked the road at southern entrance to the city, protecting the capital from evil influences. However, after nearly thirty years the temples were still not completed. In 823 the soon-to-retire Emperor Saga asked Kūkai, experienced in public works projects, to take over Tō-ji and finish the building project. Saga gave Kūkai free rein, enabling him to make Tō-ji the first Esoteric Buddhist centre in Kyoto, and also giving him a base much closer to the court, and its power.

The new emperor, Emperor Junna (r. 823–833) was also well disposed towards Kūkai. In response to a request from the emperor, Kūkai, along with other Japanese Buddhist leaders, submitted a document which set out the beliefs, practices and important texts of his form of Buddhism. In his imperial decree granting approval of Kūkai's outline of esoteric Buddhism, Junna uses the term Shingon-shū (真言宗, Mantra Sect) for the first time. An imperial decree gave Kūkai exclusive use of Tō-ji for the Shingon School, which set a new precedent in an environment where previously temples had been open to all forms of Buddhism. It also allowed him to retain 50 monks at the temple and train them in Shingon. This was the final step in establishing Shingon as an independent Buddhist movement, with a solid institutional basis with state authorization. Shingon had become legitimate.

In 824, Kūkai was officially appointed to the temple construction project. In that year he founded Zenpuku-ji, the second oldest temple of the Edo (Tokyo) region. In 824 he was also appointed to the Office of Priestly Affairs. The Office consisted of four positions, with the Supreme Priest being an honorary position which was often vacant. The effective head of the Sōgō was the Daisōzu (大僧都, Senior Director). Kūkai's appointment was to the position of Shōsōzu (小僧都, Junior Director).[6] In addition there was a Risshi (律師, Vinaya Master) who was responsible for the monastic code of discipline. At Tō-ji, in addition to the main hall (kondō) and some minor buildings on the site, Kūkai added the lecture hall in 825 which was specifically designed along Shingon Buddhist principles, which included the making of 14 Buddha images. Also in 825, Kūkai was invited to become tutor to the crown prince. Then in 826 he initiated the construction of a large pagoda at Tō-ji which was not completed in his lifetime (the present pagoda was built in 1644 by the third Tokugawa Shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu). In 827 Kūkai was promoted to be Daisōzu in which capacity he presided over state rituals, the emperor and the imperial family.

The year 828 saw Kūkai open his School of Arts and Sciences (Shugei Shuchi-in). The school was a private institution open to all regardless of social rank. This was in contrast to the only other school in the capital which was only open to members of the aristocracy. The school taught Taoism and Confucianism, in addition to Buddhism, and provided free meals to the pupils. The latter was essential because the poor could not afford to live and attend the school without it. The school closed ten years after Kūkai's death, when it was sold in order to purchase some rice fields for supporting monastic affairs.

Final years

Kūkai completed his magnum opus, The Jūjūshinron (十住心論, Treatise on The Ten Stages of the Development of Mind) in 830. Because of its great length, it has yet to have been fully translated into any language. A simplified summary, Hizō Hōyaku (秘蔵宝鑰, The Precious Key to the Secret Treasury) followed soon after. The first signs of the illness that would eventually lead to Kūkai's death appeared in 831. He sought to retire, but the emperor would not accept his resignation and instead gave him sick leave. Toward the end of 832, Kūkai went back to Mt. Kōya and spent most of his remaining life there. In 834, he petitioned the court to establish a Shingon chapel in the palace for the purpose of conducting rituals that would ensure the health of the state. This request was granted and Shingon ritual became incorporated into the official court calendar of events. In 835, just two months before his death, Kūkai was finally granted permission to annually ordain three Shingon monks at Mt. Kōya – the number of new ordainees being still strictly controlled by the state. This meant that Kōya had gone from being a private institution to a state-sponsored one.

With the end approaching, he stopped taking food and water, and spent much of his time absorbed in meditation. At midnight on the 21st day of the third month (835), he died at the age of 62.[11] Emperor Ninmyō (r. 833–50) sent a message of condolence to Mount Kōya, expressing his regret that he could not attend the cremation due to the time lag in communication caused by Mount Kōya's isolation. However, Kūkai was not given the traditional cremation, but instead, in accordance with his will, was entombed on the eastern peak of Mount Kōya. "When, some time after, the tomb was opened, Kōbō-Daishi was found as if still sleeping, with complexion unchanged and hair grown a bit longer."[12]

Legend has it that Kūkai has not died, but entered into an eternal samadhi (meditative trance) and is still alive on Mount Kōya, awaiting the appearance of Maitreya, the Buddha of the future.[12][13]

Stories and legends

Kūkai's prominence in Japanese Buddhism has spawned numerous stories and legends about him. When searching for a place on Mount Kōya to build a temple, Kūkai was said to have been welcomed by two Shinto deities of the mountain—the male Kariba, and the female Niu. Kariba was said to have appeared as a hunter, and guided Kūkai through the mountains with the help of a white dog and a black dog. Later, both Kariba and Niu were interpreted as manifestations of the Buddha Vairocana, the central figure in Shingon Buddhism and subject of Kūkai's lifelong interest.[14]

Another legend tells the story of Emon Saburō, the wealthiest man in Shikoku. One day, a mendicant monk came to his house, seeking alms. Emon refused, broke the pilgrim's begging bowl, and chased him away. After this, his eight sons fell ill and died. Emon realized that Kūkai was the affronted pilgrim and set out to seek his forgiveness. Having traveled round the island twenty times clockwise in vain, he undertook the route in reverse. Finally, he collapsed exhausted and on his deathbed. Kūkai appeared to grant absolution. Emon requested that he be reborn into a wealthy family in Matsuyama so that he might restore a neglected temple. Dying, he clasped a stone. Shortly afterwards a baby was born with his hand grasped tightly around a stone inscribed "Emon Saburō is reborn." When the baby grew up, he used his wealth to restore the Ishite-ji (石手寺, "Stone-hand Temple"), in which there is an inscription from 1567 recounting the tale.[15][16]

According to one legend, male same-sex love was introduced into Japan by Kūkai. Historians however, point that this is probably not true, since Kūkai was an enthusiastic follower of monastic regulations.[17] Nonetheless, the legend served to "affirm same-sex relation between men and boys in 17th century Japan."[17]

In popular culture

Kūkai (空海) a film from 1984 directed by Junya Sato. Kūkai is played by Kin'ya Kitaōji and Saichō is played by Gō Katō.

The 1991 drama film Mandala (Chinese: 曼荼羅; Japanese: 若き日の弘法大師・空海), a China-Japan co-production, was based on Kūkai's travels in China. The film stars Toshiyuki Nagashima as Kūkai, also co-starring Junko Sakurada and Zhang Fengyi as Huiguo.

The 2017 fantasy film Legend of the Demon Cat stars Shōta Sometani as Kūkai.

Gallery

Statue at Shitennō-ji temple

Statue at Shitennō-ji temple Statue at Jizō-ji temple

Statue at Jizō-ji temple Statue at Kajū-ji temple

Statue at Kajū-ji temple Statue in Nobeoka, Miyazaki

Statue in Nobeoka, Miyazaki Altar at Daisho-in temple, on the island of Miyajima

Altar at Daisho-in temple, on the island of Miyajima

- Outside Japan

Statue of Kūkai in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles

Statue of Kūkai in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles

- Others

The Siddhaṃ alphabet in Kūkai's handwriting. 1837 reproduction by the monk Sōgen.

The Siddhaṃ alphabet in Kūkai's handwriting. 1837 reproduction by the monk Sōgen.

See also

References

- Kūkai was born in 774, the 5th year of the Hōki era; his exact date of birth was designated as the fifteenth day of the sixth month of the Japanese lunar calendar, some 400 years later, by the Shingon sect (Hakeda, 1972 p. 14). Accordingly, Kūkai's birthday is commemorated on June 15 in modern times. This lunar date converts to 27 July 774 in the Julian calendar, and, being an anniversary date, is not affected by the switch to the Gregorian calendar in 1582. Similarly, the recorded date of death is the second year of the Jōwa era, on the 21st day of the third lunar month (Hakeda, 1972 p. 59), i.e. 22 April 835.

- "弘法大師の誕生と歴史". 高野山真言宗 総本山金剛峯寺. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

- Ryūichi Abe (2000). The Weaving of Mantra: Kūkai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. Columbia University Press. pp. 3, 113–4, 391–3. ISBN 978-0-231-11287-1.

- Kobo Daishi (Kukai) as a Boy (Chigo Daishi) - Art Institute of Chicago

- Hakeda, Yoshito S. (1972). Kūkai and His Major Works. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-05933-6.

- Abe, Ryuichi (1999). The Weaving of Mantra: Kukai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11286-4.

- Matsuda, William, J. (2003). The Founder Reinterpreted: Kukai and Vraisemblant Narrative, Thesis, University of Hawai´i, pp. 39-40. Internet Archive

- Singer, R. (1998). Edo - Art in Japan, 1615-1868. National Gallery of Art. p. 37.

- Abe, Ryuichi (1999). The Weaving of Mantra: Kūkai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. Columbia University Press. pp. 206–219. ISBN 978-0-231-11286-4.

- Mogi, Aiichiro (1 January 2007). "A Missing Link: Transfer of Hydraulic Civilization from Sri Lanka to Japan".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Brown, Delmer et al. (1979). Gukanshō, p. 284.

- Casal, U. A. (1959), The Saintly Kōbō Daishi in Popular Lore (A.D. 774-835); Asian Folklore Studies 18, p. 139 (hagiography)

- Yusen Kashiwahara, Koyu Sonoda "Shapers of Japanese Buddhism", Kosei Pub. Co. 1994. "Kukai"

- The Four Deities of Kōyasan Temple Complex. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Reader, Ian (2005). Making Pilgrimages: Meaning and Practice in Shikoku. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 60f. ISBN 978-0-8248-2907-0.

- Miyata, Taisen (2006). The 88 Temples of Shikoku Island, Japan. Koyasan Buddhist Temple, Los Angeles. pp. 102f.

- Schalow, Paul Gordon. "Kukai and the Tradition of Male Love in Japanese Buddhism," in Cabezon, Jose Ignacio, Ed., Buddhism, Sexuality & Gender, State University of New York. p. 215.

Additional sources

- Clipston, Janice (2000). Sokushin-jōbutsu-gi: Attaining Enlightenment in This Very Existence, Buddhist Studies Reviews 17 (2), 207-220

- Giebel, Rolf W.; Todaro, Dale A.; trans. (2004). Shingon texts, Berkeley, Calif.: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research

- Hakeda Yoshito. 1972. Kūkai – Major Works. New York, USA: Columbia University Press.

- Inagaki Hisao (1972). "Kukai's Sokushin-Jobutsu-Gi" (Principle of Attaining Buddhahood with the Present Body), Asia Major (New Series) 17 (2), 190-215

- Skilton, A. 1994. A Concise History of Buddhism. Birmingham: Windhorse Publications.

- Wayman, A and Tajima, R. 1998 The Enlightenment of Vairocana. Delhi: Motilal Barnasidass [includes Study of the Vairocanābhisambodhitantra (Wayman) and Study of the Mahāvairocana-Sūtra (Tajima)].

- White, Kenneth R. 2005. The Role of Bodhicitta in Buddhist Enlightenment. New York: The Edwin Mellen Press (includes Bodhicitta-śāstra, Benkenmitsu-nikyōron, Sanmaya-kaijō)

External links

- Koyosan Shingon Buddhism Kūkai officially founded the seminary community

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Bridge of dreams: the Mary Griggs Burke collection of Japanese art, a catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Kūkai (see index)