Lobular carcinoma in situ

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) is an incidental microscopic finding with characteristic cellular morphology and multifocal tissue patterns. The condition is a laboratory diagnosis and refers to unusual cells in the lobules of the breast.[1] The lobules and acini of the terminal duct-lobular unit (TDLU), the basic functional unit of the breast, may become distorted and undergo expansion due to the abnormal proliferation of cells comprising the structure.[2] These changes represent a spectrum of atypical epithelial lesions that are broadly referred to as lobular neoplasia (LN).

| Lobular carcinoma in situ | |

|---|---|

_CRUK_166.svg.png.webp) | |

| Diagram showing localized and invasive LCIS |

One subset of LN can be defined as LCIS based on specific cellular traits and tissue changes seen histologically. These lesions are preceded by atypical lobular hyperplasia and may follow a linear progression to invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC), with specific genetic aberrations.[3] This process coincides with the progression of ductal neoplasia to ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive carcinoma. Rarely, terminal ducts may be involved in lobular neoplasia, known as pagetoid spread.

Many do not consider LCIS to be a true case of cancer, but it can indicate an increased risk of future cancer.[4][5][6] In 2018, the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) removed LCIS from tumor staging and considers it a benign entity.[7]

Causes

Genetics

Cells of Lobular Neoplasia (LN), including both Atypical Lobular Hyperplasia and LCIS, and ILC share common genetic alterations, perhaps accounting, in part, for the similarities in histologic appearance. Classic LCIS and invasive lobular lesions are low-grade ER and PR-positive cancers, referring to the positive expression of Estrogen and Progesterone receptors on the neoplastic cells (determined via immunohistochemistry).[8] These entities are also both classically negative for HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2). These hormone and growth factor receptors are clinically significant, as they represent targets for chemotherapy. Chromosomal alterations have also been consistently observed between LCIS and ILC – namely, loss of 16q and gain of 1q, referring to the loss of the long arm (designated q) of chromosome 16 and an extra copy of the long arm of chromosome 1. Furthermore, e-cadherin, the transmembrane protein mediating epithelial cell adhesion, exhibits loss of expression on LN cells, and P120 Catenin exhibits cytoplasmic reactivity.[9] The mechanism for these findings is explained by E-cadherin normally interacting with p120 catenin in the cytoplasm. When e-cadherin is lost, p120 cadherin builds up in the cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells – thus, producing a positive reaction in immunohistochemical testing.[8]

LCIS often have the same genetic alterations (such as loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 16q, the locus for the e-cadherin gene) as the adjacent area of invasive carcinoma.[9] These observations, along with genomic analysis for clonal relationships between the cells of LCIS and ILC, support LCIS as being a precursor to ILC, and that the lesions encompassed by the broader category of Lobular Neoplasia (LN) fall on a linear spectrum of progression. LCIS is often found concurrently with foci of invasive carcinoma and multiple studies have shown, using genetic sequencing techniques, that synchronous LCIS and ILC share clonal cell populations, or originate from the same line of mutated cells.

Diagnosis

Lobular lesions are incidental findings without reliable clinical correlations. Routine mammograms showing suspicious radiologic findings warrant a core needle biopsy in the abnormal area seen radiologically, and may or may not show lobular neoplasia histologically.

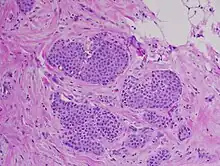

Morphology

Classically, LN, including LCIS, is characterized by enlargement and distension of acini making up the TDLU by proliferation of monomorphic, dyshesive, small, round, or polygonal cells with loss of polarity and inconspicuous cytoplasm. Essentially, groups of round, almost identical looking cells that fill and expand the lobule spaces, occasionally extending into the adjacent terminal ducts – termed Pagetoid extension.[11] Like the cells of atypical lobular hyperplasia and invasive lobular carcinoma, the abnormal cells of LCIS consist of small cells with oval or round nuclei and small nucleoli detached from each other.[12] Mucin-containing signet-ring cells are commonly seen. LCIS generally leaves the underlying architecture intact and recognisable as lobules. Estrogen and progesterone receptors are present and HER2/neu overexpression is absent in most cases of LCIS.[3] Cell borders are indistinct and neither mitotic activity or necrosis are seen. In addition, in situ and invasive lesions exhibit loss of cellular adhesion, considered a characteristic histologic feature, due to the fact that e-cadherin expression is lost (transmembrane protein involved in epithelial cell adhesion).[2] ALH and LCIS are cytologically indistinguishable, so a quantitative threshold is used to classify lesions into either category. A diagnosis of LCIS requires more than half of the acini in an involved lobular unit to be filled with LN cells and the central lumen of the acini should not be visible.[13] Proliferation of LN cells that do not meet these histological characteristics are either Atypical Lobular Hyperplasia or simply lobular distension. Small degrees of cytologic variation can be observed and subsequent subtypes have been described. However, these subtypes have not been shown to be of clinical usefulness and does not have bearing on whether or not LCIS will progress to full invasive carcinoma.[14]

Immunohistochemistry

Lobular Carcinoma In Situ may mimic low grade Ductal Carcinoma In Situ histologically. In these scenarios, pathologists may employ immunohistochemical testing to differentiate between entities.[3] This involves using marked antibodies synthetically developed to bind to target proteins expressed on or inside cells. Specifically, in LCIS, antibodies targeting the e-cadherin protein (or lack thereof) and p120 catenin proteins are used to differentiate LCIS from DCIS. Due to the fact that LCIS shows lack of e-cadherin expression on cell membranes and subsequent p120 catenin buildup in the cytoplasm, lesions that show positive membrane immunoreactivity for e-cadherin are diagnosed as DCIS.[3]

Treatment

Lobular Carcinoma In-situ is both a risk factor and precursor of invasive carcinoma. Furthermore, it is a non-obligate precursor. In other words, LCIS represents a distinct entity in the developmental pathway of cancer that does not guarantee invasive carcinoma. That being said, the historical approach of radical mastectomy (surgical removal of entire breast and axillary lymph nodes) has been substituted by more conservative approaches.[2] Observation is the preferred management option if LCIS is found to occur alone without accompanying infiltrating or invasive carcinoma. LCIS may be treated with close clinical follow-up (frequent scheduled checkups) and mammographic screening, tamoxifen or related hormone controlling drugs to reduce the risk of developing cancer, or, if patients and providers would like a less conservative option, bilateral prophylactic mastectomy.[13] Some surgeons consider bilateral prophylactic mastectomy to be overly aggressive treatment except for certain high-risk cases.[11] This is in part due to the fact that multiple studies have shown no significant different in mortality due to breast cancer between women who underwent surveillance and those who elected for the mastectomy.

When Lobular Neoplasia, or specifically, LCIS, is found on core needle biopsy during routine workups, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends the surgeon perform an excisional biopsy of the region to allow pathologists to rule out concurrent DCIS or invasive cancer. It has been widely reported in the literature that 10-30% of patients with a diagnosis of LCIS on core needle biopsy will receive an upstaged diagnosis after excisional.[13] If LCIS remains the only diagnosis after the excisional biopsy, NCCN guidelines recommend clinical follow-up every 6–12 months with annual diagnostic mammograms.

Prognosis

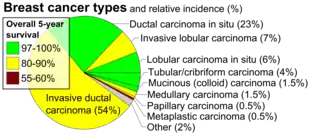

Lobular neoplasia is considered pre-cancerous, and LCIS is an indicator (marker) for increased risk of developing invasive breast cancer in women. This risk extends more than 20 years. Most of the risk relates to subsequent invasive ductal carcinoma rather than to invasive lobular carcinoma.[4]

Older studies have shown that the increased risk of developing invasive cancer is equal for both breasts, and more recent studies suggest that while both breasts are at increased risk of developing invasive cancer, the ipsilateral (same side) breast may be at greater risk.[3] On the other hand, analysis of SEER data (Pooled data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program) revealed the cumulative risk of developing invasive breast cancer after LCIS diagnosis to be 7.1% at 10 years, with equal predisposition in both breasts. The annual risk of developing invasive breast cancer after a diagnosis of LCIS ranges from 1-2%, and the invasive cancers may include intraductal carcinoma as well as intralobular carcinoma, with increased risk of developing invasive ductal.[12] Research regarding the cumulative risk of developing invasive cancer at 5 year intervals varies, with the risk at 10 years being 13—15%, the risk at 20 years being 26-35%, and the risk at 35 years being between 35% and over 50%. The relative risk of developing invasive carcinoma after LCIS diagnosis is 8-10 times greater than in the general population.[2] The overall 5-year survival rate of lobular carcinoma in situ has been estimated to be 97%.[16]

LCIS (lobular neoplasia is considered pre-cancerous) is an indicator (marker) identifying women with an increased risk of developing invasive breast cancer. This risk extends more than 20 years. Most of the risk relates to subsequent invasive ductal carcinoma rather than to invasive lobular carcinoma.[15]

While older studies have shown that the increased risk is equal for both breasts, a more recent study suggests that the ipsilateral (same side) breast may be at greater risk.[17]

Epidemiology

LCIS is identified in 0.5-1.5% of benign breast biopsies. These biopsies are often done in response to suspicious mammographic findings, as discussed in the Diagnosis section of this article. LCIS is identified in 1.8-2.5% of all breast biopsies (including those that show histologic evidence of other Lobular or Ductal Neoplasia.[13] The incidence of LCIS in women without prior history of breast neoplasia has increased from 0.90 per 100,000 persons in 1980 to 3.19 per 100,000 persons in 1998 – but this is likely due to the increased frequency of mammography as a screening tool. This is supported by the fact that the magnitude of increase in frequency of LCIS was greatest among women over 50 years of age (the group most likely to participate in routine mammographic screening).

History

In 1941, a seminal publication by Foote and Stewart introduced the term “Lobular Carcinoma In Situ,” using it to categorize a spectrum of cytologic changes that were precursors to invasive cancer. They described these changes as unrecognizable on gross examination, noninfiltrating, and multifocal, with the cells losing their apical-basal distinction (loss of polarity) and varying in shape but not size.[13] They further predicted that though still contained within the basement membrane, LCIS can indicate an increased risk of future cancer. Researchers and physicians currently treat the diagnosis as a precursor lesion and risk factor for subsequent development of breast cancer.[18]

This article has thus far described Classical LCIS, and there are 2 other variants of LCIS: Pleomorphic LCIS (PLCIS) and Apocrine PLCIS, which may be discussed separately in a separate article.[19]

Unlike ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), LCIS is not associated with calcification, and is typically an incidental finding in a biopsy performed for another reason. LCIS only accounts for about 15% of the in situ (ductal or lobular) breast cancers.[20]

See also

References

- "Lobular Carcinoma in situ (LCIS)". Breast Cancer. Stanford Cancer Center.

- Wen HY, Brogi E (March 2018). "Lobular Carcinoma In Situ". Surgical Pathology Clinics. 11 (1): 123–145. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.09.009. PMC 5841603. PMID 29413653.

- Collins LC (March 2018). "Precursor Lesions of the Low-Grade Breast Neoplasia Pathway". Surgical Pathology Clinics. 11 (1): 177–197. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.09.007. PMID 29413656.

- "Lobular carcinoma in situ: Marker for breast cancer risk". MayoClinic.com.

- "Breast Cancer Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 27 May 2022.

- Afonso N, Bouwman D (August 2008). "Lobular carcinoma in situ". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 17 (4): 312–316. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75e5d. PMID 18562954. S2CID 388045.

- AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Eighth Edition - Part XI - Breast (PDF). The American College of Surgeons. 2018. p. 590.

- Logan GJ, Dabbs DJ, Lucas PC, Jankowitz RC, Brown DD, Clark BZ, et al. (June 2015). "Molecular drivers of lobular carcinoma in situ". Breast Cancer Research. 17: 76. doi:10.1186/s13058-015-0580-5. PMC 4453073. PMID 26041550.

- Canas-Marques R, Schnitt SJ (January 2016). "E-cadherin immunohistochemistry in breast pathology: uses and pitfalls". Histopathology. 68 (1): 57–69. doi:10.1111/his.12869. PMID 26768029. S2CID 19569431.

- Lakhani SR (October 2001). "Molecular genetics of solid tumours: translating research into clinical practice. What we could do now: breast cancer". Molecular Pathology. 54 (5): 281–284. doi:10.1136/mp.54.5.281. PMC 1187082. PMID 11577167.

- Jorns J, Sabel MS, Pang JC (October 2014). "Lobular neoplasia: morphology and management". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 138 (10): 1344–1349. doi:10.5858/arpa.2014-0278-CC. PMID 25268198.

- American Joint Committee on Cancer (2002). AJCC cancer staging handbook : from the AJCC cancer staging manual (6th ed.). New York: Springer. p. 260. ISBN 9780387952703.

- King TA, Reis-Filho JS (July 2014). "Lobular neoplasia". Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America. 23 (3): 487–503. doi:10.1016/j.soc.2014.03.002. PMID 24882347. S2CID 31630480.

- Cotran RS, Kumar V, Fausto N, Robbins SL, Abbas AK (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders. p. 1142. ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8.

- "Breast Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) - National Cancer Institute - Lobular Carcinoma In Situ". Retrieved 2013-01-12.

- Xie ZM, Sun J, Hu ZY, Wu YP, Liu P, Tang J, et al. (September 2017). "Survival outcomes of patients with lobular carcinoma in situ who underwent bilateral mastectomy or partial mastectomy". European Journal of Cancer. 82: 6–15. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2017.05.030. PMID 28646773.

- Page DL, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD, Jensen RA, Plummer WD, Simpson JF (January 2003). "Atypical lobular hyperplasia as a unilateral predictor of breast cancer risk: a retrospective cohort study". Lancet. 361 (9352): 125–129. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12230-1. PMID 12531579. S2CID 6429291.

- "Lobular carcinoma in situ: Marker for breast cancer risk". MayoClinic.com.

- Pieri A, Harvey J, Bundred N (August 2014). "Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast: Can the evidence guide practice?". World Journal of Clinical Oncology. 5 (3): 546–553. doi:10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.546. PMC 4127624. PMID 25114868.

- Page DL, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD, Jensen RA, Plummer WD, Simpson JF (January 2003). "Atypical lobular hyperplasia as a unilateral predictor of breast cancer risk: a retrospective cohort study". Lancet. 361 (9352): 125–129. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12230-1. PMID 12531579. S2CID 6429291.