A Page of Madness

A Page of Madness (狂った一頁, Kurutta Ichipeiji) is a 1926 Japanese silent experimental horror film directed by Teinosuke Kinugasa. Lost for 45 years until it was rediscovered by Kinugasa in his storehouse in 1971,[3][4] the film is the product of an avant-garde group of artists in Japan known as the Shinkankakuha (or School of New Perceptions) who tried to overcome naturalistic representation.[5][6][7] The film is set in a mental institution in contemporary Japan.

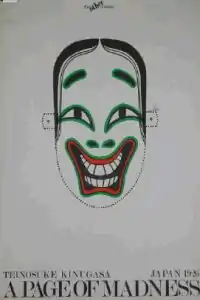

| A Page of Madness | |

|---|---|

Promotional release poster | |

| Directed by | Teinosuke Kinugasa |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Teinosuke Kinugasa |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Kōhei Sugiyama Eiji Tsuburaya[1] |

| Music by | Minoru Muraoka ("New Sound" version) |

Production companies |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 71 minutes[2] |

| Country | Japan |

Yasunari Kawabata, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1968, was credited on the film with the original story. He is often cited as the screenwriter,[8] and a version of the scenario is printed in his complete works, but the scenario is now considered a collaboration between him, Kinugasa, Banko Sawada, and Minoru Inuzuka.[9] Eiji Tsuburaya is credited as an assistant cameraman.[10]

Plot

The film takes place in an asylum in the countryside. Amid a torrential rainstorm, a janitor wanders through the halls revealing the various patients with mental illnesses. The next day, a young woman arrives and is surprised to see her father, the janitor, working there. Her mother is an inmate in the asylum and had gone insane due to the cruelty of her husband, the janitor, when he was a sailor. The husband, feeling guilty, took a job at the asylum to care for her. The daughter announces that she is soon to marry a fine young man, but the janitor begins to worry due to the then-common belief that mental illness was inherited. If the young man's family were to learn of the mother's illness, the marriage might be called off.

At work the janitor's relationship with his wife, unknown to the asylum, interferes with his job. He gets into a fight with some male inmates when his wife is hit, and he is sternly scolded by the head doctor. These events cause the janitor to experience a number of fantasies as he slowly loses control of the border between dreams and reality. He first has a daydream about winning a chest of drawers in a lottery that he could give to his daughter as part of her dowry. When his daughter comes to tell him that her marriage is in trouble, he thinks about taking his wife away from the asylum to hide her existence. He also fantasizes about killing the head doctor, but the vision gets out of hand as a bearded inmate is seen marrying his daughter. The janitor finally dreams of distributing masks to the inmates, providing them with happy faces. He returns to work mopping the floors, no longer able to visit his wife's ward because he lost the keys (picked up by the doctor). He sees the bearded inmate pass by, who bows to him for the first time, as if bowing to his father-in-law.

Cast

| Actor | Role |

|---|---|

| Masao Inoue | the custodian |

| Ayako Iijima | the custodian's daughter |

| Yoshie Nakagawa | the custodian's wife |

| Hiroshi Nemoto | the fiancé |

| Misao Seki | the chief doctor |

| Minoru Takase | patient A |

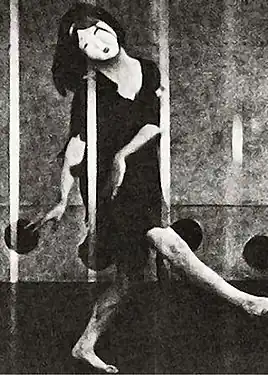

| Eiko Minami | the dancer |

| Kyosuke Takamatsu | patient B, the bearded inmate |

| Tetsu Tsuboi | patient C |

| Shintarō Takiguchi | the gateman's son |

Production

The film is the creation of a group of Japanese avant-garde artists, known as Shinkankakuha (lit. "School of new perceptions" (or sensations)) and is considered the first film of a stillborn "neo-sensationist" current, but shows influences of German expressionist cinema.[11][12] It is one of the early films directed by Kinugasa as well as one of Eiji Tsuburaya's early film works, the latter credited as assistant cinematographer.[13]

Release

Initial release

A Page of Madness was first screened in Tokyo on 10 July 1926.[14] Screenings would have included live narration by a storyteller or benshi as well as musical accompaniment. The famous benshi Musei Tokugawa narrated the film at the Musashinokan theater in Shinjuku in Tokyo.[15] It grossed over a thousand dollars a week, which was impressive at the time considering the price of movie admission was only five cents.[16]

The profits came as a relief to the director, who almost had become bankrupt forming his Kinugasa Motion Picture League,[16] to the point where the film's actors had slept on set or in the office for lack of accommodations and had to help paint sets, make props, and push the camera dolly.[17]

Film scholar Aaron Gerow notes that in a culture that looked down on domestic movie production, A Page of Madness was considered one of the few Japanese films equal to foreign ones;[8] even with that, however, it didn't have much influence on other filmmakers.[8] Unlike some other silent films of the era, A Page of Madness does not feature intertitles.[16] This, coupled with the fact that the surviving print is missing nearly a third of the 1926 version,[16] can make the film difficult to follow for modern viewers.

20th-century screenings and release

The film was thought lost for 45 years, until it was rediscovered by Kinugasa in a rice barrel[18] kept his storage cabin in 1971.[19][20] The rediscovered version lacks a third of the original content.[21]

A music score for the film was composed by Muraoka Minoru in 1971, commissioned by Kinugasa himself.[8]

Two years later, the film was presented at the Rotterdam International Film Festival[22] and the Berlin International Film Festival.[23]

Aonno Jiken Ensemble created a score and debuted it at a midnight screening for the film at the 1998 Seattle Asian American Film Festival.[24] A recording of the accompaniment was released on CD later that year.[25] A documentary featuring the group's rehearsals of the score was created in 2005 and screened at that year's annual Cityvisions festival in New York.[26]

21st-century screenings

The film was shown at the 2004 Melbourne International Film Festival[27] and the 2018 Milwaukee International Film Festival.

Turner Classic Movies aired the George Eastman House Archives print of the film in 2016, using a score by the Alloy Orchestra.[8] Film Preservation Associates and its partner Flicker Alley released a DVD/BR in 2017 with the same score.[8]

The Japanese Avant-Garde and Experimental Film Festival hosted a screening on 24 September 2017 at King's College, London, with a live musical score and an English narration by benshi Tomoko Komura.[28]

CAMERA JAPAN, a yearly Japanese cultural festival based in the Netherlands, featured a screening of the film with live musical accompaniment as part of its 2017 lineup.[29][30] The same year, the film, with a live accompaniment by the Alloy Orchestra, was presented at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival.[31]

The Alloy Orchestra also provided the score for a screening at the Lincoln Center in New York City,[2] and for the aforementioned DVD release of the film.

The film was screened at the 2018 Ebertfest, on 20 April.[32] Four days later, it was screened at the Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, accompanied by a live piano accompaniment.[33]

Benshi Nanako Yamauchi narrated screenings, accompanied by local music group Little Bang Theory, at the Kenilworth 508 Theatre in Milwaukee 8 and 9 October 2022;[34] at the Michigan Theater on 13 October 2022;[35] and at the Detroit Film Theatre on 16 October 2022.[36]

Techno band Coupler was commissioned by the National Museum of Asian Art in Washington, DC to create and perform a new score to accompany the film's screening on 5 May 2023.[37]

The film was screened alongside a fragment of Kinugasa's partially lost 1927 film Oni Azami at the 37th edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, Italy as part of a tribute section celebrating the director's work.[38]

Reception

Modern assessments

Reception of A Page of Madness since its rediscovery has been mostly positive. Dennis Schwartz from Ozus' World Movie Reviews awarded the film a grade A, calling it "a vibrant and unsettling work of great emotional power".[39] Time Out, praised the film, writing "A Page of Madness remains one of the most radical and challenging Japanese movies ever seen here."[40] Panos Kotzathanasis from Asian Movie Pulse.com called it "a masterpiece", praising the film's acting, music, and imagery.[41] Jonathan Crow from Allmovie praised its "eerie, painted sets", lighting, and editing, calling it "a striking exploration of the nature of madness".[42] Nottingham Culture's BBC preview of the film called it, "a balletic musing on our subconscious nightmares, examining dream states in a way that is both beautiful and highly disturbing."[43] Jonathan Rosenbaum of The Chicago Reader praised the film's expressionist style, imagery, and depictions of madness as being "both startling and mesmerizing".[44]

It was included at number 50 in Slant Magazine's "100 Best Horror Movies of All Time", citing the film's visuals and atmosphere as "lingering long after the film ends".[45]

See also

References

- Ragone 2014, p. 192.

- "A Page of Madness". Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Sharp, Jasper (7 March 2002). "Midnight Eye feature: A Page of Madness". Midnight Eye. Archived from the original on 20 April 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- Gerow 2008, p. 42.

- Gerow 2008, p. 12.

- Gardner, William O. (Spring 2004). "New Perceptions: Kinugasa Teinosuke's Films and Japanese Modernism". Cinema Journal. 43 (3): 59–78. doi:10.1353/cj.2004.0017. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Lewinsky, Mariann (1997). Eine Verrückte Seite: Stummfilm und filmische Avantgarde in Japan. Chronos. p. 59. ISBN 3-905312-28-X.

- "A Page of Madness: The Lost, Avant Garde Masterpiece from the Early Days of Japanese Cinema (1926) | Open Culture". Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- Gerow 2008, pp. 26–33.

- Ryfle 1998, p. 44.

- Gardner, William O. (2004). "New Perceptions: Kinugasa Teinosuke's Films and Japanese Modernism". Cinema Journal. 43 (3): 59–78. ISSN 0009-7101. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Heller-Nicholas, Alexandra (15 October 2019). Masks in Horror Cinema: Eyes Without Faces. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-78683-497-3. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Phillips, Alastair; Stringer, Julian (18 December 2007). Japanese Cinema: Texts and Contexts. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-33422-3. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Gerow 2008, p. 116.

- Gerow 2008, p. 45.

- Kotzathanasis, Panos (19 May 2018). "Film Review: A Page of Madness (1926) by Teinosuke Kinugasa". Asian Movie Pulse. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- Joseph L. Anderson and Donald Richie (1982) The Japanese Film: Art and Industry, Princeton University Press

- Bowyer, Justin (2004). The Cinema of Japan & Korea. Wallflower Press. ISBN 978-1-904764-11-3. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- "A Page of Madness". silentfilm.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Gardner, William O. (2004). "New Perceptions: Kinugasa Teinosuke's Films and Japanese Modernism". Cinema Journal. 43 (3): 59–78. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Travers, James (17 April 2016). "Review of the film A Page of Madness (1926)". frenchfilms.org. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- "International Film Festival Rotterdam 1973". MUBI. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- "Berlin International Film Festival 1973". MUBI. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- "No silent treatment — Classic film receives soundtrack from local ensemble". Northwest Asian Weekly. 26 June 2015. Archived from the original on 11 July 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- Aono Jikken - A Page Of Madness, 1998, archived from the original on 11 July 2023, retrieved 11 July 2023

- "Asianamericanfilm: A Page of Madness". asianamericanfilm. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- "Melbourne International Film Festival 2004". MUBI. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- A page of madness Archived 6 June 2023 at the Wayback Machine jaeff.org

- "The complete 2017 programme, A-Z". Camera Japan. 5 October 2017. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- "A Page of Madness (with live soundtrack by Bruno Ferro Xavier da Silva)". Camera Japan. 23 September 2017. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- "A Page of Madness". silentfilm.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- Galassi, Madeline (23 April 2018). "Ebertfest 2018: Nine Things I Learned About A Page of Madness". RogerEbert.com. Roger Ebert Website. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- "A Page of Madness | George Eastman Museum". Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Bickerstaff, Russ (10 October 2022). "Venturesome Japanese Film at the Heart of Theatre Gigante's 'A Page of Madness'". Shepherd Express. Archived from the original on 26 August 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- "A Page of Madness". Michigan & State Theaters. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- Jcden. "The Movie in DFT/DIA "A Page of Madness with Little Bang Theory and Yamauchi Nanako"". jcd-mi.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- "A Page of Madness". National Museum of Asian Art. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- "Teinosuke Kinugasa: From Shadow to Light". Il Cinema Ritrovato. Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- Schwartz, Dennis. "kurutta". Sover.net. Dennis Schwartz. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- "A Page of Madness, directed by Teinosuke Kinugasa". Time Out.com. TR. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- Kotzathanasis, Panos (19 May 2018). "Film Review: A Page of Madness (1926) by Teinosuke Kinugasa By Panos Kotzathanasis". Asian Movie Pulse.com. Panos Kotzathanasis. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- Crow, Johnathan. "A Page of Madness (1926) - Teinosuke Kinugasa". Allmovie.com. Johnathan Crow. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- "BBC - Nottingham Culture - NOW Festival : A Page Of Madness". BBC.com. Nottingham Culture. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- Rosenbaum, Johnathan (26 October 1985). "A Page of Madness". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- "The 100 Best Horror Movies of All Time". SlantMagazine.com. Slant Magazine. 25 October 2019. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

Sources

- Gerow, Aaron (2008). A Page of Madness: Cinema and Modernity in 1920s Japan. Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan. ISBN 978-1-929280-51-3.

- Ragone, August (6 May 2014). Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters (paperback ed.). Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1-4521-3539-7.

- Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan's Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of the Big G. ECW Press. ISBN 1550223488.

External links

- A Page of Madness at AllMovie

- A Page of Madness at IMDb

- A Page of Madness at Rotten Tomatoes

- A Page of Madness at the TCM Movie Database

- A Page of Madness at SilentEra

- A Page of Madness: The Lost, Avant Garde Masterpiece from Early Japanese Cinema (1926) in Film | January 17th, 2019

- Midnight Eye Entry