L'Asino

L'Asino (The Donkey) was an Italian magazine of political satire founded in Rome in 1892, by Guido Podrecca (1865–1923) and Gabriele Galantara (1867–1937), a former mathematics student, designer and cartoonist, both with a socialist background. The two took the pseudonyms "Goliardo" (Podrecca) and "Ratalanga" (Galantara), and with these nicknames signed the outputs of the weekly. The magazine's title was from a saying of Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi that said that "the donkey is like the people: useful, patient and stubborn" (in Italian: "come il popolo è l'asino: utile, paziente e bastonato), which became the subtitle and the motto of the editors.[2][3][4]

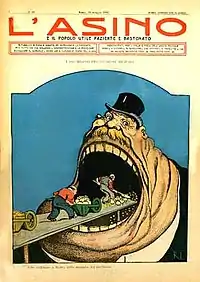

Cover edition May 21, 1905.[1] | |

| Editor | Guido Podrecca and Gabriele Galantara |

|---|---|

| Categories | Satirical magazine |

| Frequency | Weekly |

| Circulation | 100,000 at its peak around 1912 |

| First issue | November 1892 |

| Final issue | 1925 |

| Country | Italy |

| Based in | Rome |

| Language | Italian |

Early years

_a_Bologna_nel_1891.jpg.webp)

_e_Galantara_(Rata_Langa)_per_l'Asino.jpg.webp)

In 1892, Podrecca and Galantara accepted a proposal of the Socialist publisher Luigi Mongini and founded a political satire weekly, L'Asino. The first issue appeared on 27 November 1892. Directed by Podrecca, the periodical gave voice to the demands of the socialist movement and also published informative and ideological articles. It was an immediate success and already by the beginning of 1893, when it began to be printed in colour, it was circulating around 22,000 copies, which rose to 60,000 in 1904 and 100,000 in 1907.[5][6]

LʹAsino was inspired by the great tradition of European political satire from France (La Caricature, Le Charivari, Le Rire and in particular L'Assiette au Beurre to which Galatanra contributed his cartoons) and especially from Germany, with the socialist fortnightly Der Wahre Jacob, to which Podrecca and Galantara drew direct inspiration: double colour covers, texts enriched with drawings and engravings, satire articles alternating with rigorous social criticism.[7]

The magazine immediately focused its attention on the collapse of the Banca Romana in 1893 and Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti.[5] The success of the magazine led its two founders to embark on a daily publication in January 1895, but the experiment was unsuccessful and from August of the same year it reverted to a weekly publication.[2][6] In 1897, Podrecca and Galantara were arrested for subversive propaganda and L'Asino had to suspend publication for a short period.[2]

Anticlericalism

After 1901, the magazine began to criticize the Catholic Church and became the leading anticlerical journal, as a reaction to the anti-liberal campaign by the Vatican against a divorce bill introduced in 1902 and the attempts to set up Catholic trade unions in opposition to the socialist ones.[5] L'Asino launched a virulent offensive against the clergy in terms of customs, morals and religious sentiment, "portraying the image of the lustful, jealous, greedy, corrupt and corrupting priest [...]. With an incessant hammering of cartoons, caricatures, satires, denunciations, easy and often superficial popular articles, Galantara and Podrecca succeeded in widely spreading this image in vast sectors of the popular masses".[2]

As a result, the magazine was banned from Vatican City. The magazine circulated widely among Italian immigrants in the United States. Due to its anticlerical and alleged pornographic content, the papal nuncio in Washington D.C. succeeded to get it banned from entry in 1908. However, the ban was circumvented by printing an American edition in New York City.[8]

As a counterbalance to L'Asino, the Catholic and anti-socialist-inspired satirical magazine Il Mulo (The Mule) was launched in 1907 by Cesare Algranati (editor of L'Avvenire d'Italia).[9]

Rift between the founders

In 1911, the war in Libya caused a serious rift between Podrecca, who had been elected deputy for the Italian Socialist Party in 1909, and supported Leonida Bissolati, who was in favour of the war, while Galantara resolutely opposed in the name of anti-militarist and internationalist principles. L'Asino floundered, giving space to both positions, but the cartoons of Galantara against the war were more effective than the articles of Podrecca in favour of it.[2]

At the outbreak of the World War I there was a momentary rapprochement between the two, when both in the name of sympathy for France sided with the interventionists promoting the entry of Italy in the war devoting many satirical cartoons sneering the enemy's Germany and Austria-Hungary.[6] However, the magazine lost its bite with its nationalist stance.[10]

Galantara contributed to the interventionist cause and war propaganda with his famous caricatures of 'Guglielmone' (Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany) and 'Cecco Beppe' (Franz Joseph I of Austria) and by preaching hostility to 'Teutonic barbarism'. His cartoons were republished in other newspapers in the Entente countries and were exhibited as "Italian Artists and the War" in July 1916 at the Leicester Galleries in London.[2][7]

Not only because of its interventionist choice, but also because of the stance it took towards the Russian revolution (Lenin and the Bolsheviks were portrayed as German agents), L'Asino deviated from the sentiments of many socialists and lost readership.[2]

Cessation and revival

Publication was interrupted from 1918 to 1921, due to technical and economic difficulties, such as lack of paper.[2] Podrecca broke all ties with his socialist past, moving closer to Benito Mussolini and becoming a correspondent for Il Popolo d'Italia. During the war he had shifted to more extreme nationalist positions that led him to interrupt his collaboration with L'Asino and, after the end of the conflict, to be among the first adherents of Fascism. In the November 1919 Italian general election, Podrecca was among the candidates on the list presented by the Fascists in Milan, which was headed by Mussolini and included, among others, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Arturo Toscanini.[6]

Galantara, on the other hand, had returned to his initial socialist principles and resumed the magazine in December 1921. The new series of the weekly, which was printed in Milan at the Avanti! printing house, began with a public act of penitence and a ruthless self-criticism that saved nothing of the choices made over the last twenty years, from 'democratic deceptions' to 'patriotic lies' to 'anticlerical pornography', promising a revitalising return to the rebellious spirit of the origins.[2]

Demise

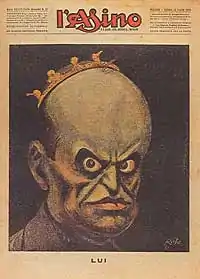

The publication opposed Mussolini's Fascist dictatorship and was forced to suspend publication in the spring of 1925 due to a new law restricting press freedom and after a long series of threats, harassment and interventions of fascist gangs in the newsroom.[2][3] For the cover of the final issue of L'Asino, Galantara made a caricature of Mussolini, entitled Lui (Him) that would become a role model of foreign designers worldwide. Mussolini appeared with a huge bald head and surmounted by a crown on which is written "trouble to anyone who touches me", a huge mouth and two big eyes wide and crossed by a light of madness.[7]

After the closure of L'Asino, Galantara continued to create cartoons for the antifascist satirical newspaper Il Becco Giallo, but on 24 December 1926 he was arrested and taken to Rome's Regina Coeli prison and sentenced to five years of confinement. In early 1927, the sentence was commuted to probation, but he remained barred from any journalistic activity.[2][7]

Trivia

- The Irish novelist James Joyce was an avid reader of L'Asino when he resided in Rome.[4]

L'Asino covers

Cover of 10 April 1904. The Socialist congress in Bologna. A pious wish of the local suckers: to devalue the country while its defenders beat themselves up.

Cover of 10 April 1904. The Socialist congress in Bologna. A pious wish of the local suckers: to devalue the country while its defenders beat themselves up. Cover of 17 March 1907. This is why priests shout against the secular school: the alphabet kills clericalism.

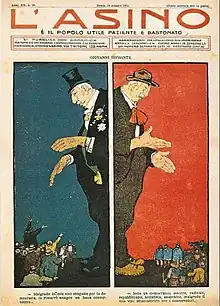

Cover of 17 March 1907. This is why priests shout against the secular school: the alphabet kills clericalism. This cover of 14 May 1911, describes the policy of Giolitti: on the one hand, dressed in elegant suit, he reassures conservatives; on the other, with less elegant clothes, he is addressing the workers.

This cover of 14 May 1911, describes the policy of Giolitti: on the one hand, dressed in elegant suit, he reassures conservatives; on the other, with less elegant clothes, he is addressing the workers. Cover of 30 January 1921 about the XVII Congress of the Italian Socialist Party. The upper part of the cartoon reads: “Lenin: I have finally won! The Italian Socialist Party split...”; the lower part: “Giolitti: The greatest success of my policy! The Italian Socialist Party split..."

Cover of 30 January 1921 about the XVII Congress of the Italian Socialist Party. The upper part of the cartoon reads: “Lenin: I have finally won! The Italian Socialist Party split...”; the lower part: “Giolitti: The greatest success of my policy! The Italian Socialist Party split..."

References

- Archivio immagini (1905), Centro Studi Gabriele Galantara

- (in Italian) Galantara, Gabriele, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 51 (1998)

- (in Italian) L’Asino e Mussolini. Il ventennio del circo, by Emanuela Morganti, Circo, November 2011

- Lernout, Help My Unbelief p. 80.

- Goldstein, The War for the Public Mind pp. 113-14.

- (in Italian) Podrecca, Luigi Guido, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 84 (2015)

- (in Italian) Gabriele Galantara e la satira politica, by Alberto Pellegrino, Centro Studi Gabriele Galantara

- Danky & Wiegand, Print Culture in a Diverse America pp. 24-5.

- (in Italian) 10 settembre 1907. Il giornale "Il Mulo", Bologna Online (Biblioteca Salaborsa)

- Tholas-Disset & Ritzenhoff, Humor, Entertainment, and Popular Culture During World War I p. 49

Sources

- Danky, James Philip & Wiegand Wayne A. (eds.) (1998). Print Culture in a Diverse America, Champaign (IL): University of Illinois Press, ISBN 0-252-02398-6

- Goldstein, Robert Justin (ed.) (2000). The War for the Public Mind: Political Censorship in Nineteenth-century Europe, Westport (CT): Praeger Publishers, ISBN 0-275-96461-2

- Lernout, Geert (2010). Help My Unbelief: James Joyce and Religion, London/New York: Continuum, ISBN 978-1-4411-9474-9

- Tholas-Disset, Clémentine & Ritzenhoff, Karen A. (eds.) (2015). Humor, Entertainment, and Popular Culture During World War I, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-137-44909-2

Further reading

- Mascha, Efharis. Political Satire and Hegemony: A Case of ‘Passive Revolution’ During Mussolini’s Ascendance to Power 1919–1925. Humor (Berlin, Germany) 21, no. 1 (2008): 69–98.

External links

- (in Italian) L'Asino e il popolo: utile, paziente e bastonato, Premio Satira Politica (1982)

- (in Italian) Archivio immagini, Centro Studi Gabriele Galantara