The Discovery of the Child

The Discovery of the Child is an essay by Italian pedagogist Maria Montessori (1870-1952), published in Italy in 1950, about the origin and features of the Montessori method, a teaching method invented by her and known worldwide.

| |

| Author | Maria Montessori |

|---|---|

| Original title | La scoperta del bambino |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Subject | Pedagogy |

| Genre | essay |

| Published | 1950 |

The book is nothing more than a rewrite of one of her previous books, which was published for the first time in 1909 with the title The method of scientific pedagogy applied to infant education in children's homes. This book was rewritten and republished five times, adding each time the new discoveries and techniques learnt; in particular, it was published in 1909, 1913, 1926, 1935 and 1950. The title was changed only in the last edition (1950), becoming The Discovery of the Child.[1]

The "guidelines"

Maria Montessori, in some parts of the book, carefully explains that what she invented shouldn't be considered a method, but instead some guidelines from which new methods may be developed. Her conclusions, although normally treated as a method, are nothing more than the result of scientific observation of the child and its behavior.

Experience with children with disabilities

As told in the book, her first experiences were in the field of psychiatry, more precisely at the mental hospital of the Sapienza University, where Montessori, at the turn of the and XX century, had worked as a doctor and assistant. During this experience, she took care of intellectually disabled children (in the book they are called with terms that today sound offensive and derogatory, i.e. "retarded children" or "idiotic children", but at that time they did not necessarily have a derogatory connotation). At that time, Italy's Minister of Education Guido Baccelli chose her for the task of teaching courses for teachers on how to teach children with intellectual disabilities (bambini frenastenici). A whole school started later in order to teach these courses, the Scuola magistrale ortofrenica. In this period Montessori not only taught the other educators and directed their work, but she taught herself those "unfortunate" children. As she wrote in the book, this first experience was "my first and true qualification in the field of pedagogy" and, starting from 1898, when she began to devote herself to the education of children with disabilities, she started to realize that such methods had universal scope and they were "more rational" and efficient than those in use at that time at school with normal children.[2]

During this period, she made extensive use and correctly applied the so-called "physiological method", devised by Édouard Séguin for the education of children with intellectual disabilities. It was based on the previous work of the French Jean Marc Gaspard Itard, Séguin's teacher, who, in the years of the French Revolution, worked at an "institute for the deaf and dumb" and also tried to educate a savage called Victor of Aveyron. The physiological method will become the basis of the Montessori method.

Montessori, during her work as assistant at the mental hospital, had the chance to read Séguin and Itard's books, especially the book Traitement moral, hygiène et éducation des idiots et des autres enfants arriérés... (1846). The physiological method devised by Séguin was known and widespread in mental hospitals in the early 20th century, but it was never properly applied. Montessori was also sent to the psychiatric clinics of Paris (Bicêtre) and London for a comparison with the methods applied in schools and on that occasion she noticed that not even abroad the physiological method was properly applied. The book was known and read, but probably it hadn't been understood. The educators, rather than following Séguin, preferred to employ the same methods used in traditional schools.[3]

Montessori realized that the "physiological method" was not just a technique, but also some kind of "spirit". The teacher had to take care of the modulation of the voice, his clothing and even fascinate the "viewer". Such methods were able to "open" the souls of the "unfortunate" children at the psychiatric clinic.

What is called encouragement, comfort, love, respect, are levers of the human soul: and whoever works more in this direction, the more he renews and reinvigorates life around him

Even the development materials used with intellectually disabled children, which derived from the works of Itard and Séguin and which were partly enriched with new ideas by Montessori herself, ended up being effectively adapted for teaching in schools for normal children.

Scientific pedagogy

Montessori started her pedagogical research on children (first retarded and later also normal children) in the early 20th century. At that time, pedagogy was more a philosophical discipline rather than science.

Some pedagogists had already started to think about refounding pedagogy on a scientific basis, and among those was Giuseppe Sergi, one of Montessori's professors. He realized that a renewal of the methods of education and instruction was necessary, adding that "whoever fights for this, fights for human regeneration".

However, Sergi's students had perhaps taken his teachings a little too literally, confusing scientific pedagogy with pedagogical anthropology. In other words, they believed that scientific pedagogy meant just collecting the biometric data of children (such as height, weight, etc.) and studying them in relation to education, looking for factors capable of affecting the physical and mental development of children. This approach, which slavishly employed the methods used in the empirical sciences, was judged by Montessori insufficient for pedagogical purposes.[6]

Prior to Montessori, scientific pedagogy had often been confused with the so-called physiological psychology, whose purpose was just studying the child without even educating him. According to Montessori, the true founder of scientific pedagogy is neither Wilhelm Wundt nor others, but Jean Marc Gaspard Itard, who had developed the first effective method for the education of "retarded children".[7]

Influence on Montessori's thought

Montessory's theory and methods were developed on the basis of the work carried out by previous pedagogists. Undoubtedly, Maria Montessori is credited as the inventory of the method that "freed" the child, released its creativity and that were more effective than the repressive methods then in use. Nevertheless, in the 19th century there had been some forerunners who had come to similar conclusions albeit following a more philosophical approach (for example, the movement of the "New Education", John Dewey and even Lev Tolstoy). In the book The Discovery of the Child, Montessori herself cited the pedagogists and educators who had been a source of inspiration for her. Those are:

- Jean Marc Gaspard Itard (1774-1838);

- Édouard Séguin (1812-1880);

- Giuseppe Sergi (1841-1936);

- Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920).

The first "Children's House"

Montessori began to shift her attention from "retarded children" to the normal ones. Initially she enrolled in the faculty of phylosophy in order to deepen her knowledge in the field of pedagogy. As early as 1907, Montessori had the opportunity to employ her teaching methods directly with normal children. Previously, while working at the mental hospital, she started to realized that this method could also be effectively used on normal children. At the end of 1906, the director of the Istituto dei Beni Stabili di Roma gave her the task of directing the creation of kindergartens in the San Lorenzo (Rome) neighborhood, an area for poors and with degraded living conditions that the Istituto wanted to improve through urban redevelopment and also from a social point of view. Starting in this area kindergartens, which for the occasion were called "Children's Houses" to underline that it was a "school in the house" experiment, was meant for the social elevation of the people. Their social status was low and many of them lived on "casual" jobs or they were unemployed. Ever since that time, the title "Children's House" (Casa dei Bambini) was used by Montessori to denote kindergartens that properly employed the system she had devised.

In the following years and also after the death of Montessori herself, Children's Houses spread in Italy and abroad, also thanks to the intense promotional activity carried out by Montessori itself, through travels, debates and conferences. This favored its spread even in India.

The environment

In her book, Montessori provides some guidelines on how the environment in a Children's House should be, without going into details and leaving a great degree of freedom to teachers. All items that the child interacts with must be "child-friendly", that is, be of a size suitable for children, so that they can be easily used. Sinks, counters, chairs, cupboards and carpets should all be small in size in order to meet the needs of the child.

Furthermore, the environment must be limited, that is, it must contain as many objects as the child can use, no more, no less. An environment that is too small or too poor does not give the child the opportunity to interact with a sufficient number of objects and to learn from them, while an environment that is too large or full of too many objects does not give the child the chance to focus on certain objects for sufficient time to master them. A mistake that is often made is to believe that wealthy children (who therefore live in a richer and larger environment) have more chance to be provided with a better education compared to children who live in a more limited environment.

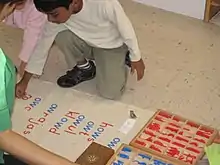

The materials for childhood development

The development materials are nothing more than the set of tools contained in the Children's Houses, and they are aimed at teaching children to do something. The children should never be forced to use them in any way, but it must be a free choice of the child, without any external conditioning. For example, development materials are looms aimed at teaching children to button cloth buttons, or alphabet cards. Maria Montessori developed an extensive set of development materials, partly taking advantage of the previous tools invented by Séguin and Itard and partly developing her own tools. The two above scholars didn't provide particular indications or suggestions on the development materials that should be used in order to teach children to read and write, while Montessori invented some of them.

Montessori also traced some features that the development materials should have:

- isolation of some properties of objects (such as smell, color, temperature etc.);

- containing the solution (the game itself has to make the child understand if the solution is right or wrong - error control);

- aesthetically pleasing;

- able to involve the child in an activity;

- limited.

The method

As told in the book, the school at the time of Montessori had a very strict discipline. The teachers exercised strict control over the children's movements and actions, and this mortified their every spontaneous gesture. One of the pillars of Montessori's teachings is the so-called "active discipline", which essentially consists of "freeing the child", leaving him free to carry out spontaneous actions and repressing only "useless or harmful" actions, such as dangerous actions. for the child or for others, as well as violent or bullying behaviors.

The system of rewards and punishments is also criticized by Montessori; in the first years, she also believed that it was useful for teaching purposes but then she changed her mind. Rewards, and especially punishments, are not only useless, but also harmful, because they put the child on the "false path of vanity". The only engine capable of making the child progress, the only real force capable of lifting mountains, according to Montessori, is the "inner strength", or vocation.

The more words we can save, the more the lesson gets close to perfection.

Children are free to use the development material of their choice and to play with it for as long as they wish but it should be avoided that a child gives the toy to other children or that others take it, as this would put them in competition. In addition, each toy should have a well-defined place and children should take them and put them in place by themselves. When a toy is used by another child, the other kids should wait until it becomes free.[10]

The Children's House and women's emancipation

The book also contains the Inaugural speech delivered on the occasion of the opening of a Children's Home in 1907, a speech that Montessori gave at the ceremony of the opening of the second Children's House in the San Lorenzo (Rome) district. This speech describes the recent history of the San Lorenzo district, its state following the building crisis of the years 1888–1890, and the "admirable" work of restructuring and redevelopment carried out by the Istituto dei Beni Stabili of Rome. In this neighborhood, the first Children's House was established, and Montessori explains the benefits to the community.

One of those advantages is that of women's emancipation, a theme deeply felt by Maria Montessori, who also saw in Children's Houses a way to make it easy for women to work, to become independent and to financially contribute to the needs of the family. The Children's Houses would allow mothers to leave their children in a "school within the house", and that loving environment would definitely reassure them. The Children's Houses should be built close to each house or, if possible, even inside each building.

Montessori's thinking goes even further, predicting that in the future other "problems of feminism that seem insoluble to many" [11] will be solved. In particular, the functions traditionally attributed to women (and in particular to mothers) in the future will perhaps be "socialized" (i.e. provided in common within each condominium); among these even the kitchen, providing a condominium canteen service able to bring the dishes inside each house by lift (as already experimented in the United States). Even the care of the sick could be socialized, considerably alleviating the domestic work of women. Montessori predicted that the presence of an infirmary inside each condominium would effectively isolate a son or husband sick with an infectious disease (such as measles) so as to avoid contagion to other family members more than the mother herself would be able to do, and this would provide benefits in terms of .

The new woman, as a butterfly emerging from the chrysalis, will get rid of all the attributes that once made her desirable for men as a source of material well-being. She will be, like men, a free individual, a social worker and, just like men, she will seek well-being and rest in the renovated and reformed home. She will want to be loved for what she is, and not just as a source of well-being and rest.

— Maria Montessori, Inaugural speech given at the ceremony of the opening of a Children's House in 1907, published in the appendix of the book The Discovery of the Child (1950)[12]

Religion

Inside this book, as well as in other works by Montessori, reference to education and "moral and religious" elevation is quite frequent. Nevertheless, Montessori method is not strictly religious. Inside the book, the feature in which religiosity and the desire to inspire high moral and religious values in the child is perhaps most evident is the choice of an Italian painting to be hung inside each Children's House. The painting chosen by Montessori is the Madonna della Seggiola by Raphael.

Maria Montessori chose this painting for a number of reasons. As told, this painting is supposed to inspire children to religious feelings, even though they are not able to understand the meaning of the painting yet. Furthermore, Montessori chose it also because, if her method spread all over the world, that painting would remind everyone that the school and the Montessori method have Italian roots.

References

- "Dalla pedagogia scientifica alla scoperta del bambino" (in Italian). Retrieved 2019-10-26.

- Pearson2016, p. 29-30

- Pearson2016, p. 33

- Pearson2016, p. 35

- Fabrizio Berloco. "Maria Montessori – The Discovery of the Child".

- Pearson2016, p. 15

- Pearson2016, p. 31

- Pearson2016, p. 84

- "Maria Montessori – The Discovery of the Child".

- Montessori1948, p. 247

- Pearson2016, pp. 115

- Pearson2016, p. 116

Bibliography

- Maria Montessori (1948). The Discovery of The Child. Madras: Kalakshetra.

- Montessori, Maria (2016). La scoperta del bambino (in Italian). Milan-Turin: Pearson Italia. ISBN 978-8839524447.